Kristen Philman first tried methamphetamine in her early 20s, as an alternative to heroin and other opioids. When she discovered she was pregnant, she says, it was a wake-up call, and she did what she needed to do to stop using all those drugs.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Kristen Philman had already been using heroin and prescription painkillers for several years when, one day in 2014, a relative offered her some methamphetamine, a chemical cousin to the stimulant amphetamine.

“I didn’t have any heroin at the time,” says Philman, a resident of Littleton, Colo. “I thought, ‘Oh this might make me feel better.’ “

It did, she says. Soon, she was using both heroin and methamphetamine on a regular basis.

“With heroin I would get sleepy, and then I needed the meth to kind of give me the boost,” she says. “It was a daily thing. I would do heroin and do meth on top of that.”

Then, in December, 2017, after a few months of missed periods, Philman took a home pregnancy test and the result was positive. “I was really scared, because I’d used meth and heroin from the day [my son] was conceived till the day I took the [pregnancy] test,” she says.

Philman is among thousands of women around the United States who used the stimulants methamphetamine or prescription amphetamines during their pregnancy in recent years, researchers say. While the trend has garnered little media attention, physicians in some regions have been struggling to tackle the problem and the impact of the drug on the women and infants.

Philman entered recovery once she was pregnant, and was put on methadone for her opiate use. She says her OB-GYN was candid with her about the potential effects of her meth use on the fetus — including premature birth and death.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Since there are no medications to treat methamphetamine use disorder, some providers have had to improvise their approaches to treating these women, while many others remain unaware of the problem and how to deal with it.

A study published Thursday in the American Journal of Public Health confirms the rise in meth use among pregnant women and provides new data illustrating the scope of the problem. The research, which analyzed hospital discharge records between 2004 and 2015, found that as opioid use among pregnant women has grown in recent years, so has their use of amphetamines, and particularly methamphetamine.

Though that class of drugs includes prescription medicines like Adderall and Dexedrine that are sometimes used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, “we think our findings nearly entirely represent illicit methamphetamine use,” says Dr. Lindsay Admon, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan and the lead author of the study.

The rise in amphetamine use began after 2008-2009, the study found. By 2015, however, tens of thousands of pregnant women were on the drugs.

“In total, we identified 82,000 deliveries that were affected by amphetamine use disorders,” says Admon.

According to the study, the increased rates of amphetamine use grew disproportionately in three regions of the U.S. — the South, the Midwest and the West. Rural areas had higher rates than cities, with the rural West having the highest rate of all regions. Opioid use among pregnant women on the other hand, was highest — 3 percent of all delivery hospitalizations — in rural northeastern United States.

“By 2014-2015, amphetamine use disorder was identified among approximately one percent of all deliveries in rural western United States,” says Admon. And that’s higher than the prevalence of opioid use among pregnant women in most regions in the country.

Health effects on mom and baby

Long term methamphetamine use during pregnancy has serious health risks for the mother, Admon says. It increase a woman’s risk of dying during or after childbirth or of having lifelong health complications — “things like blood transfusion, heart failure, cardiac arrest,” she says. “And then eclampsia — which is the most severe form of preeclampsia — where a woman has a seizure.”

“That’s something we’re seeing here,” says Dr. Tricia E. Wright, an OB-GYN and associate professor at the University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine. Wright has been treating pregnant women with methamphetamine use for many years.

The increased risk for preeclampsia signals an increased risk of heart attacks and stroke for the mother later on in life, she adds.

If the mother keeps using the drug through the pregnancy and doesn’t get prenatal care early on, the consequences can sometimes be fatal.

“I had a recent maternal death from methamphetamine use,” says Wright.

The woman was 28 weeks pregnant, “had a very bad heart disease” and did not receive any prenatal care, Wright says.

“She had a heart attack at home while using drugs,” Wright says. The woman’s boyfriend gave her chest compressions and rushed her to the emergency room, where doctors did an emergency C-section and put her on life support. But neither the mother or the baby survived.

The new study found that methamphetamine and prescription amphetamines, pose some risks to the infant, too.

It increases the risk of premature birth. It also increases the chances of having a condition called placental abruption, which cuts off oxygen supply to the fetus and causes heavy bleeding in the mom.

The new study is an important one, says Wright. “It shows with all the focus on opioids in this country, we can’t forget the other drugs — especially methamphetamine.”

National attention tended to turn away from methamphetamine in the late 2000s, because meth use was thought to be on the decline, says Dr. Mishka Terplan, an OB-GYN and an addiction specialist at Virginia Commonwealth University. But healthcare providers working in rural areas in certain regions of the country never really saw the drugs go away, he says.

“And many have been noting an increase in amphetamine and methamphetamine use in general, as well as amongst pregnant women,” adds Terplan.

Challenges of treating amphetamine use in pregnancy

“Over half of our patients that are being treated for opioid use disorders also have stimulant use disorders — meaning that they’re taking methamphetamine regularly,” says Dr. Amanda Risser, a family medicine physician at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who runs a program called Project Nurture for pregnant women with substance use disorders.

Amanda Risser runs a program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Ore., for pregnant women with substance abuse problems. There are currently no medications to treat methamphetamine addiction, she says, and residential treatment is often the best option for patients.

Beth Nakamura for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Beth Nakamura for NPR

“Since we started doing this work in 2014, we’ve always cared for women who have a tendency to use meth along with the opiates that they’ve been using,” Risser says.

Her colleagues at clinics in rural Oregon have observed the same trend there, too, she says.

Most patients want to stop using drugs when pregnant, says Risser, but quitting amphetamines is difficult.

The lows experienced with withdrawal from methamphetamine is strong, she says. The women feel depressed, unhappy and ill at ease. That’s because long term use of meth “can cause significant decreases in neurotransmitters responsible for people’s wellbeing and happiness.”

And unlike with opioids, there is no medication to help patients with methamphetamine withdrawal. So, despite their best intentions, some of Risser’s patients continue using methamphetamines even as they start their methadone treatment for opioid use.

The best treatment option for such patients is “time and support,” says Risser. Her clinic also provides behavioral therapy to help patients stay off of methamphetamine.

The project also provides residential treatment, which allows the women, many of whom are homeless, to get off the streets and be somewhere safe during the pregnancy — as well as after the birth of their child.

“Access to high quality residential treatment is very important,” says Wright.

Having a supportive OB-GYN made all the difference to Philman’s pregnancy. When she learned she was pregnant, she rushed to the Denver Recovery Group, where she was put on methadone for her opiate use. She found an OB-GYN who was supportive and understanding about her drug use, Philman says, while being candid with her about the potential effects of methamphetamine use on the baby.

“I was scared that something would be physically wrong with my son,” Philman remembers.

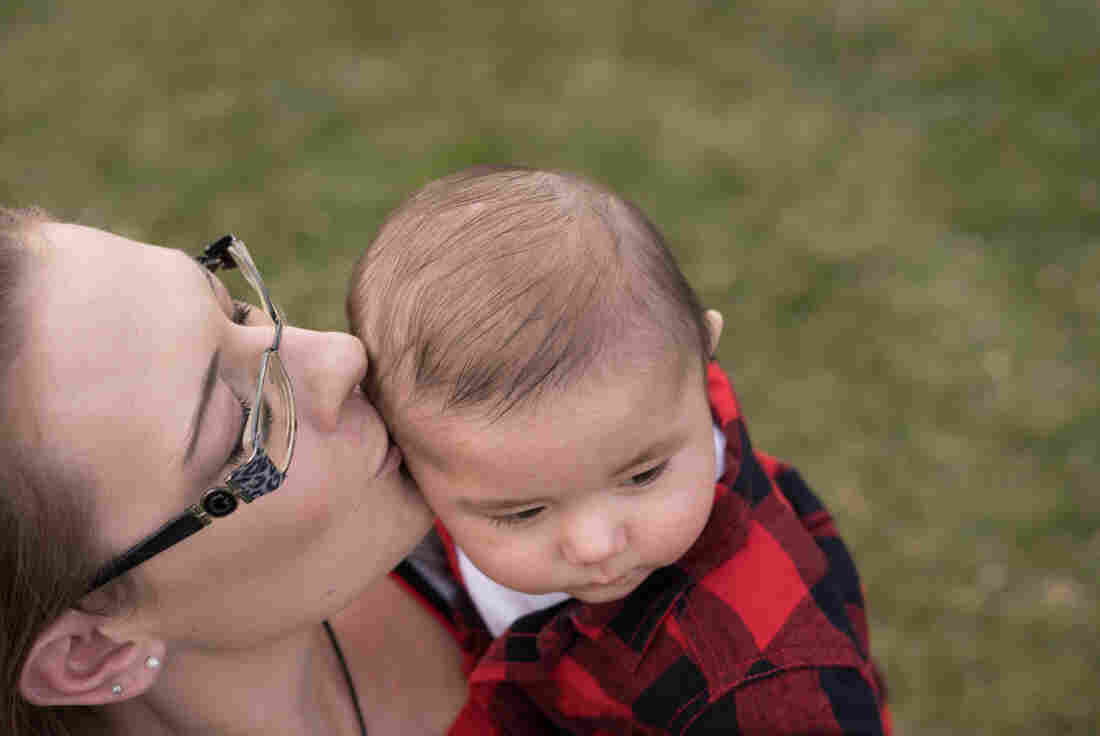

Philman holds her six-month old son, who was born healthy.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

That fear and worry over her son’s health, and the support from her physician, her parents and her Denver Recovery Group counselor are what helped her get through methamphetamine withdrawal, she says. What also helped, she says, was that her partner had also stopped using drugs and was well on his way to recovery.

Still, the first month of treatment during her pregnancy was difficult, she says, and she briefly returned to using meth a couple of times. But after that, she stayed clean.

The monthly ultrasounds were a big motivator, she says. “Just seeing my son grow was kind of a reality check.”

The lingering stigma of addiction

Still, many pregnant women aren’t as lucky as Philman in finding supportive doctors or nurses.

When Andrea Rano, a resident of Portland, became pregnant in 2016, she was living in a friend’s garage with her then-boyfriend. Both of them were using opioids and methamphetamine. Over the next few months, Rano worried about her pregnancy and felt guilty and ashamed about her addiction. Those feelings just fueled her drug use, she says, and kept her from seeking care.

When she did go to a hospital for a dose of methadone, the nurse practitioner she met with was disparaging and insisted on doing a urine test for drugs, Rano says, and threatened to report her to the authorities.

“I ended up leaving that hospital and feeling really uncomfortable about doctors and healthcare after that,” she says,, starting to cry. “It was really hard to be in that situation — to want to get help and feel like it was impossible.”

She felt scared, ashamed and helpless. “All I could think about was, what am I going to do? How am I going to help? Is there any help out there for me? And even if I get help, will it matter? Because what if they take my child away anyway?”

That’s the situation many pregnant women like Rano find themselves in, says Dr. Curtis Lowery, the chairman of the OB-GYN department at the University of Arkansas for the Medical Sciences, in Little Rock, Ark. Most physicians share our society’s stigma around drug abuse, Lowery says, adding that medical education doesn’t teach physicians about substance use disorders or about how to treat these conditions.

“It’s not something that most OB-GYN residencies or family medicine training expose their residents to,” says Lowery.

But that stigma can end up endangering these women’s lives and their babies.

“The worst thing we can do to pregnant women is to vilify them as a result of any kind of drug use,” Lowery says. “All you’re going to do is drive them underground.”

What these women really need is good prenatal care and help staying away from drugs, he says. “One of the things you don’t want to do with meth addiction is delay treatment,” says Lowery. “The faster you can get the patient off the drug, the better it is for the fetus and the mother.”

And that’s the little piece of good news — that with the right kind of help, women can recover from their dependence on the drug and go on to have normal pregnancies.

“We know that getting them screened, getting them into treatment early, getting them to stop using it at any point during the pregnancy — they have better outcomes and actually, normal outcomes,” says Wright. And “the longer they can remain abstinent from the drug, the more chance they have at recovery.”

Philman hasn’t used methamphetamine or opioids for almost a year. She’s going back to finish her degree — enrolled in college classes that will start in January.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

That’s been the happy experience of Philman and her son, who was born full-term and is a healthy 6-month-old now. His mom has been off the drugs for almost a year now, and is already enrolled to return to college in January.

While Rano wasn’t as fortunate initially, someone finally told her about Project Nurture in the seventh month of her pregnancy.

She was living out of a car at the time, along with her boyfriend and their dog. He was still using drugs. Rano was getting methadone for her opioid use, but was having a hard time staying off of meth.

With the support she eventually got from Risser, along with residential treatment at Project Nurture, and support from her counselor, doula and other women getting treated at the program, Rano was able to turn a corner.

She was able to stay off methamphetamine through the remainder of her pregnancy. Her son was born three weeks early — but he was and is healthy.

“It was the most amazing thing ever,” says Rano. “He was just so beautiful.I was just so happy that I was able to be there and do that — and that he was there, and he was fine.”

She credits her recovery and her son’s health to Project Nurture. “I got a huge support network [there],” she says. “I got a doctor who was absolutely amazing. I got in-patient treatment, which was having somewhere to live, somewhere to take my child home after I gave birth. It totally turned my life around.”