Greg Kelly at home in Delphia, Ky. A former coal miner, Kelly has an advanced stage of black lung disease known as complicated black lung or progressive massive fibrosis.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

Greg Kelly’s grandson, Caden, scampers to the tree-shaded creek behind his grandfather’s house to catch crawdads, as Kelly shuffles along, trying to keep up. Kelly’s small day pack holds an oxygen tank with a clear tube clipped to his nose. He has chairs spaced out on the short route so he can stop every few minutes, sit down and catch his breath, until he has enough wind and strength to start out again for the creek.

“I just pray that the Lord give me as much time as I can with him,” Kelly said, his eyes welling with tears. “He just lightens my life. I want to be as fun with him as I can. And do as much as I can with him.”

Caden is 9 years old, and even at his age he knows what happened to his paw-paw at the Harlan County, Ky., coal mines where Kelly labored as a roof bolter for 31 years.

“That coal mine made your lungs dirty, didn’t it?'” Kelly recalled Caden asking. “Yeah it did. … And I can’t breathe and I have to have my backpack to breathe,” Kelly told him.

Former coal miner Danny Smith and his family used to ride their ATVs and go camping on this reclaimed strip mining site in Pike County, Ky. But Smith is no longer able to do such things because of his advanced black lung disease.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

It’s a familiar tale across Appalachia. Two hours north and east, beyond twisting mountain roads, Danny Smith revved up a lawn mower. He wore jeans, a T-shirt and a white face mask stretching from eyes to chin, and he pushed only about 15 feet before he suddenly shut off the mower, bent to his knees and started hacking uncontrollably.

“Oh God,” he gasped, as he spit up a crusty black substance with gray streaks, and then stared at the dead lung tissue staining the grass. Still coughing and breathing hard, Smith settled into a chair on his porch and clipped an oxygen tube to his nose.

After spending just 12 years underground, his lungs are so bad he faces what coal miners decades older and with decades more in mining have endured. His lung tissue is dying so fast, his respiratory therapist says, it just peels away.

“I’m terrified,” Smith said, as he remembered his father’s suffering when he was struggling with the same coal miner’s disease.

“I sure don’t want to go through what he went through. I seen a lot of guys that died of black lung and they all suffered like that.”

Kelly says he used to wrestle with his grandson before he was diagnosed with black lung disease. Fishing is one of the few activities he is still able to do.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

A multiyear investigation by NPR and the PBS program Frontline found that Smith and Kelly are part of a tragic and recently discovered outbreak of the advanced stage of black lung disease, known as complicated black lung or progressive massive fibrosis.

A federal monitoring program reported just 99 cases of advanced black lung disease nationwide from 2011-2016. But NPR identified more than 2,000 coal miners suffering from the disease in the same time frame, and in just five Appalachian states.

And now, an NPR/Frontline analysis of federal regulatory data — decades of information recorded by dust-collection monitors placed where coal miners work — has revealed a tragic failure to recognize and respond to clear signs of danger.

For decades, government regulators had evidence of excessive and toxic mine dust exposures, the kind that can cause PMF, as they were happening. They knew that miners like Kelly and Smith were likely to become sick and die. They were urged to take specific and direct action to stop it. But they didn’t.

“We failed,” said Celeste Monforton, a former mine safety regulator in the Clinton administration who reviewed the NPR/Frontline findings.

Kelly and his wife, Lisa, say grace before Sunday dinner.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

“Had we taken action at that time, I really believe that we would not be seeing the disease we’re seeing now,” said Monforton, now a workplace safety advocate who teaches at George Washington and Texas State universities.

“Having miners die at such young ages from exposures that happened 20 years ago … I mean this is such a gross and frank example of regulatory failure.”

It’s an “epidemic” and “clearly one of the worst industrial medicine disasters that’s ever been described,” said Scott Laney, an epidemiologist at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

“We’re counting thousands of cases,” he said. “Thousands and thousands and thousands of black lung cases. Thousands of cases of the most severe form of black lung. And we’re not done counting yet.”

“They’re essentially suffocating while alive”

This advanced stage of black lung leaves lungs crusty and useless, says Dr. Robert Cohen, a pulmonologist at the University of Illinois, Chicago who has spent decades studying black lung and PMF disease.

“You have a much harder time breathing so that you can’t exercise,” Cohen noted. “Then you can’t do some simple activities. Then you can barely breathe just sitting still. And then you require oxygen. And then even the oxygen isn’t enough. And so … they’re essentially suffocating while alive.”

“There’s a lot of memories here, some good, some bad,” says Smith, while reflecting on his years working at the now defunct Solid Energy mine in Pike County.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

The toxic mine dust that causes severe disease isn’t coal dust alone. It includes silica, which is generated when miners cut sandstone as they mine coal. Many coal seams in central Appalachia are embedded in sandstone that contains quartz. And when quartz is cut by mining machines, it creates fine and barbed particles of silica dust — fine enough to be easily inhaled and sharp enough to lodge in lungs forever.

In the past 30 years, the biggest coal seams were mined out in Appalachia, leaving thinner seams coursing through sandstone.

“All the good seams were gone because there were hardly no solid seams of coal left,” the 54-year-old Kelly remembered. “And there [was] more rock in the coal.”

The silica dust that resulted from cutting that rock was far more dangerous than coal dust alone.

Silica is “somewhere around 20 times more toxic and can cause disease much more rapidly,” said Laney.

The NPR/Frontline investigation found thousands of instances in which miners were exposed — not just to coal dust but to dangerous levels of toxic silica dust. The federal Mine Safety and Health Administration’s own data chronicle 21,000 instances of excessive exposure to silica since 1986.

At the same time, NPR identified black lung diagnoses involving miners in their 30s who also experienced rapid progression to the advanced stage of PMF. Smith says he was diagnosed with PMF at 39. NIOSH has confirmed this trend in its studies.

“We’ve got the bodies to prove it”

NPR/Frontline analyzed 30 years of data collected by federal regulators. They measure coal and silica dust where miners are working, and in 85 percent of the samples collected silica was at safe levels. But for that other 15 percent — which amounts to 21,000 dust samples — the data show that miners were exposed to excessive silica levels that violated federal health standards.

“That’s what causes disease, is the excessive exposure,” said Jim Weeks, an industrial hygienist and mine dust specialist at MSHA in the Obama administration and at the United Mine Workers union before that.

An NPR review of mine dust regulations also found that federal enforcement does not directly address silica dust. If regulators measure too much silica in mine air, they place coal mines on much tougher limits for coal dust. That’s supposed to lower the silica exposure because coal and silica dust are often mixed.

But our investigation found that this indirect approach to controlling silica dust didn’t always work. MSHA’s 30 years’ dust sampling data show dangerous levels of silica or quartz where miners were working close to 9,000 times, even after coal mines were required to meet reduced limits for coal mine dust.

“They didn’t pay sufficient attention,” Weeks concludes. “And …we’ve got the bodies to prove it. I mean these guys wouldn’t be dying if people had been paying attention to quartz. It’s that simple.”

A coal processing plant sits abandoned near Smith’s home in Pike County.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

We found another example of overexposure in MSHA’s data. Each time federal mine inspectors issued citations for too much silica, which they did only a fraction of the time, they included an estimate of how many miners were affected. A review of those data shows more than 9,000 workers were exposed to silica levels that the regulations considered dangerous.

This excessive exposure to silica almost certainly happens more often than the data suggest. That’s because the data show only what happens when regulators are checking. The inspectors don’t check most of the time miners are working. Dust sampling takes place during regular mine inspections, which are scheduled four times a year in underground mines and twice a year at surface operations.

And until recently, sampling did not take place every hour miners worked or while mines were at full production.

Another finding of the NPR/Frontline investigation: During some of the heaviest periods of exposure to silica, regulations allow miners to work without any monitoring for it at all.

A white rock dust

Smith drove us past a pair of adjacent coal mines near his home in Canada, Ky., where he and other miners cut nothing but rock for months.

He was reluctant to pull over at the Rockhouse Energy Mine, even though it is closed, because security guards were watching from a parking lot. So he slowly passed by, describing work shifts that lasted 16 hours a day, seven days a week, for months, while cutting through solid rock. They used drills and mining machines to dig from one coal seam to another underground.

“It wasn’t coal dust that you would see,” Smith said. “It was more of a white rock … dust.”

Smith and his coworkers were cutting what’s called a slope mine. It’s not really mining because there’s no coal involved. It’s all about cutting through mountainsides or blocks of rock to reach coal seams.

And because there’s no coal, it is considered development mining or construction. So sampling the air for toxic dust is not required, even though it is the most dangerous dust. Former MSHA officials told us some inspectors did it, but most did not.

Smith spent months cutting at least two slope mines in his career and believes that could explain his severe disease, even though he worked underground only 12 years.

An old photograph of Kelly taken when he was 19 captures him taking a break after working in the mines.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

“Very possible,” he said, as we passed the mine’s abandoned conveyor belts that stretch over the road. “Most of my mining career I run a continuous miner. I run a roof bolter also. And it’s very possible from all the hours we worked.”

Roof bolters operate a machine that pins roof supports into underground mines by drilling into solid rock. The machines have customized dust-control systems that suck away dust, but miners complain they get bursts of silica dust when they begin drilling and then later when they empty boxes that collect the dust that was sucked away during drilling.

The machine known as a continuous miner grinds up rock and coal. Dust is supposed to be controlled by massive ventilation fans that pump air through the mine, while heavy curtains channel that air to sweep away dust. Mining machines spray water as they cut, to tamp down dust.

NPR interviewed 34 coal miners, all diagnosed with PMF and with 12 to 40 years in mining in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Virginia and Kentucky. Sometimes the dust controls worked, most told us, and sometimes they didn’t.

Federal law requires mining companies to offer dust masks or respirators to miners, but their use is not required. The law considers them a secondary and optional means of protection. Mines are required to provide air clear of dangerous dust, first and foremost.

Most of the sick and dying miners we interviewed who used dust masks said they often didn’t work.

“They would clog up with dust, sweat and spit,” said Edward Wayne Brown, who spent 21 years underground in Buchanan County, Va. “And then it feels like somebody just sitting there with their hand over your face.”

In fact, dozens of miners, including Smith, have filed product liability lawsuits against dust mask suppliers. Most cases are still pending but a few have resulted in multimillion-dollar verdicts for the miners.

“This is probably the oldest known occupational hazard,” said retired industrial hygienist Weeks, who has a collection of antique books to prove it — with references to mine dust hazards from Pliny the Elder in the first century and another dating to the 15th century.

“There’s nothing new about this,” Weeks added. “And you’d think by now we’d have figured out how to deal with it.”

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here

Awareness of silica dust as a hazard in the United States goes back at least 100 years, with a series of studies and reports beginning in 1908. In the 1930s, hundreds of workers were sickened and killed by exposure to silica dust while tunneling through a mountain of solid rock in West Virginia.

In 1974, NIOSH first called for silica exposure limits twice as strict as those in place for coal miners and other workers. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that MSHA and others began to get serious about silica in coal mines.

NPR and Frontline obtained internal memos from the Clinton administration that showed alarm back then about clusters of advanced lung disease among coal miners as young as 40. MSHA sent out alerts to coal mining companies, warning about excessive exposure to silica dust and severe disease among miners. NIOSH again called for a silica exposure limit that would be twice as tough, plus separate regulation of silica, as did a Department of Labor advisory committee.

“We started a national campaign first to raise awareness,” recalled Davitt McAteer, the assistant secretary of labor for mine safety and health from 1994 to 2000.

“And it was that campaign that began to try to go after the silica requirements, raise the silica standard, and start on a separate path to control silica.”

McAteer proposed a major overhaul of the dust sampling system, which included other loopholes that permitted excessive exposures and inaccurate measurement of coal mine dust. But the effort encountered stiff opposition from the National Mining Association, the industry’s biggest lobbying group. The group sued over some elements of the plan and won.

“And then we ran out of time,” McAteer says. “And it’s something that’s unfortunate and put a lot of lives at risk.”

Mine dust loopholes

The regulation of silica dust wasn’t addressed during the administration of George W. Bush. During the Obama administration, mine safety advocate Joe Main was in charge of MSHA. Main was the longtime health and safety director at the mineworkers union and was on that Labor Department advisory committee that sought tougher regulation of silica back in 1996.

“It was very obvious that that whole scheme that had been in place, that has left so many people sick, had to be changed and had to be fixed,” Main said.

He was successful in closing major mine dust loopholes, and he deployed new technology — dust sampling devices that measured coal dust in real time and helped make sampling more immediate, honest and accurate.

Main also made the exposure limit for coal mine dust tougher. But not the exposure limit for silica. He didn’t include any specific action on silica in his plan.

“A high tide rises all boats, as the saying goes,” Main explained. “We were going to get a benefit out of reducing overall dust exposure by what we did. [That] would not only lower coal mine dust but all dust that was part of that, including silica.”

But as the NPR/Frontline data analysis shows, that formula failed thousands of times in the past. Lowering overall mine dust doesn’t necessarily reduce silica exposure to safe levels.

Smith worked mostly for Sidney Coal Co. during his 12 years as an underground miner. Sidney was owned by Massey Energy, a defunct coal giant with multiple mine disasters in its history and a CEO who went to federal prison for conspiracy to violate mine safety laws.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

Monforton wonders why MSHA missed or ignored that part of the dust sampling data.

“The fact that [NPR and Frontline] went back for 30 years and looked at that data, and that data was available to the agency to assess as well, why wasn’t that problem recognized and rectified?” Monforton asked.

Main and other former MSHA officials say they thought they were doing what they needed to do to control silica.

Another agency did act on silica during the Obama administration. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration concluded a 44-year review of silica exposure by enacting tougher regulation of silica dust.

So now, every industry in the country that cuts rock, every industry except mining, has separate regulation of silica and an exposure limit twice as tough — the limit first recommended by NIOSH in 1974.

Mining companies also knew they were cutting more quartz, creating more silica dust, and exposing miners to toxic dust. They were not only clearly warned by MSHA in the 1990s; they could see what was going on in their mines. Cutting rock slows mining machines and hurts production. And rock has to be removed from coal before it can be sold.

So NPR and Frontline wanted to know why mining companies didn’t act on their own to protect their workers.

“Sure they could have done that,” responded Bruce Watzman, the National Mining Association’s top lobbyist for more than 30 years. “But … I’m not going to speculate on why they did or didn’t do what they chose.”

“Our focus here is forward looking,” he said. “How do we prevent this in the future? I can’t answer for … what happened in the past.”

Watzman also asserted that the industry “is doing far better today than we did in the past, far better.”

That assessment is based on new data from MSHA following the new coal mine dust rules that began to take effect in 2014. Since then, mining companies have met exposure limits for coal and silica dust 99 percent of the time, the data show.

MSHA cited the same data in a written statement to NPR and Frontline.

“The dust rule … has greatly reduced miners’ exposure to respirable dust,” wrote MSHA spokeswoman Amy Louviere, who also noted a sharp drop in the past 10 years in the percentage of mine dust samples with excess silica. Her statement did not address the NPR/Frontline findings showing 30 years of excessive exposure to silica.

“MSHA continues to work diligently to protect coal miners’ health,” Louviere said.

But NIOSH epidemiologist Laney isn’t convinced the problem is solved.

“They’re sampled very infrequently so we don’t know what’s going on with these miners when they’re not being sampled,” Laney said. “Ninety-nine percent of the time we don’t have information on that.”

That’s also the conclusion of a recent review by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The new coal dust rules, the review committee said, “may not guarantee that exposures will be controlled adequately or that future disease rates will decline.”

It will also take 10 years or more to know whether the new dust rules result in fewer cases of disease. It takes that long for disease to develop.

“I said I suspect silica. I didn’t say it was”

MSHA declined multiple requests for interviews with top agency officials, including David Zatezalo, a former coal company executive and industry lobbyist who now heads the agency.

So we showed up at West Virginia University in September where Zatezalo was scheduled to make a rare public appearance.

“You hear the phrase in health circles of progressive massive fibrosis, these sorts of things,” Zatezalo told an audience of mining engineering students, agency employees and industry executives and lobbyists.

“To me, I believe those are all clearly silica problems,” Zatezalo continued. “Silica is something that has to be controlled.”

But immediately after his speech, when NPR and Frontline approached him, Zatezalo seemed suddenly uncertain about silica and PMF.

“I don’t think that the science of the causation is that well-defined,” Zatezalo said.

Asked about the direct link between silica and disease he described in his speech, Zatezalo became defensive.

“No, I said I suspect silica. I didn’t say it was. … I think until such time as you figure out what it is you don’t really know,” Zatezalo responded.

So far, under Zatezalo, MSHA has no plan to address a tougher limit for silica dust or separate regulation of silica in coal mines.

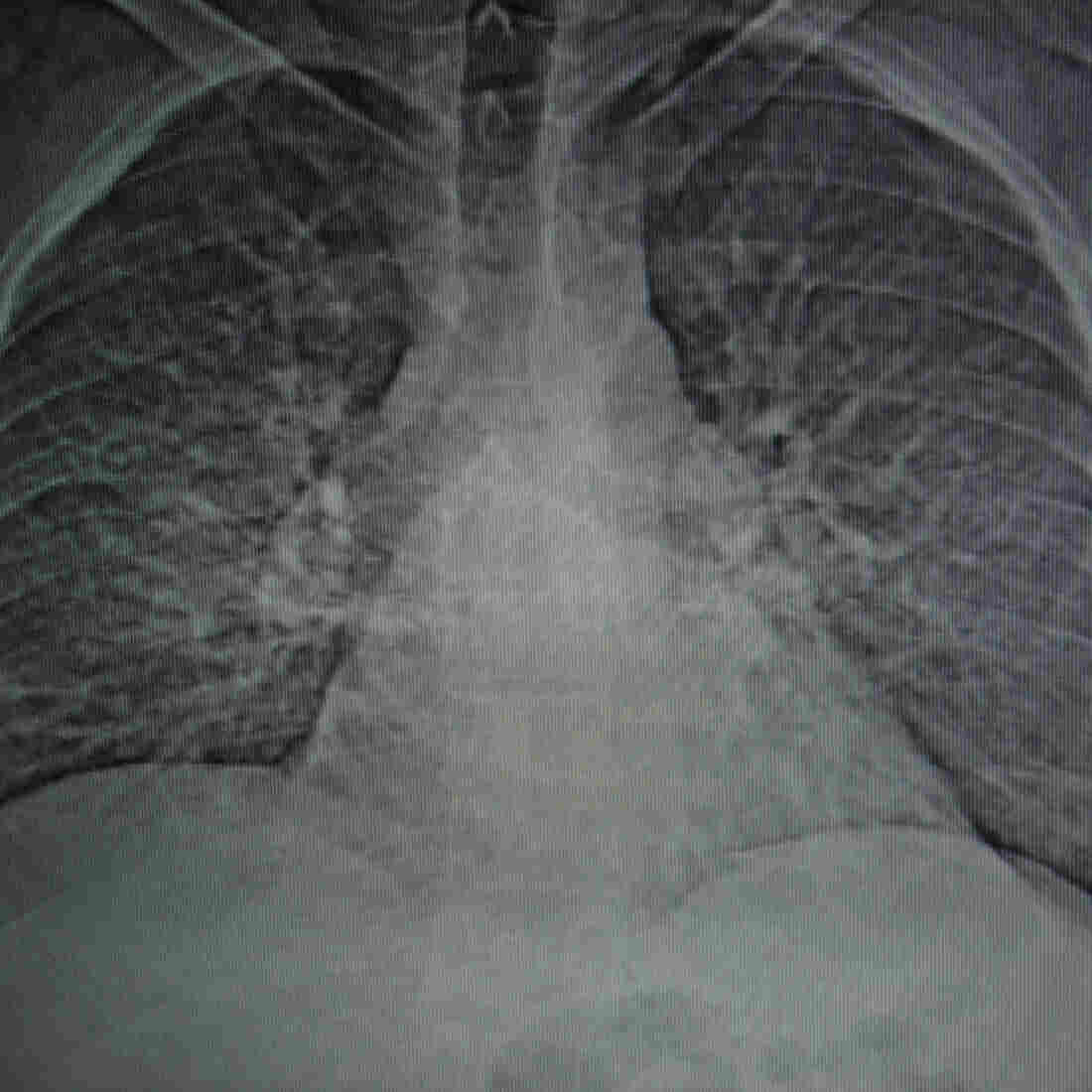

A CT scan shows the damage to Smith’s lungs caused by progressive massive fibrosis.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

In the meantime, the PMF epidemic continues. The biggest cluster of disease ever reported, according to NIOSH, continues to build at the Stone Mountain Health Services black lung clinics in Southwestern Virginia. The clinics continue to diagnose new cases at the rate of about a dozen a month.

“I’m not seeing any slowdown whatsoever,” says Ron Carson, who directed the Stone Mountain clinics for 28 years before retiring earlier this year.

“I think that America needs to know that these miners … have paid a price,” Carson added, his voice breaking. Carson cited the nation’s decades of dependence on coal for power and steel production.

“They paid a price so that we can have luxury and … so many have died. Thousands have died.”

“Every one of us is either crippled or dead”

Kelly has a long list of simple tasks he can no longer accomplish: walking up his driveway to the mailbox; climbing the few steps to his barn; riding horses; even just getting up to head to the bathroom. He has to stop and rest on the way, he says.

But what hurts the most are the things he can’t do with his grandson, Caden, especially playful wrestling on the floor.

“Now he has to wrestle a pillow while I call the match,” Kelly said, his voice halting and his eyes red. “It’s still fun, but …” and Kelly paused, his face tight and the tears flowing.

“I want to be that pillow.”

Incomplete projects are sprinkled around Kelly’s home. Kelly has a long list of simple tasks he can no longer accomplish; even just walking to the mailbox is difficult.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

Smith pulled up to another mine, which was also closed but had no guards in its weed-choked parking lot. This Solid Energy mine, along with the Rockhouse mine he drove by earlier, was operated by Massey Energy, now a defunct company with deadly mine disasters in its history and a CEO who went to prison for conspiracy to violate mine safety laws.

Smith got out and walked up to a rusted fence with a padlock. A ball cap shaded his face. Sunglasses hid his tears.

“It’s [been] eating at me for the last two years,” he said, “that I’m going to die over this. … Of all the things that could’ve killed me while I did work there, the rockfalls and all that stuff, I lived through all of that. And I find out years later I’m going to die over black lung. And it’s heartbreaking.”

Smith then mentioned his wife and two daughters and wondered what will happen to them when he’s gone. He wondered about the grandchildren he may never see. His voice breaking again, he talked about the excitement of being a young miner, about the hope and promise of good pay and good lives.

“We was all young and strong and stout and they took advantage of us. Every one of us is either crippled or dead. We was all young men,” he said, crying softly.

Smith has a plot picked out for himself in the family cemetery on his property, behind the gravestone of his parents.

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich-Joseph Facun for NPR

Back at his house in a narrow valley — a holler — in Canada, Ky., Smith pointed to a family cemetery on a knoll at the edge of the lawn he has so much difficulty mowing. It features a single gravestone with bright flowers and the names of his parents. Behind it, Smith told us, in the shade, is the burial plot he has picked out for himself. He’s 46 years old.

NPR’s Adelina Lancianese, Barbara Van Woerkom, Katie Lawrie and Cat Schuknecht; Benny Becker and Jeff Young of Ohio Valley ReSource; and Ellen Smith of Mine Safety and Health News contributed to this story.