Donnie Gardiner works behind the scenes at Fenway Park to keep the ballpark operating smoothly.

Jesse Costa/WBUR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jesse Costa/WBUR

One of the toughest jobs in Major League Baseball might belong to Donnie Gardiner.

He’s the facilities superintendent at Fenway Park, the iconic 107-year-old home of the Boston Red Sox. It’s the oldest ballpark in Major League Baseball, and Gardiner’s job is to keep the place running.

That’s no small undertaking: Fenway Park has undergone major renovations in past years, including fixes to the field to help prevent flooding and the addition of more than 14,000 new seats.

To maintain the park, Gardiner puts in hundred-hour weeks, and occasionally sleeps in his office.

The season just started for the Red Sox. Ahead of the team’s home opener on Tuesday, Gardiner has had little time to waste. Water needed to be turned on to the concession stands, generators needed to be tested, emergency lighting needed to be checked and construction needed to be finished.

He bustled around Fenway, moving from the park’s new hot tub room, to the new training room, to the new video coaching room, getting updates and giving advice to workers.

“We have city inspections we have to worry about,” he said. “We have construction we have to finish up. We have just all kinds of things going on right now.”

As he talked, a racket of whirring equipment sounded around him — workers were installing walls, putting ceilings back together, painting, sanding, sawing and hammering.

Some of the challenges in renovating the ballpark are unpredictable, but Gardiner takes it all in stride. After all, he has worked at the ballpark for three decades.

Sometimes, Gardiner must work around brass waterlines that have stood the test of time. Other times, he uncovers remnants from Fenway’s past.

“When we ripped up the concourse a few years ago it was like an archaeological dig, finding the old nip bottles, is what we call them today, old shoes,” he said. “And the place was, I’m assuming, heated by coal because we found a lot of coal ash out in center field.”

Though soft-spoken, Gardiner has a commanding presence. He is constantly making important decisions about the park’s upkeep, and with an area as small as Fenway’s, every decision, every inch, matters.

Gardiner likes to say he’s playing a “game of inches.” With almost every decision, he has to figure out how to make the best use of limited space while preserving the park’s character.

“Everything we’ve done to this place has not taken away from the allure of the park … The feel is still there,” he said. “This building has a feel to it. It does for me personally. I’ve touched every inch of this place at one time or another.”

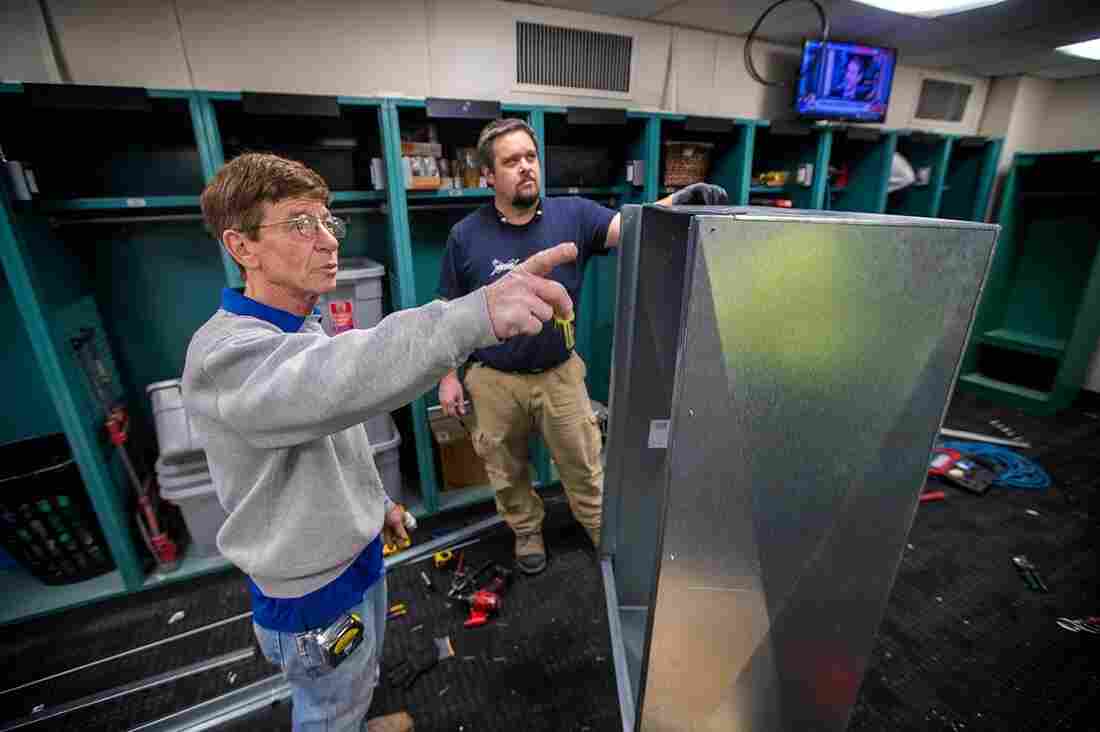

Fenway Park facilities superintendent Donnie Gardiner discusses construction work in the visiting team’s clubhouse with a contractor.

Jesse Costa/WBUR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jesse Costa/WBUR

Aside from fitting in more seats, another upgrade Gardiner has overseen at the ballpark is renovating the clubhouses.

Many teams have outgrown Fenway’s cozy clubhouses, so there’s always plenty of work for Gardiner to do on both the Red Sox’s team clubhouse and for the visiting team’s clubhouse area. All the renovations at the park are done equally.

“I’m not playing one side over the other. Whatever we do for one we do for the other,” he said.

Now that a new season has started, Gardiner’s focus has shifted from renovations to preventative maintenance.

“Game days are actually easier for the most part. If we do our job right the building runs itself.”

Still, Gardiner is typically too busy monitoring what’s happening off the field to pay attention to the game itself.

He takes pride in the green painted walls, the rows and rows of seats crammed onto every space imaginable and the bright stadium lights that shine down on it all.

“It’s unlike any other building,” Gardiner said of Fenway Park. “It’s not Joe’s Pizza. It’s not a high rise. It’s not a supermarket. It’s a very unique building. And the way it’s used is very unique. That’s what I love about it. I’d get bored anywhere else.”

NPR’s Amanda Morris produced this story for digital.