By Sarah Varney

A guard escorts a detained immigrant from his “segregation cell” back into the general population at the Adelanto Detention Facility in November 2013. Today the privately run ICE facility in Adelanto, Calif., houses nearly 2,000 men and women and has come under sharp criticism by the California attorney general and other investigators for health and safety problems.

John Moore/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

John Moore/Getty Images

It’s Saturday morning and the women of the Contreras family are busy in Montclair, Calif., making pupusas, tamales and tacos. They’re working to replace the income of José Contreras, who has been held since last June at Southern California’s Adelanto ICE Processing Center, a privately run immigration detention center.

José’s daughter, Giselle, drives around in an aging minivan collecting food orders. First a hospital, then a car wash, then a local bank.

Giselle’s father crossed from Guatemala more than two decades ago, without authorization to enter the U.S. He worked in construction until agents picked him up and brought him to Adelanto.

Giselle says her father languished there for three months without his diabetes medication. Now, she says, the guards give it to him at odd times during the day and night. And, she says, ICE agents took his eyeglasses so he can’t read legal documents or write letters.

“My aunt tried to take in glasses for him but they don’t allow for us to give them anything,” Giselle tells me as she steers the minivan. “They tell us that they give them everything they need.” When I ask if her father has glasses now, she says, “No, he doesn’t. He doesn’t have glasses.”

Maria Contreras, José’s sister, makes papusas and other food for sale in Southern California — to help support the family while José is in detention at the ICE Adelanto Processing Center. He has been held there for months without his glasses or requested counseling for depression, she says, and doesn’t get his diabetes medication when he needs it.

Sarah Varney/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Sarah Varney/Kaiser Health News

Giselle says her father, who is 60 years old, is terrified of being deported, and she says the regimented world inside Adelanto is driving him into a deep depression. “His conversations now have become shorter,” she says. “He doesn’t talk to us and ask, ‘How’s your day? How you been?’ He’s always looking down at the ground; he doesn’t want to make eye contact for the same reason that he’s so depressed.”

José’s sister, Maria Contreras, visits her brother every Saturday. She has urged him to see a psychologist at Adelanto, but he tells her that even though he filled out a medical request, he doesn’t get any help. “No response, or anything,” Maria says.

Adelanto sits on a desolate stretch of road in the high desert about an hour north of the city of Riverside. Nearly 2,000 men and women are held here. Some arrived recently during the surge in border crossings. Others lived in the U.S. — undocumented and undetected — for years. In the visiting room, where detainees are brought in wearing blue, orange or red baggy pants and tops, a sign on the wall reads, “Don’t give up hope.”

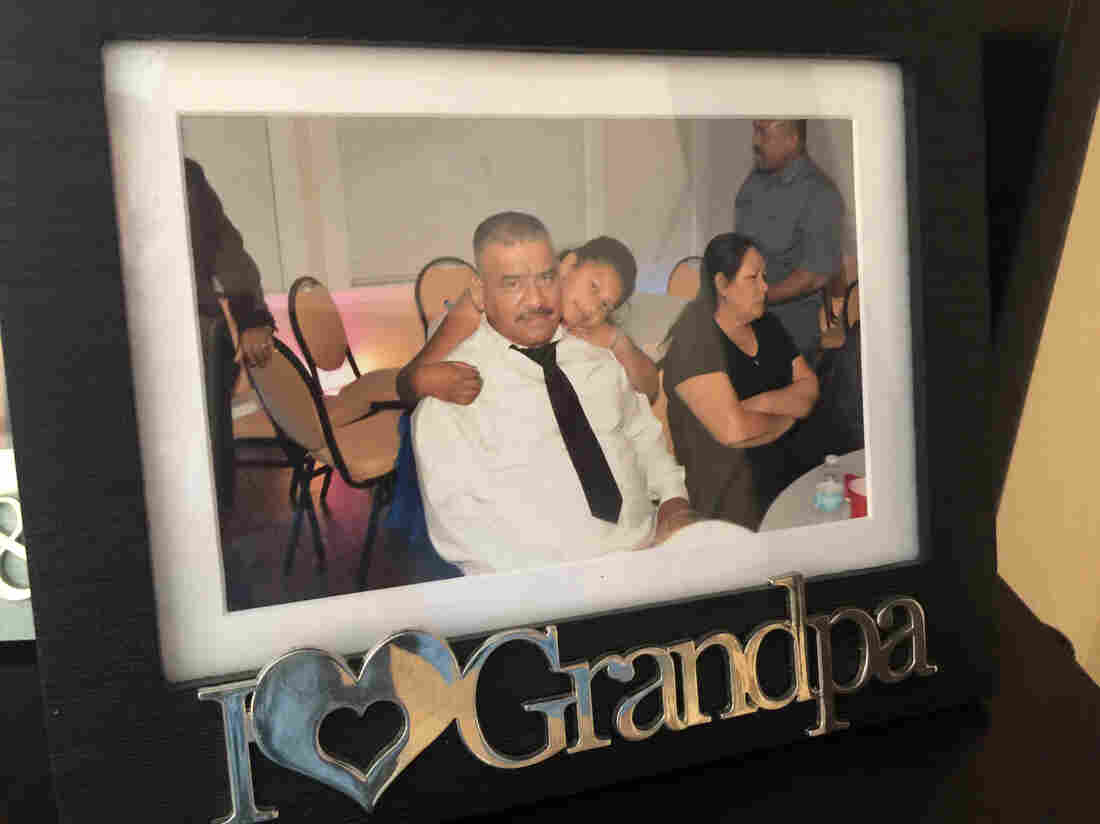

José Contreras with his family, in happier times. He came to the U.S. from Guatemala without authorization more than two decades ago and worked in construction until agents picked him up and took him to Adelanto.

Sarah Varney/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Sarah Varney/Kaiser Health News

The facility — run by a federal contractor, GEO Group, a for-profit company based in Boca Raton, Fla., that runs private prisons — has a troubled past. During an unannounced visit last year, federal inspectors from the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Inspector General found “nooses” made out of bedsheets in 15 out of 20 cells. The inspectors found that guards overlooked the nooses even though a detainee had died by suicide using a bedsheet in 2017 and several others had attempted suicide using a similar method. The government audit concluded GEO Group guards improperly handcuffed and shackled detainees, unnecessarily placed detainees in solitary confinement and failed to provide adequate medical care.

A separate investigation of Adelanto and other immigration detention facilities in California released in February by state Attorney General Xavier Becerra found similar health and safety problems and concluded that detainees were treated like prisoners, some kept in their cells for 22 hours a day, even though they have not been charged with a crime. A state law passed in 2017 directs the state to inspect and report on the treatment of immigrant detainees held in California.

The alleged cases documented in the most recent report by Disability Rights California, a watchdog group with legal oversight to protect people with disabilities in the Golden State, are grim: detainees slitting their wrists; discontinued medication for depression; and ignored requests for wheelchairs and walkers. At least one detainee said that guards pepper-sprayed him when he did not stand up and a second time while he tried to hang himself.

In a written statement, GEO Group says it “strongly disputes the claims” in the report and that the remedies recommended by Disability Rights California “were already in place.”

“We are deeply committed,” the company says, “to delivering high-quality, culturally responsive services in safe and humane environments.” An ICE spokesperson says, in an emailed statement, that GEO Group’s Adelanto facility is in “full compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act.”

But Mario, who was inside Adelanto for six months in 2018, says the report describes his own experiences there. “What’s happening is all those claims that have been made against GEO and the staff in the medical department are finally being backed up by reports,” Mario says.

He asked us not to use his last name since he is out on bond and still fighting deportation. Mario is now 32; he crossed the border with his parents without documentation when he was 5.

In 2017, he was convicted of a misdemeanor and ICE agents picked him up at his home in Ontario, Calif. At the time, Mario was seeing a therapist for depression and taking medication. It took three weeks to get back on antidepressants, he says, and the sessions with the psychologists at Adelanto were only cursory.

“They keep their actual sessions to five to 10 minutes,” he says. “It’s basically like a quick check-in. They just ask you, ‘How are you? Do you have any suicidal thoughts? When is your next court date?’ It’s one of those things that I feel is basically done just to say, ‘All right, we did it.’ “

Mario is gay and lived in a room with three other men, including a gay man from Mexico who was seeking asylum. The two men became close friends.

“He was persecuted in Mexico because of being gay,” Mario says. Months of detention “and not getting any mental health care really took a toll on him. And that’s when he cut himself. He cut his wrist with a razor blade that we get to shave. And after that he was placed in solitary confinement for about a week.”

Mario says when his friend came back to their room, he was taking some sort of medication. “After that, all he did was sleep,” Mario says. “When the food was ready I’d go call him: ‘OK, it’s time to eat.’ “

Other detainees and immigration lawyers described a similar pattern, of GEO psychiatrists prescribing antipsychotic medications that make people sleep much of the time. It’s one of the reasons people were reluctant to seek help, Mario says. But also, like other detainees, he was worried about being labeled as depressed.

“I couldn’t express whenever I was extremely feeling sad or depressed or anxious because I was afraid that would be used against me in court,” he explains.

Judges cannot use mental health conditions to deny legal status to a detainee, according to immigration attorneys.

Last month, long after GEO Group says the company addressed any problems detailed in the Disability Rights California report, detainees in Adelanto staged a hunger strike. The detainees gave an attorney a handwritten note, which was released by the Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice, an advocacy group.

Chief among their demands was speedier access to good medical care.

Sarah Varney is a senior national correspondent at Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit health newsroom that is an editorially independent part of the Kaiser Family Foundation.