By Sammy Caiola

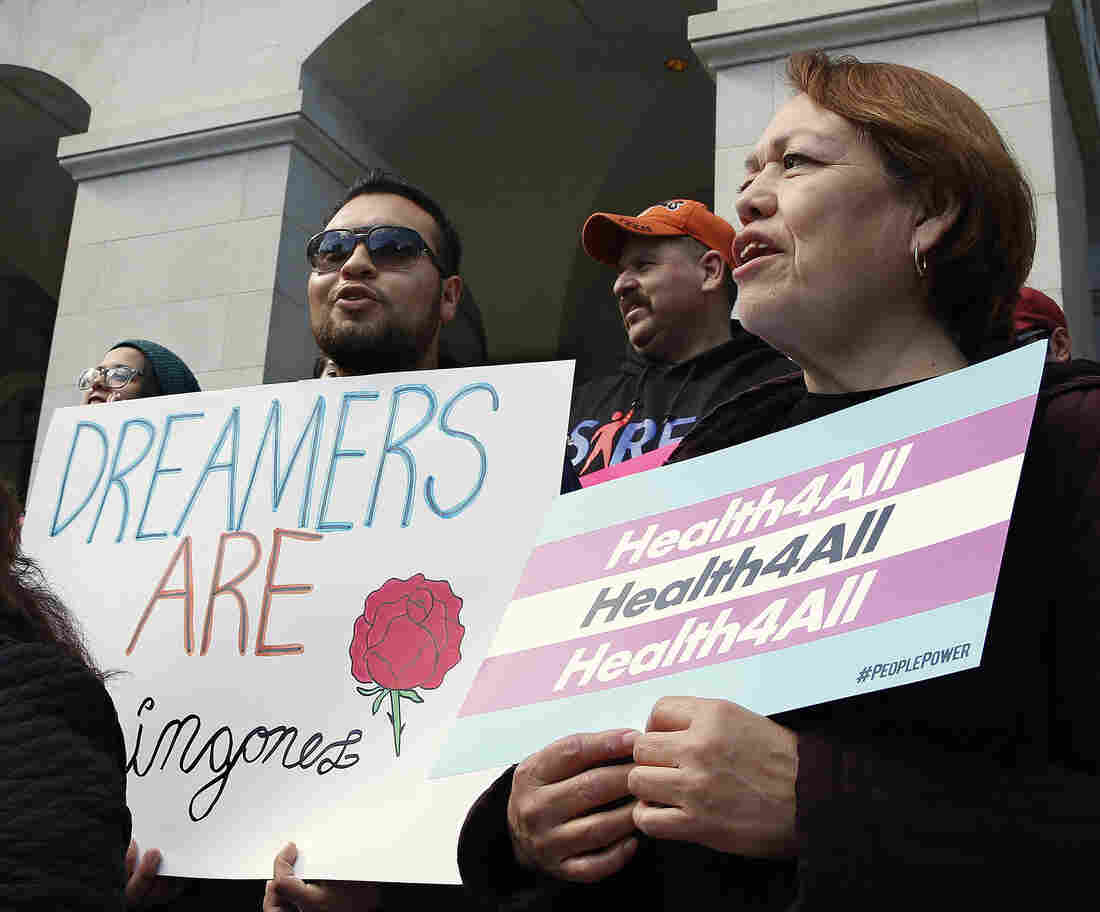

Demonstrators rallied in Sacramento in May for Medi-Cal expansion to undocumented Californians. When the state’s budget was finalized, only young adults up to age 26 were authorized to be included in the expansion. Gov. Gavin Newsom says that’s an important first step.

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

For years, Beatriz Basurto’s family has had to make hard choices about when to pay for medical care, and who should get treatment.

“To me, it was always the doctor would be the last resort,” she says. “But for my parents, the doctor was never a choice. No matter how sick they got, they had to suck it up.”

Basurto, 19, says her parents always put the kids’ medical needs before their own. The family moved to California from Mexico more than 15 years ago. During that time, most of her family members have been ineligible for Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid, because they aren’t citizens.

Their situation started to change in 2016, when California expanded the program to all low-income children 18 and under, regardless of immigration status. That opened the doors for Basurto’s little sister to enroll.

And starting in January of 2020, Beatriz will be allowed to sign up, too.

California’s governor signed a law Tuesday that approved $98 million to expand Medi-Cal to income-eligible undocumented adults from age 19 until they turn 26, making it the first state in the United States to cover this group. California estimates 138,000 young adults will become insured under the new policy.

While the state has expanded options for children and young adults, most undocumented people in California still have limited access to health care. They can sign up for “restricted” Medi-Cal, but it only covers emergencies and pregnancy-related care. Many people on this plan end up putting off treatment or turning to county clinics for help.

Supporters who want to further expand Medi-Cal to all residents say that move would boost public health and bring down emergency room costs. California Gov. Gavin Newsom has vowed to make everyone eligible.

“We believe in universal health care,” he said during a speech this month. “Universal health care’s a right, and we’re delivering it — regardless of immigration status — to everyone up to the age of 26, and we’re gonna get the rest of that done, mark my words.”

But after months of debate at the California State Capitol, proposals to offer Medi-Cal to all undocumented adults, as well as a push to cover undocumented seniors, were deemed too costly.

Medicaid is a joint state-federal program, but California would use state dollars to pay for expanded benefits to immigrants living in the U.S. without legal permission.

Some lawmakers argued California should be spending health care dollars on its own citizens, rather than people who are not living in the state legally.

“We are going to be a magnet that is going to further attract people to a state of California that’s willing to write a blank check to anyone that wants to come here,” said state Sen. Jeff Stone, a Republican, at a recent legislative hearing.

President Donald Trump also criticized California for offering health insurance to undocumented people.

“They don’t treat their people as well as they treat illegal immigrants,” the Republican president told reporters in the White House on Monday. “It’s very unfair to our citizens and we’re going to stop it, but we may need an election to stop it.”

But advocates say California isn’t done fighting for Medicaid expansion.

Almas Sayeed, deputy director of the California Immigrant Policy Center, says providing health care is crucial, given federal anti-immigrant hostility.

“For young immigrants, it’s a moment of feeling like we don’t belong in this country,” she says. “We work really hard in California to make sure communities know that they do.”

Beatriz Basurto is eager to sign up for Medi-Cal this January. She attends community college near Los Angeles, and wants to become an environmental scientist. She hopes getting insurance will allow her to seek out mental health care for ongoing stress, some of which she attributes to hostile political rhetoric about immigrants.

“The world isn’t always so welcoming,” she says. “It can be really, really overwhelming. It exhausts you mentally. It’s almost like I have no time to feel anything, because there’s always something else I have to do.”

Brenda Huerta, an undocumented 22-year-old, was enrolled in a health plan through her university. But that coverage expired this summer, after she graduated. She says her college plan was great for checkups, but didn’t cover large expenses.

When Huerta broke her leg she ended up paying for her care out-of-pocket. And she’s still helping pay off hospital bills from when her mom had major surgery.

Huerta needs new glasses, and she wants to continue regular medical and dental care. But she isn’t sure if she’ll sign up for Medi-Cal next year. Even with coverage, she’s worried her costs will stack up.

“Paying the [student] loans that I have, I haven’t really been thinking about health insurance,” she says.

She and other young adults recently met with Gov. Gavin Newsom to lobby for the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to all Californians.

“Everyone in the room, we did talk about our struggles as undocumented people not having health insurance,” she says. “And we also mentioned how our parents suffer from not having health insurance, because it puts an economic burden on us.”

Newsom’s office estimated expanding eligibility to all undocumented adults would cost $3.4 billion. About two thirds of California’s roughly 2.2 million undocumented immigrants would qualify for Medi-Cal based on income guidelines.

Basurto says even though coverage for undocumented young adults is a small step in the larger battle for equal rights, it makes her feel more at home in the U.S.

“I do belong here,” she says, “regardless of what others say.”

This story is part of NPR’s health reporting collaboration with Capital Public Radio and Kaiser Health News.