Barbershop: NFL’s 100th Season

To mark the NFL’s 100th anniversary, NPR’s Michel Martin talks football with The Nation’s Dave Zirin, Jason Reid of ESPN’s The Undefeated, and journalism professor Kevin Blackistone.

To mark the NFL’s 100th anniversary, NPR’s Michel Martin talks football with The Nation’s Dave Zirin, Jason Reid of ESPN’s The Undefeated, and journalism professor Kevin Blackistone.

The U.S. Open is well underway and Serena Williams is, unsurprisingly, in the finals. The NFL’s opening night was underwhelming. And more girls than ever are signed up to play high school football.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

How nice it is to find time for sports.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

SIMON: Serena Williams on the verge of history again. The regular NFL season has begun with a long, dull splat. And are more young women interested in getting their heads rattled too? We’re joined now, as always, by NPR’s Tom Goldman. Tom, thanks so much for being with us.

TOM GOLDMAN, BYLINE: Thank you, Scott.

SIMON: U.S. Open – Serena Williams going for what would be a record-tying 24th Grand Slam win. But there’s a 19-year-old on the other side of the net. How do you see today’s match?

GOLDMAN: I see victory. I see the great…

SIMON: For one of the players, yes. But yes, yeah.

GOLDMAN: (Laughter) Oh, OK, for Serena Williams.

SIMON: Yeah.

GOLDMAN: I see Serena reversing recent history. You know, since her return to tennis after becoming a mother, she’s been in three Grand Slam finals and lost all three. And she has looked rattled. Each of those losses was preceded by a strong showing in the semifinal match.

Now, the U.S. Open has followed that pattern. She’s looked really good coming into this final against 19-year-old, Canadian Bianca Andreescu. So why do I see victory, Scott?

SIMON: Why do you see victory, Tom Goldman?

GOLDMAN: Thank you for asking. Because both Williams and her coach say she is finally healthy. She’s battled injuries this year. Now they say she’s physically ready, and that helps her mental approach. In her words, she says she has been way more chill than in the past. And, Scott, I believe her.

SIMON: Yeah, well, she knows. Rafael Nadal is the last of the big three standing on the men’s side. What do you see there?

GOLDMAN: Well, we’ve seen the big three teeter this tournament. Novak Djokovic pulled out with an injury. Roger Federer lost in the quarterfinals, largely because he was hurt, although he refused to blame that. You know, there’s all this speculation – is the big three reign over? I mean, someday it will be, someday soon. But Federer, the oldest of them at 38, he has been playing great, and no reason he can’t still at 39 if the body holds up. For now, though, as you say, Nadal is left. He plays in tomorrow’s final. And he has a chance to win his 19th major title, putting him one behind the leader, Federer.

SIMON: Yeah. NFL season opened – Green Bay Packers versus the Chicago Bears…

GOLDMAN: (Imitating snoring noises).

SIMON: …With their headliner Eddie Goldman, the fabulous Eddie Goldman. This is the oldest rivalry in football – all the makings of a classic, except the game. You watched all three hours. If you had to put a highlight reel together, how many seconds would be in there?

GOLDMAN: Not many. Can I get those three hours back? I don’t think I can. It was a 10-3 snore-fest, although NFL aficionados – and there are many – will say that shows my ignorance because it was a defensive masterpiece.

SIMON: Right, yes.

GOLDMAN: Well, there was a lot – there were a lot of penalties and bad offense, too. Scott, I love a great defensive play now and then, but give me touchdowns, long touchdowns.

SIMON: At least one, I think there was one. Yeah, yeah.

GOLDMAN: Lots of – lots of them. Come on, guys. And hopefully, the offenses will start waking up tomorrow.

SIMON: I want to ask you about a development in high school football, and I have divided thoughts about it. Recent numbers show that more girls, young women, than ever are participating in tackle football at the high school level. I have a hard time cheering the fact that young women athletes now stand – want an equal chance to suffer head trauma.

GOLDMAN: Yeah, well, it’s a good point. And some will agree with you. We will note this interesting development, however. The National Federation of State High School Associations says last season, more than 2,400 girls played 11-man, or shall we say 11-person, tackle football on high school boys’ teams. Now, that’s only 0.2% of the total, but it’s an increase for the fourth straight year, and this at a time when participation by boys has been declining. California leads the way with 593 girls who played. New Jersey, Texas, Colorado also had more than 100, so an interesting development.

SIMON: NPR’s Tom Goldman. Thanks so much.

GOLDMAN: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Supporters of safe injection sites in Philadelphia rallied outside this week’s federal hearing. The judge’s ultimate ruling will determine if the proposed “Safehouse” facility to prevent deaths from opioid overdose would violate the federal Controlled Substances Act.

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

Philadelphia could become the first U.S. city to offer opioid users a place to inject drugs under medical supervision. But lawyers for the Trump administration are trying to block the effort, citing a 1980s-era law known as “the crack house statute.”

Justice Department lawyers argued in federal court Thursday against Safehouse, the nonprofit organization that wants to open the site.

U.S. Attorney William McSwain, in a rare move, argued the case himself. He says Safehouse’s intended activities would clearly violate a portion of the federal Controlled Substances Act that makes it illegal to manage any place for the purpose of unlawfully using a controlled substance. The statute was added to the broader legislation in the mid-1980s at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic in American cities.

Safehouse argues the law does not apply because the nonprofit’s main purpose is saving lives, not providing illegal drugs. Its board members say that the “crack house statute” was not designed to be applied in the face of a public health emergency.

“Do you think that Congress would want to send volunteer nurses and doctors to prison?” asked former Philadelphia Mayor and Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell, who is on Safehouse’s board, after the hearing. “Do you think that’s a legitimate result of this statute? Of course not. No one could have ever contemplated that, ever!”

Safehouse earned the backing of Philadelphia’s mayor, health department, and district attorney, who announced they would support a supervised injection site in January 2018 as another tool to combat the city’s dire overdose crisis.

More than 1,100 people died of overdoses in Philadelphia in 2018 — an average of three people a day. That’s triple the city’s homicide rate.

In response, public health advocates and medical professionals teamed up with the operators of the city’s only syringe exchange to found Safehouse. They created a plan for its operations, and began scouting a location.

But the Trump Administration sued the nonprofit in February to block the supervised injection site from opening.

In June, the Justice Department filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings– essentially asking the judge to rule on the case based on the arguments that had already been submitted. Since then, a range of parties have filed amicus briefs in support of or in opposition to the site. Attorneys general, mayors, and governors from across the country filed briefs backing Safehouse, while several neighborhood associations in Kensington and the police union filed against it.

U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh requested an evidentiary hearing to learn more about the nuts and bolts of how the facility would work, were it to open. At that hearing, in August, Safehouse’s legal team, led by Ilana H. Eisenstein, explained that Safehouse would not provide drugs, but that people could bring their own to inject while medical professionals stood by with naloxone, the overdose reversal drug. They said Safehouse would also be an opportunity for people to get access to treatment, if they were ready to commit to that.

Safehouse vice president Ronda Goldfein said the only difference between what Safehouse would do — and what’s already happening at federally sanctioned needle exchanges and the city’s emergency departments — is permit drug injection to happen in a safe, comfortable place.

“If the law allows for the provision of clean equipment, and the law allows for the provision of naloxone to save your life, does the law really not allow you to provide support in that thin sliver in between those federal[ly] permissible activities?” she said.

McSwain contends operating in that “sliver” is exactly what makes Safehouse illegal.

Much of the debate at Thursday’s hearing revolved around interpreting the word “purpose.” The statute in the Controlled Substances Act makes it illegal for anyone to “knowingly open … use or maintain any place … for the purpose of … using any controlled substance.”

The federal government says it’s simple: Safehouse’s purpose is for people to use drugs. McSwain conceded the facility will also provide access to treatment, but so does Prevention Point, the city’s only syringe exchange. Effectively, he argued, the only difference between Safehouse and what’s already going on elsewhere would be that people could inject drugs at Safehouse, which is prohibited by the statute.

“If this opens up, the whole point of it existing is for addicts to come and use drugs,” McSwain said.

Safehouse said its purpose is to keep people at risk of overdose from dying.

“I dispute the idea that we’re inviting people for drug use,” Eisenstein argued.

“We’re inviting people to stay to be proximal to medical support.”

McSwain conceded that if Safehouse were to offer the medical support without opening up a space specifically for people to use drugs, the statute would not apply.

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney spoke Thursday in support of the Safehouse injection site to reduce the number of deadly overdoses in Philadelphia. More than 1,100 people died of overdoses in the city in 2018 — an average of three people a day.

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

“If Safehouse pulled an emergency truck up to the park where people are shooting up, I don’t think [the statute] would reach that. If they had people come into the unit, that would be different,” he said. Mobile units and tents in parks are supervised injection models that other cities like Montreal and Vancouver have implemented.

Safehouse has also said it hasn’t ruled out the idea that it might incorporate a supervised injection site into another medical facility or community center, which would indisputably have other purposes, as well.

McSwain ultimately argued that Safehouse had come to the “steps of the wrong institution,” and that if it wanted to change the law, it should appeal to Congress. He accused Safehouse’s board of hubris, pointing to Safehouse president Jose Benitez‘s testimony at the August hearing, where he acknowledged that they hadn’t tried to open a site until now because they feared the federal government would think it was illegal and might shut it down.

“What’s changed?” asked McSwain. “Safehouse just got to the point where they thought they knew better.”

“Either that, or it’s the death toll,” Judge McHugh replied.

Supervised injection sites are used widely in Canada and Europe, and studies have shown that they can reduce overdose deaths and instances of injection-related diseases like HIV and hepatitis C. San Francisco, Seattle, New York City, Ithaca, N.Y., and Pittsburgh, Pa., among other U.S. cities, have expressed interest in opening a similar site, and are watching the Philadelphia case closely. In 2016, a nonprofit in Boston opened a room where people can go after injecting drugs, to ride out their high. The room has nurses equipped with naloxone standing by.

The Justice Department’s motion for the judge to rule on the pleadings is still pending. McHugh could decide he now has enough information to issue a ruling, or he might request more hearings, arguments or a full fledged trial.

Safehouse’s legal team said this week that if the judge rules in its favor, it might request a preliminary injunction in the form of relief — to allow the facility to open early.

“We recognize there’s a crisis here,” said Safehouse’s Goldfien. “The goal would be to open as soon as possible.”

This story is part of NPR‘s reporting partnership with WHYY and Kaiser Health News.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WHYY and Kaiser Health News.

Beth Malcolm

Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the artist

Hear musicians from both sides of the Atlantic making their first appearances on our show. Artists include Beth Malcolm, a new duo for Tony McManus and a welcomed return from a band last aired in the days of vinyl.

Barrule

Phil Kneen/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Phil Kneen/Courtesy of the artist

Hear the haunting melodies from St. Kilda that offer a last link to the “island on the edge of the world,” with Julie Fowlis and Barrule.

Dr. Peter Grinspoon was a practicing physician when he became addicted to opioids. When he got caught, Grinspoon wasn’t allowed access to what’s now the standard treatment for addiction — buprenorphine or methadone (in addition to counseling) — precisely because he was a doctor.

/Tony Luong for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

/Tony Luong for NPR

Peter Grinspoon got addicted to Vicodin in medical school, and still had an opioid addiction five years into practice as a primary care physician.

Then, in February 2005, he got caught.

“In my addicted mindframe, I was writing prescriptions for a nanny who had since returned back to another country,” he says. “It didn’t take the pharmacist long to figure out that I was not a 19-year-old nanny from New Zealand.”

One day, during lunch, the state police and the DEA showed up at his medical office in Boston.

“I start going all, ‘I’m glad you’re here. How can I help you?’ ” he says. “And they’re like, ‘Doc, cut the crap. We know you’re writing bad scripts.’ “

He was fingerprinted the next day and charged with three felony counts of fraudulently obtaining a controlled substance.

He also was immediately referred to a Physician Health Program, one of the state-run specialty treatment programs developed in the 1970s by physicians to help fellow physicians beat addiction. Known to doctors as PHPs, these programs now cover other sorts of health providers, too.

The programs work with state medical licensing boards — if you follow the treatment and monitoring plan they set up for you, they’ll recommend to the board that you get your medical license back, Grinspoon explains. It’s a significant incentive.

“The PHPs basically say, ‘Do whatever we say or we won’t give you a letter that will help you get back to work,’ ” Grinspoon says. “They put a gun to your head.”

But the problem, he and other critics say, is that, for various reasons, most PHPs don’t allow medical professionals access to the same evidence-based, “gold standard” treatment that addiction specialists today recommend for most patients addicted to opioids: medication-assisted treatment.

Grinspoon was told that to avoid a criminal record he would need to spend 90-days at an inpatient center in Virginia; there, he was not allowed access to the most common MAT prescription of counseling plus buprenorphine or methadone. These drugs are particular members of the opioid family that have been shown to suppress cravings for heroin, fentanyl and other frequently abused opioids. (Another drug, naltrexone, works by blocking opioids’ action, and is also sometimes prescribed as a component of medication-assisted treatment.)

“Why would you send this Jewish atheist to a religious, Christian rehab place in Virginia?” Grinspoon says. “It didn’t make any sense. I was just sitting there listening to people recite the Lord’s Prayer and hold hands. And I’m not against the Lord’s Prayer, but it just didn’t help me.”

At the same time, Grinspoon was forced off all the drugs he’d been taking “cold turkey,” without the medical support that would have eased withdrawal pangs and cravings. “It was completely insane,” he says.

“Why on earth,” Grinspoon adds, “would you deny physicians — who are under so much stress and who have a higher access and a higher addiction rate — why would you deny them the one lifesaving treatment for this deadly disease that’s killing more people in this country every year than died in the entire Vietnam War? There’s no reason for it.”

Grinspoon eventually recovered, but only, he says, after going through several “awful” rehab experiences. “I recovered despite going to rehab not because I went to rehab,” he says.

Today, he is a licensed primary care doctor and teaches at Harvard Medical School. He has also written a book about his experience with addiction called Free Refills.

Addiction specialists call for an end to the medication ‘ban’

While there is some variation in the particular rules and policies that each state’s physician health program follows, Dr. Sarah Wakeman of Harvard and the Massachusetts General Hospital Substance Use Disorder Initiative, says most PHPs don’t refer patients to addiction programs that include medication as part of their treatment. And that’s a problem, she says.

“I think the underlying issue is stigma and a misunderstanding of the role of medication,” Wakeman says, “and this idea that a non-medication-based approach is somehow better than someone taking the medication to control their illness.”

She co-authored a recent opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Practicing What We Preach — Ending Physician Health Program Bans on Opioid-Agonist Therapy,” along with collaborators Leo Beletsky and Dr. Kevin Fiscella.

“Systematically denying clinicians access to effective therapy is bad medicine, bad policy and discriminatory,” they write in NEJM. “We call on the health care sector to practice what it preaches, by discarding this antiquated norm.”

“It’s the peak of hypocrisy and absurdity,” Beletsky, a professor of law at Northeastern University tells NPR.

“I work with a lot of folks who are health professionals themselves, who are on the front lines advocating and fighting against stigma, trying to get policies and practices to align more closely with the science,” he says. “If those very same people were themselves struggling with addiction they would not have access to those medications.”

The strict policies of PHPs might have a chilling effect on health professionals who have opioid use disorder and need help, Beletsky and Wakeman believe.

A proven record, and reasons for caution

So what do the institutions getting blamed here — Physician Health Programs — have to say about all this?

Dr. Christopher Bundy is the executive medical director of Washington state’s PHP and the president-elect of the Federation of State Physician Health Programs.

He wants to make clear, first of all, that there is no systematic ban against the use of medication-assisted treatment, and no health care provider should avoid seeking help.

“There are doctors today across the country who are being monitored on buprenorphine,” he says. “And not just physicians. Nurses and other health professionals — certainly nurses in our state are able to work on buprenorphine.”

Bundy acknowledges, though, that those cases are not the norm.

There are “rational and understandable reasons,” he says, why such medications are often not used in rehab programs aimed at health professionals.

For example, he cites concerns that medications like buprenorphine can affect cognition. PHPs also get pressure from other stakeholders, such as regulators and licensing boards not to use medication. And, he points out, the in-patient, non-medication treatment model has been proven to work with many health professionals across several decades, and he worries that changing it could open PHPs up to unnecessary risk.

“Our tendency is to err on the side of caution,” Bundy says, “especially when implementing therapies that have the potential to impair somebody’s ability to practice safely. Despite the fact that there are many who would like us all to believe that the jury is in [on medications like buprenorphine], more remains unknown than known, especially when it comes to how to appropriately use these medications in safety-sensitive professionals.” That includes some other professions, such as pilots, he says — not just health workers.

Bundy notes that the public trusts PHPs to help health workers get healthy enough to be able to work with patients again — and that trust is fragile.

“We only need to have a case of one physician who is on buprenorphine where there’s a bad patient outcome,” he says, “to potentially have a whole other source of criticism being levied against the PHP for putting that physician back to work on a medication that may have played a role in that bad outcome.”

An overwhelming process

Bill Kinkle, a nurse in recovery from opioid use disorder, is right now going through the laborious process of getting his nursing license back. He lives outside of Philadelphia and is very public about his past drug use — he even has a podcast called “Health Professionals in Recovery.”

He’s working through an extensive treatment and monitoring program to get his nursing license back. Kinkle hopes to complete his third year of documented sobriety next fall; if so, he’ll then be eligible to practice nursing again.

When he was in the throes of his addiction and desperate to get into recovery, Kinkle says he was scared to do anything that might jeopardize his chance to get his career back.

Independence Blue Cross Foundation

YouTube

“In the nursing community, there is a ton of fear about the PHPs,” he says. “Everybody always told me, ‘You can’t be on Suboxone [a form of buprenorphine] — you can’t be on anything.'”

But he wanted to check for himself. So he called his state’s PHP to ask what their policy actually was.

” ‘The Board of Nursing will send you for some type of extensive cognitive testing,’ ” he says he was told. ” ‘Number one, the testing is very expensive. And it’s very difficult to find someone that will do the testing that we require.’ “

Daunted by that response, Kinkle says he instead “white knuckled it.” He went to abstinence-based programs — over and over again, and over and over. Many, many times, as soon as the rehab ended, Kinkle would relapse and turn to opioids again.

“A lot of those, I overdosed,” he says. “And had my wife not found me on the floor and been able to take care of me, I very well may have died.”

Kinkle believes “all that possibly could have been mitigated, had I gotten the gold standard of treatment, which is either buprenorphine or methadone.”

He doesn’t fault PHPs or licensing boards for their problematic policies, even though he thinks those policies put his life at risk. He says the stigma associated with addiction is ingrained in our culture; there’s no single institution to blame.

Both sides of the table

Peter Grinspoon was monitored in his recovery from opioid dependence by a PHP for seven years; and then later went to work for that very program.

“I’ve seen this issue from both sides,” he says. “I actually sat at the same table — in 2005 looking like something the cat dragged in, and then from 2013 to 2015 as a physician in recovery, helping other doctors.”

Grinspoon eventually wrote a book about his experiences and now works as a doctor at Mass General Hospital in Boston.

/Tony Luong for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

/Tony Luong for NPR

Grinspoon says in his experience, there was a de facto ban on medication-assisted treatment. In his state the ban was based, he says, on the assumption that the licensing board would reject any doctor-applicant who was taking a medication like buprenorphine. He says the feeling among staff at the PHP was “why bother to set someone up for failure?”

He believes such a policy needs to change, and that any cited concerns about cognitive impairment associated with medication-assisted treatment are unproven — and hypocritical.

“Why do they make medical students, interns and residents work 28-hour shifts then?” he points out. “I’d rather have someone on Suboxone [treat me] than someone who’s been up all night. And doctors are allowed to drink the night before [they go to work] — they’re allowed to take Ambien for sleep. That totally impairs you the next day.”

“This is pure stigma,” Grinspoon says. “It’s harming doctors. They need to reevaluate this completely.”

As research into head injuries expands to include women’s soccer, some of the sport’s former stars are calling attention to the health fallout from heading the ball multiple times.

Opioid addiction can happen to anyone, and that includes doctors and nurses. But unlike the general population, they are often barred from medications like methadone, the gold standard of treatment.

Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, seen at a sentencing hearing last year in Charlotte, Mich. On Thursday, the Department of Education fined the university $4.5 million for its response to Nassar’s conduct while he was employed by the school.

Rena Laverty/AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Rena Laverty/AFP/Getty Images

Updated at 1:15 p.m. ET

The U.S. Department of Education has levied a $4.5 million fine against Michigan State University for its “systemic failure” to address the sexual abuse committed by Larry Nassar, the MSU and USA Gymnastics doctor who admitted to sexually assaulting his patients for decades.

The fine that was announced Thursday came after two investigations ordered by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

“What happened at Michigan State University was abhorrent,” DeVos told reporters by telephone Thursday. “The crimes for which Larry Nassar and [former Michigan State Dean] William Strampel have been convicted are disgusting and unimaginable. So, too, was the university’s response to their crimes. This must not happen again — there or anywhere else.”

Last year Nassar was sentenced to up to 175 years in prison for abusing dozens of girls and young women under the guise of providing medical treatment. He was also hit with a separate sentence of up to 125 years for the abuse and an additional 60-year federal prison term for child pornography.

Strampel led Michigan State’s college of osteopathic medicine and oversaw Nassar during the doctor’s tenure at the school. Strampel, too, faces prison time for his role in the abuse scandal: In June, he was convicted of two counts of willful neglect of duty and one count of felony misconduct for sexually harassing female students in his own right.

The investigations — one conducted by the federal Office of Civil Rights, the other by the office of Federal Student Aid — found that despite having received reports of sexual violence, Michigan State failed to properly disclose the incidents, notify campus security authorities or issue timely warnings about what was going on. The school was also found to have violated the terms of Title IX, a federal statute that bans sex discrimination in education programs that receive federal funding.

“Too many people in power knew about the behaviors and the complaints,” DeVos said, “and yet the predators continued on the payroll and abused even more students.”

As part of its punishment, the university must establish a new office dedicated to complying with federal regulations and also “create a system of protective measures and expanded reporting to better ensure the safety” of students and minor children who visit the campus, the Department of Education says.

Of the $4.5 million fine, the Department of Education says it is a record for punishments of this type. But the fine is not likely to make a dent in the university’s finances: As of the end of June, Michigan State said its endowment was estimated to be $2.9 billion. The Department of Education did not immediately clarify where the money from Thursday’s fine will be directed.

The fine is part of the school’s settlement with the Department of Education, which also stipulates that “nothing in this Agreement constitutes an admission of liability or wrongdoing by MSU.”

Still, MSU President Samuel L. Stanley — whose predecessor resigned last year and faces criminal charges of her own for the Nassar scandal — said Thursday the federal findings are “very clear that the provost and former president failed to take appropriate action on behalf of the university to address reports of inappropriate behavior and conduct, specifically related to former Dean William Strampel.”

“I’m grateful for the thoroughness of these investigations and intend to use them as a blueprint for action,” Stanley added in his statement.

In an op-ed published Thursday in the Louisville Courier-Journal, the lead state prosecutor in the case against Nassar, Angela Povilaitis, said credit for taking down Nassar should go to the first victim to go public with her story, Rachael Denhollander.

“When the judge issued a gag order prohibiting victims from speaking publicly, Rachael challenged the order in federal court (and won). And when 204 women and girls stood up to Nassar at the historic sentencing hearings, Rachael was there for support, every single day, watching those victims become survivors,” Povilaitis wrote.

“She inspired greater oversight of national sports bodies,” she added. “But her greatest contribution may be to the untold number of girls who will never meet Larry Nassar.”

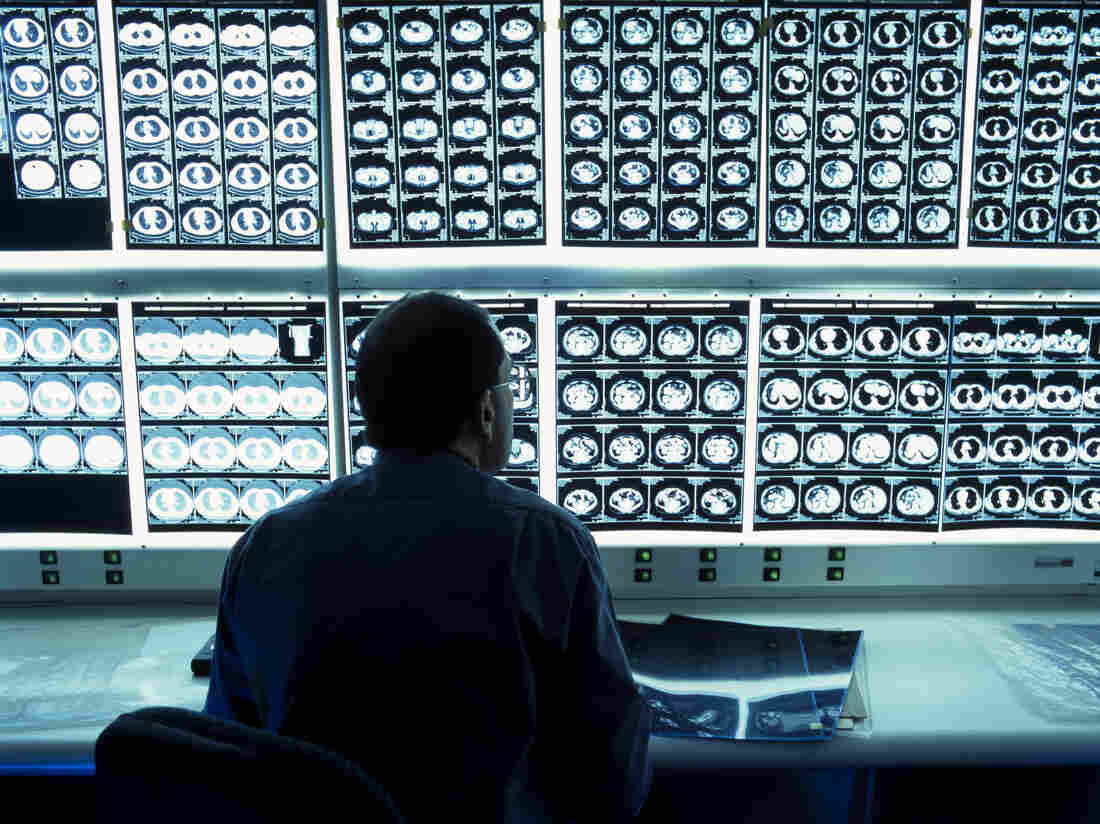

Groupon and other deal sites are the latest marketing tactic in medicine, offering bargain prices for services such as CT scans.

Colin Cuthbert/Science Photo Libra/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Colin Cuthbert/Science Photo Libra/Getty Images

Emory University medical fellow Dr. Nicole Herbst was shocked when she saw three patients who came in with abnormal results from chest CT scans they had bought on Groupon.

Yes, Groupon — the online coupon mecca that also sells discounted fitness classes and foosball tables.

Saw 3 pts in clinic for abnormal chest CTs BOUGHT ON GROUPON.

Evolution of my thoughts:

-What the $@&#? (*Google it*)

-hm actually priced pretty reasonably ?

-jeez if I ever need testing I’m going w/ Groupon, prob cheaper than insurance ????US healthcare is bonkers

— Nicole Herbst (@NicoleHerbst2) August 25, 2019

Similar deals have shown up for various lung, heart and full-body scans across Atlanta, as well as in Oklahoma and California. Groupon also offers discount coupons for expectant parents looking for ultrasounds, sold as “fetal memories.”

While Herbst declined to comment for this story, her sentiments were shared widely by the medical community on social media. The concept of patients using Groupons to get discounted medical care elicited the typical stages of Twitter grief: anger, bargaining and acceptance that this is the medical system today in the United States.

But, ultimately, the use of Groupon and other pricing tools is symptomatic of a health care market where patients desperately want a deal — or at least tools that better nail down their costs before they get care.

“Whether or not a person may philosophically agree that medicine is a business, it is a market,” says Steven Howard, who runs Saint Louis University’s health administration program.

By offering an upfront cost on a coupon site such as Groupon, medical companies are meeting people where they are, Howard argues. It helps drive prices down, he says — all the while marketing the medical businesses.

For Paul Ketchel, CEO and founder of MDsave, a site that contracts with providers to offer discount-priced vouchers on bundled medical treatments and services, the use of medical Groupons and his company’s success speak to the brokenness of the U.S. health care system.

MDsave offers deals at more than 250 hospitals around the country, selling vouchers for anything from MRIs to back surgery. It has experienced rapid growth and expansion in the several years since its launch.

Ketchel credits that growth to the general lack of price transparency in the U.S. health care industry amid rising costs to consumers. “All we are really doing is applying the e-commerce concepts and engineering concepts that have been applied to other industries to health care,” he argues.

“We are like transacting with Expedia or Kayak,” Ketchel says, “while the rest of the health care industry is working with an old-school travel agent.”

A closer look at those deals

Crown Valley Imaging, in Mission Viejo, Calif., has been selling Groupon deals for services including heart scans and full-body CT scans since February 2017 — despite what Crown Valley’s president, Sami Beydoun, called Groupon’s aggressive financial practices. According to him, Groupon dictates the price for its deals based on the competition in the area — and then takes a substantial cut.

“They take about half. It’s kind of brutal. It’s a tough place to market,” Beydoun says. “But, the way I look at it is you’re getting decent marketing.”

Groupon-type deals for health care aren’t new. They were more popular in 2011, 2012 and 2013, when Groupon and its then-competitor LivingSocial were at their height, but the industry has since lost some steam. Groupon stock and valuation have tumbled in recent years, even after buying LivingSocial in 2016.

Groupon did not respond to requests for comment on how many medical offerings it features or its pricing structure.

“Groupon is pleased any time we can save customers time and money on elective services that are important to their daily lives,” spokesman Nicholas Halliwell writes in an emailed statement. “Our marketplace of local services brings affordable dental, chiropractic and eye care, among other procedures and treatments, to our more than 46 million customers daily and helps thousands of medical professional[s] advertise and grow their practices.”

In Atlanta, two imaging centers that each offered discount coupons from Groupon say the deals have driven in new business. Bobbi Henderson, the office manager for Virtual Imaging’s Perimeter Center, says the group has been running the deal for a heart CT scan, complete with consultation, since 2012; it’s currently listed at $26 — a 96% discount. More than 5,000 of the company’s coupons have been sold, according to the Groupon site.

Brittany Swanson, who works in the front office at OutPatient Imaging in the Buckhead neighborhood of Atlanta, says she has seen hundreds of customers come through since the center posted Groupon coupons for mammograms, body scans and other screenings around six months ago. Why did the medical practice turn to Groupon discounts?

“Honestly, we saw the other competition had it,” Swanson says.

A lot of the deals offered are for preventive scans, she says, providing patients incentives to come in.

But Dr. Andrew Bierhals, a radiology safety expert at Washington University in St. Louis’ Edward Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, warns that such deals may be leading patients to get unnecessary initial scans — which can lead to unnecessary tests and radiation.

“If you’re going to have any type of medical testing done, I would make sure you discuss with your primary care provider or practitioner,” he cautions.

Appealing to patients who fall through an insurance gap

Because mammograms are typically covered by insurance, Swanson says, she believes OutPatient Imaging’s $99 Groupon deal is filling a gap for women who lack insurance. The cost of such breast screenings for those who don’t have insurance varies widely but can be up to several hundred dollars without a discount.

Howard says Groupon has long been used to fill insurance gaps for dental care. He often bought such deals over the years to get cheaper dental cleanings when he didn’t have insurance that covered that.

But advanced medical scans involve a higher level of scrutiny, as Chicagoan Anna Beck recently learned. In 2015, she and her husband, Miguel Centeno, were told he needed to get a chest CT after a less advanced X-ray at an urgent care center showed something suspicious.

Since her husband had just been laid off and did not have insurance, they shopped online to look for the cheapest price. They ended up driving out to the suburbs to get a CT scan at an imaging center there.

“I knew that CT scans had such a wide range of costs in a hospital setting,” Beck says. “So going in knowing that I could price check and have some idea of how much I’d be paying and a little more control” was preferable than going to the hospital.

On the drive back into the city though, the imaging center called and told them to go straight to the hospital — the CT had revealed a large mass that turned out to be a germ-cell tumor.

Fortunately, Centeno’s cancer is now in remission, his wife says. But their online shopping cost them more money than if they’d gone straight to the hospital initially. The hospital gave them charity care. And although Beck took along a CD of the scans Centeno had bought online, the hospital ended up taking its own scans as well.

“You’re trying to cut costs by getting a CT out of the hospital,” Beck says. “But they’re just going to redo it anyway.”

Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent, nonprofit program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.