Why Democratic Presidential Candidates Are Eager To Talk About Health Care

Democratic candidates are offering competing visions for how to tweak or overhaul the nation’s health care system ahead of this week’s presidential debate.

Democratic candidates are offering competing visions for how to tweak or overhaul the nation’s health care system ahead of this week’s presidential debate.

Two boxing deaths in one week, a preview of Olympic swimming, and a check-in about the WNBA: Host Scott Simon gets an update from NPR sports correspondent Tom Goldman.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

And now it’s time for sports.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

SIMON: Swim records fall in Korea. The WNBA season reaches its halfway mark with today’s All-Star Game. And twin tragedies in the grisly business of boxing. NPR’s Tom Goldman joins us. Tom, thanks for being with us.

TOM GOLDMAN, BYLINE: Thank you, Scott.

SIMON: Not one, even, but two boxing deaths this week.

GOLDMAN: Yeah. Russian Maxim Dadashev and Argentine Hugo Santillan both died from brain injuries a few days after their fights last weekend. Certainly not the first boxing deaths, but being so close together – just two days apart – that’s very dramatic and has the boxing world split once again between those calling for reform and those saying, it’s tragic, but it’s just part of the game.

SIMON: You and I have both reported on the human damage in boxing over the years, and I daresay it’s one of the reasons we don’t talk about it a lot here. We – you know, we both recoil at this sometimes really being called a sport, and you and I love sports. We often talk about what boxing should do. Is there something fans can do to make it less destructive?

GOLDMAN: You know, I suppose they can take their money out of the sport. As long as there’s demand, boxing will continue and not see a need to change. But if fans stop betting, if they stop buying pay-per-view, stop attending fights and let the powers that be know this is a protest, maybe that would spur the kind of reform that might help reducing the length of fights, zero tolerance of performance-enhancing drugs, which there isn’t now, ringside doctors with neurological and concussion training at all fights and ensuring boxers train safely. Brain injuries may happen initially in training and not be detected by the time they fight.

But, you know, Scott, even if meaningful reform happens, death happens too. You know, it’s the nature of a sport where the goal is to hit someone to the point of unconsciousness. And in the words of Hall of Fame boxing writer Nigel Collins, it’s up to each of us to face that reality and decide whether or not it’s worth the price.

SIMON: Yeah. Las Vegas this afternoon, the WNBA All-Star Game means the women’s basketball season’s halfway through. What teams have been most successful so far?

GOLDMAN: Well, it’s been a very competitive season so far, led by Connecticut and Las Vegas, both with 13 and six records, but not leading by much. Eight of the 12 WNBA teams go to the playoffs. And the eighth team, Minnesota, is only three and a half games out of first place. The contenders include defending champion Seattle, which lost league most valuable player Breanna Stewart and star Sue Bird before the season to injuries. There were predictions of doom, but the Storm have stayed together. They’ve played well, and they’re in the thick of the race right now.

SIMON: And, Tom, we’re a year out from the 2020 Olympics.

GOLDMAN: Yeah.

SIMON: The World Swimming Championships are – I know you’ve just begun to pack – World Swimming Championships are taking place in South Korea right now. What might we see in these championships that can help us look forward to next year in Tokyo?

GOLDMAN: Well, you know, it might be a good preview, although Americans hope not too much of a preview for super swimmer Katie Ledecky. She’s had a really tough time of it in South Korea. Illness forced her to drop out of two events. But just today, Scott…

SIMON: Yeah.

GOLDMAN: …Some redemption.

SIMON: I saw.

GOLDMAN: Yeah, she won the 800-meter freestyle for the fourth straight time, a four-peat, at the World Championships. And for those who love controversy, there’s been plenty of that related to China’s Sun Yang. There are strong doping suspicions about him. He served a drug ban five years ago. And fellow swimmers haven’t been shy about speaking or acting out.

Competitors who won medals in races he won refused to stand on the victory stand with him. And after he won the 200-meter freestyle, British swimmer Duncan Scott, who tied for third, wouldn’t have his picture taken with Sun as they left the stage. Sun turned around and called Scott a loser and said he, Sun, was a winner. Now, Scott, whether this all plays out at the Olympics depends on an upcoming hearing where Sun could get a lifetime…

SIMON: That – I mean, this is, like, really dramatic. Who wouldn’t watch this?

GOLDMAN: (Laughter) Well, he could get a lifetime ban, though, for a strange incident with drug testers who showed up to give him a drug test, but he reportedly destroyed blood samples with a hammer…

SIMON: Yeah.

GOLDMAN: …That he’d given to those testers. So we’ll see if that plays out in Tokyo.

SIMON: Well, that gets the job done. NPR’s Tom Goldman. Thanks.

GOLDMAN: (Laughter).

SIMON: What do you think we do with – they do with our interviews? NPR’s Tom Goldman, thanks so much.

GOLDMAN: (Laughter) You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Before the men cycle across the finish line at the Tour de France, a group of women riders will finish the route. Host Scott Simon talks with Sara Beck, a member of the InternationElles team.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Tomorrow dozens of men will bike across the finish line at the Tour de France. Today women who biked that same grueling route will arrive on the Champs-Elysees, but there’ll be less fanfare – maybe. Since 2015, a group of French women have been cycling the Tour de France route one day ahead of the professional competitors. This year, they were joined by the InternationElles. That’s E-L-L-E-S. The team consists of 10 riders from three continents, and we’re joined by the one American cyclist, Sara Beck. She’s a scientist who was completing her postdoctoral studies in Switzerland.

Almost Dr. Beck, thanks so much for being with us.

SARA BECK: Hi. Thank you, Scott. Actually, I am Dr. Beck now.

SIMON: You are Dr. Beck?

BECK: That’s right.

SIMON: Well, Dr. Beck, thanks so much. Where are you speaking from, may I ask?

BECK: I am speaking from Albertville, France. So this is where we started Stage 20 of the Tour de France this morning, and this is where we’re stopping for dinner on the way back.

SIMON: Yeah. Must be hungry, huh?

BECK: Exactly. We eat quite a lot.

SIMON: You’re not a professional cyclist, but you are very dedicated, aren’t you?

BECK: Absolutely. So everyone on our team, we’re all amateur cyclists, not professionals. Many of us are racers and, some, just hobby cyclists, or weekend warriors, I like to say.

SIMON: You’re a former NASA flight controller, I gather.

BECK: That’s right.

SIMON: So what makes you want to do this for 20 – how many days?

BECK: Yes. So the cycling is 21 days. It’s the same course as the men are riding, the professional men. And I think everyone on our team, we’re all driven both by the inequality part of it and also by the personal goal part of it.

SIMON: Well, let me ask you to talk about that because there used to be a woman’s Tour de France, didn’t there?

BECK: There did. That’s right. So back in 1955, actually, there was a women’s Tour de France. There was a five-day stage race for women. And now we’re in 2019, and there’s no stage race for women. And I think that’s kind of insane, honestly. I feel like we’re going backwards. So what we have now, we have the men’s course, obviously. Everyone has heard about it. Even if you’re not interested in cycling, you know about the men’s Tour de France. And it’s a 21-day stage race, 3,460 kilometers, which is 2,100 miles all over France. And then what the women have is, they have a one-day course. And I just think that that’s unfair.

SIMON: You mentioned the 1955 attempt. They also tried to have a women’s Tour de France in the 1980s, didn’t they?

BECK: That’s right. They did. They did it, and it stopped. But just even as we’ve been riding, we heard that ASO, the organization that hosts the men’s Tour de France, that they are considering hosting a race, a stage race, for women, as well. So we feel like the message is being heard.

SIMON: Dr. Beck, it’s hot, right?

BECK: It is hot. Oh, my gosh. I don’t know how long the tour can stay in July, honestly, because this year, we were riding in temperatures above a hundred degrees. There was, just a couple days ago, a flat stage around Nimes, France, and, oh, my gosh, we were melting. It was so hot. Yes.

SIMON: Yeah. Well, what keeps you going?

BECK: I think what keeps me going is knowing that we’re inspiring people. And a lot of times along the course, you see people come out. And they’re cheering for us, and they’re excited for us. And they’re standing there with their kids. And you see little girls are watching. And you know that you’re either inspiring them, or you’re normalizing cycling. You’re saying, hey, women can do these epic endurance rides, too. And just knowing that we’re inspiring people. And even friends of mine have told me, hey, you convinced me to get back on my bike, or I signed up for this race because of you. That’s what keeps me going.

SIMON: Have you seen B.J. Leiderman, who writes our theme music, along the route?

BECK: No, I haven’t. Is she riding, as well?

SIMON: It’s a he, but yes. No. (Laughter). Well, any goody bags or medals at the end of the race?

BECK: I think there will definitely be some fanfare. I know in my case, some of my family has flown over from the U.S., and I hear that they have flags and T-shirts, and I know there will be cameras. I think everyone’s looking forward to seeing their families at the end. And we have plenty of champagne. And we’ll have a great big party. So there will definitely be enough fanfare for us.

SIMON: I mean, to go down the Champs-Elysees, that’s something, isn’t it?

BECK: Exactly. Exactly, and that’s what I play over and over in my mind when – I just get so excited at that thought. It’s really amazing to be a part of this.

SIMON: Doctor and cyclist Sara Beck, joining us from France. May the wind be at your back.

BECK: Thank you very much.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Altovise Ewing, who has a doctorate in human genetics and counseling, now works as a genetic counselor and researcher at 23andMe, one of the largest direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies, based in Mountain View, Calif.

Karen Santos for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Santos for NPR

Altovise Ewing was a senior at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tenn., when she first learned what a genetic counselor was. Although she had a strong interest in research, she suspected working in a lab wasn’t for her — not enough social interaction.

Then, when a genetic counselor came to her class as a guest lecturer, Ewing had what she recalls as a “lightbulb moment.” Genetic counseling, she realized, would allow her to be immersed in the science but also interact with patients. And maybe, she thought, she’d be able to help address racial health disparities, too.

That was 15 years ago. Ewing, who went on to earn a doctorate in Genetics and Human Genetics/Genetic Counseling from Howard University, now works as a genetic counselor for 23andMe, one of the largest direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies. As a black woman, Ewing is also a rarity in her profession.

Genetic counselors work with patients to decide when genetic testing is appropriate, interpret any test results and counsel patients on the ways hereditary diseases might impact them or their families. According to data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of genetic counselors is expected to grow by 29% between 2016 and 2026, compared with 7% average growth rate for all occupations.

23andMe’s Ewing says the lack of ethnic diversity among genetic counselors in the U.S. reduces some people’s willingness to participate in clinical trials, “because they’re not able to connect with the counselor or the scientist involved in the research initiative.”

Karen Santos for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Santos for NPR

However, despite the field’s rapid growth, the number of African Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans working as genetic counselors has remained low.

As genetics’ role in medicine expands, diversity among providers is crucial, say people working in the field. “It is well documented that people want medical services from people who look like them, and genetic counseling is not an exception,” says Barbara Harrison, an assistant professor and genetic counselor at Howard University.

Ana Sarmiento, who wrote her master’s thesis on the importance of diversity among genetic counselors, has seen this firsthand.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen the look of relief on a Spanish-speaking patient’s face when they realize they can communicate with me,” says Sarmiento, a recent graduate of Brandeis University’s genetic counseling program. “It’s what keeps me passionate about being a genetic counselor.”

Ethnic and gender diversity among providers can also increase the depth and scope of information patients are willing to share in the clinical settings — information that’s important to their health.

“In my opinion,” says Erica Price, who just received her master’s in genetic counseling from Arcadia University, “no one fights for the black community the way other black people do. I encounter a lot of other African Americans who don’t know what genetic counseling is. But when they find out that I’m a genetic counselor, they will give me their entire family medical history.”

Bryana Rivers, who is African American, recently graduated from the University of Cincinnati’s genetic counseling program, and wrote last year about her experience with a black mother whose two children had undergone extensive genetic testing to try to determine the cause of their developmental delays.

Having a firm diagnosis, the mother explained to Rivers, could help the children get access to the resources they needed in school. The mom wanted to know if the genetic variant that had been identified in her children — one that geneticists had decided was a “variant of unknown significance” — had been observed in other black families.

That question, which she hadn’t brought up in earlier discussions with health providers who weren’t African American, led to a broader, candid discussion of what these unknown variants mean and don’t mean, and why they are more common among members of understudied minorities.

“I cannot stress enough how important it is for patients to feel comfortable, to feel heard, and to know that they will not be ignored or discriminated against by their providers based on the color of their skin,” Rivers wrote in her blog post.

“I don’t want to suggest that a genetic counselor who wasn’t black wouldn’t have listened to her, but there are factors outside of what we do and say that can have an impact on our patients. Just the fact that she was able to lower her guard a bit because we share the same racial background as her speaks volumes.”

In an interview Rivers also recounted a recent session conducted by a white female genetic counselor that Rivers was shadowing that day. The patient, who was a black woman, addressed all of her answers to Rivers, although Rivers’ official role was to merely observe the appointment.

“I do feel a responsibility as a black provider to look out for my black patients and make sure they are receiving the appropriate care,” Rivers says. “Not everyone is willing to go that extra mile, and they may be more dismissive of the concerns of black patients and may not actually hear them.”

Ewing, who also conducts research, adds that the lack of diversity among genetic counselors has had a negative impact on research.

“The lack of diversity has an effect on the willingness of minorities to pursue clinical trials, because they’re not able to connect with the counselor or the scientist involved in the research initiative,” she explains. “We are now in the era of precision and personalized medicine and we need people who are comfortable talking about genetic and genomic information with people from all walks of life, so that we’re reaching all demographics.”

Since 1992, the National Society of Genetic Counselors, the largest professional organization for genetic counselors in the United States, has conducted an annual survey on the demographics of its members. Between 1992 and 2006, non-Hispanic white genetic counselors made up 91 to 94.2% of the NSGC’s membership.

In 2019, 90% of survey respondents identified as Caucasian, while only 1% of respondents identified as Black or African-American. Just over 2% of respondents identified as Hispanic, 0.4% identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native.

Some genetic counselors cite a lack of awareness among underrepresented minorities of genetic counseling as a profession as a major barrier to diversity in the field. Rivers says she had little exposure to genetic counseling as a future career path while enrolled as a biology major at the University of Maryland.

“My university stressed medical school, nursing school, or a Ph.D. in the biological sciences,” Rivers recalls. “I only had one professor in four years bring up genetic counseling.”

Samiento concurs. “You don’t have 6-year-olds running around saying ‘I want to be a genetic counselor’ — because it’s not a high visibility profession,” she says. “There are also very few minority professionals in the training programs and it takes a brave minority to look at the sea of white female faces and say ‘yes I can fit in here.’ “

“Genetic counseling is still a relatively new profession and there hasn’t been enough time and exposure for people to view [the field] the way they view other medical professions,” says Price. “People have asked me why I would pursue genetic counseling when I could be a physician assistant or a nurse or go to medical school.”

After Price’s acceptance to graduate school, one of her undergraduate professors questioned her chosen career path. “She said to me, ‘You’re a black woman in the sciences. We could have gotten you into a Ph.D. program or something where you’re making more money.’ “

As a part of its strategic plan for the years 2019-2021, the NSGC has identified diversity and inclusion as one of its four areas of strategic focus. Specific plans include developing mechanisms to highlight genetic counseling as a career in hard-to-reach communities by the end of the year. Erica Ramos, who is the immediate past president of the NSGC and serves as the board liaison to the task force, says she is optimistic that the numbers of underrepresented minorities in the field will improve.

“People in the profession have realized that we have blinders on,” she says. “But as an organization, the NSGC has been asking questions about how we can improve on diversity and be supportive of existing minority genetic counselors. We had 100 people apply to serve on the task force.”

A number of genetic counselors from diverse backgrounds have also come together to form their own support and advocacy networks. In November 2018, the Minority Genetic Professionals Network was formed to provide a forum for genetic counselors from diverse backgrounds to connect with one another.

Erika Stallings is an attorney and freelance writer based in New York City. Her work focuses on health care disparities, with a focus on breast cancer and genetics. Find her on Twitter: @quidditch424.

NPR’s Ari Shapiro talks with Damian McCall of the Agence France Presse to give us the latest developments from the Tour de France after a stage of the race was cancelled due to extreme weather.

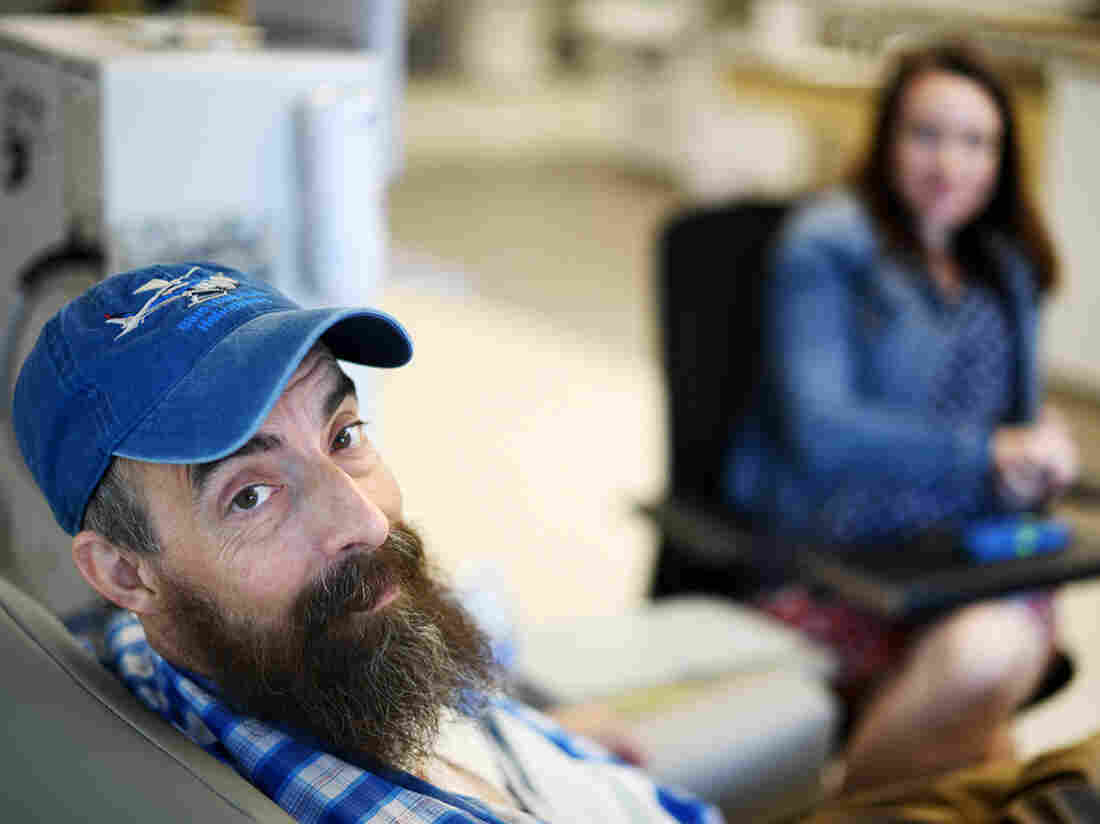

Sovereign Valentine, a personal trainer in Plains, Mont., needs dialysis for his end-stage renal disease. When he first started dialysis treatments, Fresenius Kidney Care clinic in Missoula charged $13,867.74 per session, or about 59 times the $235 Medicare pays for a dialysis session.

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

Fresenius, one of the two largest dialysis providers in the U.S., has agreed to waive a $524,600.17 bill for a man who received 14 weeks of dialysis at a clinic in Montana.

NPR, Kaiser Health News, and CBS This Morning told Sovereign Valentine’s story this week, as part of the “Bill of the Month” series, a crowdsourced investigation that seeks to understand the exorbitant health care bills faced by ordinary Americans.

On Thursday, a representative from Fresenius told Sovereign’s wife, Dr. Jessica Valentine, that the company would waive their unpaid bill. Instead, they will be treated as in-network patients, and Fresenius will seek to negotiate with their insurer a rate higher than what the insurer has already paid. The Valentines are responsible only for their $5,000 deductible, which Sovereign, who goes by “Sov,” has already hit for the year. That leaves them with $0 left to pay on their in-network deductible.

“It’s a huge relief,” Sov said. “It allows me to put more energy back into just taking care of my health and not having stress hormones raging.” Sov said he hopes his experience will shed light on the problem of balance billing and help other patients in similar situations.

A 50-year-old personal trainer, Sov was diagnosed with kidney failure in January and sent for dialysis at a Fresenius clinic 70 miles from his home in rural Plains, Mont. A few days later, Sov and Jessica learned that the clinic was out-of-network and that they would be required to pay whatever their insurer didn’t cover.

The Valentines initially could not find an in-network option, and Sov needed dialysis three times a week to survive. After he underwent 14 weeks of dialysis with Fresenius, the couple received a bill for $540,841.90. Their insurer, Allegiance, paid $16,241.73, about twice what Medicare would have paid. Fresenius billed the couple the unpaid balance of $524,600.17 — an amount that is more than the typical cost of a kidney transplant.

Fresenius charged the Valentines $13,867.74 per dialysis session, or about 59 times the $235 Medicare pays for a dialysis session.

Fresenius spokesman Brad Puffer said that the Valentines should always have been treated as in-network patients because their insurer, Allegiance, is a subsidiary of Cigna, which has a contract with the dialysis company. Under this contract, Fresenius would have been paid a higher rate than what Allegiance paid. The Valentines, he said, were caught in the middle of a contract dispute between the companies.

“In the future, we pledge to better identify situations where we believe the insurer has incorrectly classified one of our facilities as being out of network,” Puffer said in a statement. “This will allow us to address the matter directly with the insurer in the first instance, without them placing the patient in the middle.”

Allegiance declined to comment for this story. Jessica Valentine questioned whether they may owe an out-of-network deductible and is waiting to hear what her insurer says about that.

Like her husband, Jessica is relieved that their bill seems to be resolved but worried that other people with bills like theirs might not be so lucky. She’s also grateful for all the attention their story has garnered. Montana Sen. Jon Tester’s office and their hospital’s insurance broker both offered to advocate for them. “And a nephrologist from Pennsylvania called me at work and expressed outrage and said she forwarded on our story to the medical director of Fresenius on our behalf,” Jessica wrote in an email.

Now that his bill has been resolved, Sov said he’ll be focusing on the next step in battling his kidney disease: a transplant. “I can just save my energy for that,” he said.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by NPR and Kaiser Health News that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

Computer illustration of malignant B-cell lymphocytes seen in Burkitt’s lymphoma, the most common childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

It’s one of the great achievements of oncology: with advances in treatment, cure rates for children with cancer in North America now exceed 80%, up from 10% in the 1960s.

Yet for kids across the developing world, the fruits of that progress remain largely out of reach. In low- and middle-income countries, restrictive access to affordable treatment, a shortage of cancer specialists and late diagnosis dooms more than 80% of pediatric patients to die of the same illnesses.

That’s one measure of what’s known as the “global cancer divide“— the vast and growing gap in access to quality cancer care between wealthy and poorer countries, and the suffering and death that occurs disproportionately in the latter.

Nowhere is that divide more pronounced than among children, and it’s driven in large part, experts say, by perceptions of pediatric cancer care as too costly and too complicated to deliver in low-resource settings. Those assumptions, they say, prevent policymakers from even considering pediatric oncology when setting national health priorities.

But one hospital in Rwanda is rewriting that narrative.

Built and operated by the Ministry of Health and the Boston-based charity Partners In Health, the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence is unique in the region: a state-of-the-art medical facility providing the rural poor with access to comprehensive cancer care. And a new study shows that Butaro’s pediatric cancer patients can be cared for, and cured, at a fraction of the cost in high-income countries.

“There’s this myth that treating cancer is expensive,” says Christian Rusangwa, a Rwandan physician with Partners In Health who worked on the study. “And that’s because the data is almost all from high-income countries.”

Published in 2018 in the Journal of Global Oncology, the study showed that for patients at Butaro with nephroblastoma and Hodgkin lymphoma, two common childhood cancers, a full course of treatment, follow-up and social support runs as little as $1,490 and $1,140, respectively.

Much of the savings, the authors report, comes from the low cost of labor, which for the entire cancer center amounted to less than the average annual salary for one oncologist in the United States. They also cite strong partnerships with Harvard and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, whose Boston-based specialists volunteer their expertise on difficult patient cases via weekly video conferences with Butaro’s general practitioners.

“Most people don’t think about childhood cancer in terms of return on investment,” says Nickhill Bhakta, a pediatric oncologist with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, which has put in place similar partnerships with institutions in Singapore and China. “But there’s a growing body of literature showing that, for governments, treatment is surprisingly cost-effective.”

Bhakta says some of the most compelling evidence for the cost-effectiveness of care in poor countries comes from Uganda, where in March, researchers reported remarkably low costs of treating Burkitt’s lymphoma, or BL. The most common childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa, BL is rapidly fatal, often within weeks. Yet when treated promptly, intensively and with supportive care, more than 90% of children survive the disease.

Worldwide, childhood cancers are relatively rare. But as Bhakta and colleagues reported in February in The Lancet Oncology, they’re a far bigger problem than previously believed. Close to half of all children with cancer go undiagnosed and untreated, they found, suggesting that the already low survival for these cancers in low- and middle-income countries “is probably even lower.”

“The naysayers will say, ‘we don’t have pediatric oncologists in Africa, how would we possibly address this problem?’ ” says Felicia Knaul, a professor of public health at the University of Miami. “And that’s why partnership models, like those supported by Dana Farber and St. Jude, are so important — they’ve shown that you can bridge that gap and have a tremendous impact.”

In 2009, Knaul, then director of the Harvard Global Equity Initiative, led a push to expand cancer care across the developing world, where a growing burden of disease had garnered little attention globally. “We challenge the public health community’s assumption that cancers will remain untreated in poor countries,” she and colleagues wrote in a 2010 “call to action” published in The Lancet, noting “similarly unfounded arguments” against the provision of HIV treatment.

In the early 2000s, more than 20 million people were living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, yet fewer than 50,000 had access to antiretroviral therapy. Though the life-saving drugs were, by then, widely available in the U.S., skeptics warned that treatment in Africa wouldn’t be cost-effective.

Prevention, they asserted, was the only feasible way forward. “The two most important interventions are monogamy and abstinence,” Andrew Natsios, then head of the U.S. Agency for International Development, told reporters in 2001. “The best thing to do is behave yourself.”

Two decades later, echoes of that attitude reverberate in the global cancer divide; even as cancer rates continue to climb across the developing world, low and middle-income countries account for just 5% of global spending on the disease.

Still, recent years have seen important gains.

In 2017, the World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization’s decision-making body, adopted a resolution on cancer that for the first time urged its member states to address childhood cancers. And in 2018, St. Jude and the WHO launched the Global Initiative on Childhood Cancer, a five-year, $15 million partnership aimed at aimed at ensuring that all children with cancer can access high-quality medicines. Their goal: to cure at least 60% of children with the six most common types of cancer by 2030.

“Here in the U.S., it was the suffering of children with acute leukemia that drove Sidney Farber to develop our first real chemotherapy drug,” said Meg O’Brien, vice president for global cancer treatment at the American Cancer Society. “I don’t think Dr. Farber or any of the tens of thousands of oncologists, nurses or scientists who have worked in cancer research or treatment in the years since would be content to see that what we consider one of our greatest triumphs in the battle against cancer has yet to reach children in low- and middle-income countries.”

Patrick Adams is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta, GA. Find him on Twitter at @jpatadams

Credit: NPR/Shuran Huang

I was thrilled to have the gifted voice of Tamino gracing the Tiny Desk. But as charged as I was, that didn’t match the excitement that Colin Greenwood expressed as we rode up the elevator. The Radiohead bassist (and bassist for this special performance) shared a brief text exchange with his son, basically telling his hugely accomplished dad that playing the Tiny Desk was “the coolest thing he’d ever done!” That made us all smile.

The attraction that brought Colin Greenwood and these other musicians to bond with Tamino, a young singer of Belgian, Egyptian, and Lebanese descent, is his voice; it’s inescapable. For me a reference point is Jeff Buckley; they both have a way of soaring into the upper registers and into the ether; it’s stunning. I first heard Tamino perform live at a convention center in Austin; he transformed and transcended the relatively soulless space.

The songs performed at the Tiny Desk by the 22-year-old singer come from both a 2018 EP titled Habibi and later that year an album titled Amir. His use of that falsetto had some faces in the NPR audience gasping in astonishment. There’s a yearning in Tamino’s songs that I don’t often hear in popular music — he makes every vowel count. There’s nothing casual about his expressions, whether he’s singing about a sweetheart in the song “Habibi” or despair turned to joy in “Indigo Night.”

Some of the inspiration for Tamino’s approach comes from his heritage and in particular his grandfather Muharram Fouad, a well-known Egyptian singer known as “The Sound of the Nile.” It was his late grandfather’s old guitar that Tamino had first played. He got to know his grandfather’s music through his cassettes. Tamino would later incorporate what he heard into his songs. It’s ageless music that Tamino makes — it’s melodies feel well worn, but it’s also vibrant and intoxicating.

Tamino: vocals, guitar; Colin Greenwood: bass; Ruben Vanhoutte: drums; Vik Hardy: piano, vocals;

Producers: Bob Boilen, Morgan Noelle Smith; Creative Director: Bob Boilen; Audio Engineer: Josh Rogosin; Videographers: Morgan Noelle Smith, Kara Frame, Bronson Arcuri; Associate Producer: Bobby Carter; Production Assistant: Paul Georgoulis; Photo: Shuran Huang/NPR

NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly speaks with lawyer Mike Moore, who is representing several states, counties and cities that are suing opioid manufacturers.

The Atlantic League of Professional Baseball, in partnership with the major league is implementing new rules this season. It’s unclear though if these will impact the game at the highest levels.