Ireland’s Shane Lowry Wins British Open In His First Major Title

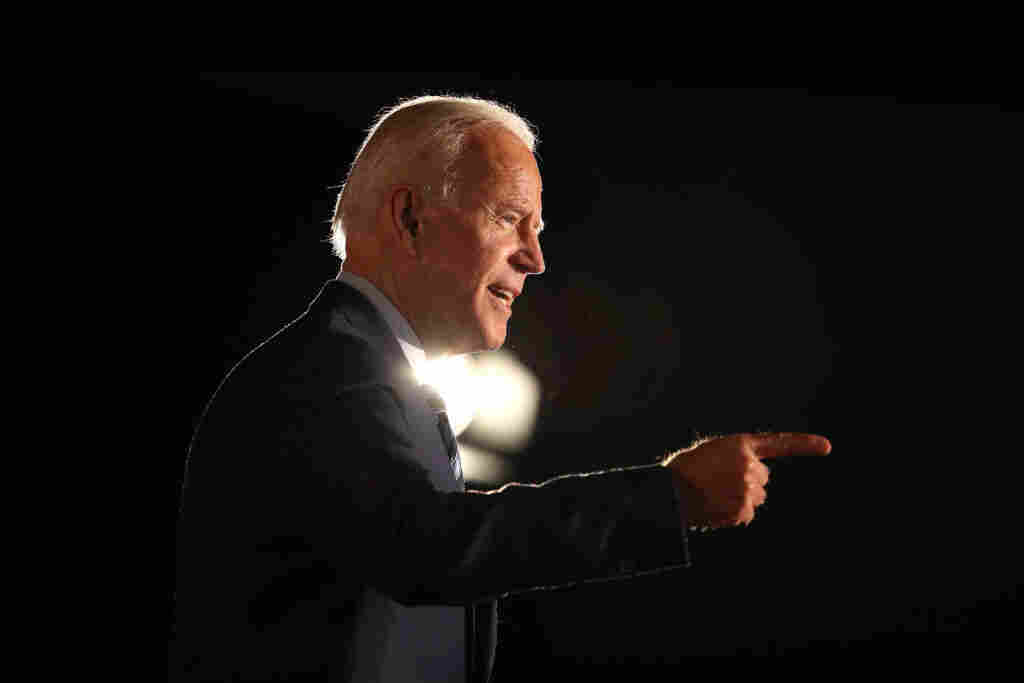

Examining Biden’s Health Care Pitch

New York Times health reporter Sarah Kliff tells NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro about Joe Biden’s health care plan and how it differs from “Medicare for All.”

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

We’re going to talk policy now – health care policy. That’s because there’s another prescription for the American health care system in the mix among the Democratic presidential field. And it doesn’t call for as sweeping a change as other plans do.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

JOE BIDEN: I understand the appeal of “Medicare for All.” But folks supporting it should be clear that it means getting rid of Obamacare. And I’m not for that.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That’s former Vice President Joe Biden announcing his plan on Monday. Let’s take a look at his idea and other plans not calling for expanding Medicare to cover everyone with Sarah Kliff. She covers health care for The New York Times. And she joins us now. Good morning.

SARAH KLIFF: Good morning.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Biden’s pitch is for Obamacare plus. What does that mean?

KLIFF: Yeah. This is a really key divide you’re seeing shape up in the Democratic field. What Biden and a number of other candidates are suggesting is something called the public option, keeping the private insurance that we have now but adding in a government-run option that is going to compete against the profit-motivated plans. And if things go as you think in theory, it will have lower premiums. People will sign up for it. And that should encourage other health care plans to lower their premiums, as well, essentially creating more competition in the private-insurance market.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Where does this fit on the spectrum of plans you’re seeing from the Democrats? I imagine you put Bernie Sanders on one end because he wants a single-payer system that eliminates private health insurance in favor of the government covering everyone. Does this put Biden squarely in the middle?

KLIFF: It’s almost to the right of the spectrum at this point, which is a really wild thing to think about, about how the public option used to be a pretty far-left position, that this is where the liberals in Congress would land. Now the left is really focused on Medicare for All, like Senator Sanders says, eliminating private health insurance, moving everyone to a government plan. The more moderate position has become, let’s build on Obamacare. Let’s add in this public option. So I almost see this as the benchmark that’s being suggested in the Democratic primary. And you wouldn’t have seen that even five, 10 years ago.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Speaking as someone who’s been reporting on health care in the U.S. for a long time now, what are the obvious advantages and disadvantages in a plan like Biden’s?

KLIFF: So I think one of the obvious advantages is that it’s a lot less of a transition, that it would be a huge, huge undertaking to move all of us onto a government health care plan and do it in four years, which is what Senator Sanders’ plan envisions, whereas the Biden plan would not be quite as disruptive. It can advertise choice. You could decide if you want private insurance, if you want the new public plan. But, you know, the things that are the advantage are the exact same things that are the disadvantage. It will not disrupt as many of the things that people don’t like about their health insurance. It won’t, for example, regulate all the health care prices in the United States, which is something the Sanders plan would do. It would probably eliminate a lot of the big surprise bills that I see a lot of my readers sending me. So the fact that it’s less disruptive – that has its advantages – also has its disadvantages, as well.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: So where is the public on this now?

KLIFF: Yeah. So they are warming up to Medicare for All, is what I would say. If you look at the trajectory of polling over the past 20 years, it’s not like there’s some groundswell of support for Medicare for All. Instead, you see a slow, steady, incremental increase in those who think it’d be a good idea for the government to provide health insurance to everybody. But what I find most interesting about the Medicare for All polling is that people really change their minds when they hear different things about it. When people learn Medicare for All would get rid of the insurance they have at work, they get much more negative. When they hear it would get rid of deductibles, they get a lot more positive. So I don’t think the country’s really made up their mind at this point. And that’s why you see this fight in the Democratic Party – is because people are trying to sell their pitch for what would be best for our health care system.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: In the 2018 election, health care became a really strong issue for the Democrats. On the other side of the aisle, what are the Republicans offering? What can President Trump bring to the table?

KLIFF: So President Trump – he does like to talk a lot about having a great, new health care plan. But we haven’t really seen the Republican Party unify around their vision of health care. We spent most of 2017 watching them try and repeal and replace Obamacare. And they were unable to come up with a plan that their caucus agreed on that could pass through Congress. Right now, Republicans are pursuing this lawsuit in Texas that would overturn the Affordable Care Act. And you’ll see Democrats talking a lot about that lawsuit – the Trump administration supporting Obamacare repeal in that particular legal battle. So, you know, you have President Trump discussing a lot of big promises for a good health care plan. You also have the Department of Justice supporting a lawsuit that would end protections for pre-existing conditions. And that’s something I think you’re going to see come up a lot as we get into the election cycle.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That’s Sarah Kliff of The New York Times, speaking via Skype. Thanks so much.

KLIFF: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Former Planned Parenthood CEO On Leadership Upheaval

NPR’s Sarah McCammon talks to Pamela Maraldo, former CEO of Planned Parenthood. She left the organization under similar circumstances as Dr. Leana Wen, who was ousted from her position this week.

Sports Roundup: Previewing Sunday’s Baseball Hall Of Fame Induction

NPR’s Scott Simon speaks with ESPN’s Howard Bryant about the 2019 baseball season so far and about Mariano Rivera, baseball’s first unanimous Hall of Famer.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Now, time for sports.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

SIMON: The 2019 baseball season heats up the summer – the first unanimous Hall of Famer – joined now by Howard Bryant of ESPN, who gets a vote in the Hall of Fame ballot. Howard, thanks so much for being with us.

HOWARD BRYANT: Good morning, Scott. How are you?

SIMON: I’m fine, thank you, sir. I saw two games at Wrigley Field this week. I’m great.

BRYANT: (Laughter).

SIMON: Three teams, now with more than 60 wins in Major League Baseball – the Yanks in the AL East, the Dodgers in the NL West, the Astros in the AL West – they’re scorching, aren’t they?

BRYANT: Yeah, they are. And once again, this is my second-favorite time of the year where you come out of the All-Star break and you start looking at teams and wondering, OK, who’s built for the entire season, and who’s going to wilt as the dog days of August commence?

And I kind of feel like these three teams are great. They’re really, really good. I mean, I – you look at the Dodgers. They’re an incredibly hungry team. They went to the World Series back-to-back years. They got beat twice. The Astros got them in 2017. The Red Sox got them last year.

You look at the Astros, who, of course, won the World Series two years ago and then, of course, the Yankees, who have been building and building for this for the last couple years. They sort of surprised everyone a couple years ago. The Red Sox got them last year. And now they are just an amazing offensive team, and they’re doing it with a lot of – well, a lot of their best players have been injured. Giancarlo Stanton isn’t even on the field right now, and the Yankees are just steamrolling everybody.

SIMON: Washington Nationals have really caught fire, too – haven’t they? – without Bryce Harper.

BRYANT: Exactly, and that’s the team that – they were, I think, 11 or 12 games under 500 earlier in the season, and now they’re in second place. They lost a tough one last night to the Braves. But I feel like this is another team that – they’ve got something to prove, as well. And especially, you’ve got those two pitchers – you’ve got Scherzer, you’ve got Strasburg – and that’s a pretty good start. I think any team in baseball would like their chances when you start the rotation with those two guys.

SIMON: And…

BRYANT: So – and let’s not forget the Twins in…

SIMON: Yep.

BRYANT: …The American League Central. And right behind them is Cleveland. There’s – and of course, the team that I used to cover, the Oakland A’s, are probably the second-hottest team in baseball. So it’s really funny, Scott. You have so many times that people talk about baseball and – oh, there’s no salary cap, and no one’s got a chance to win. And look at all of these teams that are out there who are – exactly. And by the way, they say it in that accent, as well. They say…

SIMON: I know.

BRYANT: …It just like that, right? But it’s true.

SIMON: NL Central, I just want to mention, ’cause you have a great three-way race between the Cubs…

BRYANT: And I didn’t even mention your Cubs. Exactly.

SIMON: …Who aren’t first, but the Brew Crew from Milwaukee and the Cards are close. And even the Bucs have a chance.

BRYANT: Well, and let’s not forget that last year, the Brewers were in the NLCS. So they’re close, as well. There’s a lot of teams that could win this thing, so instead of just talking about baseball being, you know, one team or two teams that can’t win – baseball actually has the most parity of all the sports.

SIMON: Baseball’s Hall of Fame abduction – abduction (laughter) – Area 51 stuff…

BRYANT: (Laughter) Baseball’s induction.

SIMON: …Induction is tomorrow. I know you get a Hall of Fame vote. Mariano Rivera, the great Yankee, is the Hall’s first unanimous inductee.

BRYANT: Indeed. And I had been withholding my vote for a couple of years because I was conflicted about steroids and conflicted about the commissioner and company inducting themselves into the Hall of Fame while allowing us the players – the voters to punish the players. And I hadn’t been a fan of that. But when it came to Rivera and also the death of Roy Halladay, I felt like I needed to vote. And so I voted this year.

And Mariano Rivera – I covered Mariano and Mike Mussina, who are both getting in. I covered both of them in the – with the Yankees in the early 2000s. And it should have happened before, but the fact that it’s Rivera – you can’t argue that. Edgar Martinez – everybody in Seattle would be very happy about that. And, Scott, you should be – what should I say? – ashamed that you’ve never been to Cooperstown. You got to go.

SIMON: Yeah. All right. Well, we’ll go together sometime. Howard Bryant of ESPN. Thanks so much.

BRYANT: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Radical or Incremental? What’s Really In Joe Biden’s Health Plan

Opponents running to Joe Biden’s left say his health plan for America merely “tinkers around the edges” of the Affordable Care Act. But a close read reveals some initiatives in Biden’s plan that are so expansive they might have trouble passing even a Congress held by Democrats.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

The headlines about presidential candidate Joe Biden’s new health care plan called it “a nod to the past” and “Affordable Care Act 2.0.” That mostly refers to the fact that the former vice president has specifically repudiated many of his Democratic rivals’ calls for a “Medicare for All” system, and instead sought to build his plan on the ACA’s framework.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, one of Biden’s opponents in the primary race and the key proponent of the Medicare for All option, has criticized Biden’s proposal, complaining that it is just “tinkering around the edges” of a broken health care system.

Still, the proposal put forward by Biden earlier this week is much more ambitious than Obamacare – and despite its incremental label, would make some very controversial changes.

“I would call it radically incremental,” says Chris Jennings, a political health strategist who worked for Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and who has consulted with several of the current Democratic candidates.

Republicans who object to other candidates’ Medicare for All plans find Biden’s alternative just as displeasing.

“No matter how much Biden wants to draw distinctions between his proposals and single-payer, his plan looks suspiciously like “SandersCare Lite,” writes former congressional aide and conservative commentator Chris Jacobs in a column for The Federalist.

Biden’s plan is built on the idea of expanding the ACA to reduce costs for patients and consumers — similar to what Hillary Clinton campaigned on in 2016. It would do things Democrats have called for repeatedly since the ACA was passed. Among Biden’s proposals is a provision that would “uncap” federal help to pay for health insurance premiums — assistance now available only to those with incomes that are 400% of the poverty level, or about $50,000 for an individual.

Under Biden’s plan, no one would be required to pay more than 8.5 percent of their income toward health insurance premiums.

But it includes several proposals that Congress has failed repeatedly to enact, including some that were part of the original debate over the ACA. Plus, Biden’s plan has some initiatives that are so expansive, it is hard to imagine them passing Congress — even if Democrats sweep the presidency and both houses of Congress in 2020.

Here are some of the more controversial pieces of the Biden health plan:

Public option

Although many of the Democratic presidential candidates have expressed varying degrees of support for a Medicare for All plan, nearly all have also endorsed creating a government-sponsored health plan, known colloquially as a “public option,” that would be available to people who buy their own health insurance. That eligible group would include anyone who doesn’t get insurance through their job or who doesn’t qualify for other government programs, like Medicare or Medicaid.

A public option was included in the version of the ACA that passed the House in 2009. But its proponents could not muster the 60 votes needed to pass that option in the Senate over GOP objections — even though the Democrats had 60 votes at the time.

Biden’s public option, however, would be available to many more people than the 20 million or so who are now in the individual insurance market. According to the document put out by the campaign, this public option also would be available to those who don’t like or can’t afford their employer insurance, and to small businesses.

Most controversial, though, is that the 2.5 million people currently ineligible for either Medicaid or private insurance subsidies because their states have chosen not to expand Medicaid would be automatically enrolled in Biden’s public option, at no cost to them or the states where they live. Also included automatically in the public option would be another 2 million people with low incomes who currently are eligible for ACA coverage subsidies – and who would also be eligible for expanded Medicaid.

That part of Biden’s proposal has prompted charges that the 14 states that have so far chosen not to expand Medicaid would save money, compared with those that have already expanded the program, because expansion states have to pay 10% of the cost of that new population.

Jennings, the Democratic health strategist, argues that extra charge to states that previously expanded Medicaid would be unavoidable under Biden’s plan, because people with low incomes in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid need coverage most. “If you’re not going to have everyone get a plan right away, you need to make sure those who are most vulnerable do,” Jennings says.

Abortion

The Biden plan calls for eliminating the “Hyde Amendment,” an annual rider to the spending bill for the Department of Health and Human Services that forbids the use of federal funds to pay for most abortions. Biden recently ran into some difficulty when his position on the Hyde ammendment was unclear.

Beyond that, Biden’s plan also directly calls for the federal government to fund some abortions. “[T]he public option will cover contraception and a woman’s constitutional right to choose,” his plan says.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act very nearly failed to become law after an intraparty fight between Democrats who supported and opposed federal funding for abortions. Abortion opponents wanted firm guarantees in permanent law that no federal funds would ever be used for abortion; abortion-rights supporters called that a deal breaker. Eventually a shaky compromise was reached.

And while it is true that there are now far fewer Democrats in Congress who oppose abortion than there were in 2010, the idea of even a Democratic-controlled Congress voting for federal abortion funding seems far-fetched. The current Democratic-led House has declined even to include a repeal of the Hyde Amendment in this year’s HHS spending bill, because it could not get through the GOP-controlled Senate or get signed by President Trump.

Undocumented immigrants

When Obama said in a speech to Congress in September 2009 that people not in the U.S. legally would be ineligible for federal help with their purchase of health insurance under the ACA, it prompted the infamous “You lie!” shout from Rep. Joe Wilson, R-S.C..

Today, all the Democratic candidates say they would provide coverage to undocumented residents. There is no mention of them specifically in the plan posted on Biden’s website, although a Biden campaign official told Politico this week that people in the U.S. who are undocumented would be able to purchase plans on the health insurance exchanges, but would not qualify for subsidies.

Still, in his speech unveiling the plan at an AARP-sponsored candidate forum in Iowa, Biden did not address this issue of immigrants’ health care. He said only that his plan would expand funding for community health centers, which serve patients regardless of their ability to pay or their immigration status, and that people in the U.S. without legal authority would be able to obtain coverage in emergencies. That is already law.

U.S. Overdose Deaths Dipped In 2018, But Some States Saw ‘Devastating’ Increases

Nationally, drug overdose deaths reached record levels in 2017, when a group protested in New York City on Overdose Awareness Day on August 31. Deaths appear to have declined slightly in 2018, based on provisional numbers, but nearly 68,000 people still died.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Good news came out from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wednesday: Preliminary data shows reported drug overdoses declined 4.2% in 2018, after rising precipitously for decades.

“It looks like this is the first turnaround since the opioid crisis began,” says Bertha Madras who served on President Trump’s opioid commission, and is a professor of psychobiology at Harvard Medical School.

She says it won’t be entirely clear until the CDC finalizes the numbers but, “I think the tide could be turning.”

But not everyone was celebrating. Some states actually saw double-digit increases.

“It’s deflating,” Rachel Winograd says. She’s an associate research professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “It’s incredibly discouraging to see the increase in Missouri in 2018 that happened at the same time as we really ramped up so many efforts to save lives and improve lives in our state.”

The provisional data shows Missouri deaths increased by 17% — one of 18 states that saw a year-over-year increase.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

Over the last several years, Missouri has received $65 million in federal grants to address the opioid crisis, Winograd says, and she has helped the state decide where and how to spend that money. They’ve focused on expanding access to medication-assisted treatment, and “saturating our communities with naloxone — the opiate overdose antidote,” she says.

“Any scholar who’s been studying this epidemic will tell you that those are effective tools at saving lives. We’ve drastically increased access to those services and we know we’ve saved thousands of lives.

“The fact that the numbers didn’t go down and that people were dying at an even higher rate — it was devastating,” Winograd says.

The numbers out Wednesday are not final, notes Farida Ahmad, mortality surveillance lead of the National Center for Health Statistics at the CDC. She says they should be close to the final numbers, though. For provisional data, “our threshold is for 90% completeness,” she says.

Michael Botticelli, the executive director of the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center and formerly President Obama’s drug czar, says the geographic variation in drug deaths is troubling.

“I think it’s important to pay attention to and really understand what is happening in each of these states, and why are some states seeing dramatic increases versus those seeing dramatic decreases?” he says.

The reasons for this geographic variation are numerous. For one, this data only reflects the difference from one year to the next, so states that had a bad year in 2017, can show an improvement in 2018, even if the overall picture is still grim.

Another variable is fentanyl, the highly potent synthetic opioid that’s been responsible for a rising number of overdoses in recent years. Some states have a lot of fentanyl in their drug supply, and others do not.

“We saw increases all along the Mississippi river, and I would not be surprised if that was due to an increase in the proportion of fentanyl in their drug supply,” Winograd says. Deaths from fentanyl continue to rise, according to Ahmad from the CDC.

Other variations in the drug supply could contribute to the differences from state to state, says Christopher Ruhm, a professor of public policy at the University of Virginia. He notes stimulants have a different geographic spread than fentanyl, and those deaths are also on the rise.

“Some of this may be due to the nature of the drug epidemic in different places, some of it may also be due to how much we are providing medication-assisted treatment, and engaging in other policies to try to address this problem,” Ruhm says.

The social safety net also plays a role, says Winograd. In Missouri, “we just have fewer resources to help people in need,” she says.

“We have a lack of housing, incarceration rates are increasing — these are all connected and making the most vulnerable people in our society at highest risk of overdose deaths.”

Missouri was among five states that showed increased overdose numbers and had not expanded Medicaid, Winograd notes. Medicaid expansion means more people have coverage for addiction treatment, and research shows it’s making a difference.

Ohio was a bright spot on the 2018 map, showing a 22% decrease in 2018, although in raw numbers, it still had 4,000 reported deaths.

“It is still a nightmare. And the danger in media over-portraying this is actually quite substantial,” says Shawn Ryan, an addiction doctor in Ohio and past-president of the Ohio Society of Addiction Medicine. “If we look at just that decrease nationally — which is not that big — we’re missing the point. In order to get back to baseline, we have a very long way to go.”

In the CDC’s preliminary national numbers, 67,744 people are reported to have died from drug overdoses in 2018. Even though that’s several thousand less than died from drug overdoses in 2017, it’s still many, many more people than died of AIDS in the worst years of the crisis.

The decline should not be a signal to slow down efforts — or funding — to combat the epidemic, Ryan says.

He cites the proposed CARE Act, a legislative effort led by Senator Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Representative Elijah E. Cummings, D-Md., which would allocate $100 billion over 10 years for addiction and recovery services. The CARE Act is modeled on the Ryan White Act, put in place to combat the AIDS epidemic.

“That’s actually much more in line with what’s needed,” says Ryan.

$100 billion would dwarf past federal funds for the epidemic. Grants from the State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis program, authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act, totaled $1 billion. In 2019, State Opioid Response federal grants are set to total $1.4 billion.

“If you look at the dollars spent to date, the fact that we’ve had the impact we’ve had is actually because of people being invested and working very hard for not that many dollars,” says Ryan.

Boticelli agrees that the only way to ensure the national trend continues is to adequately fund it. “We can’t look at a 5% reduction and say our work is done. I think it basically shows us that we have to redouble our efforts,” he says. “How are we going to ensure that states have the resources that they need to continue to focus energy on this epidemic?”

In a statement Wednesday, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar celebrated the decline and indicated that federal funding won’t be going away. “By no means have we declared victory against the epidemic or addiction in general. This crisis developed over two decades and it will not be solved overnight,” Azar wrote.

Rachel Winograd says for her, the increase in deaths in Missouri is an indication that there’s much more to do.

“I am very proud of what Missouri has done. I don’t think we should have done anything differently,” she says. “And I do think that we’ve been even more aggressive than many of the states that saw decreases, in terms of our focus on evidence-based solutions.

“It’s not that we did the wrong thing — it’s that we didn’t do enough of the right thing,” she adds. “And we need more sustainable funding to do that.”

Carmel Wroth contributed reporting to this story.

Frenchman Julian Alaphilippe Leads Tour De France As Race Enters Second Half

NPR’s Ari Shapiro speaks with Damian McCall, a reporter for the Agence France-Presse, about this year’s Tour de France and the Frenchman currently in the lead, Julian Alaphilippe.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice Offers A Sonic Refuge

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his Party, performing live at the WOMAD festival in 1985.

Andrew Catlin/Courtesy of Real World Records

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Catlin/Courtesy of Real World Records

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was hailed as one of the singers of the 20th century. Even now, more than 20 years after his death in 1997, there’s no dearth of opportunities to hear his work, through a combination of sheer popularity, an enormous official discography, and literally thousands of pirated versions. All in all, no one has been suffering for lack for recordings of this Pakistani vocal master of qawwali, a staggeringly beautiful and ecstatic musical form.

Live at WOMAD 1985 comes out July 26 (pre-order).

Stream Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s ‘Live At WOMAD 1985’

01Allah Ho Allah Ho

21:00

02Haq Ali Ali

25:05

03Shahbaaz Qalandar

9:03

04Biba Sada Dil Mor De

9:51

And yet, here we are, with a brand-new issue of Khan captured at his vocal prime, recorded when he was just at the precipice of becoming an international phenomenon: a midnight set recorded in 1985 at England’s WOMAD festival, which was co-founded by Peter Gabriel five years earlier to showcase international music and dance talent. It was the performance that was hailed as Khan’s first real introduction to non-South Asian audiences.

It’s a recording that has languished in the archives for 34 years. (There are some low-quality videos of this performance online, but the sound on this album release, carefully digitized and remixed, is excellent.) Whether for longtime fans or new initiates, Live at WOMAD 1985 is an album to be treasured.

A bit of background for newcomers: qawwali — whose root means “utterance” in Arabic — is a uniquely South Asian musical style. These devotional songs are, in places including Pakistan and India, a core part of Sufism — that is, the mystical branch of Islam that emphasizes a personal connection to God, and embraces the qualities of tolerance, peace, and equality as core principles. (Sufi shrines and gatherings have been targeted for violence by Muslim extremists, both in South Asia and elsewhere.) As Sufism spread from Persia and what is now Turkey to northern India some 800 years ago, its poetry and music were blended with local styles.

Considering the electrifying energy that surges through a qawwali performance, the traditional set-up is rather humble. A group of performers, referred to in English as a “party” – and all male – sit cross-legged on a rug-covered stage. The main singer is usually accompanied by one or two harmoniums to provide melodic support as well as percussion (normally, the tabla and dholak drums), while a small chorus sings and provides heartbeat-like claps.

This 1985 concert marks Khan at his most traditional. It starts out with one of Khan’s signature songs: “Allah Ho” [God Is], which is also known on other recordings as “Allah Hu” or “Allah Hoo.” It’s a hamd, or praise song, and the traditional way of opening a qawwali performance. The audience was slowly drawn in, first through the plush harmonium, beautifully played by Khan’s brother, Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan, and the constant murmur of tabla and the hand claps of the group’s chorus. Those listeners couldn’t have been prepared for what was about to erupt.

Khan — who is often reverently called by the honorific Khan Sahib — was literally born into this style: his family had been qawwals for over 600 years. He learned the family business from his father and uncles — though his father, who was primarily a Hindustani (North Indian) classical singer, dreamed that his son would become a doctor.

His first public performance came at his father’s funeral, when he was just 16 years old. There was a strong adherence to classical music in his family tradition, which you can hear in Khan’s own performances. Without question, he was on fire when he sang — lovers of soul and gospel will find much common ground here. But he was also an exemplary improviser in the Hindustani classical style, using solfege-like swara syllables to race up and down the span of his range, darting between intervals large and small, and always with an ear to the technical and emotional demands of a particular raga.

At WOMAD in 1985, Khan led his neophyte listeners through a very typical qawwali performance arc: after praising God in “Allah Ho,” the group moved to “Haq Ali,” [Ali is Truth], a song devoted to the Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law (and a figure revered by Sufis of both the Sunni and Shi’a sects); “Shabaaz Qalandar,” which honors a 13th century, Afghanistan-born Sufi master; and a more contemporary love song, “Biba Sada Dil Mor De,” which opens with the line “If you can’t remain in front of my eyes, please give me back my heart.” (This style of song, called a ghazal, can be understood as a secular love song or, more mystically, as a devotee’s love of the divine.)

In all, it was a very truncated performance — in more traditional settings, qawwali concerts can go all night — but it was enough to hook listeners in.

In a qawwali performance, the main singer is usually accompanied by one or two harmoniums to provide melodic support as well as percussion, while a small chorus sings and provides heartbeat-like claps.

Jak Kilby/Courtesy of Real World Records

hide caption

toggle caption

Jak Kilby/Courtesy of Real World Records

It’s hard to overstate what a milestone this festival was for Khan. Not long after he gave this performance at WOMAD, the Pakistani artist went on to release a string of studio albums for Peter Gabriel’s tastemaking record label, Real World. (Months after his WOMAD date, he made an excellent series of live recordings in Paris for the French label Ocora, as the late anthropologist and ethnomusicologist Adam Nayyar, a friend of Khan, detailed in a lovely remembrance that he wrote after the singer’s death; around the same time, Khan also made a string of sublime live albums in London, released by the Navras label.)

Live at WOMAD 1985 offers something else, too. It’s a 30-plus-year-old album, which means that — at least for the album’s duration – it offers a sonic refuge from the world we all presently inhabit, one that’s shadowed by decades of fear, suspicion, growing nationalism and acrimony. Not only was it made many years before the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — right after which some Pakistani immigrants to the U.S. were either deported by the government, or left the country ostensibly of their own accord — but also decades before Pakistanis in the U.S. worried about ICE raids, and a generation before racist rhetoric and heated anti-Muslim comments were part of the daily political salvos fired in the United States. Given what’s elapsed in the past three decades, it’s hard to envision a traditional, firmly Muslim artist reaching the same apex of visibility, or even popularity, in places like the U.S. or the U.K. had he emerged not in 1985, but in 2015.

In retrospect, it’s astonishing to think how beloved Khan became in such short measure. His presence in front of non-South Asian audiences lasted barely a dozen years — yet he counted among his fans Jeff Buckley, Madonna, Mick Jagger, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Eddie Vedder, with whom he recorded. Even so, pressure points around faith, identity and allegiances grew for Khan during his lifetime, and at home. He lamented the state of music, and by extension, the encroaching iron hand of a puritanical form of Islam, in his home country — a sort of fundamentalism that, if it had existed centuries earlier in South Asia, would have precluded qawwali from ever having developed in the first place.

“In Pakistan, people have an indifferent attitude towards music. There are no institutions to teach music and singing,” he told Pakistan’s Herald magazine in 1991. “[Our] people are morally confused about music. Those who want to learn or have learned are always confused and feel guilt. But to tell you the truth, classical music … is not against Islam. It is not haram [forbidden by Islamic principles].”

While his faith was rock-solid, Khan was catholic in his musical tastes; along with eventually making an array of crossover projects with European, British and North American artists, he wrote the music for and appeared in several Bollywood films, on screen or as a playback singer — the rawness smoothed out into honeyed drips of sound.

But Live at WOMAD 1985 offers pure soul — each run up and down the scale a jolt of adrenaline, each beat of the tabla drum and each handclap making the heart pound faster and louder. And this, truly, is the highest purpose of Sufi music: to bring performers and listeners alike into a state of ecstatic union with the divine. In 1993, after a concert that drew 14,000 people to New York’s Central Park, he told Time magazine: “My music is a bridge between people and God.”

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan struggled with his health for a long time, but when the end came, it came quickly. In August 1997, at just 48, he traveled from Pakistan to London for medical treatment; he was rushed straight from the airport to a hospital, where he died of a heart attack. In the 21 years since his death, a raft of younger male relatives have tried to carry Khan’s mantle, as performers of either buoyant qawwali, gauzy love songs, or treacly film tunes. But none of them have sparked the devotion of an international audience the way that Nusrat did. The Shahen-Shah, king of kings, qawwali’s brightest shining star, retains his crown.

Pumpsie Green, First Black Player On The Boston Red Sox, Dies At 85

Elijah “Pumpsie” Green was the first black player in Boston Red Sox history.

Harry L. Hall/Associated Press

hide caption

toggle caption

Harry L. Hall/Associated Press

Elijah “Pumpsie” Green was the first black player on the Boston Red Sox, the last Major League Baseball team to integrate. He died on Wednesday at the age of 85.

“Pumpsie Green occupies a special place in our history,” Red Sox principal owner John Henry said Wednesday, according to a news story from the team. “He was, by his own admission, a reluctant pioneer, but we will always remember him for his grace and perseverance in becoming our first African-American player. He paved the way for the many great Sox players of color who followed.”

Green made his major league debut in 1959, some 12 years after Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers. It happened after the Red Sox were forced to integrate by a government agency, and after Green endured a humiliating spring training period. Walter Carrington, who led the investigation that pushed the Red Sox to change, described the spring training in a piece for NPR member station WBUR:

“Unlike other major league clubs, the Sox did not insist that Green be allowed to stay in the same hotels as the rest of his teammates. He had to secure his own lodging, often miles away. He traveled through Texas with the Chicago Cubs, their barnstorming partners, who — unlike Boston — refused to bow to Southern segregationist traditions.

“Then, at the end of spring training, the Red Sox sent Green back to the minor leagues, despite sportswriters’ general praise of his performance. It was an outrage.”

Then-owner Tom Yawkey and his front office are now widely viewed as racist, and last year the Red Sox succeeded in changing the name of a street named after him in order to distance the team from its checkered history. For example, before Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers, he and two other black players were famously given a disingenuous try-out with the Red Sox. “We knew we were wasting our time,” he later said, according to The Boston Globe.

In an interview with the Red Sox released last year, Green described the period leading up to his debut at Fenway Park: “Sometimes it was difficult, sometimes it was hard, sometimes it was impossible but I stuck with it.”

After public pressure and Carrington’s investigation, the Red Sox eventually brought Green onto the team. He remembered his first game at Fenway as deeply nerve-wracking: “There was more pressure on me that night than I don’t know what. I couldn’t relax.”

The stands were packed with people who wanted to see him play. “As I was approaching home plate I got a standing ovation,” Green remembered. “He threw me a slider and I hit it, I got out in front and hit it off the Green Monster in left center field, and the crowd went crazy.”

Green played shortstop and second baseman for the Red Sox, but said later that he “never did get comfortable, never. … To me it was almost like opening night every game.”

He did praise baseball great Ted Williams as welcoming. According to the team, Williams “made a point of warming up with Green prior to games to help him feel like part of the team.”

In 1962, Green was traded to the Mets, where he played 17 games before retiring as a player from professional baseball. He returned to California, where he grew up, and worked as a high school baseball coach.

“Although Green may not have made much of a dent in the record books, his impact on the Red Sox will never be forgotten,” the Red Sox said.

“We salute the courage Pumpsie Green demonstrated 60 years ago when he became our first player of color,” Red Sox chairman Tom Werner added. “Despite the challenges he faced, he showed great resilience and took pride in wearing our uniform. He honored us by his presence. We send our deepest condolences to Pumpsie’s family and friends.”

Opioid Epidemic ‘Road Map’ Shows 76 Billion Pills Distributed Between 2006 And 2012

NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly talks with Washington Post reporter Scott Higham about federal data that shows the scope of the opioid crisis: 76 billion pills distributed between 2006 through 2012.