They Fight — Politely — For What’s Right For The World’s Girls

Activists from Girl Up. Top row from left: Valeria Colunga, Eugenie Park, Angelica Almonte, Emily Lin. Bottom row from left: Lauren Woodhouse, Winter Ashley, Zulia Martinez, Paola Moreno-Roman.

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

For Ayesha, a gender equality activist from Sierra Leone, fighting sexism means defying tradition. In her home country, girls are often married young and may be discouraged from going to school. To challenge these practices, the 19-year-old may have to stand up to a respected community leader.

“You are constantly walking on eggshells,” she says. (Plan International, which partners with Ayesha, asked that her last name not be used to protect her from backlash caused by the issues she addresses.)

She tries to find the balance between celebrating her African culture and helping other girls break away from harmful beliefs — messages that they’re not cut out for school or must fit traditional cultural definitions of femininity. Sometimes, community members see that kind of activism as a threat their way of life. But as Ayesha says, “If that’s making your girls bad, please, can I make your girls bad?”

Ayesha was one of ten young activists NPR interviewed at the Girl Up 2019 Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C., this week. Girl Up is a campaign founded by the U.N. foundation that promotes activism for 13- to 22-year-olds to work for the health, safety and education of girls.

The interviewees said it’s tough to stay involved. The girls, most of them in high school or college, feel pressure to maintain top grades while living up to their personal commitment to work for humanitarian causes. They say they have to be polite when they try to educate sexist men and boys so they don’t alienate them.

And they say they’re worn out from it all. A main theme that emerged was burnout: the physical and mental exhaustion that comes from constantly justifying their work to skeptical men.

But they’re determined to keep fighting — and find ways to de-stress (the music of Lizzo helps). Here’s what young activists are talking about this year.

What common terms do you hear in your activism that frustrate you?

Lauren Woodhouse, 18, Portland, Oregon

“Influencers.” Lauren says the term – referring to an individual with social media power — turns activism into something trendy and individualistic rather than communal. “There is fun in supporting women, but we should all recognize that any work is valuable work,” she says. “And when corporations [say that] ‘this is the influencer to follow and her feminism is our feminism,’ it’s tiring. I’m over that.”

Valeria Colunga, 18, Monterrey, Mexico

“Feminazi.” Valeria is fed up with the term because it showcases a lack of education about what feminism is. “It is tiring to have to explain it,” she says. She says many people she knows call themselves “humanists, not feminists.” So she explains that humanist and feminist “mean different things. If I have to explain it over and over again, I will do it. Because if I don’t, who will?”

Winter Ashley, 15, Gilbert, Arizona

“Young socialist.” She says she’s often seen feminism and social activism equated with socialism – especially on social media from “random, middle-aged white men [saying]: ‘you’re building a new generation of young socialists,'” she says. (And she knows that’s who’s being critical because she’s done some Facebook investigating.) “I’ve been called a young socialist in a very negative way by so many people. It’s wacky.”

Eugenie Park, 17, Bellevue, Washington

“Social justice warrior” is a term that annoys Eugenie. “When you hear the term by itself, it sounds like an empowering thing. But in reality, it’s a term that is used to minimize a lot of the work that young social justice people do” by making it seem the activists are just doing it “for a trend,” she says. That’s been discouraging for her and her friends.

When boys say you can’t do certain things, how do you react?

Hibatu, 21, Ghana

“My own brother told me when I was going to senior high school that science is not for girls and that I should pursue something much more girl-like, like the liberal arts. He told me that I am likely to be a failure or probably always be at the bottom of the class because it’s very unnatural to see girls doing so well in school. I said, that’s not true. We’ve seen other women across the continents in other places make it. And I told him, I’m going to go to school and do science, and when I finish I’m going to medical school. And I can say that I was always at the top of my class.” (Plan International, which partners with Hibatu as well as Ayesha, also asked that her last name not be used.)

Winter

“Sometimes people can be just mean, but other times they’re honestly uneducated. And we need to be able to calmly and respectfully educate someone else on why the movement [to advance women’s rights] is so important. Men are given all of the tools they need to succeed, and then women are told: ‘If you want it, make it happen.’ Like, we’re not gonna help you. And you need to give people examples of where this happens in the world and how you can see it affecting entire communities. Through education and conversation, you can at a minimum get your point across and at best, change their perspective.”

Ayesha, 19, Sierra Leone

Ayesha stresses that young activists need to remember that often people are ignorant about feminism and tied to cultural traditions like child marriage and female genital mutilation. “In this community where I come from, these [outdated ideas about gender] are things that they grew up with. So it’s not just young boys, it’s like, grown men who grew up with this norm ’cause it was drummed in their heads ever since they were little. And it’s really difficult to change someone overnight.” She says that sometimes these people are trying to be mean but often, “it’s because they really genuinely do not see [equality as] possible, because they’ve never seen it happen before. The way that you respond is what they are going to use to shape their minds. We have to constantly be able to shape this message in a language that is friendly.”

That sounds like a lot of effort and emotional labor. Do you ever burn out?

Zulia Martinez, 21, Mayagüez, Puerto Rico

A student at Wellesley College, Zulia says activist burnout is a huge problem. She’s part of an ongoing effort to convince the school to pull out of any investments in companies that sell fossil fuels. Focusing on the smaller victories gives her hope. “We had gotten so many students on board, almost the entire student body was supporting us.”

What do you do for self-care?

Ayesha

“Sometimes, as activists, you forget that you’re actually just a person. You have friends and you stress about your summer body. And you stress about your hair, and you also stress about the lives of other people. So people don’t realize that it’s difficult sometimes because you have school, and you have grades, and you have chores, and you have a family that you have to think about. And that’s why I think we really need to invest in self-care. Sometimes I tell myself just sleep well, and most importantly talk about your feelings, because this kind of work is very, very emotional.”

Paola Moreno-Roman, 29, Lima, Peru

“A lot of activists are passionate about things because we truly believe in them. But for most of us it comes from events that we went through when we were younger and that fuels and gives us energy. But I forget that there are things that we went through that we actually never addressed that we just shoved under the bed and just don’t like looking at it because it’s painful.” For her, therapy is helpful: “It goes along the lines of speaking to your friends, because if not, it can be a very lonely journey. Sometimes it just feels like you are the only one who cares. And that’s the loneliest feeling ever.”

Lauren

“Recently I got into weightlifting. It’s amazing how much more confident I feel, knowing I could start feeling different muscles that I’ve never felt before. And then I feel like I’m more physically able to defend myself and it makes me just feel like: ‘Hello, I’m here.'”

Eugenie

“I find a really big outlet for me is sports — I row crew. A lot of adolescent girls, we struggle with our body image. And something that’s really helped me is realizing that your body isn’t just there to look [socially] acceptable, societally beautiful. It’s there to serve you every day, and it’s there to pull you through a finish line. It’s there to carry you every day.”

From left, Edman Ali and Naima Yusuf, both 14, listen to a panel at the Girl Up 2019 Leadership Summit.

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

Who’s a musical artist that keeps you inspired and energized?

Ayesha

“Beyoncé.”

Angelica Almonte, 18, Long Island, New York

“I think Lizzo is so good.”

Hibatu

“Ariana Grande!”

Emily Lin, 16, Taipei, Taiwan

“I really like Lorde and Alessia Cara. She’s like, my hero. Or she-ro.”

Speaking of “she-roes,” who are yours?

Lauren

“Ayanna Pressley was just here [at the conference.] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, she’s like the one.”

Hibatu

“Marie Curie.”

Ayesha

“There’s a female writer, her name is Chimananda [Ngozi Adichie, Nigerian author and feminist]. I’m slightly, SLIGHTLY obsessed. I love how she balances her work with everything else that she does. I’m so in love with her.”

Angelica

“This one definitely feels a little basic, but Michelle Obama. Once I saw a picture of her [at] her great-great-great-grandmother’s tombstone.” That ancestor was a slave — “and one of her descendants becoming the first lady of the United States. That shook me.”

Zulia

“My mom. She sacrificed her career for me, and she’s the one who wanted me to become an activist. The women that surround us, empower us. And I think that’s why a lot of us have become activists.”

Valeria

“I think my girl here will be Sor Juana [Inés de la Cruz]; she’s a poet [and nun who lived and wrote in the 17th century]. She started creating poetry and art to be outspoken on issues that women were facing at that time. One specific poem talked about how men back then said that women were the ones creating their own problems. For her, it was like, how are we creating prostitution when it’s men creating demand for it? Or how do you say it’s women who are not successful when we can’t get an education?”

Any advice you have for young activists?

Winter

“One of the biggest things to remember is that activism is incredibly hard, and it takes a lot of work and a lot of perseverance. And sometimes you’ll go months without any breakthroughs. You can do all you want in the community and sometimes it’s still not going to be effective. And I think that we have to realize that that’s not a reflection of our activism. It’s not saying, oh, you’re a bad activist or what you’re doing is stupid, because it’s not. It just means that it’s going to take a little more time. And like, with myself, I am always very critical of what I’m doing; I’m not getting a breakthrough, I’m not working hard enough. And that’s not always the case. Sometimes your community isn’t ready or they’re scared of the change that you’re trying to enact. And it doesn’t happen for a really long time. Eventually, you’ll get something done. You just have to stick through.”

Luisa Torres is a AAAS Mass Media fellow at NPR. Susie Neilson is NPR’s Science Desk intern. Follow them on Twitter here: @luisatorresduq and @susieneilson

Car Shopping, Handbags And Wealthy Uncles: The Quest To Explain High Drug Prices

The Trump administration has suggested buying a prescription drug is like buying a car — with plenty of room to negotiate down from the sticker price. But drug pricing analysts say the analogy doesn’t work.

tomeng/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

tomeng/Getty Images

High drug prices are a hot topic in politics right now. President Trump has made lowering them a cornerstone of his re-election bid and is pushing a variety of ideas to get that done.

But politicians — of either party — who want to rally the public around this have a challenge: Drug pricing is incredibly complex and convoluted. Just explaining what it is — let alone how to fix it — is really hard.

You know what’s great for understanding complicated things? Analogies.

How about: My love for you is like drug list prices — sky high and arbitrary.

No?

OK, here’s a favorite of Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar: Drug list prices are like car sticker prices.

Azar is a former pharma executive, and currently the man in charge of executing Trump’s proposals to lower drug prices.

“Since 1958, car companies have been required to post their sticker prices,” he said in a speech last fall. “People still get discounts when they go to purchase a car, but sticker prices are considered an important piece of needed consumer information. There is no reason it should be any different for drugs.”

I spoke to four drug pricing experts from all over the country and nobody liked the car sticker price analogy. In terms of transparency, the comparison fits — knowing a base price is certainly useful. But it overstates the usefulness of that knowledge by implying that patients have much more power to act — to shop around or negotiate — than they actually do.

To begin with: “You’re not going to die if you don’t have a car,” says Erin Fox, a pharmacist who studies drug shortages at University of Utah Health. “But you could probably die if you don’t have your insulin.”

Prospective car buyers could always bicycle or take the bus. If they don’t like a deal, they can walk away, or try to haggle.

“When you go to the pharmacy you’re not negotiating with the pharmacist for the cost of your drugs,” says Adrienne Faerber, a lecturer at the Dartmouth Institute.

Then there’s the markup.

“When Chevy marks up the price of their car, maybe they’re marking it up 10%, or something like that, but many of these drug prices are marked up many times over,” says Robert Laszewski, a health policy consultant. “If Chevy jacked their prices up 400%, it might be a good analogy.”

It’s true that after drugmakers put money into developing, testing and actually making a drug, they can set the list price pretty much anywhere they want — whatever the market will bear.

“The better analogy to think about the pricing of drugs would be really expensive designer handbags,” Faerber suggests. “When you buy a really expensive designer handbag — tens of thousands of dollars — the materials that go into that handbag are not reflective of the actual price. That price that you’re paying is because it’s desirable, because it has a brand that has a lot of value associated with it, and because it is an indicator of potential scarcity.”

But this analogy misses all the other steps drugs go through before you get the price you pay. There are pharmacy benefit managers or PBMs — middlemen that haggle to reduce the price — and take a cut.

Insurers pay PBMs to negotiate with drugmakers over the price, and if you’re insured, you pay a slice of that price at the pharmacy. Sometimes it’s just a flat $5 copay, but more and more people are paying a lot more.

“You might have a high deductible plan — you may not have a choice, your employer may only offer a high deductible plan,” Fox says. “You’re going to be faced with full list price of medications until you hit your deductible.

“You can’t predict if you’re going to get a chronic disease or not. You can’t predict if you’re going to need an expensive medication or not,” Fox adds. “I think that’s where these high deductible plans that force patients to pay that full list price all at once are really a disservice to patients.”

Fox and many of the others I spoke to for this story pointed out that one of the most backward parts of this system is that the people who can least afford high drug prices pay the most.

Even if you have good insurance, says Stacie Dusetzina of Vanderbilt University, you’re still paying for high drug prices indirectly.

“People tend to not really think about the premiums that they’re paying for their insurance plan, which is really related to what you pay at the pharmacy counter,” Dusetzina says. Your copay might be cheap, but you might be paying a lot every month for your premium.

So list price does matter to all consumers — from those with no insurance to those with the very best health plans.

No matter what, you can’t see how high those list prices you’re paying for actually are, and you can’t negotiate a better deal.

Here’s one more shot at an analogy.

“Maybe it’s a little bit more like your rich uncle buying you a car,” Dusetzina says.

So imagine that your rich uncle is the middleman, haggling over the car’s price on your behalf. He’s doing the negotiations, Dusetzina says, so the ultimate price doesn’t really matter to you, because you’re not paying for it directly. “But maybe it comes out of your inheritance in the end.”

“Not a very nice uncle!” Laszewski says, and laughs.

So — does he have any better ideas?

“I’m hard pressed to find anything in the American marketplace that comes close to this bizarre pricing system,” Laszewski says.

Not a handbag, not a car — just a weird, convoluted system that governs how Americans get their prescription drugs.

So, maybe, my love for you is like drug list prices: inexplicable.

WNBA Suspends Riquna Williams For 10 Games Over Alleged Domestic Violence

Los Angeles Sparks guard Riquna Williams (right) dribbles in a playoff game against the Washington Mystics last year.

Nick Wass/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Nick Wass/AP

Updated at 4:15 p.m. ET

The WNBA has suspended Los Angeles Sparks guard Riquna Williams for 10 games without pay over a domestic violence incident in which she allegedly attacked a former girlfriend.

Williams was arrested in April and charged with two felony counts after authorities in Florida say she punched the woman in the head and then threatened another person with a gun.

The WNBA said it launched its own investigation into the matter, including interviews with several witnesses and a consultation with domestic violence experts, before rendering the 10-game suspension, which is about a third of a regular season.

“Among other factors, the WNBA took into account the nature and seriousness of the conduct at issue, including the involvement of a firearm,” the league said in a statement.

Despite the charges, the Sparks re-signed Williams and she has been playing this season. Her suspension starts Thursday, when the Sparks take on the Dallas Wings.

The Women’s National Basketball Players Association, the union representing WNBA players, plans to file a grievance.

“We are disappointed with the league’s actions. There is an ongoing criminal proceeding and in fairness to the player, the league could have and should have awaited its completion before taking any action,” Terri Jackson, the union’s executive director, told NPR in a statement. “Riquana has not had a fair opportunity to fully defend herself.”

According to an arrest report, Williams showed up at a residence in Pahokee, Fla. where Alkeria Davis was on Dec. 6, 2018. Police say Williams tried to get in by hitting the outside door with a skateboard.

Davis came to the door and there was a struggle as Williams tried to force her way into the residence, according to the report. It says Williams managed to get inside and then punched Davis multiple times in the head and pulled her hair.

Two men spent 10 minutes attempting to break up the fight before they were able to separate the two women and get Williams outside.

At that point, according to the report, Williams walked to a blue Camaro, grabbed a gun and pointed it at one of the men, saying “You’ll get all 18” before speeding away.

Davis told deputies with the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office that she and Williams had been dating on and off for five years, but had broken up a month before the incident. She told authorities she believes Williams was jealous that Davis was not with her, according to court records.

The altercation, Davis told police, left her with a lump on the side of her head.

Williams was arrested on April 29 and charged with burglary, with assault or battery, and with aggravated assault with a deadly firearm, court records show. She pleaded not guilty and was released on a $20,000 bond. The judge ordered that she not possess any weapons and have no contact with the victims. Her next court date is Aug. 16.

Lawyer Daniel Riccardo Paige Sr., who is representing Williams, did not return a request for comment.

The WNBA said in addition to the 10-game suspension, the league will require Williams receive to counseling.

The Sparks issued a statement to NPR saying the team has fully cooperated with the league’s investigation.

“As an organization, we abhor violence of any kind and specifically take domestic violence allegations very seriously,” according to the Sparks’ statement. “We will provide whatever resources we are allowed to help Riquna learn and grow from this unfortunate situation.”

Williams’ suspension comes as the WNBA investigates another recent domestic violence case, involving Seattle Storm player Natasha Howard, who has been accused by her wife of domestic abuse.

NPR’s Tom Goldman contributed to this report.

The Thistle & Shamrock: Songs Of Tannahill

Emily Smith.

Archie MacFarlane/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Archie MacFarlane/Courtesy of the artist

Hear the music and learn about the short life of 18th century poet Robert Tannahill, who wrote in the style of Robert Burns and composed well-loved songs that are still widely sung today. We feature artists Emily Smith, The Tannahill Weavers and Rod Patterson.

Pain Meds As Public Nuisance? Oklahoma Tests A Legal Strategy For Opioid Addiction

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter begins closing statements during the opioid trial at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla., on Monday, July 15. It’s the first public trial to emerge from roughly 2,000 U.S. lawsuits aimed at holding drugmakers accountable for the nation’s opioid epidemic.

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

A global megacorporation best known for Band-Aids and baby powder may have to pay billions for its alleged role in the opioid crisis. Johnson & Johnson was the sole defendant in a closely-watched trial that wrapped up in Oklahoma state court this week, with a decision expected later this summer. The ruling in the civil case could be the first that would hold a pharmaceutical company responsible for one of the worst drug epidemics in American history.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter‘s lawsuit alleges Johnson & Johnson and its subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals helped ignite the opioid crisis with overly aggressive marketing, leading to thousands of overdose deaths over the past decade in Oklahoma alone.

The trial took place over seven weeks in the college town of Norman. Instead of a jury, a state judge heard the case.

During closing arguments Monday, Hunter called the company the “kingpin” of the opioid crisis.

“What is truly unprecedented here is the conduct of these defendants on embarking on a cunning, cynical and deceitful scheme to create the need for opioids,” Hunter said.

The state urged Judge Thad Balkman, who presided over the civil trial for seven weeks, to find Johnson & Johnson liable for creating a “public nuisance” and force the company to pay more than $17 billion over 30 years to abate the public health crisis in the state.

Driving the opioid crisis home has been a cornerstone of the Oklahoma’s lawsuit. In closing arguments Monday, one of the state’s attorneys, Brad Beckworth, cited staggering prescribing statistics in Cleveland County, where the trial took place.

“What we do have in Cleveland County is 135 prescription opioids for every adult,” Beckworth explained. “Those didn’t get here from drug cartels. They got here from one cartel: the pharmaceutical industry cartel. And the kingpin of it all is Johnson & Johnson.”

Johnson & Johnson’s attorney Larry Ottaway, rejected that idea in his closing argument, saying the company’s products, which had included the fentanyl patch Duragesic and the opioid-based pill Nucynta, were minimally used in Oklahoma.

He scoffed at the idea that physicians in the state were convinced to unnecessarily prescribe opioids due to the company’s marketing tactics.

“The FDA label clearly set forth the risk of addiction, abuse and misuse that could lead to overdose and death. Don’t tell me that doctors weren’t aware of the risks,” Ottaway said.

Defense attorney Larry Ottaway speaks for Johnson & Johnson during closing arguments. Oklahoma is asking a state judge for $17.5 billion to help pay for addiction treatment and prevention.

Sue Ogrocki/AP Photo

hide caption

toggle caption

Sue Ogrocki/AP Photo

Ottaway played video testimony from earlier in the trial, showing Oklahoma doctors who said they were not misled about the drugs’ risks before prescribing them.

“Only a company that believes its innocence would come in and defend itself against a state, but we take the challenge on because we believe we are right,” Ottaway said in his closing argument.

Johnson & Johnson fought on after settlements

Initially, Hunter’s lawsuit included Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin. In March, Purdue Pharma settled with the state for $270 million. Soon after, Hunter dropped all but one of the civil claims, including fraud, against the two remaining defendants.

Just two days before the trial began, another defendant, Teva Pharmaceuticals of Jerusalem, announced an $85 million settlement with the state. The money will be used for litigation costs and an undisclosed amount will be allocated “to abate the opioid crisis in Oklahoma,” according to a press release from Hunter’s office.

Both companies deny any wrongdoing.

The legal liability of ‘public nuisance’

Most states and more than 1,600 local and tribal governments are suing drugmakers who manufactured various kinds of opioid medications, and drug distributors. They are trying to recoup billions of dollars spent addressing the human costs of opioid addiction.

“Everyone is looking to see what’s going to happen with this case, whether it is going to be tobacco all over again, or whether it’s going to go the way the litigation against the gun-makers went,” says University of Georgia law professor Elizabeth Burch.

But the legal strategy is complicated. Unlike the tobacco industry, from which states won a landmark settlement, the makers of prescription opioids manufacture a product that serves a legitimate medical purpose, and is prescribed by highly trained physicians — a point that Johnson & Johnson’s lawyers made numerous times during the trial.

Oklahoma’s legal team based its entire case on a claim of public nuisance, which refers to actions that harm members of the public, including injury to public health. Burch says each state has its own public nuisance statute, and Oklahoma’s is very broad.

“Johnson & Johnson, in some ways, is right to raise the question: If we’re going to apply public nuisance to us, under these circumstances, what are the limits?” Burch says. “If the judge or an appellate court sides with the state, they are going to have to write a very specific ruling on why public nuisance applies to this case.”

Burch says the challenge for Oklahoma has been to tie one opioid manufacturer to all of the harms caused by the ongoing public health crisis, which includes people struggling with addiction to prescription drugs, but also those harmed by illegal street opioids, such as heroin.

University of Kentucky law professor Richard Ausness agrees that it’s difficult to pin all the problems on just one company.

“Companies do unethical or immoral things all the time, but that doesn’t make it illegal,” Ausness says.

Judge Thad Balkman listens to closing statements at the Cleveland County Courthouse. The case was a bench trial, with both sides seeking to persuade a single judge instead of a jury. Balkman is expected to issue his decision in August.

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

If the judge rules against Johnson & Johnson, Ausness says, it could compel other drug companies facing litigation to settle out of court. Conversely, a victory for the drug giant could embolden the industry in the other cases.

Earlier in the trial, the state’s expert witness, Dr. Andrew Kolodny, testified that Johnson & Johnson did more than push its own pills — until 2016, it also profited by manufacturing raw ingredients for opioids and then selling them to other companies, including Purdue, which makes Oxycontin.

“Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers have been stealing the spotlight, but Johnson & Johnson in some ways, has been even worse,” Kolodny testified.

Kolodny says that’s why the company downplayed to doctors the risks of opioids as a general class of drugs, knowing that almost any opioid prescription would benefit its bottom line.

The state’s case also focused on the role of drug sales representatives. Drue Diesselhorst was one of Johnson & Johnson’s busiest drug reps in Oklahoma. Records discussed during the trial showed she continued to call on Oklahoma doctors who had been disciplined by the state for overprescribing opioids. She even continued to meet with doctors who had patients who died from overdoses.

But Diesselhorst testified she didn’t know about the deaths, and no one ever instructed her to stop targeting those high-prescribing physicians.

“My job was to be a sales rep. My job was not to figure out the red flags,” she said on the witness stand.

The role and responsibility of doctors

Throughout the trial, Johnson & Johnson’s defense team avoided many of the broader accusations made by the state, instead focusing on the question of whether the specific opioids manufactured by the company could have caused Oklahoma’s high rates of addiction and deaths from overdose.

Johnson & Johnson’s lawyer, Larry Ottaway, argued the company’s opioid products had a smaller market share in the state compared to other pharmaceutical companies, and he stressed that the company made every effort when the drugs were tested to prevent abuse. He also pointed out that the sale of both the raw ingredients and prescription opioids themselves are heavily regulated.

“This is not a free market,” he said. “The supply is regulated by the government.”

Ottaway maintained the company was addressing the desperate medical need of people suffering from debilitating, chronic pain — using medicines regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Even Oklahoma purchases these drugs, for use in state health care services.

Next steps

Judge Thad Balkman is expected to announce a verdict in August.

If the state’s claim prevails, Johnson & Johnson could, ultimately, have to spend billions of dollars in Oklahoma helping to ease the epidemic. State attorneys are asking that the company pay $17.5 billion over 30 years, to help abate” the crisis in the state.

Balkman could choose to award the full amount, or just some portion of it, if he agrees with the state’s claim.

“You know, in some ways I think it’s the right strategy to go for the $17 billion,” Burch says. “[The state is saying] look, the statute doesn’t limit it for us, so we’re going to ask for everything we possibly can.”

In the case of a loss, Johnson & Johnson is widely expected to appeal the verdict. If Oklahoma loses, the state will appeal, Attorney General Mike Hunter said Monday.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with StateImpact Oklahoma and Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Johnny Clegg, A Uniting Voice Against Apartheid, Dies At 66

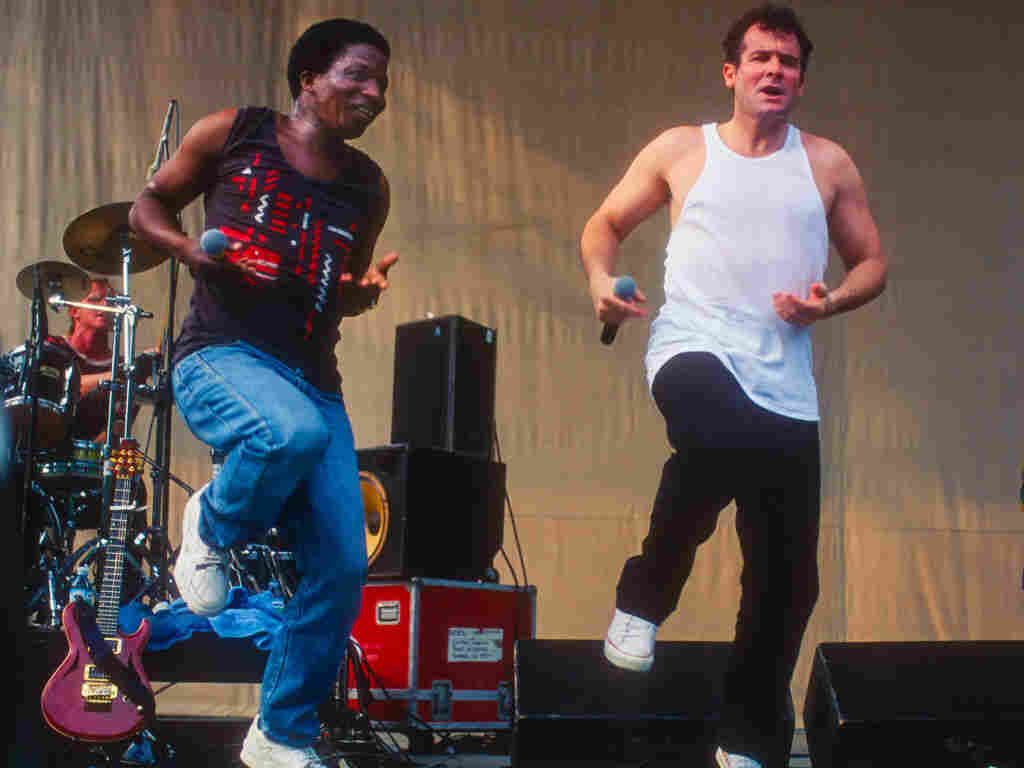

South African musician Johnny Clegg, right, with his longtime bandmate Sipho Mchunu, performing in New York City in 1996. Clegg died Tuesday at age 66.

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

One of the most celebrated voices in modern South African music has died. Singer, dancer and activist Johnny Clegg, who co-founded two groundbreaking, racially mixed bands during the apartheid era, died Tuesday in Johannesburg at age 66. He had battled pancreatic cancer since 2015.

His death was announced by his manager and family spokesperson, Roddy Quin.

Clegg wrote his 1987 song “Asimbonanga” for Nelson Mandela. It became an anthem for South Africa’s freedom fighters.

Johnny Clegg was born in England, but he became one of South Africa’s most creative and outspoken cultural figures. He moved around a lot, as a white child born to an English man and a female jazz singer from Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia). His parents split up while he was still a baby; Clegg’s mother took him to Zimbabwe before she married again, this time to a South African crime reporter, when he was 7. The family moved north to Zambia for a couple of years, and then settled in Johannesburg.

He discovered South Africa’s music when he was a young teenager in Johannesburg. He had been studying classical guitar, but chafed under its strictness and formality. When he started hearing Zulu-style guitar, he was enchanted — and liberated.

“I stumbled on Zulu street guitar music being performed by Zulu migrant workers, traditional tribesmen from the rural areas,” he told NPR in a 2017 interview. “They had taken a Western instrument that had been developed over six, seven hundred years, and reconceptualized the tuning. They changed the strings around, they developed new styles of picking, they only use the first five frets of the guitar — they developed a totally unique genre of guitar music, indigenous to South Africa. I found it quite emancipating.”

He soon found a local, black teacher — who took him into neighborhoods where whites weren’t supposed to go. He went to the migrant workers’ hostels: difficult, dangerous places where a thousand or two young men at a time struggled to survive. But on the weekends, they kicked back, entertaining each other with Zulu songs and dances.

Because Clegg was so young, he was accepted in their communities, and in those neighborhoods, he discovered his other great passion: Zulu dance, which he described as a kind of “warrior theater” with its martial-style movements of high kicks, ground stamps and pretend blows.

“The body was coded and wired — hard-wired — to carry messages about masculinity which were pretty powerful for a young, 16-year-old adolescent boy,” he observed. “They knew something about being a man, which they could communicate physically in the way that they danced and carried themselves. And I wanted to be able to do the same thing. I fell in love with it. Basically, I wanted to become a Zulu warrior. And in a very deep sense, it offered me an African identity.”

And even though he was white, he was welcomed into their ranks, despite the dangers to both him and his mentors. He was arrested multiple times for breaking the segregation laws.

“I got into trouble with the authorities, I was arrested for trespassing and for breaking the Group Areas Act,” he told NPR. “The police said, ‘You’re too young to charge. We’re taking you back to your parents.'”

He persuaded his mother to let him go back. And it was through his dance team that he met one of his longest musical collaborators: Sipho Mchunu. As a duo, they played traditional maskanda guitar music for about six or seven years.

“We couldn’t play in public,” Clegg remembered, “so we played in private venues, schools, churches, university private halls. We played a lot of embassies. We played a lot of consulates.”

Over time, they started thinking bigger; Clegg wanted to try to meld Zulu music with rock and with Celtic folk.

“I was exposed to Celtic folk music early on,” he told NPR. “I never knew my dad, and music was one way which I can connect with that country. I liked Irish, Scottish and English folk music. I had a lot of tapes and recordings of them. And my stepfather was a great fan of pipe music. On Sundays, he would play an LP of the Edinburgh Police Pipe Band.”

Clegg was sure that he heard connetions between the rural music of South Africa’s Natal province (now known as KwaZulu-Natal) — the music that he was learning from his black friends and teachers — and the sounds of Britain. So Clegg and Mchunu founded a fusion band called Juluka — “Sweat” in Zulu.

At the time, Johnny was a professor of anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg; Sipho was working as a gardener. They dreamed of getting a record deal even though they knew they couldn’t get airplay, or perform publicly in South Africa.

It was a hard sell to labels. South African radio was strictly segregated, and record companies refused to believe that an album sung partly in Zulu and partly in English would find an audience in any case. Clegg told NPR that their songs’ primary subject material wasn’t setting off any sparks with record producers, either.

“You know, ‘Who really cares about cattle? You’re singing about cattle. You know we’re in Johannesburg, dude, get your subject matter right!’ Clegg recalled. “But I was shaped by cattle culture, because all the songs I learned were about cattle, and I was interested. I was saying, ‘There’s a hidden world. And I’d like to put it on the table.'”

They got a record deal with producer Hilton Rosenthal, who released Juluka’s debut album, Universal Men, on his own label, Rhythm Safari, in 1979. And the band managed to find an audience both at home and abroad. One of its songs, “Scatterlings of Africa,” became a chart hit in the U.K.

YouTube

The band toured internationally for several years, and went. But eventually, Mchunu decided he’d had enough. He wanted to go home — not just to Johannesburg, but home to his native region of Zululand, in the KwaZulu-Natal province, to raise cattle.

“It was really hard for Sipho,” Clegg told NPR. “He was a traditional tribesman. To be in New York City, he couldn’t speak English that well — there were times when I think he felt he was on Mars. And after some grueling tours, he said to me, ‘I gave myself 15 years to make it or break it in Joburg, and then go home.’ So he resigned, and Juluka came to an end —and I was still full of the fire of music and dance.”

So Clegg founded a new group called Savuka — which means “We Have Risen” in Zulu. Savuka had ardent love songs, like the swooning “Dela,” but many of the band’s tunes, like “One (Hu)Man, One Vote” and “Warsaw 1943 (I Never Betrayed the Revolution),” were explicitly political.

“Savuka was launched basically in the state of emergency in South Africa, in 1986,” Clegg observed. “You could not ignore what was going on. The entire Savuka project was based in the South African experience and the fight for a better quality of life and freedom for all.”

Long after Nelson Mandela was freed from prison and had become president of South Africa, he danced onstage with Savuka to that song that Clegg had written for him.

YouTube

Clegg went on to a solo career. But in 2017, he announced he’d been fighting cancer. And he made one last international tour that he called his “Final Journey.”

The following year, dozens of musician friends and admirers — including Dave Matthews, Vusi Mahlasela, Peter Gabriel, and Mike Rutherford of Genesis — put together a charity single to honor Clegg. It’s benefitted primary school education in South Africa.

YouTube

Clegg never shied away from being described as a crossover artist. Instead, he embraced the concept.

“I love it,” he said. “I love the hybridization of culture, language, music, dance, choreography. If we look at the history of art, generally speaking, it is through the interaction of different communities, cultures, worldviews, ideas and concepts that invigorates styles and genres and gives them life and gives people a different angle on stuff that was really, just, you know, being passed down blindly from generation to generation.”

Johnny Clegg didn’t do anything blindly. Instead, he held a mirror up to his nation — and urged South Africa to redefine itself.

Regulations That Mandate Sepsis Care Appear To Have Worked In New York

Bacteria (purple) in the bloodstream can trigger sepsis, a life-threatening illness.

Steve Gschmeissner/ScienceSource

hide caption

toggle caption

An unusual state regulation that dictates how doctors need to treat a specific disease appears to be paying off in New York, according to a study published Tuesday.

The disease is sepsis, which is the most common cause of death in hospitals. And the regulations came into being after the story of 12-year-old Rory Staunton became a cause célèbre.

As his mother Orlaith Staunton tells it, Rory came home from school one day with a scrape he’d gotten in gym class. It didn’t seem like a big deal, but Rory’s health quickly took a turn.

“During the night I heard him throwing up and I went out and he said, ‘It’s my leg, Mom, it’s my leg.'”

His temperature spiked above 103 and he couldn’t keep anything down the next day, so she took him to their pediatrician in New York City.

The doctor decided Rory had the flu and sent him on to the hospital to get fluids. Staunton says doctors in the emergency room decided it was simply a stomach bug and sent him home. But Rory kept getting worse.

“We brought him back into hospital — that was on Friday night — and he died on Sunday evening,” Staunton says. “He went straight into intensive care when we brought him back in. And it was after he died that we were told that he had died from sepsis.”

She says she’d never heard of sepsis, even though the illness strikes more than a million Americans a year and kills more than 250,000 annually.

Sepsis is an overreaction of the body’s immune system to an infection. Common symptoms include fever, chills, difficulty breathing and an elevated heart rate.

If the hospital had diagnosed Rory correctly during his first visit and treated him aggressively, Staunton says, he likely would have lived.

She and her husband, Ciaran, “were angry and we wanted to do something that would bring about some change in how sepsis was being diagnosed and how people would know what sepsis was,” she says.

Rory Staunton, a boy from Queens, New York, whose death from sepsis at age 12 led to regulations that aimed to improve diagnosis and care.

Courtesy of Orlaith Staunton

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Orlaith Staunton

And as a result of their efforts, Rory’s death in 2012 catalyzed action in New York state, which in 2013 imposed “Rory’s Regulations,” a directive to doctors and hospitals on how to treat sepsis. The key is rapid diagnosis, a prompt jolt of antibiotics, and careful management of fluids.

Jeremy Kahn, a critical care physician at the University of Pittsburgh who also studies health policy and management, says doctors like him don’t like to be directed how to treat their patients. They prefer to follow professional guidelines. But as is surprisingly common, doctors are slow to adopt best practices. And that’s true for sepsis.

“The decades of undertreating patients with sepsis has a bit weakened our position,” Kahn says, “and it’s time to be a little, be more open about, accepting about these regulatory approaches.”

But first Kahn and his colleagues wanted see whether the New York regulations really did make a difference. Sepsis death rates are declining nationwide, so the question is whether New York’s rules led to faster improvement compared to other states.

Kahn and his colleagues compared the rate of improvement in New York to that of other states and concluded that “these regulations had their intended effect of reducing mortality,” he says. The results were published in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association.

One reason some doctors have been reluctant to embrace the regulation is that it expects them to follow a specific set of practices, including a formula regulating how much fluid to infuse and when.

“There’s a lot of concern in the clinical community that this much fluid can harm at least some patients with sepsis,” Kahn says. While the rules overall may be saving lives, this element of them may actually be counterproductive. But doctors aren’t supposed to deviate from them.

There clearly is still room for improvement in treating sepsis, so rules need to be flexible enough to embrace improvements as they emerge, Kahn says. “The evidence changes all the time,” he says, “and when you enshrine [what is currently] ‘best practice’ into laws or regulations then you become less nimble.”

Another question is whether New York’s success would be repeated elsewhere. New York state started off much worse than many other states, so it’s possible the regulations simply helped the state catch up with others, he says.

“It does call into question what kind of impact these regulations will have in other states that may have better sepsis outcomes at baseline,” Kahn says.

That matters because a few other states have similar regulations or laws, and more than a dozen more are considering them. The Stauntons started a foundation, which is now trying to push this nationwide.

Orlaith Staunton says it just won’t do to leave it to the judgment of individual doctors.

“It’s not enough to say, ‘Leave it to me and I’ll recognize it when I see it,’ ” she says. “Because clearly it has not been recognized. I think good doctors will agree that this is something that needs to be regulated.”

She hopes the new scientific results will sway some of the doctors and hospitals who are resisting a government mandate.

That won’t happen overnight. Demetrios Kyriacou, an emergency medicine physician at Northwestern University, wrote a cautionary editorial in JAMA saying that “major public health interventions cannot be based on [Kahn’s] single observational study.”

“Because demands on nurses and physicians to provide rapid intensive care to patients in critical settings can affect patient treatment,” he wrote, “any strategy aimed toward reducing sepsis-related morbidity and mortality must be based on convincing evidence before being mandated by governmental regulations.”

You can contact NPR Science Correspondent Richard Harris at rharris@npr.org.

What Did Wimbledon Teach Us About Genius?

Matthias Hangst/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt of Planet Money’s newsletter. You can sign up here.

Sunday’s tennis championship at Wimbledon between Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer lasted nearly five hours, a record. It finished with a 12-12 tie in the final set, triggering a first-to-seven tiebreaker. For tennis fans, it was an epic struggle between legends in a storybook setting. The weather was perfect, and the hats were divine. For readers of David Epstein’s new book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, however, it was an academic nail-biter, a test case in a simmering war between specialists and generalists.

Range argues that professional success in most fields is not primarily the product of intense specialization but of generalization, of the cross-pollination of ideas and experiences. Range is an ode to late starters, like Vincent van Gogh, who wandered Europe and failed at all kinds of things, including preaching, before changing the art of painting. It’s about the NASA scientists who failed to prevent the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle, because they couldn’t operate outside the discipline of their training. It extols violinists who start late and polymaths like Charles Darwin.

Epstein is also the author of The Sports Gene, about genetics and outcomes in athletics. Taken together, The Sports Gene and Range form something like a rebuttal to Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and the whole gospel of the 10,000 hours, which suggests that mastery can be achieved only through consistent, unwavering focus. (The two authors, in their own classic bout, actually spent a lecture arguing about generalization and specialization at a sports conference this year. You can watch it here.) Range, like Outliers, is a book about ideas, success and brilliance, and both books rely on zillions of academic studies.

And it’s about sports, of course, our most measured form of success, with a stop on the tennis court. The book opens with a story about Federer, who is described as the antithesis of Tiger Woods. (Epstein says he titled his book proposal Tiger vs. Roger.) Tiger Woods played nothing but golf, starting at around 2 years old. Federer, Epstein writes, was raised on a variety of sports. His mother specifically discouraged him from specializing in tennis. He was steered away from playing more competitive matches so he could hang out with his friends. His mother often didn’t even watch him play.

Increasingly, writes Epstein, research about sports in particular and many fields in general is finding that early specialization more often leads to burnout and skill mismatches than success. The better path, statistically, is early and wide “sampling.” It matches people to the best skills. It allows disciplines to inform one another. The numbers suggest this is true for most professional athletes, and, of course, we all want it to be true. Specialization is grueling, relentless and not really that charming.

But!

Djokovic won. Beat Federer at the end of five hours by one point.

And Djokovic is a specialist, in its most extreme form. There are no accounts of Djokovic dabbling, testing a bunch of different sports. A child prodigy, he picked up tennis at 4 and never strayed. At 7, he was interviewed for a television spot in Serbia. “Tennis is my job,” he said, according to Sports Illustrated. “My goal in tennis is to become No. 1.” He had no other interests.

Bummer. But, still, Range is a delight to read because it tells us what we want to learn: that aimlessness is the path to greatness, that our distractibility is not our weakness but our secret power, that genius and perfection can show up for us with luck, as long as we’re just willing to amble around enough.

And you could hear that wish in the crowd, which was cheering for the lovely-to-watch Federer. No one wants to be Djokovic, the anxiety-ridden grinder. But he does seem to win a lot.

If you’d just finished Range and were pumped to dabble, and maybe get started on greatness later, Wimbledon was a real heartbreaker.

Did you enjoy this newsletter? Well, it looks even better in your inbox! You can sign up here.

Records Show Medicare Advantage Plans Overbill Taxpayers By Billions Annually

Medicare Advantage plans, administered by private insurance firms under contract with Medicare, treat more than 22 million seniors — more than 1 in 3 people on Medicare.

Roy Scott/Ikon Images/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Roy Scott/Ikon Images/Getty Images

Health insurers that treat millions of seniors have overcharged Medicare by nearly $30 billion over the past three years alone, but federal officials say they are moving ahead with long-delayed plans to recoup at least part of the money.

Officials have known for years that some Medicare Advantage plans overbill the government by exaggerating how sick their patients are or by charging Medicare for treating serious medical conditions they cannot prove their patients have.

Getting refunds from the health plans has proved daunting, however. Officials with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services repeatedly have postponed or backed off efforts to crack down on billing abuses and mistakes by the increasingly popular Medicare Advantage health plans offered by private health insurers under contract with Medicare. Today, such plans treat more than 22 million seniors — more than 1 in 3 people on Medicare.

Now CMS is trying again, proposing a series of enhanced audits tailored to claw back $1 billion in Medicare Advantage overpayments by 2020 — just a tenth of what it estimates the plans overcharge the government in a given year.

At the same time, the Department of Health and Human Services Inspector General’s Office has launched a separate nationwide round of Medicare Advantage audits.

As in past years, such scrutiny faces an onslaught of criticism from the insurance industry, which argues the CMS audits especially are technically unsound and unfair and could jeopardize medical services for seniors.

America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group, blasted the CMS audit design when details emerged last fall, calling it “fatally flawed.”

Insurer Cigna Corp. warned in a May financial filing: “If adopted in its current form, [the audits] could have a detrimental impact” on all Medicare Advantage plans and “affect the ability of plans to deliver high quality care.”

But former Sen. Claire McCaskill, a Missouri Democrat who now works as a political analyst, says officials must move past powerful lobbying efforts. The officials must hold health insurers accountable, McCaskill says, and demand refunds for “inappropriate” billings.

“There are a lot of things that could cause Medicare to go broke,” she says. “This would be one of the contributing factors. Ten billion dollars a year is real money.”

Catching overbilling with a wider net

In the overpayment dispute, health plans want CMS to scale back, if not kill off, an enhanced audit tool that, for the first time, could force insurers to cough up millions in improper payments they’ve received.

For more than a decade, audits have been little more than an irritant to insurers, because most plans go years without being chosen for review and often pay only a few hundred thousand dollars in refunds as a consequence. When auditors uncover errors in the medical records of patients the insurers were paid to treat, CMS has simply required a rebate for those patients for just the year audited — relatively small sums for plans with thousands of members.

The latest CMS proposal would raise those stakes enormously by extrapolating error rates found in a random sample of 200 patients to the plan’s full membership — a technique expected to trigger many multimillion-dollar penalties. Though controversial, extrapolation is common in medical fraud investigations — except for investigations into Medicare Advantage. Since 2007, the industry has successfully challenged the extrapolation method and, as a result, largely avoided accountability for pervasive billing errors.

“The public has a substantial interest in the recoupment of millions of dollars of public money improperly paid to health insurers,” CMS wrote in a Federal Register notice late last year announcing its renewed attempt at using extrapolation.

Penalties in limbo

In a written response to our questions, CMS officials said the agency has already conducted 90 of those enhanced audits for payments made in 2011, 2012 and 2013 — and expects to collect $650 million in extrapolated penalties as a result.

Though that figure reflects only a minute percentage of actual losses to taxpayers from overpayments, it would be a huge escalation for CMS. Previous Medicare Advantage audits have recouped a total of about $14 million — far less than it cost to conduct them, federal records show.

Though CMS has disclosed the names of the health plans in the crossfire, it has not yet told them how much each owes, officials said. CMS declined to say when, or if, they would make the results public.

This year, CMS is starting audits for 2014 and 2015, 30 per year, targeting about 5% of the 600 plans annually.

This spring, CMS announced it would extend until the end of August the audit proposal’s public comment period, which was supposed to end in April. That could be a signal the agency might be looking more closely at industry objections.

Health care industry consultant Jessica Smith says CMS might be taking additional time to make sure the audit protocol can pass muster.

“Once they have their ducks in a row,” she says, “CMS will come back hard at the health plans. There is so much money tied to this.”

But Sean Creighton, a former senior CMS official who now advises the industry for health care consultant Avalere Health, says payment error rates have been dropping because many health plans “are trying as hard as they can to become compliant.”

Still, audits are continuing to find mistakes. The first HHS inspector general audit, released in late April, found that Missouri-based Essence Healthcare Inc. had failed to justify fees for dozens of patients it had treated for strokes or depression. Essence denied any wrongdoing but agreed it should refund $158,904 in overcharges for those patients and ferret out any other errors.

Essence also faces a pending whistleblower suit filed by Charles Rasmussen, a Branson, Mo., doctor who alleges the health plan illegally boosted profits by overstating the severity of patients’ medical conditions. Essence has called the allegations “wholly without merit” and “baseless.”

Essence started as a St. Louis physician group, then grew into a broader holding company in 2007, backed by prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist John Doerr, with his brother Thomas Doerr, a St. Louis doctor and software designer. Neither would comment for this story.

How we got here

CMS uses a billing formula called a “risk score” to pay for each Medicare Advantage member. The formula pays higher rates for sicker patients than for people in good health.

Congress approved risk scoring in 2003 to ensure that health plans did not shy away from taking sick patients who could incur higher-than-usual costs from hospitals and other medical facilities. But some insurers quickly found ways to boost risk scores — and their revenues.

In 2007, after several years of running Medicare Advantage as what one CMS official dubbed an “honor system,” the agency launched “Risk Adjustment Data Validation” audits. The idea was to cut down on the undeserved payments that cost CMS nearly $30 billion over the past three years.

The audits of 37 health plans revealed that, on average, auditors could confirm just 60% of the more than 20,000 medical conditions CMS had paid the plans to treat.

Extra payments to plans that had claimed some of its diabetic patients had complications, such problems with eyes or kidneys, were reduced or invalidated in nearly half the cases. The overpayments exceeded $10,000 a year for more than 150 patients, though health plans disputed some of the findings.

But CMS kept the findings under wraps until the Center for Public Integrity, an investigative journalism group, sued the agency under the Freedom of Information Act to make those results public.

Despite the alarming findings, CMS conducted no audits for payments made during 2008, 2009 and 2010 as they faced industry backlash over CMS’ authority to conduct them, and the threat of extrapolated repayments. Records released through the FOIA lawsuit show some inside the agency also worried that health plans would abandon the Medicare Advantage program if CMS pressed them too hard.

CMS officials resumed the audits for 2011 and expected to finish them and assess penalties by the end of 2016. That has yet to happen, amid the continuing protests from the industry. Insurers want CMS to adjust downward any extrapolated penalties to account for coding errors that exist in standard Medicare. CMS stands behind its method — at least for now.

At a minimum, argues AHIP, the health insurers association, CMS should back off extrapolation for the 90 audits for 2011-13 and apply it for 2014 and onward. Should the agency agree, CMS would write off more than half a billion dollars that could be recovered for the U.S. Treasury.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Oklahoma Opioid Trial Ends

Monday was the last day in a widely-watched trial about opioid addiction in Oklahoma. The state sued opioid manufacturers, but only Johnson & Johnson fought it in court after others settled.