How A Prenatal ‘Bootcamp’ For New Dads Helps The Whole Family

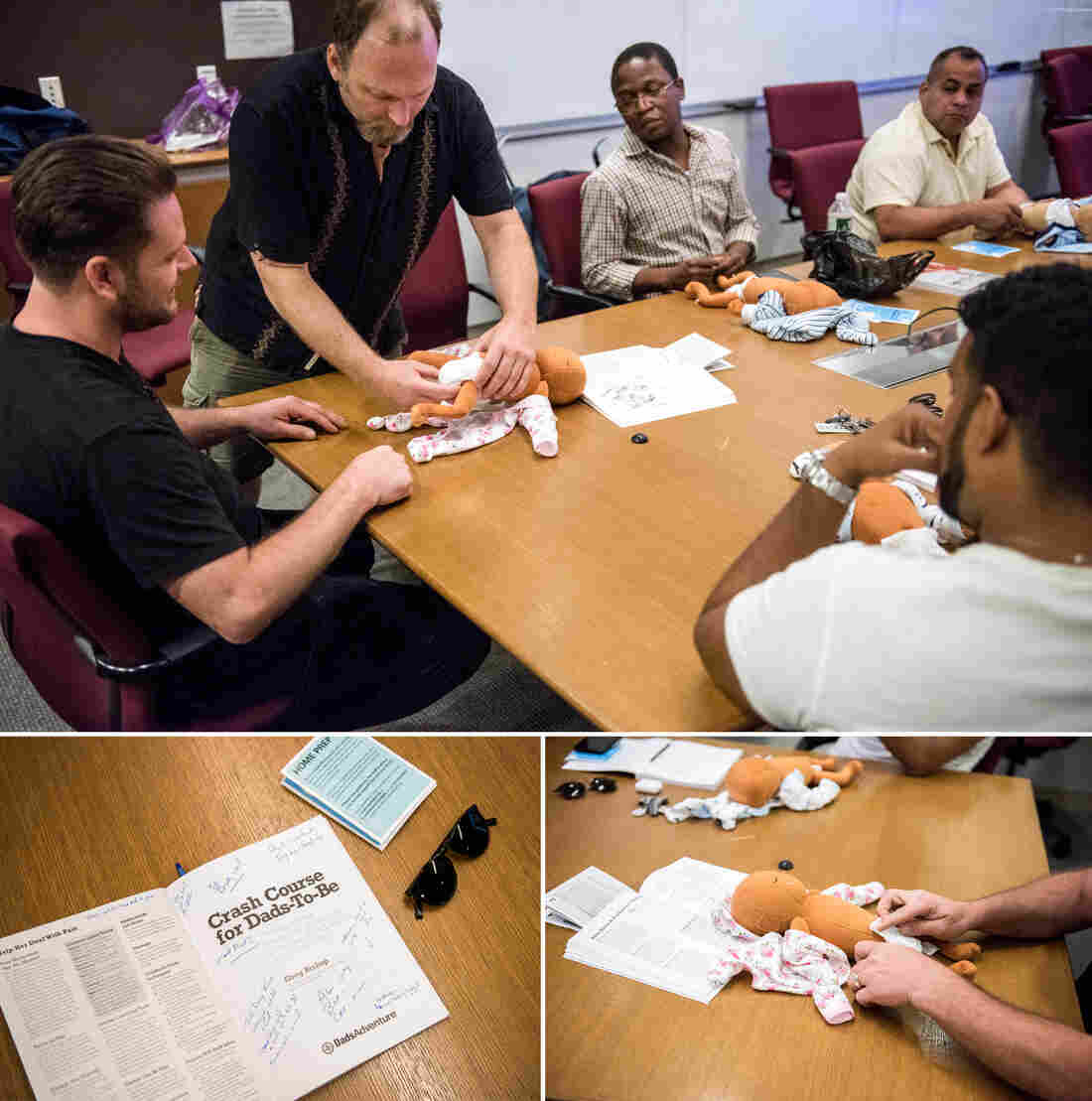

Joe Bay (center), coach of a New York City “Bootcamp for New Dads,” instructs Adewale Oshodi (left) and George Pasco in how to cradle an infant for best soothing.

Jason LeCras for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras for NPR

“Before I became a dad, the thought of struggling to soothe my crying baby terrified me,” says Yaka Oyo, 37, a new father who lives in New York City. Like many first-time parents, Oyo worried he would misread his newborn baby’s cues.

“I pictured myself pleading with my baby saying, ‘What do you want?’ “

Oyo’s anxieties are common to many first-time mothers and fathers. One reason parents-to-be sign up for prenatal classes, is to have their questions, such as ‘What’s the toughest part of parenting?’ and ‘How do I care for my newborn baby?’ answered by childcare experts.

However, though prenatal classes show both parents how to swaddle, soothe, and comfort their infants, they are usually aimed mostly at the mom — discussing her shifting role and how to cope with the bundle of emotions motherhood brings.

With that focus, “Dad’s parenting questions can fall to the wayside,” says Dr. Craig Garfield, an associate professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and an attending physician at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago. And the lack of attention to a new father’s needs can have ripple effects that impact the whole family — in the short-run and later, Garfield says.

Around the U.S., a number of health care providers, such as Garfield in Chicago and the non-profit ‘Bootcamp for New Dads’ in New York City, have begun trying to change their approach to such classes. Some go so far as to hold single-sex prenatal classes specifically for men.

“Because each parent holds a separate role in their child’s life, expectant mothers and fathers may seek different answers to their parenting questions,” Garfield explains.

Indeed, raising children is nothing new, but parenting culture has shifted in the U.S., over time. For instance, compared to parents of the 1960s, today’s mothers and fathers tend to focus more of their time and money on their children, a recent study suggests, adopting what sociologists call an “intensive parenting” style.

Parental worries about their kids’ academic success and future financial stability may drive this parenting philosophy, researchers say.

These mounting responsibilities can stress the family, which is why mothers and fathers may feel eager to define their parenting roles. While a new mother’s role in modern society is often directed by her baby’s needs to breastfeed, cuddle and sleep; a new father’s role isn’t always spelled out.

Dads-to-be learn how to change diapers in the workshop for and by men, at the New York Langone Medical Center. Participants say they appreciate the combination of concrete skills and candid advice from other fathers.

Jason LeCras for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras for NPR

“Even though fathers are far from secondary in their children’s lives, they may feel uncertain about their place in the family,” says Julian Redwood, a psychotherapist in San Francisco who counsels dads.

In fact, Garfield says, as they await their baby’s arrival, men, like women, often worry about the hands-on tasks of childcare, how to raise well-adjusted kids, and about how to cope with sleep deprivation, especially after they return to work.

Addressing those concerns early helps dads get involved with parenting from the outset, and that bolsters the whole family’s health — maybe especially the baby’s — according to research by pediatricians and child psychologists. For example, a 2017 study found that the amount of hands-on, sensitive engagement dads were observed to have with babies at age 4 months and 24 months correlated positively with the baby’s cognitive development at age 2.

Early father involvement also benefits the health of the child by fostering sturdier father-child bonds and psychological resilience, researchers say.

Oyo says the three-hour-long, Sunday Bootcamp for New Dads session he attended at NYU Langone Medical center, helped ease his early fears. At the peer-led workshop, “I learned babies communicate through crying,” he says, “and that they usually cry for four reasons — which made infant care seem less scary.”

Joe Bay, a 44-year-old father who lives in Clifton, N.J., was the session’s coach. Calling the course a “bootcamp” acknowledges the ambivalent relationship dads may feel between childcare duties and societal views of masculinity, Bay says. It also speaks to the practicality of what the men can expect to learn — how to hold a tiny baby, for example, or how to soothe a crying infant.

Participants also learn how parenthood can rock their partner’s well-being — and upend their own emotional health, as it rattles their sense of identity.

Future fathers get a chance in the course to question Bootcamp grads. Bay says he finds many fathers-to-be more willing to open up when their partners are absent. Oyo concurs.

“I met a dad who seemed like a ‘pro’ with his infant son, which was reassuring,” Oyo says. Learning from that man how to change a diaper and how to swaddle a baby, he says, helped him stay calm later, when facing his own wailing daughter. In the class he’d learned how to “read her cues.”

As the dads get more secure in their parenting skills, the moms usually become less anxious, too. And that’s crucial in making sure a behavioral tendency family scientists call “maternal gatekeeping” doesn’t derail the family system.

“Maternal gatekeeping encompasses a set of behaviors that mothers may use — consciously or unknowingly — that limit the father’s involvement with their children,” explains Anna Olsavsky, a doctoral candidate in human development and family science at The Ohio State University, and lead author of a 2019 study of how such “gatekeeping” influences a budding family.

Gatekeeping behaviors can be small but powerful: micromanaging dad’s interaction with the baby, for example, or criticizing how he holds or feeds the child.

Though fathers have always been somewhat involved in their children’s care, Olsavsky says, society still deems mothers “childcare experts.”

“That portrayal can lead dads to be socialized into supportive parenting roles” she adds — in other words, they take a step back.

In their most recent study, Olsavsky and her colleagues found that men who felt welcomed by their partners to participate in child rearing felt more connected to their partners, and were more likely to identify as equally involved and responsible co-parents.

Guests of the class Jesse Applegate (center) and his son, Jacob, field questions from Saxon Eldridge (left), and Chris De Souza (right) about what to expect after the baby’s born.

Jason LeCras for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras for NPR

Oyo, whose daughter is now nine-months-old, says the bootcamp helped him take an active lead in parenting. It was also a relief to his pregnant wife, he says, to see that he was studying up for fatherhood.

After the course,” Oyo says, “I shared everything I had learned, and once the baby was born, I became the trusted source for swaddling.”

Garfield tells prospective fathers that the art of proper swaddling, a method of wrapping babies that soothes them in the first couple of months, can be one of ‘dads secret parenting weapons.’ Additional tools include using a low voice to talk or sing to the baby, Garfield adds, or playing with the newborn during diaper changing time.

Learning these parenting techniques and the dynamics that develop when one new parent feels sidelined can be just as useful for adoptive parents and same-sex couples, Bay notes.

For all parents, raising children can feel a bit like being thrust into an ocean without knowing how to swim. But having an outlet where each caregiver can connect and learn from their peers helps make parenting less lonely. And it dismantles the myth of the ‘perfect parent.’

Greater parental harmony can help decrease spousal friction, which tends to rise when sleep deprivation and a lack of control are at an all-time high.

Reducing parental bickering pays off for the baby, too: Research suggests constant arguments can have an impact on a child’s brain development, disrupt healthy attachment, and raise a child’s risk of becoming anxious and depressed later in life.

Many mothers and fathers enter the wild ride of parenting hoping to be ‘expert parents.’ That’s a big mistake, Bay tells participants in his Bootcamp workshops.

“I always tell dads the goal isn’t to be ‘perfect,’ ” he says, “but ‘good enough.’ “

Juli Fraga is a psychologist and writer in San Francisco. You can find her on Twitter @dr_fraga.

Trump Administration Is In Court To Block Nation’s First Supervised Injection Site

Supporters of safe injection sites in Philadelphia rallied outside this week’s federal hearing. The judge’s ultimate ruling will determine if the proposed “Safehouse” facility to prevent deaths from opioid overdose would violate the federal Controlled Substances Act.

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

Philadelphia could become the first U.S. city to offer opioid users a place to inject drugs under medical supervision. But lawyers for the Trump administration are trying to block the effort, citing a 1980s-era law known as “the crack house statute.”

Justice Department lawyers argued in federal court Thursday against Safehouse, the nonprofit organization that wants to open the site.

U.S. Attorney William McSwain, in a rare move, argued the case himself. He says Safehouse’s intended activities would clearly violate a portion of the federal Controlled Substances Act that makes it illegal to manage any place for the purpose of unlawfully using a controlled substance. The statute was added to the broader legislation in the mid-1980s at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic in American cities.

Safehouse argues the law does not apply because the nonprofit’s main purpose is saving lives, not providing illegal drugs. Its board members say that the “crack house statute” was not designed to be applied in the face of a public health emergency.

“Do you think that Congress would want to send volunteer nurses and doctors to prison?” asked former Philadelphia Mayor and Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell, who is on Safehouse’s board, after the hearing. “Do you think that’s a legitimate result of this statute? Of course not. No one could have ever contemplated that, ever!”

Safehouse earned the backing of Philadelphia’s mayor, health department, and district attorney, who announced they would support a supervised injection site in January 2018 as another tool to combat the city’s dire overdose crisis.

More than 1,100 people died of overdoses in Philadelphia in 2018 — an average of three people a day. That’s triple the city’s homicide rate.

In response, public health advocates and medical professionals teamed up with the operators of the city’s only syringe exchange to found Safehouse. They created a plan for its operations, and began scouting a location.

But the Trump Administration sued the nonprofit in February to block the supervised injection site from opening.

In June, the Justice Department filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings– essentially asking the judge to rule on the case based on the arguments that had already been submitted. Since then, a range of parties have filed amicus briefs in support of or in opposition to the site. Attorneys general, mayors, and governors from across the country filed briefs backing Safehouse, while several neighborhood associations in Kensington and the police union filed against it.

U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh requested an evidentiary hearing to learn more about the nuts and bolts of how the facility would work, were it to open. At that hearing, in August, Safehouse’s legal team, led by Ilana H. Eisenstein, explained that Safehouse would not provide drugs, but that people could bring their own to inject while medical professionals stood by with naloxone, the overdose reversal drug. They said Safehouse would also be an opportunity for people to get access to treatment, if they were ready to commit to that.

Safehouse vice president Ronda Goldfein said the only difference between what Safehouse would do — and what’s already happening at federally sanctioned needle exchanges and the city’s emergency departments — is permit drug injection to happen in a safe, comfortable place.

“If the law allows for the provision of clean equipment, and the law allows for the provision of naloxone to save your life, does the law really not allow you to provide support in that thin sliver in between those federal[ly] permissible activities?” she said.

McSwain contends operating in that “sliver” is exactly what makes Safehouse illegal.

Much of the debate at Thursday’s hearing revolved around interpreting the word “purpose.” The statute in the Controlled Substances Act makes it illegal for anyone to “knowingly open … use or maintain any place … for the purpose of … using any controlled substance.”

The federal government says it’s simple: Safehouse’s purpose is for people to use drugs. McSwain conceded the facility will also provide access to treatment, but so does Prevention Point, the city’s only syringe exchange. Effectively, he argued, the only difference between Safehouse and what’s already going on elsewhere would be that people could inject drugs at Safehouse, which is prohibited by the statute.

“If this opens up, the whole point of it existing is for addicts to come and use drugs,” McSwain said.

Safehouse said its purpose is to keep people at risk of overdose from dying.

“I dispute the idea that we’re inviting people for drug use,” Eisenstein argued.

“We’re inviting people to stay to be proximal to medical support.”

McSwain conceded that if Safehouse were to offer the medical support without opening up a space specifically for people to use drugs, the statute would not apply.

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney spoke Thursday in support of the Safehouse injection site to reduce the number of deadly overdoses in Philadelphia. More than 1,100 people died of overdoses in the city in 2018 — an average of three people a day.

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

“If Safehouse pulled an emergency truck up to the park where people are shooting up, I don’t think [the statute] would reach that. If they had people come into the unit, that would be different,” he said. Mobile units and tents in parks are supervised injection models that other cities like Montreal and Vancouver have implemented.

Safehouse has also said it hasn’t ruled out the idea that it might incorporate a supervised injection site into another medical facility or community center, which would indisputably have other purposes, as well.

McSwain ultimately argued that Safehouse had come to the “steps of the wrong institution,” and that if it wanted to change the law, it should appeal to Congress. He accused Safehouse’s board of hubris, pointing to Safehouse president Jose Benitez‘s testimony at the August hearing, where he acknowledged that they hadn’t tried to open a site until now because they feared the federal government would think it was illegal and might shut it down.

“What’s changed?” asked McSwain. “Safehouse just got to the point where they thought they knew better.”

“Either that, or it’s the death toll,” Judge McHugh replied.

Supervised injection sites are used widely in Canada and Europe, and studies have shown that they can reduce overdose deaths and instances of injection-related diseases like HIV and hepatitis C. San Francisco, Seattle, New York City, Ithaca, N.Y., and Pittsburgh, Pa., among other U.S. cities, have expressed interest in opening a similar site, and are watching the Philadelphia case closely. In 2016, a nonprofit in Boston opened a room where people can go after injecting drugs, to ride out their high. The room has nurses equipped with naloxone standing by.

The Justice Department’s motion for the judge to rule on the pleadings is still pending. McHugh could decide he now has enough information to issue a ruling, or he might request more hearings, arguments or a full fledged trial.

Safehouse’s legal team said this week that if the judge rules in its favor, it might request a preliminary injunction in the form of relief — to allow the facility to open early.

“We recognize there’s a crisis here,” said Safehouse’s Goldfien. “The goal would be to open as soon as possible.”

This story is part of NPR‘s reporting partnership with WHYY and Kaiser Health News.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WHYY and Kaiser Health News.

For Health Workers Struggling With Addiction, Why Are Treatment Options Limited?

Dr. Peter Grinspoon was a practicing physician when he became addicted to opioids. When he got caught, Grinspoon wasn’t allowed access to what’s now the standard treatment for addiction — buprenorphine or methadone (in addition to counseling) — precisely because he was a doctor.

/Tony Luong for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

/Tony Luong for NPR

Peter Grinspoon got addicted to Vicodin in medical school, and still had an opioid addiction five years into practice as a primary care physician.

Then, in February 2005, he got caught.

“In my addicted mindframe, I was writing prescriptions for a nanny who had since returned back to another country,” he says. “It didn’t take the pharmacist long to figure out that I was not a 19-year-old nanny from New Zealand.”

One day, during lunch, the state police and the DEA showed up at his medical office in Boston.

“I start going all, ‘I’m glad you’re here. How can I help you?’ ” he says. “And they’re like, ‘Doc, cut the crap. We know you’re writing bad scripts.’ “

He was fingerprinted the next day and charged with three felony counts of fraudulently obtaining a controlled substance.

He also was immediately referred to a Physician Health Program, one of the state-run specialty treatment programs developed in the 1970s by physicians to help fellow physicians beat addiction. Known to doctors as PHPs, these programs now cover other sorts of health providers, too.

The programs work with state medical licensing boards — if you follow the treatment and monitoring plan they set up for you, they’ll recommend to the board that you get your medical license back, Grinspoon explains. It’s a significant incentive.

“The PHPs basically say, ‘Do whatever we say or we won’t give you a letter that will help you get back to work,’ ” Grinspoon says. “They put a gun to your head.”

But the problem, he and other critics say, is that, for various reasons, most PHPs don’t allow medical professionals access to the same evidence-based, “gold standard” treatment that addiction specialists today recommend for most patients addicted to opioids: medication-assisted treatment.

Grinspoon was told that to avoid a criminal record he would need to spend 90-days at an inpatient center in Virginia; there, he was not allowed access to the most common MAT prescription of counseling plus buprenorphine or methadone. These drugs are particular members of the opioid family that have been shown to suppress cravings for heroin, fentanyl and other frequently abused opioids. (Another drug, naltrexone, works by blocking opioids’ action, and is also sometimes prescribed as a component of medication-assisted treatment.)

“Why would you send this Jewish atheist to a religious, Christian rehab place in Virginia?” Grinspoon says. “It didn’t make any sense. I was just sitting there listening to people recite the Lord’s Prayer and hold hands. And I’m not against the Lord’s Prayer, but it just didn’t help me.”

At the same time, Grinspoon was forced off all the drugs he’d been taking “cold turkey,” without the medical support that would have eased withdrawal pangs and cravings. “It was completely insane,” he says.

“Why on earth,” Grinspoon adds, “would you deny physicians — who are under so much stress and who have a higher access and a higher addiction rate — why would you deny them the one lifesaving treatment for this deadly disease that’s killing more people in this country every year than died in the entire Vietnam War? There’s no reason for it.”

Grinspoon eventually recovered, but only, he says, after going through several “awful” rehab experiences. “I recovered despite going to rehab not because I went to rehab,” he says.

Today, he is a licensed primary care doctor and teaches at Harvard Medical School. He has also written a book about his experience with addiction called Free Refills.

Addiction specialists call for an end to the medication ‘ban’

While there is some variation in the particular rules and policies that each state’s physician health program follows, Dr. Sarah Wakeman of Harvard and the Massachusetts General Hospital Substance Use Disorder Initiative, says most PHPs don’t refer patients to addiction programs that include medication as part of their treatment. And that’s a problem, she says.

“I think the underlying issue is stigma and a misunderstanding of the role of medication,” Wakeman says, “and this idea that a non-medication-based approach is somehow better than someone taking the medication to control their illness.”

She co-authored a recent opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Practicing What We Preach — Ending Physician Health Program Bans on Opioid-Agonist Therapy,” along with collaborators Leo Beletsky and Dr. Kevin Fiscella.

“Systematically denying clinicians access to effective therapy is bad medicine, bad policy and discriminatory,” they write in NEJM. “We call on the health care sector to practice what it preaches, by discarding this antiquated norm.”

“It’s the peak of hypocrisy and absurdity,” Beletsky, a professor of law at Northeastern University tells NPR.

“I work with a lot of folks who are health professionals themselves, who are on the front lines advocating and fighting against stigma, trying to get policies and practices to align more closely with the science,” he says. “If those very same people were themselves struggling with addiction they would not have access to those medications.”

The strict policies of PHPs might have a chilling effect on health professionals who have opioid use disorder and need help, Beletsky and Wakeman believe.

A proven record, and reasons for caution

So what do the institutions getting blamed here — Physician Health Programs — have to say about all this?

Dr. Christopher Bundy is the executive medical director of Washington state’s PHP and the president-elect of the Federation of State Physician Health Programs.

He wants to make clear, first of all, that there is no systematic ban against the use of medication-assisted treatment, and no health care provider should avoid seeking help.

“There are doctors today across the country who are being monitored on buprenorphine,” he says. “And not just physicians. Nurses and other health professionals — certainly nurses in our state are able to work on buprenorphine.”

Bundy acknowledges, though, that those cases are not the norm.

There are “rational and understandable reasons,” he says, why such medications are often not used in rehab programs aimed at health professionals.

For example, he cites concerns that medications like buprenorphine can affect cognition. PHPs also get pressure from other stakeholders, such as regulators and licensing boards not to use medication. And, he points out, the in-patient, non-medication treatment model has been proven to work with many health professionals across several decades, and he worries that changing it could open PHPs up to unnecessary risk.

“Our tendency is to err on the side of caution,” Bundy says, “especially when implementing therapies that have the potential to impair somebody’s ability to practice safely. Despite the fact that there are many who would like us all to believe that the jury is in [on medications like buprenorphine], more remains unknown than known, especially when it comes to how to appropriately use these medications in safety-sensitive professionals.” That includes some other professions, such as pilots, he says — not just health workers.

Bundy notes that the public trusts PHPs to help health workers get healthy enough to be able to work with patients again — and that trust is fragile.

“We only need to have a case of one physician who is on buprenorphine where there’s a bad patient outcome,” he says, “to potentially have a whole other source of criticism being levied against the PHP for putting that physician back to work on a medication that may have played a role in that bad outcome.”

An overwhelming process

Bill Kinkle, a nurse in recovery from opioid use disorder, is right now going through the laborious process of getting his nursing license back. He lives outside of Philadelphia and is very public about his past drug use — he even has a podcast called “Health Professionals in Recovery.”

He’s working through an extensive treatment and monitoring program to get his nursing license back. Kinkle hopes to complete his third year of documented sobriety next fall; if so, he’ll then be eligible to practice nursing again.

When he was in the throes of his addiction and desperate to get into recovery, Kinkle says he was scared to do anything that might jeopardize his chance to get his career back.

Independence Blue Cross Foundation

YouTube

“In the nursing community, there is a ton of fear about the PHPs,” he says. “Everybody always told me, ‘You can’t be on Suboxone [a form of buprenorphine] — you can’t be on anything.'”

But he wanted to check for himself. So he called his state’s PHP to ask what their policy actually was.

” ‘The Board of Nursing will send you for some type of extensive cognitive testing,’ ” he says he was told. ” ‘Number one, the testing is very expensive. And it’s very difficult to find someone that will do the testing that we require.’ “

Daunted by that response, Kinkle says he instead “white knuckled it.” He went to abstinence-based programs — over and over again, and over and over. Many, many times, as soon as the rehab ended, Kinkle would relapse and turn to opioids again.

“A lot of those, I overdosed,” he says. “And had my wife not found me on the floor and been able to take care of me, I very well may have died.”

Kinkle believes “all that possibly could have been mitigated, had I gotten the gold standard of treatment, which is either buprenorphine or methadone.”

He doesn’t fault PHPs or licensing boards for their problematic policies, even though he thinks those policies put his life at risk. He says the stigma associated with addiction is ingrained in our culture; there’s no single institution to blame.

Both sides of the table

Peter Grinspoon was monitored in his recovery from opioid dependence by a PHP for seven years; and then later went to work for that very program.

“I’ve seen this issue from both sides,” he says. “I actually sat at the same table — in 2005 looking like something the cat dragged in, and then from 2013 to 2015 as a physician in recovery, helping other doctors.”

Grinspoon eventually wrote a book about his experiences and now works as a doctor at Mass General Hospital in Boston.

/Tony Luong for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

/Tony Luong for NPR

Grinspoon says in his experience, there was a de facto ban on medication-assisted treatment. In his state the ban was based, he says, on the assumption that the licensing board would reject any doctor-applicant who was taking a medication like buprenorphine. He says the feeling among staff at the PHP was “why bother to set someone up for failure?”

He believes such a policy needs to change, and that any cited concerns about cognitive impairment associated with medication-assisted treatment are unproven — and hypocritical.

“Why do they make medical students, interns and residents work 28-hour shifts then?” he points out. “I’d rather have someone on Suboxone [treat me] than someone who’s been up all night. And doctors are allowed to drink the night before [they go to work] — they’re allowed to take Ambien for sleep. That totally impairs you the next day.”

“This is pure stigma,” Grinspoon says. “It’s harming doctors. They need to reevaluate this completely.”

Treatment Limitations For Physicians With Opioid Addictions

Opioid addiction can happen to anyone, and that includes doctors and nurses. But unlike the general population, they are often barred from medications like methadone, the gold standard of treatment.

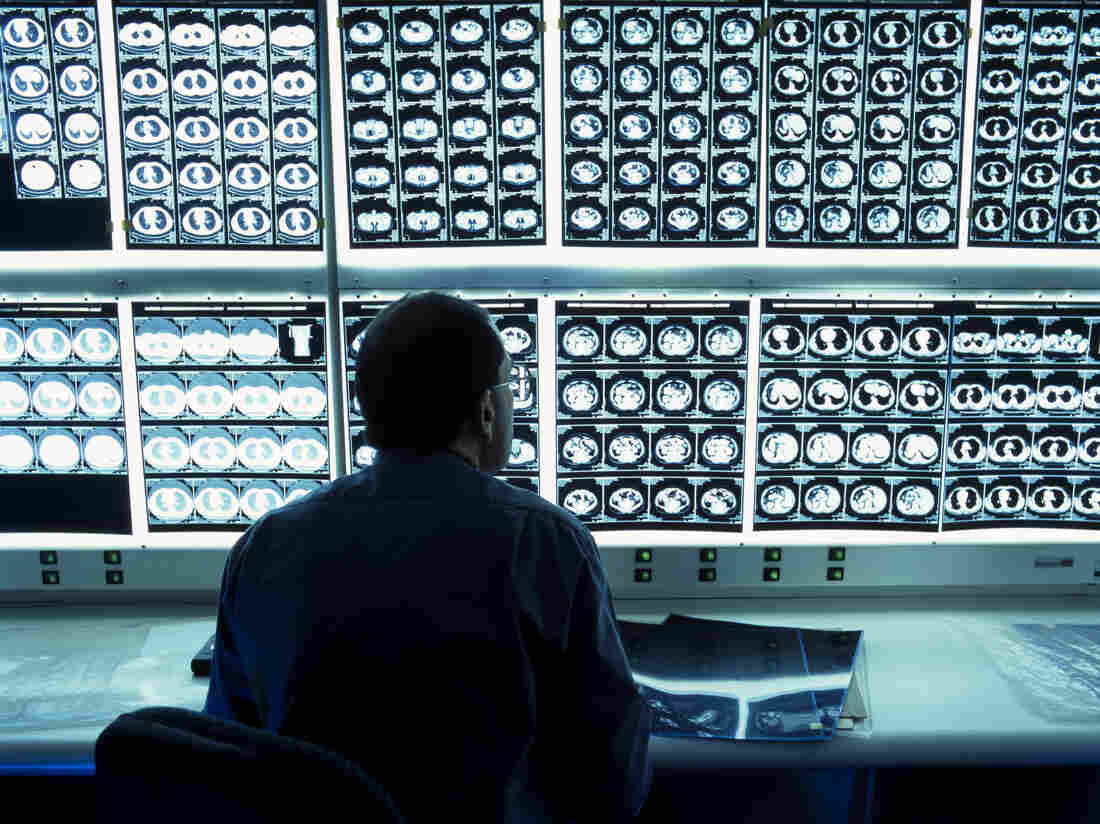

Groupon For Medical Scans? Discounted Care Can Have Hidden Costs

Groupon and other deal sites are the latest marketing tactic in medicine, offering bargain prices for services such as CT scans.

Colin Cuthbert/Science Photo Libra/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Colin Cuthbert/Science Photo Libra/Getty Images

Emory University medical fellow Dr. Nicole Herbst was shocked when she saw three patients who came in with abnormal results from chest CT scans they had bought on Groupon.

Yes, Groupon — the online coupon mecca that also sells discounted fitness classes and foosball tables.

Saw 3 pts in clinic for abnormal chest CTs BOUGHT ON GROUPON.

Evolution of my thoughts:

-What the $@&#? (*Google it*)

-hm actually priced pretty reasonably ?

-jeez if I ever need testing I’m going w/ Groupon, prob cheaper than insurance ????US healthcare is bonkers

— Nicole Herbst (@NicoleHerbst2) August 25, 2019

Similar deals have shown up for various lung, heart and full-body scans across Atlanta, as well as in Oklahoma and California. Groupon also offers discount coupons for expectant parents looking for ultrasounds, sold as “fetal memories.”

While Herbst declined to comment for this story, her sentiments were shared widely by the medical community on social media. The concept of patients using Groupons to get discounted medical care elicited the typical stages of Twitter grief: anger, bargaining and acceptance that this is the medical system today in the United States.

But, ultimately, the use of Groupon and other pricing tools is symptomatic of a health care market where patients desperately want a deal — or at least tools that better nail down their costs before they get care.

“Whether or not a person may philosophically agree that medicine is a business, it is a market,” says Steven Howard, who runs Saint Louis University’s health administration program.

By offering an upfront cost on a coupon site such as Groupon, medical companies are meeting people where they are, Howard argues. It helps drive prices down, he says — all the while marketing the medical businesses.

For Paul Ketchel, CEO and founder of MDsave, a site that contracts with providers to offer discount-priced vouchers on bundled medical treatments and services, the use of medical Groupons and his company’s success speak to the brokenness of the U.S. health care system.

MDsave offers deals at more than 250 hospitals around the country, selling vouchers for anything from MRIs to back surgery. It has experienced rapid growth and expansion in the several years since its launch.

Ketchel credits that growth to the general lack of price transparency in the U.S. health care industry amid rising costs to consumers. “All we are really doing is applying the e-commerce concepts and engineering concepts that have been applied to other industries to health care,” he argues.

“We are like transacting with Expedia or Kayak,” Ketchel says, “while the rest of the health care industry is working with an old-school travel agent.”

A closer look at those deals

Crown Valley Imaging, in Mission Viejo, Calif., has been selling Groupon deals for services including heart scans and full-body CT scans since February 2017 — despite what Crown Valley’s president, Sami Beydoun, called Groupon’s aggressive financial practices. According to him, Groupon dictates the price for its deals based on the competition in the area — and then takes a substantial cut.

“They take about half. It’s kind of brutal. It’s a tough place to market,” Beydoun says. “But, the way I look at it is you’re getting decent marketing.”

Groupon-type deals for health care aren’t new. They were more popular in 2011, 2012 and 2013, when Groupon and its then-competitor LivingSocial were at their height, but the industry has since lost some steam. Groupon stock and valuation have tumbled in recent years, even after buying LivingSocial in 2016.

Groupon did not respond to requests for comment on how many medical offerings it features or its pricing structure.

“Groupon is pleased any time we can save customers time and money on elective services that are important to their daily lives,” spokesman Nicholas Halliwell writes in an emailed statement. “Our marketplace of local services brings affordable dental, chiropractic and eye care, among other procedures and treatments, to our more than 46 million customers daily and helps thousands of medical professional[s] advertise and grow their practices.”

In Atlanta, two imaging centers that each offered discount coupons from Groupon say the deals have driven in new business. Bobbi Henderson, the office manager for Virtual Imaging’s Perimeter Center, says the group has been running the deal for a heart CT scan, complete with consultation, since 2012; it’s currently listed at $26 — a 96% discount. More than 5,000 of the company’s coupons have been sold, according to the Groupon site.

Brittany Swanson, who works in the front office at OutPatient Imaging in the Buckhead neighborhood of Atlanta, says she has seen hundreds of customers come through since the center posted Groupon coupons for mammograms, body scans and other screenings around six months ago. Why did the medical practice turn to Groupon discounts?

“Honestly, we saw the other competition had it,” Swanson says.

A lot of the deals offered are for preventive scans, she says, providing patients incentives to come in.

But Dr. Andrew Bierhals, a radiology safety expert at Washington University in St. Louis’ Edward Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, warns that such deals may be leading patients to get unnecessary initial scans — which can lead to unnecessary tests and radiation.

“If you’re going to have any type of medical testing done, I would make sure you discuss with your primary care provider or practitioner,” he cautions.

Appealing to patients who fall through an insurance gap

Because mammograms are typically covered by insurance, Swanson says, she believes OutPatient Imaging’s $99 Groupon deal is filling a gap for women who lack insurance. The cost of such breast screenings for those who don’t have insurance varies widely but can be up to several hundred dollars without a discount.

Howard says Groupon has long been used to fill insurance gaps for dental care. He often bought such deals over the years to get cheaper dental cleanings when he didn’t have insurance that covered that.

But advanced medical scans involve a higher level of scrutiny, as Chicagoan Anna Beck recently learned. In 2015, she and her husband, Miguel Centeno, were told he needed to get a chest CT after a less advanced X-ray at an urgent care center showed something suspicious.

Since her husband had just been laid off and did not have insurance, they shopped online to look for the cheapest price. They ended up driving out to the suburbs to get a CT scan at an imaging center there.

“I knew that CT scans had such a wide range of costs in a hospital setting,” Beck says. “So going in knowing that I could price check and have some idea of how much I’d be paying and a little more control” was preferable than going to the hospital.

On the drive back into the city though, the imaging center called and told them to go straight to the hospital — the CT had revealed a large mass that turned out to be a germ-cell tumor.

Fortunately, Centeno’s cancer is now in remission, his wife says. But their online shopping cost them more money than if they’d gone straight to the hospital initially. The hospital gave them charity care. And although Beck took along a CD of the scans Centeno had bought online, the hospital ended up taking its own scans as well.

“You’re trying to cut costs by getting a CT out of the hospital,” Beck says. “But they’re just going to redo it anyway.”

Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent, nonprofit program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

California Again Considers Making Abortion Pills Available At Public Colleges

Abortion opponents in Sacramento, Calif., protest legislation that would require public university campuses in California to provide the pills used in medication abortion.

April Dembosky/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

April Dembosky/KQED

When Jessy Rosales was a sophomore at the University of California, Riverside, she had a boyfriend and she was taking birth control pills. Then out of nowhere, she started feeling sick.

“I just thought it was the stomach flu,” she says. “It turns out I was pregnant.”

Rosales was clear that she was not ready to have a baby. She wanted a medication abortion, where she would take one pill at the clinic and a second one at home a day or two later to induce a miscarriage.

“I just wanted the intimacy of dealing with it on my own, in the privacy of my own home,” she says. “And being able to cry if I wanted to cry or just being able to curl up in my bed right away.”

Public university health centers in California do not perform abortions. But state lawmakers are expected to pass a bill in the coming weeks that would require student health centers at all 34 state campuses to provide medication abortions. If the measure becomes law, it will be the first of its kind in the U.S.

The bill’s supporters say they want to remove the obstacles women face accessing medical abortion off campus. For example, Rosales was given three off-campus referrals for abortion providers by her student health center. But the first clinic she called didn’t perform abortions after all. The second didn’t take her insurance.

By the time she could get an appointment at a third clinic, she was already into the second trimester of pregnancy — too late for a medication abortion, which can only be done up to 10 weeks. Rosales ended up having a surgical procedure.

“The doctor kept telling me to relax … and I couldn’t because it just hurt so bad,” she recalls. “I was just afraid and alone.”

Rosales graduated last year and is now advocating for the bill (SB 24) as a reproductive justice activist with the Women’s Foundation of California. She wants other students to have easier access to the abortion pill than she did.

It took too long for Jessy Rosales to find a clinic near the University of California, Riverside, that would provide a medication abortion and accept her insurance. She’s now advocating for a state bill to make the pills available at public university health centers in California.

Courtesy of Planned Parenthood

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Planned Parenthood

Opponents of the bill have organized several rallies against it. In August, about 60 protesters in yellow T-shirts gathered outside a church in Sacramento, Calif., their heads bowed as a priest led them in prayer. Then they marched around the state’s Capitol, chanting, “Don’t kill babies! Don’t kill babies!”

While a consortium of women’s groups that support abortion rights has promised to pay for all the required ultrasound equipment and upfront training costs of providing the abortion pill on campus, eventually universities would likely need to dip into tax dollars or student fees for ongoing costs.

Abortion opponents such as Michele LaMonica object to that.

“Not on my dime, not on my dime,” LaMonica says. “Tax me to help the homeless. Tax me to help social services, but don’t tax me to pay for the disposal of human life.”

Insurers are already required to cover abortion under California law, and state tax dollars do go toward abortions provided through Medi-Cal, the state version of Medicaid for low-income patients. However, none of the UC campuses and only some of the CSU campuses get reimbursed for health services through Medi-Cal. University officials testified during legislative hearings on the bill last year that it could be an administrative or fiscal burden to establish billing systems to provide the abortion pill on campus. They predicted that some clinical costs, as well as security and liability costs, could fall directly to the universities and get passed on to students.

Up to 519 women at public universities seek a medication abortion every month in California, according to a study published last summer in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

The same research found that off-campus abortion providers were an average of 6 miles away from public university campuses in California.

Former Gov. Jerry Brown cited this stat when he vetoed a version of the same bill (SB 320) last year, saying the legislation was not necessary.

“Six miles away — that’s like a $5 Uber ride,” said abortion opponent Nick Reynosa, the Northern California regional coordinator for Students for Life of America.

He says the campaign is more about politics than need.

“Over the last decade, many pro-choice activists feel that in red states, there’s been a lot of momentum toward more abortion restrictions. This is a way to say, ‘No. Here, in blue California, we’re going to affirm or expand [the right to an abortion],’ ” Reynosa says.

The bill’s supporters don’t deny it. Phoebe Abramowitz was part of the student team that launched the campus campaign for medication abortions at UC Berkeley four years ago.

“Now that we’re doing statewide advocacy, we’re hoping to set a national precedent that we can, even in these really hostile times to women and queer people, move access to abortion forward,” she says. “It’s more important now than it even was a year ago.”

When Brown vetoed the bill last year, then-gubernatorial candidate Gavin Newsom said he would have supported it. He won the election about a month later, and advocates are optimistic that he will side with them this time around.

The state Legislature has until mid-September to pass the bill, and the governor has a month after that to sign or veto it.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with KQED and Kaiser Health News.

U.S. Authorities Reconsider Some Requests To Stay From Immigrants Seeking Medical Aid

Immigration authorities are reconsidering some requests from migrants to be allowed to stay in the U.S. to get medical treatment. But others hoping to get care here could be facing deportation.

When Employer Demands Clash With Health Care Obligations

NPR’s Steve Inskeep talks to Paul Spiegel, one of several doctors at Johns Hopkins University arguing that physicians who work in immigration detention centers could be violating the Hippocratic Oath.

What Would Trumpcare Look Like? Follow GOP’s ‘Choice And Competition’ Clues

President Donald Trump talked about expanding health coverage options for small businesses in in a Rose Garden gathering at the White House in June.

Al Drago/Bloomberg/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Al Drago/Bloomberg/Getty Images

While many Capitol Hill Republicans would like to avoid another public debate about whether to repeal the Affordable Care Act, President Donald Trump and his appointees keep bringing it up — promising their own health plan that would be “phenomenal” and make the GOP “the party of health care.”

“We’re actively engaged in conversations” on what to do, Medicare chief Seema Verma said last month. And Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway has indicated a health care announcement might come in September.

Behind the pronouncements lies a dilemma: whether or not to stray beyond efforts underway to improve the nation’s health care system — loosening insurance regulations, talking about drug prices and expanding tax-free health savings accounts — to develop an overarching plan.

For the White House, it’s a fraught decision.

A comprehensive plan could serve as a lightning rod for opponents. Conversely, not having a plan for replacing some of the most popular parts of Obamacare — such as its coverage protections for people with preexisting medical conditions — could leave the GOP flat-footed if an administration-supported lawsuit now before the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals were to invalidate the sweeping health law.

“This is a real conundrum,” says Dean Rosen, a Washington, D.C., health policy consultant who often advises Republicans. “There is a risk with action or inaction.”

No matter how the 5th Circuit rules, its decision, which could come soon, is likely to be stayed while the issue heads to the Supreme Court. Such a delay would give the Trump administration time to flesh out a proposal if the appeals judges throw out the ACA. But it would also ensure that a health care debate is front and center during the presidential campaign.

Right now, polls show the public is focused on health costs, says professor Robert Blendon, who directs the Harvard Opinion Research Program, which studies public knowledge of health care and policy issues. Consumers are concerned about what they pay at the pharmacy counter, or about the sum of their insurance premiums and deductibles.

“Most voters are not interested in another debate on a new health plan,” Blendon says.

But if the 5th Circuit upholds a Texas ruling overturning the entire ACA, “that changes the entire framework,” he adds. “The administration could not just say, ‘Oh, we’ll have something great.’ They would have to have something outlined.”

Supporters and critics say likely elements are already in plain sight, both in executive actions and proposals in the president’s budget as well as in a little-noticed interagency white paper released late last year, called Reforming American’s Health Care System Through Choice And Competition.

The president has won praise from both conservatives and liberals for initiatives such as his proposal to require hospitals to post their actual, negotiated prices, and some strategies to lower drug prices. But legal battles from industry could thwart such initiatives.

On these topics, “a lot of what they’ve proposed has been pretty smart,” says Shawn Gremminger, senior director of federal relations at the liberal Families USA advocacy group.

Still, Gremminger points to other administration actions — such as loosening rules on health insurers to allow sales of what critics call “junk” insurance, because they don’t have all the consumer protections of ACA policies, or promoting work requirements for Medicaid recipients — as strong hints to what might be in any eventual election-related plan.

“I think what we’ll see is a lot of that same sort of stuff, warmed-over and put into a new package,” Gremminger says. “We fully expect it will include a lot of really terrible ideas.”

For other policy clues, some Trump advisers, like Brian Blase, a former special assistant to the president at the National Economic Council, who is now with the Texas Public Policy Foundation, say look no further than that 2018 interagency report.

The 114-page document, a joint publication of the U.S. Departments of Labor, Treasury and Health and Human Services, includes more than two dozen recommendations that broadly focus on loosening federal and state regulations, limiting hospital and insurer market power and prompting patients to be more price-conscious shoppers.

Many are long-standing, free-market favorites of Republicans, such as increasing the use of health savings accounts — which allow consumers to set aside money, tax-free, to cover medical expenses. Other ideas are not typically associated with the GOP, such as increased federal scrutiny of mergers of hospitals and insurers; such mergers have driven up prices.

The white paper also calls for easing restrictions on Medicare Advantage plans, which offer an alternative to the traditional fee-for-service Medicare. The Trump proposal would allow the advantage program to have smaller networks of doctors and hospitals — presumably ones that agreed to charge less.

“The administration knows where it is going on health care,” Blase says.

If the court strikes down the ACA, he expects the administration to release a plan supporting “generously funded, state-based high-risk pools.”

Such pools existed in most states before the ACA. They helped provide coverage for people with preexisting conditions who were denied policies by insurers. But the pools were expensive, so they often were underfunded — capping members’ benefits and producing long waiting lists.

Not everyone thinks the white paper is a plan, but more of a “combination of policy ideas and political statements,” says Joe Antos at the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute.

Still, he doubts the GOP needs a comprehensive health proposal. Republicans are more likely to gain politically by merely attacking the Democrats’ ideas, Antos says, especially if the Democratic nominee backs proposals for a fully government-funded health care system, such as the Medicare for All plans some candidates support.

Republicans will “have their own one-liners, saying they are dedicated to protecting people with preexisting conditions. That might be enough for a lot of people,” Antos says.

Politically, taking on the Affordable Care Act — or not taking it on — are both risky. While many voters don’t understand all that the federal health law does, some of its rules enjoy broad support. That’s particularly true of the protections for people with medical problems — under the current law, insurers are barred from rejecting them for coverage or charging them more than people without such conditions.

The Republican effort to repeal the ACA galvanized activists during the 2018 midterm elections and is credited with boosting Democrats to victory in many House districts.

Analysts on both sides expect concerns about health costs and health law to play a large role again in 2020.

For Republicans, “the risk of doing nothing potentially leaves no port in a storm if the ACA is overturned legally,” Rosen says. “But a more limited version, which is what most Republicans are for, is likely to be met with the same concerns. No matter what the president says, it won’t be enough for the Democrats.”

Opinion poll analyst Blendon says there is an additional unknown: Which Democrat will win the nomination — and what type of coverage will she or he back?

Even as the GOP is split on how to address health care concerns, so too are the Democrats.

“If they are reading the same polling data as I am, they would have serious proposals for lowering drug and hospital costs, but not offer a national health plan,” Blendon says.

The Democrats’ most progressive wing, led by Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, wants Medicare for All, which would essentially eliminate private and job-based coverage. Recent polls have shown voters are not keen to lose private insurance.

The party’s center, led by former Vice President Joe Biden, wants to keep the ACA but apply “fixes” to make insurance purchased by individuals more affordable.

“If the Democratic nominee is running on keeping the ACA, the Republican will have to have an alternative,” Blendon says. But, if the nominee supports Medicare for All, Blendon predicts simply a GOP “anti-campaign” targeting the Democrat’s idea as unworkable, socialist or a danger to Medicare.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Report: Hundreds Of Florida Nursing Homes Fall Short Of Post-Irma Regulations

NPR’s Michel Martin talks with reporter Elizabeth Koh about how Florida nursing facilities are preparing — or not — for intense hurricanes.