Poll: Nearly 1 in 5 Americans Says Pain Often Interferes With Daily Life

According to the latest NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll exercise, including stretching and yoga, is popular among younger people as a way to relieve pain.

Daniel Grill/Getty Images/Tetra images RF

hide caption

toggle caption

Daniel Grill/Getty Images/Tetra images RF

At some point nearly everyone has to deal with pain.

How do Americans experience and cope with pain that makes everyday life harder? We asked in the latest NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll.

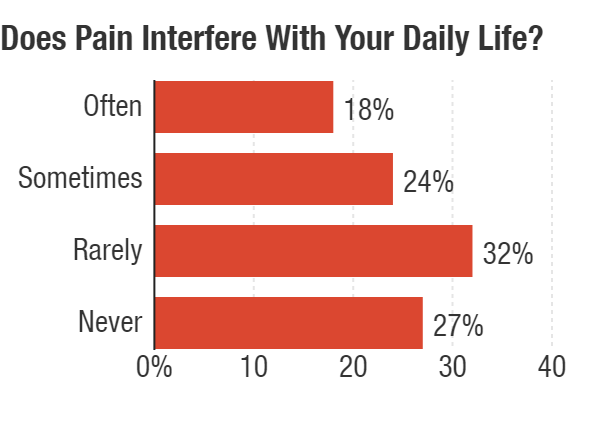

First, we wanted to know how often pain interferes with people’s ability to work, go to school or engage in other activities. Overall, 18% of Americans say that’s often a problem for them. Almost a quarter – 24% — say it’s sometimes the case.

(Note: Because of rounding, total exceeds 100%)

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

The degree to which pain is a problem varies by age, with 22% of people 65 and older saying pain interferes often with their daily lives compared with only about 9% of people 35 and younger.

Once pain strikes, how do people deal with it?

The poll found that 63% of people had sought care for their pain and 37% hadn’t. Younger people were less likely to have pursued care.

The most common approach is an over-the-counter pain reliever. Sixty percent of people said that is something they do. Another popular choice, particularly among younger people, is exercise, including stretching and yoga. Forty percent of those under 35 say exercise is a way they seek relief. Only 11% of people 65 and older say exercise is something they try for pain. Overall, 26% of people see exercise as helpful for their pain.

That level of exercise is “really exciting to see,” says Brett Snodgrass, a nurse practitioner and clinical coordinator of palliative medicine at Baptist Hospitals in Memphis, Tenn. In her experience, not nearly as many people were doing that, even a few years ago.

She says a decline in opioid prescribing could be part of the reason for the change. “Often prescribers were settling for prescriptions,” she says of health care providers’ longstanding approach. “Now that there’s less prescribing, patients are having to take more responsibility” for managing their pain, she says.

But options such as exercise and physical therapy are easier to access for people with higher incomes. Snodgrass points to the poll’s finding that only 15% of people whose income was less than $25,000 a year cite exercise as a way they relieve pain. By comparison, about a third of people making $50,000 or more annually say it’s one way they deal with it.

(Note: Up to two choices were allowed.)

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

About 15% of Americans do turn to a prescription medicine to help get relief. People 35 and under were least likely to get a prescription drug for pain – only 3%. Older people, those 65 and older, were most likely to make use of a prescription medicine, with 23% opting for that approach.

In terms of treatment, pain needs to be viewed holistically, so that reliance on medicines alone doesn’t drive decisions. “If we don’t pay attention to pain as a public health issue, I think we’re going to be addressing half of the problem and causing another problem,” says Dr. Anil Jain, vice president and chief health information officer at IBM Watson Health.

In light of the efforts to reduce opioid use, we asked if people who are taking opioids for pain are concerned about becoming addicted: 16% said yes; 84% said no.

A little more than a third of people taking opioids said they were worried about losing access to opioids compared with about two-thirds who aren’t.

The nationwide poll surveyed 3,004 people during the first half of March. The margin of error is +/- 1.8 percentage points.

You can find the full results here.

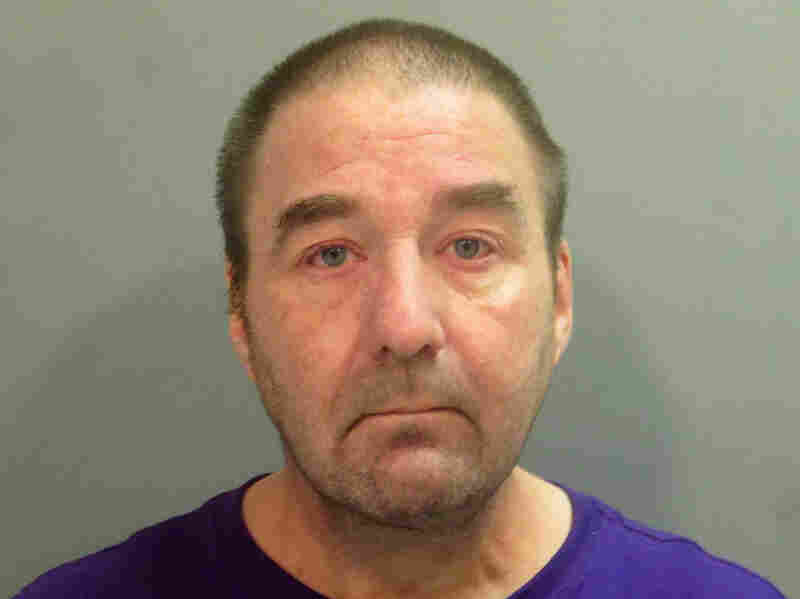

Former Arkansas VA Doctor Charged With Involuntary Manslaughter In 3 Deaths

Dr. Robert Levy, a pathologist fired from an Arkansas veterans hospital after officials said he had been impaired while on duty.

AP

hide caption

toggle caption

AP

A former pathologist at an Arkansas veteran’s hospital was charged with three counts of involuntary manslaughter in the deaths of three patients whose records he allegedly falsified to conceal his misdiagnoses.

According to federal prosecutors, Dr. Robert Morris Levy, 53, is also charged with four counts of making false statements, 12 counts of wire fraud and 12 counts of mail fraud, stemming from his efforts to conceal his substance abuse while working at the Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks.

Levy was suspended from work twice — in March 2016 and again in October 2017 — for working while impaired, before he was fired in April 2018.

A June 2018 review of his work examined 33,902 cases and found more than 3,000 mistakes or misdiagnoses of patients at the veteran’s hospital dating back to 2005. Thirty misdiagnoses were found to have resulted in serious health risks to patients.

The three deaths came as a result of an incorrect or misleading diagnosis. In one case, according to prosecutors, a patient died of prostate cancer after Levy concluded that a biopsy indicated that he didn’t have cancer.

“This indictment should remind us all that this country has a responsibility to care for those who have served us honorably,” Duane Kees, the United States Attorney for the Western District of Arkansas said in a statement. “When that trust is violated through criminal conduct, those responsible must be held accountable. Our veterans deserve nothing less.”

Kees said Levy went to great lengths to conceal his substance abuse even during a period when he had pledged to maintain his sobriety.

Levy used 2-methyl-2-butanol, a chemical substance that intoxicates a person, “but is not detectable in routine drug and alcohol testing methodology,” the statement said.

The Downside Of Planned Parenthood Leaving The Federal Title X Program

NPR’s Noel King speaks with Dr. Sarah Traxler, chief medical officer of Planned Parenthood’s North Central States, about the impact of losing Title X funding.

News Brief: Afghan Bombing, Deadly Force, Title X Changes

A suicide bomber killed 63 people at an Afghan wedding. California’s governor is expected to sign a bill regarding when police can use deadly force. Title X changes take effect Monday.

Planned Parenthood May Reject Federal Funds Over Changes To Title X

It appears some health care providers that offer birth control, such as Planned Parenthood, are going to withdraw from the federal Title X program. Changes to Title X take effect Monday.

No Mercy: After The Hospital Closes, How Do People Get Emergency Care?

Mercy Hospital Fort Scott closed in December, leaving Fort Scott Kan., without its longtime provider of emergency medical services.

Sarah Jane Tribble for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Sarah Jane Tribble for Kaiser Health News

For more than 30 minutes on a frigid February morning, Robert Findley lay unconscious in the back of an ambulance as paramedics hand-pumped oxygen into his lungs.

They were waiting for a helicopter to land at a helipad just across the icy parking lot next to Mercy Hospital Fort Scott, which closed in December. The night before, Findley had fallen on the slick driveway outside his home while checking the mail. He had laughed it off, ate dinner and went to bed.

In the morning, he wouldn’t wake up. Linda, his wife, called 911.

When the Fort Scott, Kan., paramedics arrived, they suspected he had an intracerebral hemorrhage. Robert Findley needed specialized neurological care and the closest available center was located 90 miles north in Kansas City, Mo.

After rural hospitals like the one in Fort Scott close, one of the thorniest dilemmas communities face is how to provide emergency care, particularly for patients who require specialized expertise. In times of crisis, the local emergency workers can find themselves dealing with changing leadership, budgets and questions about where to take patients. Air ambulance companies are often seen as a key part of the solution.

The dispatcher for Air Methods, a private air ambulance company, checked with at least four bases before finding a pilot to accept the flight for Robert Findley, according to a 911 tape obtained by Kaiser Health News through a Kansas Open Records Act request.

Linda Findley’s husband, Robert, opened Findley Body Repair in 1975. Linda says she doesn’t know what she’s going to do with the Fort Scott, Kan., business. She kept two workers on for six weeks after Robert’s death to close out active orders. “I guess I’ll have to have an auction someday,” Findley says.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

“My Nevada crew is not available and my Parsons crew has declined,” the operator tells Fort Scott’s emergency line about a minute after taking the call. Then she says she will be “reaching out to” another crew.

Nearly seven minutes passed before one was en route.

When Linda Findley sat at her kitchen counter in late May and listened to the 911 tape, she blinked hard: “I didn’t know that they could just refuse. … I don’t know what to say about that.”

Both Mercy and Air Methods declined to comment on the case.

When Mercy Hospital Fort Scott closed at the end of 2018, hospital president Reta Baker had been “absolutely terrified” about the possibility of not having emergency care for a community where she had raised her children and grandchildren and served as chair of the local Chamber of Commerce.

Now, just a week after the ER’s closure, her fears were being tested.

Nationwide, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, and in each instance a community struggles to survive in its own way. In Fort Scott, home to 7,800, the loss of its 132-year-old hospital opened by nuns in the 19th century has wrought profound social, emotional and medical consequences. Kaiser Health News and NPR are following Fort Scott for a year to explore deeper national questions about whether small communities need a traditional hospital at all. If not, what would take its place?

A delay in emergency care can make the difference between life and death. Seconds can be crucial when it comes to surviving a heart attack, a stroke, an anaphylactic allergic reaction or a complicated birth.

Though air ambulances can transport patients quickly, the dispatch system is not coordinated in many states and regions across the country. And many air ambulance companies do not participate in insurance networks, which leads to bills of tens of thousands of dollars.

Knowing that emergency care was crucial, the hospital’s owner, St. Louis-based Mercy, agreed to keep Fort Scott’s emergency doors open an extra month past the hospital’s Dec. 31 closure, to give Baker time to find a temporary operator. A last-minute deal was struck with a hospital about 30 miles away to take it over, but the ER still needed to be remodeled and the new operator had to meet regulatory requirements. So, the ER closed for 18 days — a period that proved perilous.

A risky experiment

During that time, Fort Scott’s publicly funded ambulances responded to more than 80 calls for service and drove more than 1,300 miles for patients to get care in other communities.

Across America, rural patients spend more time in an ambulance than urban patients after a hospital closes, said Alison Davis, a professor at the University of Kentucky’ department of agriculture economics. Davis and research associate SuZanne Troske analyzed thousands of ambulance calls and found the average transport time for a rural patient was 14.2 minutes before a hospital closed; afterward, it increased nearly 77% to 25.1 minutes. For patients over 64, the increase was steeper, nearly doubling.

In Fort Scott this February, the hospital’s closure meant people didn’t “know what to expect if we come pick them up,” or where they might end up, said Fort Scott paramedic Chris Rosenblad.

During 18-day gap in ER services, Barbara Woodward slipped on ice outside a downtown Fort Scott business. She was driven 30 miles out of town of care. “I thought to myself that the back of the ambulance isn’t as comfortable as I thought it would be,” Woodward says.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

Barbara Woodward, 70, slipped on ice outside a downtown Fort Scott business during the early February storm. The former X-ray technician said she knew something was broken. That meant a “bumpy” and painful 30-mile drive to a nearby town, where she had emergency surgery for a shattered femur, a bone in her thigh.

About 60% of calls to the Fort Scott’s ambulances in early February were transported out of town, according to the log, which KHN requested through the Kansas Open Records Act. The calls include a 41-year-old with chest pain who was taken more than 30 miles to Pittsburg, an unconscious 11-year-old driven 20 miles to Nevada, Mo., and a 19-year-old with a seizure and bleeding eyes escorted nearly 30 miles to Girard, Kan.

Traveling those distances can harm patients’ health when they are experiencing a traumatic event, Davis said. They also prompt other, less obvious, problems for a community. The travel time keeps the crews absent and unable to serve local needs. Plus, those miles cause expensive emergency vehicles to wear out faster.

Mercy donated its ambulances to the joint city and county emergency operations department. Bourbon County Commissioner Lynne Oharah said he’s not sure how they will pay for upkeep and the buying of future vehicles. Mercy had previously owned and maintained the fleet, but now it falls to the taxpayers to support the crew and ambulances. “This was dropped on us,” said LeRoy “Nick” Ruhl, also a county commissioner.

Barbara Woodward’s bumpy ride was just the beginning of a difficult journey. She had shattered her femur and had trouble healing after an emergency surgery. In May, Woodward had a full hip replacement in Kansas City, Kan.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

Even local law enforcement feel extra pressure when an ER closes down, said Bourbon County Sheriff Bill Martin. Suspects who overdose or suffer split lips and black eyes after a fight need medical attention before getting locked up — that often forces officers to escort them to another community for emergency treatment.

And Bourbon County, with its 14,600 residents, faces the same dwindling tax base as most of rural America. According to the U.S. Census, about 3.4% fewer people live in the county compared with nearly a decade ago. Before the hospital closed, Bourbon County paid Mercy $316,000 annually for emergency medical services. In April, commissioners approved an annual $1 million budget item to oversee ambulances and staffing, which the city of Fort Scott agreed to operate.

In order to make up the nearly $700,000 difference in the budget, Oharah said the county is counting on the ambulances to transport patients to hospitals. The transports are essential because ambulance services get better reimbursement from Medicare and private insurers when they take patients to a hospital as compared to when they treat patients at home or at an accident scene.

Added response times

For time-sensitive emergencies, Fort Scott’s 911 dispatch calls go to Air Methods, one of the largest for-profit air ambulance providers in the U.S. It has a base 20 miles away in Nevada, Mo., and another base in Parsons, Kan., about 60 miles away.

The company’s central communications hub, known as AirCom, in Omaha, Neb., gathers initial details of an incident before contacting the pilot at the nearest base to confirm response, said Megan Smith, a spokeswoman for the company. The entire process happens in less than five minutes, Smith said in an emailed statement.

When asked how quickly the helicopter arrived for Robert Findley, Bourbon County EMS Director Robert Leisure said he was “unsure of the time the crew waited at the pad.” But, he added, “the wait time was very minimal.”

Rural communities nationwide are increasingly dependent on air ambulances as local hospitals close, said Rick Sherlock, president of the Association of Air Medical Services, an industry group that represents the air ambulance industry. AAMS estimates that nearly 85 million Americans rely on the mostly hospital-based and private industry to reach a high-level trauma center within 60 minutes, or what the industry calls the “golden hour.”

In June, when Sherlock testified to Congress about high-priced air ambulance billing, he pointed to Fort Scott as a devastated rural community where air service “helped fill the gap in rural health care.”

But, as Robert Findley’s case shows, the gap is often difficult to fill. After Air Methods’ two bases failed to accept the flight, the AirCom operator called at least two more before finding a ride for the patient. Air ambulances can be delayed because of bad weather or crew fatigue from previous runs.

The 1978 Airline Deregulation Act states that airline companies cannot be regulated on “rates, routes, or services,” a provision originally meant to ensure that commercial flights could move efficiently between states. Today, in practice, that means air ambulances have no mandated response times, there are no requirements that the closest aircraft will come, and they aren’t legally obligated to say why a flight was declined.

The air ambulance industry has faced years of scrutiny over accidents, including investigations by the National Transportation Safety Board and stricter rules from the Federal Aviation Administration. And Air Methods’ Smith said the company does not publicly report on why flights are turned down

because “we don’t want pilots to feel pressured to fly in unsafe conditions.”

Yet, a lack of accountability can lead the mostly for-profit providers to sometimes putting profits first, Scott Winston, Virginia’s assistant director of emergency medical services, wrote in an email. Sometimes companies accept a call knowing their closest aircraft is unavailable, rather than lose the business. “This could result in added response time,” he wrote.

Air ambulances don’t face the detailed reporting requirements imposed on ground ambulances. The National Emergency Medical Services Information System collects only about 50% of air ambulance events because the industry’s private operators voluntarily provide the information.

Ascension Via Christi’s Pittsburg, Kan., hospital took over responsibility for ER services in Fort Scott, Kan., after that town’s only hospital closed.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

Saving lives

It took months, but Baker persuaded Ascension Via Christi’s Pittsburg hospital, to reopen the ER. “They kind of were at a point of desperation,” said Randy Cason, president of Pittsburg’s hospital. The two Catholic health systems signed a two-year agreement, leaving Fort Scott relieved but nervous about the long term.

Ascension has said it is looking at potential facilities in the area, but it’s unclear what that means. Fort Scott Economic Development Director Rachel Pruitt said in a July 23 email, “No decisions have been made.” Fort Scott City Manager Dave Martin said the city has entered into a “nondisclosure agreement” with Ascension. Nancy Dickey, executive director of the Texas A&M Rural & Community Health Institute, said every community prioritizes emergency services. That’s because the “first hour appears to be vitally important in terms of outcomes,” she said.

And the Fort Scott ER, which reopened under Ascension on Feb. 18, has proved its value. In the past six months, the Fort Scott emergency department has taken care of more than 2,500 patients, including delivering three babies. In May, a city ambulance crew resuscitated a heart attack patient at his home and Ascension’s emergency department staff treated the patient until an air ambulance arrived.

In July, Fort Scott’s Deputy Fire Chief Dave Bruner read a note from that patient’s grateful wife at a city commission meeting: “They gave my husband the chance to fight long enough to get to Freeman ICU. As a nurse, I know the odds of Kevin surviving the ‘widow-maker’ were very poor. You all made the difference.”

Robert Findley died after falling on the ice during a winter storm this February in Fort Scott, Kan. Mercy Hospital had recently closed, so he had to be flown to a neurology center 90 miles north in Kansas City, Mo.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

By contrast, Linda Findley believes the local paramedics did everything possible to save her husband but wonders how the lack of an ER and the air ambulance delays might have affected her husband’s outcome. After being flown to Kansas City, Robert Findley died.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

This App Aims To Save New Moms’ Lives

Mahmee CEO Melissa Hanna (right) and her mother Linda Hanna (left) co-founded the company in 2014. Linda’s more than 40 years of clinical experience as a registered nurse and certified lactation consultant helped them understand the need, they say.

Keith Alcantara/Mahmee

hide caption

toggle caption

Keith Alcantara/Mahmee

The U.S. has the worst rate of maternal deaths in the developed world. Thousands of women — especially black women — experience pregnancy-related complications just before or in the year after childbirth, and about 700 women die every year from them, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Tech startup Mahmee wants to change that. Founded in 2014, the company works to help women during the weeks and months after they’ve given birth, via a mobile app that’s designed to better connect new moms with health care and support, offering tools like surveys to assess their postpartum emotional and physical health. The goal? To reduce maternal deaths and complications.

Mothers can sign up on their own and get access to a team of experts including maternity coaches, nutritionists and lactation coaches — and if their health care providers are connected to the system, they can share information with them. To date, the company has more than 1,000 providers and organizations in its network.

In July, the app received $3 million in new funding to grow its team — a portion of which comes from Serena Williams, the tennis star who made headlines last year after she almost died shortly after giving birth to her daughter. Williams’s experience helped shine a light on maternal health concerns, particularly among black women.

Melissa Hanna is CEO of Mahmee and a co-founder, along with her mother, Linda Hanna. Linda is also a longtime nurse and lactation consultant. NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro spoke to mother and daughter about their app and how they are addressing what the two see as a gap in postpartum health care.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tell us how you came up with Mahmee?

Melissa: The idea for Mahmee came about from watching my mom work in this field for years and years and realizing that there was a limited set of tools available to professionals like herself to create the impact that she wanted to have on mothers’ and babies’ lives. And after watching her build out very successful programs for hospitals and health systems and all sorts of different experiences in the inpatient setting, we started talking about what could be done in the outpatient setting when patients are home with their families.

What are some of the common complications new mothers might face — and how could Mahmee help them?

Melissa: In the past 12 months, we’ve had patients who’ve experienced severe blood loss and postpartum hemorrhaging. We’ve worked with families and with mothers that are experiencing prenatal anxiety and supported them in preparing for their childbirth experience in the hospital. There have been patients who have experienced postpartum depression; in some cases, some very severe postpartum psychosis symptoms.

One case in particular comes to mind. A patient who was experiencing suicidal ideations and hadn’t reached out to anyone for help yet…she wasn’t sure if this was a normal part of being a new mom. She had a 2-week-old baby. After taking the postpartum depression survey that was available to her on her Patient Dashboard, [she] scored really high and [was] immediately flagged for additional assistance. And so Mahmee was able to step in and engage with her, verify these symptoms, and immediately escalate this to the OB-GYN’s attention who had no idea she’d been struggling.

Studies have shown that women of color are three times more likely to die of childbirth complications than white women in the U-S. Why is that, and what is Mahmee trying to do to close that gap?

Melissa: What we’re seeing now is the crisis of maternity and infant health care come to the surface because the stats around black mother and black infant mortality and morbidity are so inexcusable. There’s a huge discrepancy in how patients are cared for.

I think that a very important part of this whole story that often gets overlooked is how broken the overall system is, and how fragmented it is for any parent who’s trying to navigate this process with a number of different providers [across] different health ecosystems. You’ve got your OB-GYN taking care of Mom, the pediatrician taking care of baby, and a number of other professionals who are often out-of-network for new families. And then you add into that a layer of systemic racism and bias …it just becomes these insurmountable odds for families [of color].

Linda: One of the biggest drawbacks for [this population is] that they don’t believe anybody is going to listen or actually care. We actually do care. We want to know how you’re feeling and we want to be able to step in when somebody even reports just a feeling that they’re having. We don’t tell people, “oh, that’s normal, or that’s a common feeling,” but actually address what they’re feeling.

For hospitals and health care providers that sign up, how does it work? Does Mahmee offer some sort of bias training to its physicians?

Melissa: At Mahmee, we practice what we call “culturally competent care,” which means that from day one our team is getting trained on how to actively listen to families’ concerns, and specifically to read between the lines of the things that are being shared by new mothers. Patients are concerned that they’re not going to be believed anyway if they express what’s really going on. And so at Mahmee we are very conscious of the fact that this is what’s happening around the country, and this is something that patients are living with every day. It means that we have to overcome that by providing a degree of care that is above and beyond … really coming to patients where they’re at.

How did Serena Williams become an investor?

Melissa: We connected with Serena Williams through Arlan Hamilton, who’s a longtime investor and advocate for Mahmee.

Linda: I insisted that I wouldn’t actually take money or have anybody investing who didn’t really understand myself and Melissa first. And I’d like to meet everyone. She agreed, and I think she’s a very busy woman. Then she saw us on the screen — we were doing a video call — and she saw that I was a Caucasian woman and my daughter was a mixed race girl, and she almost started crying. Then we got the privilege of meeting her in person, which was incredible.

Creative Recruiting Helps Rural Hospitals Overcome Doctor Shortages

The wide-open spaces of Arco, Idaho, appeal to some doctors with a love of the outdoors.

Thomas Hawk/Flickr

hide caption

toggle caption

In the central Idaho community of Arco, where Lost Rivers Medical Center is located, the elk and bear outnumber the human population of a thousand. The view from the hospital is flat grassland surrounded by mountain ranges that make for formidable driving in wintertime.

“We’re actually considered a frontier area, which I didn’t even know was a census designation until I moved there,” says Brad Huerta, CEO of the hospital. “I didn’t think there’s anything more rural than rural.”

There are no stoplights in the area. Nor is there a Costco, a Starbucks or — more critically — a surgeon. With 63 full-time employees, the hospital is the county’s largest employer, serving an area larger than Rhode Island.

Six years ago, the hospital declared bankruptcy and was on the cusp of closing. Like many other rural hospitals, it was beset by challenges, including chronic difficulties recruiting medical staff willing to live and work in remote, sparsely populated communities. A hot job market made that even harder.

But against the odds, Huerta has turned Lost Rivers around. He trimmed budgets, but also invested in new technologies and services. And he focused on recruitment.

Kearny County Hospital CEO Benjamin Anderson, left, and Bradley Huerta, CEO of Lost Rivers Medical Center.

Courtesy of Becky Chappel and Bradley Huerta

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Becky Chappel and Bradley Huerta

He targeted older physicians — semiretired empty nesters willing to work part time. He also lured recruits using the area’s best asset: the great outdoors.

“You like mountain climbing, we’re gonna go mountain climbing,” says Huerta, who also uses his local connections to take recruits and their families on ATV tours or flights on small planes, if they’re interested. “The big joke in health care is you don’t recruit the person you recruit their spouse.”

Huerta’s approach has paid off; Lost Rivers is now fully staffed.

Recruitment is a life or death issue, not just for patients in those areas, but for the hospitals themselves, says Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association. Over the last decade, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed, he says, and over the next decade, another 700 more are at risk.

“Keeping access to health care in rural America is simply a challenge no matter how you look at it, but this shortage of rural health care professionals just is an unfortunate driving issue towards more closures,” Morgan says.

And that’s affecting the health of rural communities. “Most certainly the workforce shortages in rural America are contributing towards the decreased life expectancy that we’re seeing in rural America,” he says.

For some rural hospitals, that dire need is the basis of their recruiting pitch: Come here. Make a difference.

That is the crux of Benjamin Anderson’s approach at Kearny County Hospital in the southwestern Kansas town of Lakin.

With a population of about 2,000, last year The Washington Post ranked Lakin one of the country’s most “middle of nowhere” places.

Anderson says he’s found success targeting people motivated by mission over money: “A person that is driven toward the relief of human suffering and the pursuit of justice and equity.”

It’s not that the hospital ignores practical concerns. Hospital staff often house-hunt for recruits, or manage home renovations for incoming workers. Anderson, who isn’t a doctor, also personally babysits the children of his staff, because Lakin lacks nanny services.

“I mean as a CEO I do a lot of different things, but that’s among the most important, because it communicates we love you,” Anderson says. “We’re gonna live in a remote area but we’re gonna live here and support each other.”

But the cornerstone of the hospital’s recruitment pitch is 10 weeks of paid sabbatical a year, which allows time for doctors to serve on medical missions overseas.

Anderson says he came to appreciate the draw of that after a mentor told him, “Go with them and see what motivates them; see why they would want to go there.” Anderson did. It not only changed his life, he says, “I realized that in rural Kansas we have more in common with rural Zimbabwe than we do with Boston, Mass.”

It’s a compelling enough draw that every couple of weeks, Anderson gets a call from physicians saying they want to work in Lakin, despite its remoteness.

One of those callers was Dr. Daniel Linville. He’d read about Kearny County Hospital and its sabbaticals in a magazine article during medical school. Last fall, Linville joined the hospital, having done mission work since childhood in Ecuador, Kenya and Belize.

He says he and his physician wife were also drawn to the surprisingly diverse population Kearny County Hospital serves, including immigrants from Somalia, Vietnam, Laos and Guatemala. In that sense, says Linville, every day feels like an international medical mission, requiring everything from delivering babies to treating dementia.

But life in Lakin also been an adjustment.

“Now that we’ve been out here practicing for a little bit, we realize exactly how rural we are,” Linville says. It’s not just that same-day shipping takes four days; transferring a patient to the next biggest hospital in Wichita means the ambulance and staff are gone for an 8-hour round-trip ride.

And, in an incredibly tight-knit community where he is a newcomer, he’s often reminded that patients see him as another doctor just passing through.

“We’re seen a little bit as outsiders,” Linville says. “We get asked frequently: ‘How long are you here for?’ “

I don’t know, he tells them. But for now, I’m happy.

‘Cadillac Tax’ On Generous Health Plans May Be Headed To Congressional Junkyard

The ‘Cadillac tax,’ an enacted but not yet implemented part of the Affordable Care Act, is a 40% tax on the most generous employer-provided health insurance plans — those that cost more than $11,200 per year for an individual policy or $30,150 for family coverage.

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg Creative/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg Creative/Getty Images

The politics of health care are changing. And one of the most controversial parts of the Affordable Care Act — the so-called “Cadillac tax” — may be about to change with it.

The Cadillac tax is a 40% tax on the most generous employer-provided health insurance plans — those that cost more than $11,200 per year for an individual policy or $30,150 for family coverage. It was a tax on employers, and was supposed to take effect in 2018 — but Congress has delayed implementation twice.

And the House, now controlled by Democrats, recently voted overwhelmingly — 419 to 6 — to repeal that part of the ACA entirely. A Senate companion bill is bipartisan and now has a total of 61 cosponsors — more than enough to ensure passage.

The tax was always an unpopular and controversial part of the 2010 health law, because the expectation was that employers would cut benefits to avoid the tax. Still, ACA backers initially said the tax was necessary to help pay for the law’s nearly $1 trillion cost and help stem the use of what was seen as potentially unnecessary care.

In the ensuing years, however, public opinion has shifted decisively, as premiums and out-of-pocket costs for patients have soared. Now the biggest health issue is not how much the nation is spending on health care, but how much individuals are.

“Voters deeply care about health care, still,” says Heather Meade, a spokeswoman for the Alliance to Fight the 40, a coalition of business, labor and patient advocacy groups urging repeal of the Cadillac tax. “But it is about their own personal cost and their ability to afford health care.”

Stan Dorn, a senior fellow at Families USA, recently wrote in the journal Health Affairs that the backers of the ACA thought the tax was necessary to sell the law to people concerned about its price tag, and to cut back on overly generous benefits that could drive up health costs. But transitions in health care, such the increasing use of high-deductible plans in the workplace, make that argument less compelling, he said.

“Nowadays, few observers would argue that [employer-sponsored insurance] gives most workers and their families excessive coverage,” he wrote.

The possibility that the tax might be implemented has been “casting a statutory shadow over 180 million Americans’ health plans, which we know, from HR administrators and employee reps in real life, has added pressure to shift coverage into higher-deductible plans,” says Rep. Joe Courtney, D-Conn. And that, he adds, “falls on the backs of working Americans.

Support or opposition to the Cadillac tax has never broken down cleanly along party lines. For example, economists from across the ideological spectrum supported its inclusion in the ACA, and many continue to endorse it.

“If people have insurance that pays for too much, they don’t have enough skin in the game. They may be too quick to seek professional medical care. They may too easily accede when physicians recommend superfluous tests and treatments,” wrote N. Gregory Mankiw, an economics adviser in the George W. Bush administration, and Lawrence Summers, an economic aide to President Barack Obama, in a 2015 column in the New York Times. “Such behavior can drive national health spending beyond what is necessary and desirable.”

At the same time, however, the tax has been bitterly opposed by organized labor, a key constituency for Democrats. “Many unions have been unable to bargain for higher wages, but they have been taking more generous health benefits, instead, for years,” says Robert Blendon, a professor at the Harvard School of Public Health who studies health and public opinion.

Now, unions say, those benefits are disappearing, with premiums, deductibles and other cost-sharing moves are rising as employers scramble to stay under the threshold for the impending tax.

“Employers are using the tax as justification to shift more costs to employees, raising costs for workers and their families,” said a letter to members of Congress from the Service Employees International Union in July.

Deductibles in health insurance plans have been rising for a number of reasons, the possibility of the tax among them. According to a 2018 survey by the federal government’s National Center for Health Statistics, nearly half of Americans under age 65 (47%) had high-deductible health plans. Those are plans that have deductibles of at least $1,350 for individual coverage or $2,700 for family coverage.

It’s not yet clear if the Senate will take up the House-passed bill, or one like it.

The senators leading the charge in that chamber — Mike Rounds, R-S.D., and Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., — have already written to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to urge him to bring the bill to the floor following the House’s overwhelming vote.

“At a time when health care expenses continue to go up, and Congress remains divided on many issues, the repeal of the Cadillac Tax is something that has true bipartisan support,” their letter said.

Still, there is opposition to repealing the tax. A letter to the Senate July 29 from health care economists and others argued that implementing it, instead, would “help curtail the growth of private health insurance premiums by encouraging employers to limit the costs of plans to the tax-free amount.” That letter also pointed out that repealing the tax “would add directly to the federal budget deficit, an estimated $197 billion over the next decade, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.”

If McConnell does bring the bill up, there is little doubt it will pass, despite support for the tax from economists and budget watchdogs.

“When employers and employees agree in lockstep that they hate it, there are not enough economists out there to outvote them,” says former Senate GOP aide Rodney Whitlock, now a health care consultant.

Harvard professor Blendon agrees. “Voters are saying, ‘We want you to lower our health costs,'” he says. The Cadillac tax, at least for those affected by it, would do the opposite.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, and is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Newark’s Drinking Water Problem: Lead And Unreliable Filters

A Newark, N.J., resident carries a case of bottled water distributed Monday at a recreation center. The Environmental Protection Agency said residents shouldn’t rely on water filters the city gave out to address lead contamination.

Kathy Willens/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Kathy Willens/AP

Lead contamination in the drinking water in Newark, N.J., is not a new problem, but the city’s fleeting solution has become newly problematic.

Officials in Newark, the state’s largest city, which supplies water to some 280,000 people, began to hand out bottled water Monday.

That’s because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has concerns about water filters that the city distributed to residents.

Last fall, Newark gave out more than 40,000 water filters, even going door to door to reach families with lead service lines. The toxin is believed to have leached into drinking water through the old pipes between water treatment plants and people’s homes. Free filters and cartridges would remove 99% of lead, the city of Newark said.

But recent test results introduced an element of doubt about that claim. A regional administrator at the EPA sent a letter Friday to city officials, saying tests on two homes suggested the filters “may not be reliably effective.” Samples showed the filtered drinking water had lead levels exceeding 15 parts per billion, which is the federal and state standard, EPA regional administrator Peter Lopez said.

City leaders acknowledged the problem in the days that followed.

Gov. Phil Murphy and Mayor Ras Baraka, both Democrats, said in a joint statement that they were prepared to do “everything the City needs,” including doling out free water bottles.

They added that the city and state will need assistance from the federal government to provide and distribute the bottles.

In January, Baraka urged President Trump to help protect Newark’s fraught water infrastructure systems instead of funding a wall at the U.S. Southern border to deter migrants. “It will cost an estimated $70 million to replace the lead service lines in Newark,” Baraka said in a letter.

A spokesperson for Sen. Cory Booker, a former mayor of Newark and presidential candidate, told NPR that the senator had made efforts to address New Jersey’s water problem. “We’ll be sending a letter to the [EPA]” later on Tuesday with other federal lawmakers in New Jersey, “urging the EPA to help the city and state with distributing bottled water to its residents,” spokesperson Kristin Lynch said.

Booker also introduced the Water Infrastructure Funding Transfer Bill in May. He said the measure would give states flexibility to fund infrastructure projects. That bill’s passage was blocked in Congress, Lynch said.

Newark resident Emmett Coleman told USA Today that he spent an hour on Monday waiting for two cases of bottled water. “In the senior building, it’s bad,” he said. “All of us are sick or have problems, and we can’t drink the water. And the filters aren’t working.”

The distribution scene would have looked familiar to residents in Flint, Mich., who suffered from years of contaminated drinking water and subsisted on bottled water. And like Flint, Newark has a high poverty rate — about 28%, compared with the national rate of 12.3% in 2017, according to the Census Bureau.

About 15,000 homes in Newark had lead service lines that brought contaminated water to their residences, the city said in a statement. It advised residents to take precautions, including getting children’s blood tested for lead exposure.

The city will continue to test both the filters and filtered water.

The Natural Resources Defense Council and Newark Education Workers Caucus sued Newark and New Jersey state officials last year, accusing them of violating the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. “If it takes filing a lawsuit to end violations of federal drinking water law, we’ll do it,” Claire Woods, an attorney with NRDC, said at the time. That lawsuit is pending.

Authorities say there is no safe level of lead exposure. Pregnant women and children are the most vulnerable groups, with dangers that include fertility problems, damage to organs and cognitive dysfunction.