Dialysis Firm Cancels $524,600.17 Medical Bill After Journalists Investigate

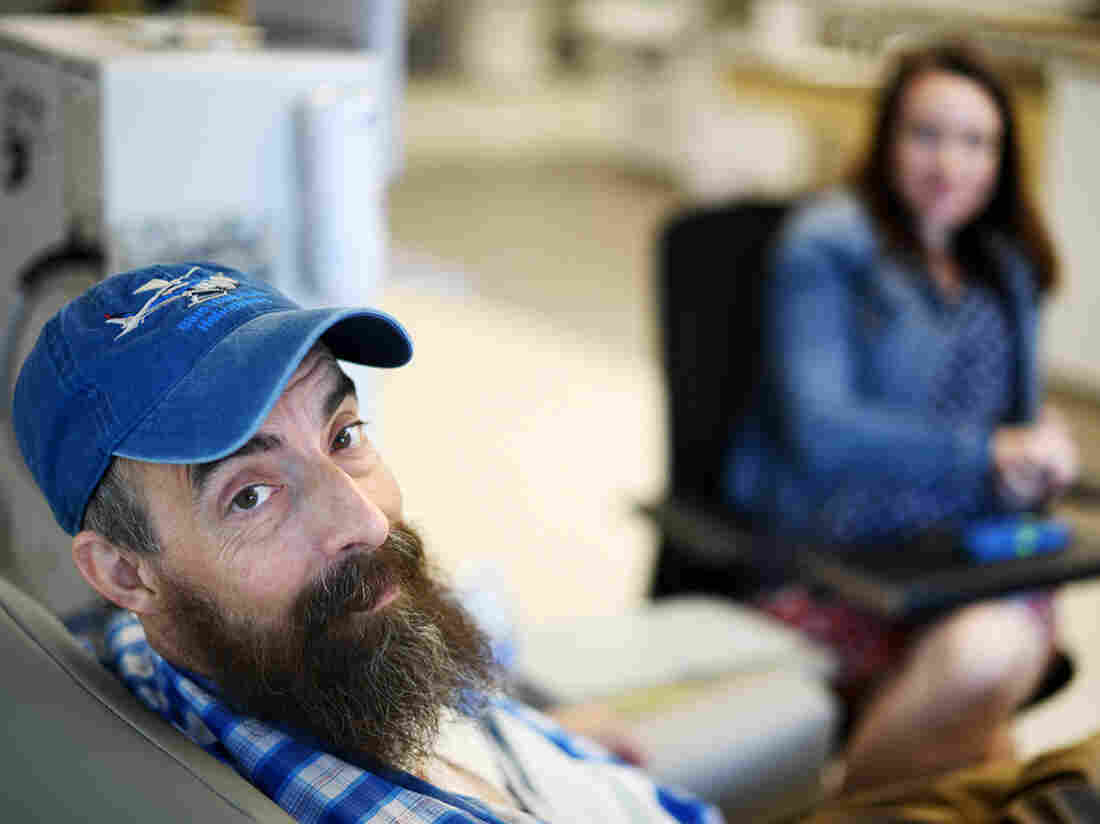

Sovereign Valentine, a personal trainer in Plains, Mont., needs dialysis for his end-stage renal disease. When he first started dialysis treatments, Fresenius Kidney Care clinic in Missoula charged $13,867.74 per session, or about 59 times the $235 Medicare pays for a dialysis session.

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

Fresenius, one of the two largest dialysis providers in the U.S., has agreed to waive a $524,600.17 bill for a man who received 14 weeks of dialysis at a clinic in Montana.

NPR, Kaiser Health News, and CBS This Morning told Sovereign Valentine’s story this week, as part of the “Bill of the Month” series, a crowdsourced investigation that seeks to understand the exorbitant health care bills faced by ordinary Americans.

On Thursday, a representative from Fresenius told Sovereign’s wife, Dr. Jessica Valentine, that the company would waive their unpaid bill. Instead, they will be treated as in-network patients, and Fresenius will seek to negotiate with their insurer a rate higher than what the insurer has already paid. The Valentines are responsible only for their $5,000 deductible, which Sovereign, who goes by “Sov,” has already hit for the year. That leaves them with $0 left to pay on their in-network deductible.

“It’s a huge relief,” Sov said. “It allows me to put more energy back into just taking care of my health and not having stress hormones raging.” Sov said he hopes his experience will shed light on the problem of balance billing and help other patients in similar situations.

A 50-year-old personal trainer, Sov was diagnosed with kidney failure in January and sent for dialysis at a Fresenius clinic 70 miles from his home in rural Plains, Mont. A few days later, Sov and Jessica learned that the clinic was out-of-network and that they would be required to pay whatever their insurer didn’t cover.

The Valentines initially could not find an in-network option, and Sov needed dialysis three times a week to survive. After he underwent 14 weeks of dialysis with Fresenius, the couple received a bill for $540,841.90. Their insurer, Allegiance, paid $16,241.73, about twice what Medicare would have paid. Fresenius billed the couple the unpaid balance of $524,600.17 — an amount that is more than the typical cost of a kidney transplant.

Fresenius charged the Valentines $13,867.74 per dialysis session, or about 59 times the $235 Medicare pays for a dialysis session.

Fresenius spokesman Brad Puffer said that the Valentines should always have been treated as in-network patients because their insurer, Allegiance, is a subsidiary of Cigna, which has a contract with the dialysis company. Under this contract, Fresenius would have been paid a higher rate than what Allegiance paid. The Valentines, he said, were caught in the middle of a contract dispute between the companies.

“In the future, we pledge to better identify situations where we believe the insurer has incorrectly classified one of our facilities as being out of network,” Puffer said in a statement. “This will allow us to address the matter directly with the insurer in the first instance, without them placing the patient in the middle.”

Allegiance declined to comment for this story. Jessica Valentine questioned whether they may owe an out-of-network deductible and is waiting to hear what her insurer says about that.

Like her husband, Jessica is relieved that their bill seems to be resolved but worried that other people with bills like theirs might not be so lucky. She’s also grateful for all the attention their story has garnered. Montana Sen. Jon Tester’s office and their hospital’s insurance broker both offered to advocate for them. “And a nephrologist from Pennsylvania called me at work and expressed outrage and said she forwarded on our story to the medical director of Fresenius on our behalf,” Jessica wrote in an email.

Now that his bill has been resolved, Sov said he’ll be focusing on the next step in battling his kidney disease: a transplant. “I can just save my energy for that,” he said.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by NPR and Kaiser Health News that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

How To Bring Cancer Care To The World’s Poorest Children

Computer illustration of malignant B-cell lymphocytes seen in Burkitt’s lymphoma, the most common childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

It’s one of the great achievements of oncology: with advances in treatment, cure rates for children with cancer in North America now exceed 80%, up from 10% in the 1960s.

Yet for kids across the developing world, the fruits of that progress remain largely out of reach. In low- and middle-income countries, restrictive access to affordable treatment, a shortage of cancer specialists and late diagnosis dooms more than 80% of pediatric patients to die of the same illnesses.

That’s one measure of what’s known as the “global cancer divide“— the vast and growing gap in access to quality cancer care between wealthy and poorer countries, and the suffering and death that occurs disproportionately in the latter.

Nowhere is that divide more pronounced than among children, and it’s driven in large part, experts say, by perceptions of pediatric cancer care as too costly and too complicated to deliver in low-resource settings. Those assumptions, they say, prevent policymakers from even considering pediatric oncology when setting national health priorities.

But one hospital in Rwanda is rewriting that narrative.

Built and operated by the Ministry of Health and the Boston-based charity Partners In Health, the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence is unique in the region: a state-of-the-art medical facility providing the rural poor with access to comprehensive cancer care. And a new study shows that Butaro’s pediatric cancer patients can be cared for, and cured, at a fraction of the cost in high-income countries.

“There’s this myth that treating cancer is expensive,” says Christian Rusangwa, a Rwandan physician with Partners In Health who worked on the study. “And that’s because the data is almost all from high-income countries.”

Published in 2018 in the Journal of Global Oncology, the study showed that for patients at Butaro with nephroblastoma and Hodgkin lymphoma, two common childhood cancers, a full course of treatment, follow-up and social support runs as little as $1,490 and $1,140, respectively.

Much of the savings, the authors report, comes from the low cost of labor, which for the entire cancer center amounted to less than the average annual salary for one oncologist in the United States. They also cite strong partnerships with Harvard and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, whose Boston-based specialists volunteer their expertise on difficult patient cases via weekly video conferences with Butaro’s general practitioners.

“Most people don’t think about childhood cancer in terms of return on investment,” says Nickhill Bhakta, a pediatric oncologist with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, which has put in place similar partnerships with institutions in Singapore and China. “But there’s a growing body of literature showing that, for governments, treatment is surprisingly cost-effective.”

Bhakta says some of the most compelling evidence for the cost-effectiveness of care in poor countries comes from Uganda, where in March, researchers reported remarkably low costs of treating Burkitt’s lymphoma, or BL. The most common childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa, BL is rapidly fatal, often within weeks. Yet when treated promptly, intensively and with supportive care, more than 90% of children survive the disease.

Worldwide, childhood cancers are relatively rare. But as Bhakta and colleagues reported in February in The Lancet Oncology, they’re a far bigger problem than previously believed. Close to half of all children with cancer go undiagnosed and untreated, they found, suggesting that the already low survival for these cancers in low- and middle-income countries “is probably even lower.”

“The naysayers will say, ‘we don’t have pediatric oncologists in Africa, how would we possibly address this problem?’ ” says Felicia Knaul, a professor of public health at the University of Miami. “And that’s why partnership models, like those supported by Dana Farber and St. Jude, are so important — they’ve shown that you can bridge that gap and have a tremendous impact.”

In 2009, Knaul, then director of the Harvard Global Equity Initiative, led a push to expand cancer care across the developing world, where a growing burden of disease had garnered little attention globally. “We challenge the public health community’s assumption that cancers will remain untreated in poor countries,” she and colleagues wrote in a 2010 “call to action” published in The Lancet, noting “similarly unfounded arguments” against the provision of HIV treatment.

In the early 2000s, more than 20 million people were living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, yet fewer than 50,000 had access to antiretroviral therapy. Though the life-saving drugs were, by then, widely available in the U.S., skeptics warned that treatment in Africa wouldn’t be cost-effective.

Prevention, they asserted, was the only feasible way forward. “The two most important interventions are monogamy and abstinence,” Andrew Natsios, then head of the U.S. Agency for International Development, told reporters in 2001. “The best thing to do is behave yourself.”

Two decades later, echoes of that attitude reverberate in the global cancer divide; even as cancer rates continue to climb across the developing world, low and middle-income countries account for just 5% of global spending on the disease.

Still, recent years have seen important gains.

In 2017, the World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization’s decision-making body, adopted a resolution on cancer that for the first time urged its member states to address childhood cancers. And in 2018, St. Jude and the WHO launched the Global Initiative on Childhood Cancer, a five-year, $15 million partnership aimed at aimed at ensuring that all children with cancer can access high-quality medicines. Their goal: to cure at least 60% of children with the six most common types of cancer by 2030.

“Here in the U.S., it was the suffering of children with acute leukemia that drove Sidney Farber to develop our first real chemotherapy drug,” said Meg O’Brien, vice president for global cancer treatment at the American Cancer Society. “I don’t think Dr. Farber or any of the tens of thousands of oncologists, nurses or scientists who have worked in cancer research or treatment in the years since would be content to see that what we consider one of our greatest triumphs in the battle against cancer has yet to reach children in low- and middle-income countries.”

Patrick Adams is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta, GA. Find him on Twitter at @jpatadams

Litigation Over America’s Opioid Crisis Is Heating Up

NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly speaks with lawyer Mike Moore, who is representing several states, counties and cities that are suing opioid manufacturers.

Allergan Recalls Textured Breast Implants Linked To Rare Type Of Cancer

Courtesy of Jeff Weiner/Allergan

Allergen has announced a global recall of textured breast implants that are linked to a type of cancer, at the request of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Biocell saline-filled and silicone-filled textured breast implants and tissue expanders will no longer be distributed or sold in any market where they are currently available,” according to a company statement Wednesday.

The FDA said in a statement that while the overall incidence of a rare type of lymphoma appears to be low, it asked Allergan to initiate the Biocell implant recall “once the evidence indicated that a specific manufacturer’s product appeared to be directly linked to significant patient harm, including death.”

The agency does not recommend that people who already have the textured implants get them removed unless there are symptoms or problems, but it is providing information for patients and providers to consider.

The FDA said it requested the recall after a “significant increase” in cases of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), a type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Since its previous report in February, there have been 116 new cases and 24 deaths.

“Based on new data, our team concluded that action is necessary at this time to protect the public health,” said FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy.

Overall, according to the FDA, there have been 573 cases of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) and 33 patient deaths worldwide. The agency said 481 of the cases are attributed to the Allergan implants, and that among the deaths “12 of the 13 patients for which the manufacturer of the implant is known, are confirmed to have an Allergan breast implant at the time of their BIA-ALCL diagnosis.”

Based on the latest data, the FDA said, “our analysis demonstrates that the risk of BIA-ALCL with Allergan BIOCELL textured implants is approximately six times the risk of BIA-ALCL with textured implants from other manufacturers marketing in the U.S.”

The FDA first reported on the connection between implants and the rare cancer back in 2011, and Abernathy said the agency has continued to monitor reports in databases and patient registries and scientific studies pointing to risks.

Nearly 314,000 people received breast implants in the U.S. in 2018, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. The group’s report does not distinguish between textured implants and other kinds.

“In the United States, the use of textured implants is much less common than the use of textured implants in Europe and Asia,” said plastic surgeon Daniel Maman, who is in private practice in New York and an assistant professor at Mount Sinai.

It’s not clear whether the texturing is actually responsible for the cancer or is just associated with a higher incidence of the disease. But Maman and others say the surface can interact with the surrounding scar tissue that the body forms as an immune response to the implant.

“It’s that response that is believed to cause the formation of the lymphoma,” Maman said, noting that he only uses smooth, round implants. However, he said that overall, breast implants “are exceedingly safe.”

The FDA’s action Wednesday is a change in course from a few months ago when advisers concluded there was a lack of scientific certainty about the health risks that breast implants pose to the millions of women who have them.

At the time, as NPR’s Patti Neighmond reported, “most members of the panel said there’s not enough evidence yet to rush textured implants off the market and that larger, longer-term studies are needed.”

Allergan said Wednesday that healthcare providers should no longer implant the Biocell implants and tissue expanders and that unused products should be sent back to the company. It said it would also work with customers about how to return unused products.

From Insomnia To Sexsomnia, Unlocking The ‘Secret World’ Of Sleep

Different parts of the brain aren’t always in the same stage of sleep at the same time, notes neurologist and author Guy Leschziner. When this happens, an individual might order a pizza or go out for a drive — while technically still being fast asleep.

Frederic Cirou/PhotoAlto/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Frederic Cirou/PhotoAlto/Getty Images

We tend to think of being asleep or awake as an either-or prospect: If you’re not asleep, then you must be awake. But sleep disorder specialist and neurologist Guy Leschziner says it’s not that simple.

“If one looks at the brain during sleep, we now know that actually sleep is not a static state,” Leschziner says. “There are a number of different brain states that occur while we sleep.”

As head of the sleep disorders center at Guy’s Hospital in London, Leschziner has treated patients with a host of nocturnal problems, including insomnia, night terrors, narcolepsy, sleep walking, sleep eating and sexsomnia, a condition in which a person pursues sexual acts while asleep. He writes about his experiences in his book The Nocturnal Brain.

Leschziner notes that the different parts of the brain aren’t always in the same stage of sleep at the same time. When this happens, an individual might order a pizza or go out for a drive — while technically still being fast asleep.

“Sometimes these conditions sound very funny,” Leschziner says. “But on other occasions they can be really life changing, resulting in major injury or, as one of the cases that I described in the book, in a criminal conviction.”

Interview highlights

On what we know about recall after a sleepwalking episode

We used to think that people don’t really remember anything that occurs in this stage. That seems to relate to the fact that the brain in parts is in very deep sleep whilst in other parts is awake. What we have learned over the last few years is that actually quite a lot of people have some sort of limited recall. They don’t necessarily remember the details of all the events or indeed the entirety of the event, but sometimes they do experience little snippets. … On one occasion, [a patient] dragged his girlfriend out of bed in the middle of the night because he thought that a tsunami was about to wash them away, and those kinds of events with strong emotional context are often better remembered.

On how sleepwalking demonstrates the brain can be in multiple sleep stages at once

Certain parts of the brain can remain in very deep sleep … [such as] the frontal lobes, which are the seats of our rational thinking or planning or restricting on normal behaviors, whereas other parts of the brain can exhibit electrical activity that is really akin to being wide awake. So, in particular, the parts of the brain that [can seem to remain awake] are [the ones] responsible for emotion, an area of the brain called the limbic system, obviously the parts of the brain that are responsible for movement. And it’s this dissociation, this disconnect between the different parts of the brain in terms of the sleep stages, that actually give rise to these sorts of behaviors.

On what causes sleepwalking

We know that sleepwalking and these related conditions seem to run very strongly in families. So there seems to be some sort of genetic predisposition to being able to enter into this disconnected brain state, and we know that anything that disrupts your sleep if you have that genetic predisposition can give rise to these behaviors. So, for example, I’ve seen people who have had non-REM parasomnia events [such as sleepwalking] triggered by the fact that they sleep in a creaky bed and their bed partner rolled over [or] sometimes a large truck [drove] past in the street outside the bedroom.

But there are also internal manifestations, internal processes that can give rise to these partial awakenings. So, for example, snoring or, more severe than snoring, sleep apnea, where people stop breathing in their sleep … anything that causes a change in the depth of sleep in people who are predisposed to this phenomenon of being in multiple sleep stages at the same time can give rise to these behaviors.

On sleep apnea

Sleep apnea describes the phenomenon of our airway collapsing down in sleep. … Our airway is essentially a floppy tube that has some rigidity, some structure to it as a result of multiple muscles. And as we drift off to sleep, those muscles lose some of their tension, and the airway becomes a little bit more floppy. Now when it’s a little bit floppy and it reverberates as we breathe in during sleep, that will result in snoring — the reverberation of the walls of the airway result in the noise.

But in certain individuals, the airway can become floppy enough or is narrow enough for it to collapse down and to block airflow as we’re sleeping. It’s normal for that to occur every once in a while for everybody, but if it occurs very frequently, then what happens is that sleep can be disrupted sometimes 10, sometimes 20, sometimes even 100 times an hour, because as we drift off to sleep, the airway collapses down, our oxygen levels drop, our heart rate increases, our brain wakes up again and our sleep is essentially being disrupted. …

We are now aware that obstructive sleep apnea has a range of long-term implications on our health in terms of high blood pressure, in terms of risk of cardiovascular disease, risk of stroke, impact on cognition and mental clarity. And there is now an emerging body of evidence to suggest that actually obstructive sleep apnea may be a factor in the development of conditions like dementia.

On the importance of having positive associations with your bed

If you’re a good sleeper, you tend to associate being in bed with being in that place of comfort, that place where you go and you … feel cozy and you drift off to sleep and you wake up in the morning feeling wide awake and refreshed. But for people with insomnia, they often associate bed with great difficulty getting off to sleep, with the dread of the night ahead, with the fact that they know that when they wake up in the morning they will feel horribly unrefreshed and unrested. And so the environment that we normally would associate with sleep becomes an instrument of torture for them. And so a lot of the advances that have been made in this area about treating insomnia are really directed towards breaking down those negative associations that people have with their sleeping environment if they have insomnia and rebuilding positive associations. So trying to utilize the brain’s own mechanisms for drifting off to sleep and trying to reduce the anxiety surrounding sleep in order to reestablish a normal sleep pattern.

On the problem with taking benzodiazepines and Ambien for insomnia

There has been a bit of a sea change in the last few years away from these drugs. We know that these drugs [are] sedatives. So the first thing to know is that they do not mimic normal sleep. They’re associated with some major problems. So some of these drugs are, for example, associated with an increased risk of road traffic accidents in the morning, because of a hangover effect. They’re associated with an increased risk of falls in the elderly, for example. And we know that people can develop a dependency on these drugs and can also habituate, by which I mean that they require ever-increasing doses to obtain the same effect.

In the long term, there are now some signals coming out of the work that is being done around the world that suggest that some of these drugs are actually associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. And whilst that story is not completely understood — and it may be that people who have insomnia in themselves are predisposed to dementia or actually that insomnia may be a really early warning sign of dementia — [it] certainly gives us cause for concern that perhaps we shouldn’t be using these drugs quite as liberally as we have done historically. And so therefore the switch to behavioral approaches, approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, has been really driven by some of these concerns.

On his recommendation that you read before bed

Provided you are not reading on a tablet or a laptop, [and instead an] old-style analog book, I would highly recommend. It’s a good way of reducing your light exposure. Keeping your mind a little bit active so that you’re not concentrating on the prospect of having to drift off to sleep until you’re really tired. It’s a very good way of keeping your mind occupied.

Sam Briger and Mooj Zadie produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz and Molly Seavy-Nesper adapted it for the Web.

Missouri Firm With Silicon Valley Ties Faces Medicare Billing Scrutiny

The same steep growth and use of big data that attracted venture capital cash to firms that administer Medicare Advantage plans have led to scrutiny of the firms by government officials. Federal audits estimate such plans nationwide have overcharged taxpayers nearly $10 billion annually.

123light/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

123light/Getty Images

In many ways, Essence Group Holdings Corp. is a homegrown health care success story.

Founded in St. Louis, it has grown into a broader company backed by a major Silicon Valley investor. Essence now boasts Medicare Advantage plans for seniors with some 60,000 members in Missouri and across the Mississippi River in Illinois. It ranks among the city’s top 35 privately held companies, according to the St. Louis Business Journal. And market research firm PitchBook Data values the company at over $1.64 billion.

But a recent audit by the federal Health and Human Services inspector general, along with a whistleblower lawsuit, have put the St. Louis health care standout under scrutiny. Medicare officials also are conducting a separate audit of Essence.

The same growth and use of big data that attracted venture capital cash are getting a renewed look from government officials who estimate that Medicare Advantage plans nationwide overcharge taxpayers nearly $10 billion annually.

The April audit of Essence — the first in a series of upcoming audits scrutinizing some Medicare Advantage plans across the United States — revealed that the St. Louis company could not substantiate fees for dozens of patients diagnosed with stroke or depression.

The government pays privately run insurance plans like Essence using a formula called a “risk score” that is designed to pay higher rates for sicker clients and less for patients who are in good health.

“There’s great temptation to push the envelope on risk scores without the supporting documentation in the medical files, especially for depressive disorders,” says former Sen. Claire McCaskill, a Missouri Democrat who now works as a political analyst. While in office, McCaskill in 2015 called for an investigation into overbilling practices by insurers running Medicare Advantage plans.

In the Essence audit of 218 cases, HHS found dozens of instances in which the health plan reported patients had an acute stroke — meaning the patients had strokes that year — when they actually had suffered strokes only in past years.

HHS also discovered that Essence had charged Medicare for major depressive disorder diagnoses for several enrollees, but the doctors had not recommended a treatment plan — indicating the patients likely had a less severe form of depression. In five cases, HHS couldn’t find any medical records to support payments for a diagnosis of acute stroke or major depressive disorder.

Essence denied wrongdoing but agreed to refund $158,904 that Medicare paid for those patients who were reviewed in the audit, and committed to correcting any other errors.

Medicare Advantage: The next Silicon Valley frontier

Essence is part of the Medicare Advantage boom — such plans now treat more than 22.6 million U.S. seniors. That’s about 1 in 3 people on Medicare. And with that growth, the money has followed — top investors, including Google, have poured more than $1 billion into health care companies that have Medicare Advantage aspirations.

Essence’s medical technology arm, Lumeris, which helps power its Medicare Advantage plans, is key to those ambitions. And last year Lumeris received a commitment of $266 million over the next 10 years from Cerner, a leading electronic medical records firm. Cerner declined to comment for this story on its investment.

Essence, and companies like it, are venture capital darlings because they draw deeply on data mining by entities such as Lumeris to hone health care delivery and cut costs.

But Essence now finds itself in the middle of a national reckoning with the federal government, which is attempting to reduce overbilling by the Medicare Advantage industry that it says costs taxpayers up to $10 billion a year. Previous efforts to claw back such overpayments have been delayed by an onslaught of lobbying efforts by private insurers.

More overcharging alleged in lawsuit

The Missouri whistleblower suit alleges Essence, Lumeris and its local partner, Lester E. Cox Medical Centers, used data-mining software to identify patients for an “enhanced encounter” that jacked up the patients’ risk scores to boost Medicare payments.

The suit was unsealed in January after being filed in 2017 by Branson, Mo., family doctor Charles Rasmussen. In his lawsuit, Rasmussen said he worked for Cox from 2013 through August 2017 and treated more than 2,000 patients there. He and his lawyers declined to comment on the case.

After a training session on “enhanced” coding practices, one doctor wrote to Cox officials in an email that was quoted in the lawsuit. The doctor said the Essence team had used the case of an 86-year-old patient that the doctor described as “pretty healthy for looking sick on paper” as an example of a potential coding “opportunity.” The doctor wrote that the man’s care likely cost less than $2,000 a year, but Essence’s “enhanced” coding techniques could “capture around $11,000 from Medicare.”

The lawsuit alleges: “Because of this fraud, hundreds of millions of taxpayers’ dollars have been siphoned from the United States.”

The case is pending in federal court in Springfield, Mo. On July 15, a judge denied Essence and Cox’s joint motion to dismiss the case.

Essence and Lumeris denied the whistleblower’s allegations in a statement to Kaiser Health News. Lumeris spokesman Marcus Gordon says the allegations were “wholly without merit.” In the emailed statement, he says the companies would “continue to vigorously defend against these baseless claims,” adding that its programs “result in higher quality care and better health outcomes for our members.”

In a written statement, Cox Media Relations Manager Kaitlyn McConnell says the company has reviewed the allegations. “We adamantly deny them, and believe we are fully compliant with the law.” “As always, patients are our top priority,” McConnell adds, “and we will continue to focus on providing quality and compassionate health care to the communities we serve.”

St. Louis roots, ambition far beyond

Essence grew in 2007 after St. Louis physician and software designer Dr. Thomas Doerr and his venture capitalist brother, John Doerr, an early backer of Amazon and Google, invested in the company.

Good national press followed, much of it noting the company’s commitment to developing innovative medical software to improve patient care and cut costs. Neither of the Doerr brothers would comment for this article.

In December 2015, Medicare awarded Essence a 5-star rating, a coveted indicator of high-quality medical care. That helped make the plans popular for customers in Missouri, says Stacey Childs, the regional liaison for CLAIM, the state’s health insurance assistance program. She credits its A+ ranking with the Better Business Bureau and high star rankings year after year for helping create a swell of excitement when Essence expanded to the Springfield area of Missouri in 2015.

And its Lumeris-powered technology is growing nationally, including partnerships with Stanford Health Care in California and medical groups in Florida and Louisiana. It also has been deployed to other regions, bolstered by Cerner’s investment, for a joint program managing Medicare Advantage plans called the “Maestro Advantage,” according to the partnership’s website.

Coding questions

But Rasmussen, the Missouri whistleblower, alleges that Lumeris software played a role in overcharging Medicare.

The lawsuit alleges physicians were encouraged to examine high-risk patients the medical software identified for “Enhanced Encounter” appointments — even sending recommendations for some patients who were in hospice — to re-evaluate their risk scores.

Physicians were paid $100 to examine patients for each of those encounters, according to the suit. On its website, Lumeris has said those appointments create “new cash flows to enhance physician incentives and increase the level of physician engagement.”

In a statement to KHN, Taylor Griffin a spokesman for Essence said, “We compensate physicians for the substantial extra time and effort to meet with our members and gather information essential to delivering better care. It is a program designed around capturing the health status of the member and not on capturing codes.”

At least one Essence-affiliated doctor has questioned the ethics of the initiative, according to court documents. “All I have heard about since we signed on with Essence is about coding to get paid more,” the unidentified doctor alleged in an email to Cox officials. “This is doing little to enhance these patients’ care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Job Posting For Doctor At An Immigrant Detention Facility Catches People’s Attention

NPR’s Ari Shapiro speaks with Dr. Ranit Mishori, a family doctor, and a member of Physicians for Human Rights, about the job listing for a doctor to work at an ICE Processing Center.

2 Nurses In Tennessee Preach ‘Diabetes Reversal’

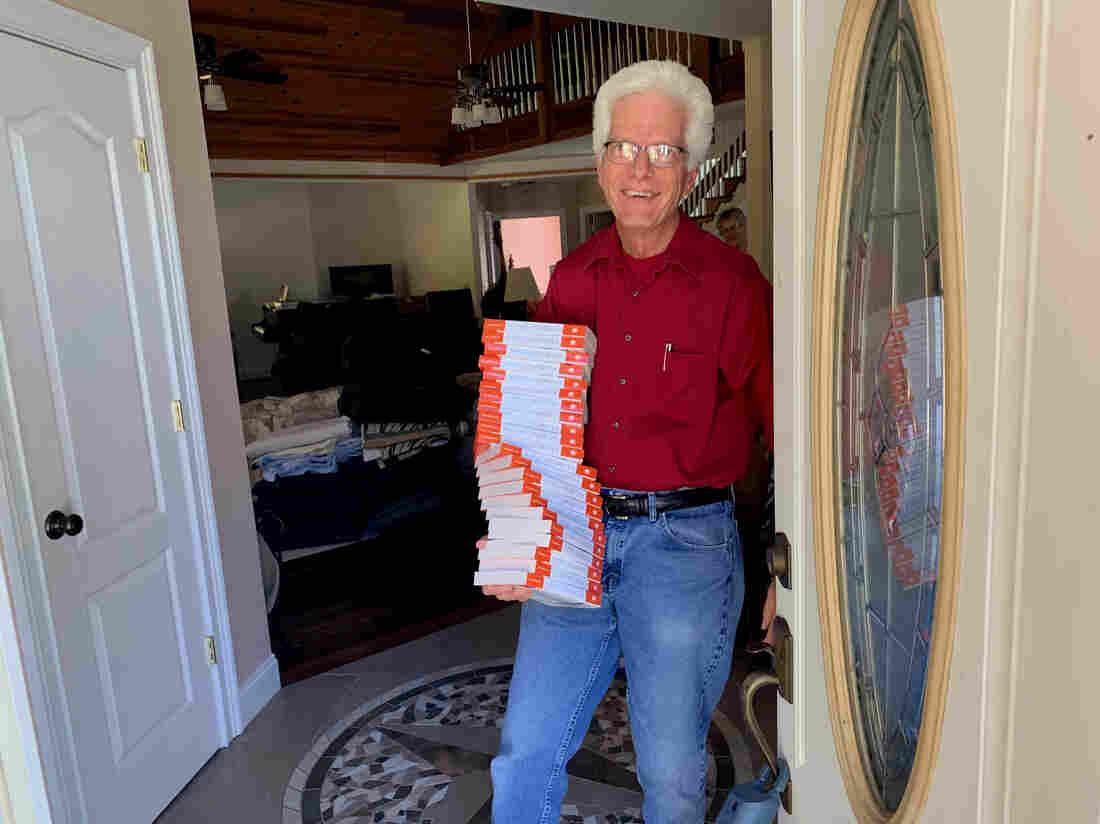

Steve Wickham, at home in Grundy County, Tenn., has developed an educational seminar with his wife, and fellow nurse, Karen, that they are using to help people with Type II diabetes bring blood sugar under control with less reliance on drugs.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

Chains, saws and old logging equipment litter the back field of Wendy Norris’ family farm, near the county seat of Altamont, Tenn. Norris used to be part of the local timber industry, and the rusted tools are relics from a time when health woes didn’t hold her back from felling hardwoods.

“I was nine months pregnant,” Norris says. “Me and my husband stayed about 10 or 15 miles in the middle of nowhere, in a tent, for a long time.”

Those outdoor adventures are just a memory now. A few years ago, as Norris turned 40, her feet started going numb. She first assumed it was from standing all day at her job at a nursing home.

“But it wasn’t,” she recalls now. “It was that neuropathy, where my [blood] sugar was high and I didn’t know it.” Norris had developed Type 2 diabetes.

Grundy County, Tenn., has a long list of public health challenges, and Type 2 diabetes tops the list. The county is stunningly scenic; it also has one of the lowest life expectancy rates in the region.

Norris was relatively active. She also enjoyed sodas, sweets and frozen dinners. Meanwhile, diabetes runs in her family. So, when her diabetes diagnosis came down, her doctor prescribed insulin shots and told her to watch what she ate.

“You’re sitting there thinking, ‘Well, what does that mean?’ ” Norris says.

Type 2 diabetes can be reversed with weight loss and exercise; but research shows that people need lots of help to achieve control of blood sugar with just a change in diet and lifestyle, and they rarely get enough support. It’s easier for doctors and patients to rely primarily on medication.

Norris says trying to overhaul her diet by herself was confusing and difficult. And when things didn’t change, the doctor just kept increasing her dosage of insulin.

But then Norris lost her health insurance. The injectable insulin cost her hundreds of dollars a month — money she simply didn’t have.

Fortunately, that’s when a couple of nurses who were members of her community stepped in to help — not with cash, but with crucial support of a different sort.

At the nonprofit Beersheba Springs Medical Clinic, a nonprofit clinic founded in 2010 to bring free or low-cost health care to the area, Norris was introduced to an alternative approach to taming her Type 2 diabetes — and the prospect of reversing her diagnosis altogether.

Retired nurses on a mission

In a former parsonage near the clinic, Karen Wickham ladles out lentil stew as a handful of participants in the evening’s health education session arrive.

She and her husband, Steve, are white-haired, semiretired nurses who have dedicated their lives to what they call “diabetes reversal.” They offer six-week seminars to Type 2 patients like Norris, who has also brought along her father and daughter.

“It’s our purpose,” Karen says. “Our purpose in life is to try to help make a difference — first in our community.”

With slide presentations, the Wickhams explain the difference between sucrose and glucose and the science behind the fact that foods like potatoes spike blood sugar, while sweet potatoes don’t. They preach eating as much fiber as a stomach can stand and dropping almost every kind of sweetened beverage.

Steve and Karen Wickham explain course materials to participants in their seminar on Type 2 diabetes in Grundy County, Tenn. The six-week seminar offers detailed instruction on the biology of diabetes, diet and exercise — and provides plenty of individualized support.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

Then they demonstrate ways to burn all those calories. On one evening, Steve invents the “Beersheba Boogie” on the spot, asking participants to raise their knees and pump their fists in place.

All these people will have to find a way to get active at home, because there’s no gym anywhere close. There’s not a proper grocery store nearby either, so healthy cooking can become a real chore. These communitywide obstacles reveal why it can be a struggle for people to maintain their health in rural America. But the Wickhams are working to overcome those barriers.

Steve calls out for applause as participants share their latest health stats — “Her blood sugar is going down! Give her a hand.”

If it sounds like a revival meeting, it kind of is. Steve and Karen Wickham feel compelled to do this work as part of their Christian faith as Seventh-day Adventists — members of a denomination known for a focus on health.

“I think God holds us responsible for living in the middle of this people and doing nothing,” Steve says.

The Wickhams originally moved to Grundy County to take care of ailing parents, and they ended up building their dream home there. They planted vast orchards, vegetable gardens and berry patches to help satisfy their vegetarian diet — a diet common among Seventh-day Adventists.

But once settled in their mountain retreat, the Wickhams grew disturbed by Grundy County’s national health ranking: The county of 13,000 people ranks as the least healthy in Tennessee, by one annual measure. Grundy County has the shortest life expectancy in the state and an elevated rate of diabetes (16 percent of adults), which can eventually result in blindness, kidney failure and amputations.

“I had taken care of diabetic patients for so long, and I knew the progression,” Karen says. “If you truly want the people to get better, you have to treat it with lifestyle interventions.”

Overhauling one’s diet and activity level is the obvious answer, but those changes are hard to start and even harder to maintain.

“Nobody, actually, will make all of the lifestyle changes that we recommend,” Steve says. “But if you’re making the kind of choices that lead you to a healthier lifestyle, then you get better.”

A more hopeful message

Along with their lifestyle counseling, the Wickhams always give a disclaimer, advising people to consult with their doctors about their condition and its treatment. They also acknowledge that their seminars are not yet “evidence based” or backed by peer-reviewed scientific literature. It’s one of the reasons they haven’t been able to get government grants to fund their program directly.

But there are studies showing that people with blood sugar levels in the “prediabetes” range can get back to normal blood sugar by losing 5% of their body weight.

And weight loss and exercise have already been shown to lower hemoglobin A1c levels, which physicians use to monitor a patient’s blood sugar over two to three months.

In addition, new research from Dr. Roy Taylor of Newcastle University in the United Kingdom shows promise for true remission.

“There just hasn’t been the information about the possibility of reversing diabetes,” Taylor says.

Most studies do show Type 2 diabetes, in most patients, marching in pretty much one direction. But Taylor says those studies also involve people who continue to gain weight, which is typical among diabetics.

“Doctors tell their patients, ‘You’ve got a lifelong condition. We know it’s going to steadily get worse.’ Then they turn around, and their patients aren’t losing weight or doing exercise, but they’ve given them this utterly depressing message,” he says.

Taylor’s research finds that if a patient loses 30 pounds or so, diabetes can be reversed in its early stages. Taylor prescribes a strict liquid diet and limited exercise — at first — so as not to stimulate the appetite. People with Type 2 diabetes need to lose fat from the liver and pancreas.

Ultimately, Taylor hopes better nutrition will become the preferred response to high blood sugar in the next decade.

“I think the main headwinds [against progress] are just conceptual ones — of scientists and doctors believing this is an irreversible condition because of what we’ve seen,” he says.

Even the American Diabetes Association has been changing its views. The advocacy group has a new position on Type 2 reversal: “If a patient wishes to aim for remission of type 2 diabetes, particularly within 6 years of diagnosis, evidence-based weight management programs are often successful.”

John Buse, chief of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina medical school, helped write the American Diabetes Association’s revised guidance. “We’ve known, literally since the 17th century, that diet is the key to managing diabetes,” he says.

But it’s hard to write a prescription for lifestyle change.

“Doctors don’t have the time to do it well, so we have often used the sort of short shrift,” he says. ” ‘Eat less carbohydrates and walk every day.’ That has basically no impact.”

The Wickhams are doing their part to add to the scientific data, tracking the blood sugar of the participants in their program. And even the anecdotal, short-term evidence they’ve gathered so far is resonating far beyond Grundy County, and they’ve been traveling more and more lately.

Steve Wickham, who is a nurse, draws blood at the midpoint of his and his wife Karen’s six-week diabetes seminar. The hemoglobin A1c levels measured by the lab test help patients monitor whether the diet and exercise changes they’re engaged in are making a difference in their blood sugar levels.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

The couple just sold their retirement home so they can say yes to all the invitations they’ve received, mostly through Seventh-day Adventist groups, to present their program to other communities around the United States.

Meanwhile, Wendy Norris says the prospect of turning back Type 2 diabetes already has changed her entire outlook on health.

“I felt like I was stuck having to take three or four shots a day the rest of my life,” she says. “I’ve got it down to one already.”

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with Nashville Public Radio and Kaiser Health News.

First Came Kidney Failure, Then There Was The $540,842 Bill For Dialysis

Sovereign Valentine and his wife, Jessica, wait as a dialysis machine filters his blood. Before finding a dialysis clinic in their insurance network, the Valentines were charged more than a half-million dollars for 14 weeks of treatment.

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

For months, Sovereign Valentine had been feeling progressively run-down. The 50-year-old personal trainer, who goes by “Sov,” tried changing his workout and diet to no avail.

Finally, one Sunday, he drove himself to the hospital in the small town of Plains, Mont., where his wife, Jessica, happened to be the physician on call. “I couldn’t stop throwing up. I was just toxic.”

It turned out he was in kidney failure and needed dialysis immediately.

“I was in shock, but I was so weak that I couldn’t even worry,” he said. “I just turned it over to God.”

He was admitted to a nearby hospital that was equipped to stabilize his condition and to get his first dialysis session. A social worker there arranged for him to follow up with outpatient dialysis, three times a week. She told them Sov had two options, both about 70 miles from his home. They chose a Fresenius Kidney Care clinic in Missoula.

Share Your Story And Bill With Us

If you’ve had a medical-billing experience that you think we should investigate, you can share the bill and describe what happened here.

A few days after the treatments began, an insurance case manager called the Valentines warning them that since Fresenius was out-of-network, they could be required to pay whatever the insurer didn’t cover. The manager added that there were no in-network dialysis clinics in the state, according to Jessica’s handwritten notes from the conversation.

Jessica repeatedly asked both the dialysis clinic staff and the insurer how much they could expect to be charged, but couldn’t get an answer.

Then the bills came.

Patient: Sovereign Valentine, 50, a personal trainer in Plains, Mont. He is insured by Allegiance, through his wife’s work as a doctor in a rural hospital.

Total bill: $540,841.90 for 14 weeks of dialysis care at an out-of-network Fresenius clinic. Valentine’s insurer paid $16,241.72. The clinic billed Valentine for the unpaid balance of $524,600.17.

Service provider: Fresenius Medical Care, one of two companies (along with rival DaVita) that control about 70% of the U.S. dialysis market.

Medical treatment: Hemodialysis at an outpatient Fresenius clinic, three days a week for 14 weeks.

What gives: As the dominant providers of dialysis care in the U.S., Fresenius and DaVita together form what health economists call a “duopoly.” They can demand extraordinary prices for the lifesaving treatment they dispense — especially when they are not in a patient’s network. A 1973 law allows all patients with end-stage renal disease like Sov to join Medicare, even if they’re younger than 65 — but only after a 90-day waiting period. During that time, patients are extremely vulnerable, medically and financially.

“To me, it’s so outrageous that I just have to laugh,” said Sov Valentine about the huge bill for dialysis treatments he received.

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tommy Martino/Kaiser Health News

Fresenius billed the Valentines $524,600.17 — an amount that is more than the typical cost of a kidney transplant. It’s also nearly twice Jessica’s medical school debt. Fresenius charged the Valentines $13,867.74 per dialysis session, or about 59 times the $235 Medicare pays for a dialysis session.

When Jessica opened the first bill, she cried. “It was far worse than what I had imagined would be the worst-case scenario,” she said.

Sov had a different reaction: “To me, it’s so outrageous that I just have to laugh.”

Dialysis centers justify high charges to commercially insured patients because they say they make little or no money on the rates paid for their Medicare patients, who — under the 1973 rule — make up the bulk of their clientele. But nearly $14,000 per session is extraordinary. Commercial payers usually pay about four times the Medicare rate, according to a recent study.

Dialysis companies are quite profitable. Fresenius reported more than $2 billion in profits in 2018, with the vast majority of its revenue coming from North America.

The discrepancy in payments between Medicare and commercial payers gives dialysis centers an incentive to treat as many privately insured patients as possible and to charge as much as they can before dialysis patients enroll in Medicare. It may also give dialysis centers an incentive to charge the few out-of-network patients they see outlandish prices.

“The dialysis companies may think they can get closer to what they want from the health plans by staying out-of-network and charging these prices that are totally untethered to their actual costs,” said Sabrina Corlette, a professor at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute. “They have the health plans over a barrel.”

One potential way to save costs on dialysis is to switch to a type that can be done at home, which involves infusing fluid into the abdomen. Called peritoneal dialysis, it is common in Europe but relatively rare in the U.S. In an executive order this month, President Trump announced new incentives to increase uptake of those options.

Brad Puffer, a spokesman for Fresenius Medical Care North America, said the company would not comment on any specific patient’s situation.

“This is one example of the challenges that can arise from a complex healthcare system in which insurers are increasingly shifting the financial burden to patients,” Puffer said in a written statement. “The insurance company should accurately advise patients of in- and out-of-network providers. It is the patient’s choice when they receive that information as to which provider they select.”

Resolution: As a physician, Jessica Valentine is savvy about navigating the insurance system. She knew it was important to find an in-network provider of dialysis. She and the insurance company case manager both searched on the insurer’s online provider directory, she said, and were unable to find one. She even wrote to the Montana insurance commissioner to inquire if the lack of a dialysis provider violated a requirement that insurers maintain an “adequate network” of providers.

With help from the state insurance commissioner, she learned that there was, in fact, an in-network dialysis clinic run by a nonprofit organization that had not turned up in her insurer’s online search or the directory. She immediately arranged for Sov to start getting further dialysis there. But the bills with Fresenius, meanwhile, were adding up.

After a reporter made inquiries, a financial counselor at Fresenius told Jessica that the Valentines qualified for a discount of 50%, based on their income. That would still leave them a bill of $262,400.08.

“It’s still a completely outrageous charge,” Jessica said. “I want to pay what we owe and what’s reasonable and what his care actually cost.”

Unwilling to pay Fresenius more, Allegiance said Jessica should have found the in-network facility earlier. “There is always the potential for customers to misunderstand information about how their health plan works, especially in stressful situations,” a spokesperson for Allegiance wrote.

Jessica is considering contacting a lawyer. If all else fails, the Valentines will consider filing for bankruptcy. A family doctor who works at a rural hospital, Jessica now understands why some of her patients avoid testing and treatment for fear of the cost. “It’s very, very frustrating to be a patient, and it’s very disempowering to feel like you can’t make an informed choice because you can’t get the information you need.”

The takeaway: Dialysis is a necessary, lifesaving treatment. It is not optional — no matter a patient’s financial situation.

Insurers are obligated to have adequate networks for all covered medical services in their plans, though “adequacy” is poorly defined.

So, if it looks like there isn’t an in-network option within a reasonable distance — for dialysis or more basic services from orthopedists or dermatologists — keep digging. Keep in mind that dialysis clinics may be listed as “facilities” rather than “providers” in your directory.

If none are available, seek help from your state’s insurance commissioner. Report your experiences — that’s one way the commissioner can learn that the names listed in the directory aren’t taking patients or are 50 miles away, for example.

If you have insurance through an employer, you can contact your benefits department to go to bat for you. If there is no in-network option, you should get a dispensation to go out-of-network at in-network rates and with in-network copayments.

If you receive a bill for out-of-network care, don’t merely write the check. Ask for an itemized bill and review the charges. You can also ask your insurance company to negotiate with the provider on your behalf. See if the bill counts as a “surprise bill” under your state’s law, in which case you could be “held harmless” from excessive charges.

And when all else fails, try to negotiate directly with the provider. They might have a financial assistance policy, or be willing to lower the cost significantly to avoid turning you over to a debt collector that would pay them pennies on the dollar.

NPR produced and edited the interview with Kaiser Health News’ Elisabeth Rosenthal for broadcast. Nick Mott of Montana Public Radio provided audio reporting.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it here.

What’s Happening With New Abortion Regulations Under Title X

Clare Coleman, CEO of the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association, talks with NPR’s Sarah McCammon about recent changes to Title X regulations.