Examining Biden’s Health Care Pitch

New York Times health reporter Sarah Kliff tells NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro about Joe Biden’s health care plan and how it differs from “Medicare for All.”

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

We’re going to talk policy now – health care policy. That’s because there’s another prescription for the American health care system in the mix among the Democratic presidential field. And it doesn’t call for as sweeping a change as other plans do.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

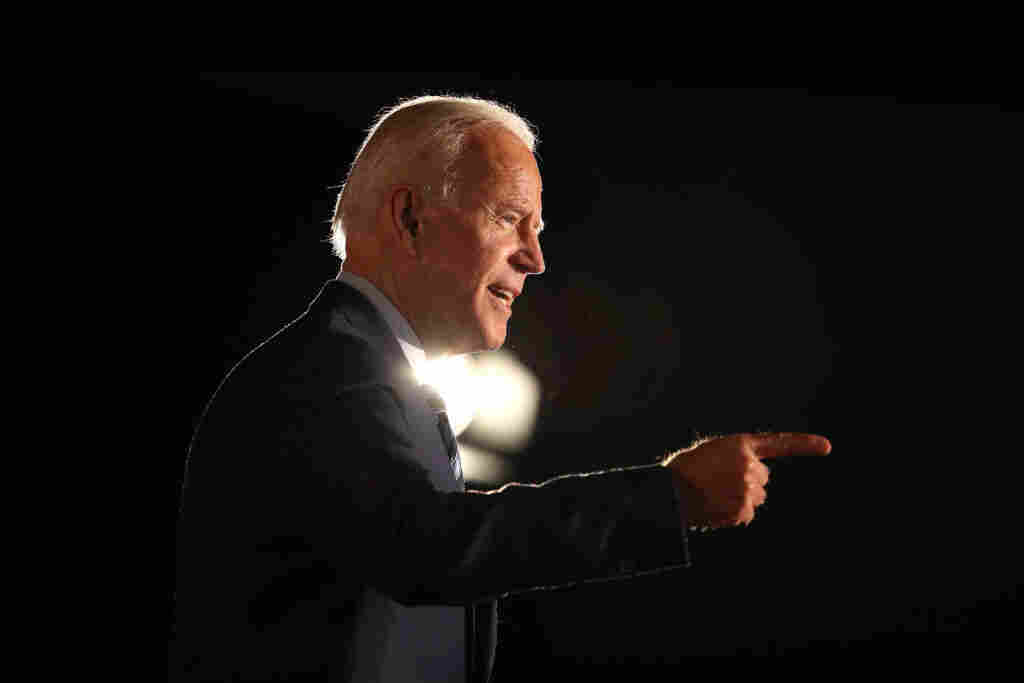

JOE BIDEN: I understand the appeal of “Medicare for All.” But folks supporting it should be clear that it means getting rid of Obamacare. And I’m not for that.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That’s former Vice President Joe Biden announcing his plan on Monday. Let’s take a look at his idea and other plans not calling for expanding Medicare to cover everyone with Sarah Kliff. She covers health care for The New York Times. And she joins us now. Good morning.

SARAH KLIFF: Good morning.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Biden’s pitch is for Obamacare plus. What does that mean?

KLIFF: Yeah. This is a really key divide you’re seeing shape up in the Democratic field. What Biden and a number of other candidates are suggesting is something called the public option, keeping the private insurance that we have now but adding in a government-run option that is going to compete against the profit-motivated plans. And if things go as you think in theory, it will have lower premiums. People will sign up for it. And that should encourage other health care plans to lower their premiums, as well, essentially creating more competition in the private-insurance market.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Where does this fit on the spectrum of plans you’re seeing from the Democrats? I imagine you put Bernie Sanders on one end because he wants a single-payer system that eliminates private health insurance in favor of the government covering everyone. Does this put Biden squarely in the middle?

KLIFF: It’s almost to the right of the spectrum at this point, which is a really wild thing to think about, about how the public option used to be a pretty far-left position, that this is where the liberals in Congress would land. Now the left is really focused on Medicare for All, like Senator Sanders says, eliminating private health insurance, moving everyone to a government plan. The more moderate position has become, let’s build on Obamacare. Let’s add in this public option. So I almost see this as the benchmark that’s being suggested in the Democratic primary. And you wouldn’t have seen that even five, 10 years ago.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Speaking as someone who’s been reporting on health care in the U.S. for a long time now, what are the obvious advantages and disadvantages in a plan like Biden’s?

KLIFF: So I think one of the obvious advantages is that it’s a lot less of a transition, that it would be a huge, huge undertaking to move all of us onto a government health care plan and do it in four years, which is what Senator Sanders’ plan envisions, whereas the Biden plan would not be quite as disruptive. It can advertise choice. You could decide if you want private insurance, if you want the new public plan. But, you know, the things that are the advantage are the exact same things that are the disadvantage. It will not disrupt as many of the things that people don’t like about their health insurance. It won’t, for example, regulate all the health care prices in the United States, which is something the Sanders plan would do. It would probably eliminate a lot of the big surprise bills that I see a lot of my readers sending me. So the fact that it’s less disruptive – that has its advantages – also has its disadvantages, as well.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: So where is the public on this now?

KLIFF: Yeah. So they are warming up to Medicare for All, is what I would say. If you look at the trajectory of polling over the past 20 years, it’s not like there’s some groundswell of support for Medicare for All. Instead, you see a slow, steady, incremental increase in those who think it’d be a good idea for the government to provide health insurance to everybody. But what I find most interesting about the Medicare for All polling is that people really change their minds when they hear different things about it. When people learn Medicare for All would get rid of the insurance they have at work, they get much more negative. When they hear it would get rid of deductibles, they get a lot more positive. So I don’t think the country’s really made up their mind at this point. And that’s why you see this fight in the Democratic Party – is because people are trying to sell their pitch for what would be best for our health care system.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: In the 2018 election, health care became a really strong issue for the Democrats. On the other side of the aisle, what are the Republicans offering? What can President Trump bring to the table?

KLIFF: So President Trump – he does like to talk a lot about having a great, new health care plan. But we haven’t really seen the Republican Party unify around their vision of health care. We spent most of 2017 watching them try and repeal and replace Obamacare. And they were unable to come up with a plan that their caucus agreed on that could pass through Congress. Right now, Republicans are pursuing this lawsuit in Texas that would overturn the Affordable Care Act. And you’ll see Democrats talking a lot about that lawsuit – the Trump administration supporting Obamacare repeal in that particular legal battle. So, you know, you have President Trump discussing a lot of big promises for a good health care plan. You also have the Department of Justice supporting a lawsuit that would end protections for pre-existing conditions. And that’s something I think you’re going to see come up a lot as we get into the election cycle.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That’s Sarah Kliff of The New York Times, speaking via Skype. Thanks so much.

KLIFF: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.