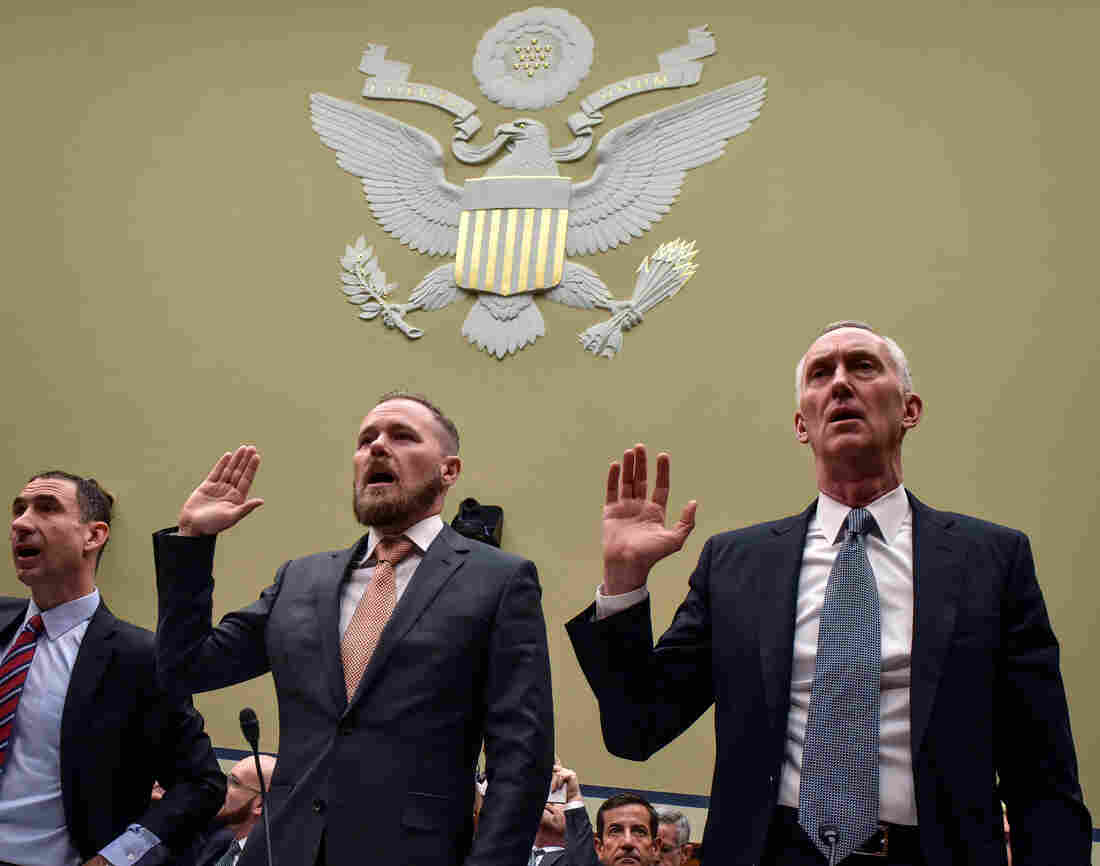

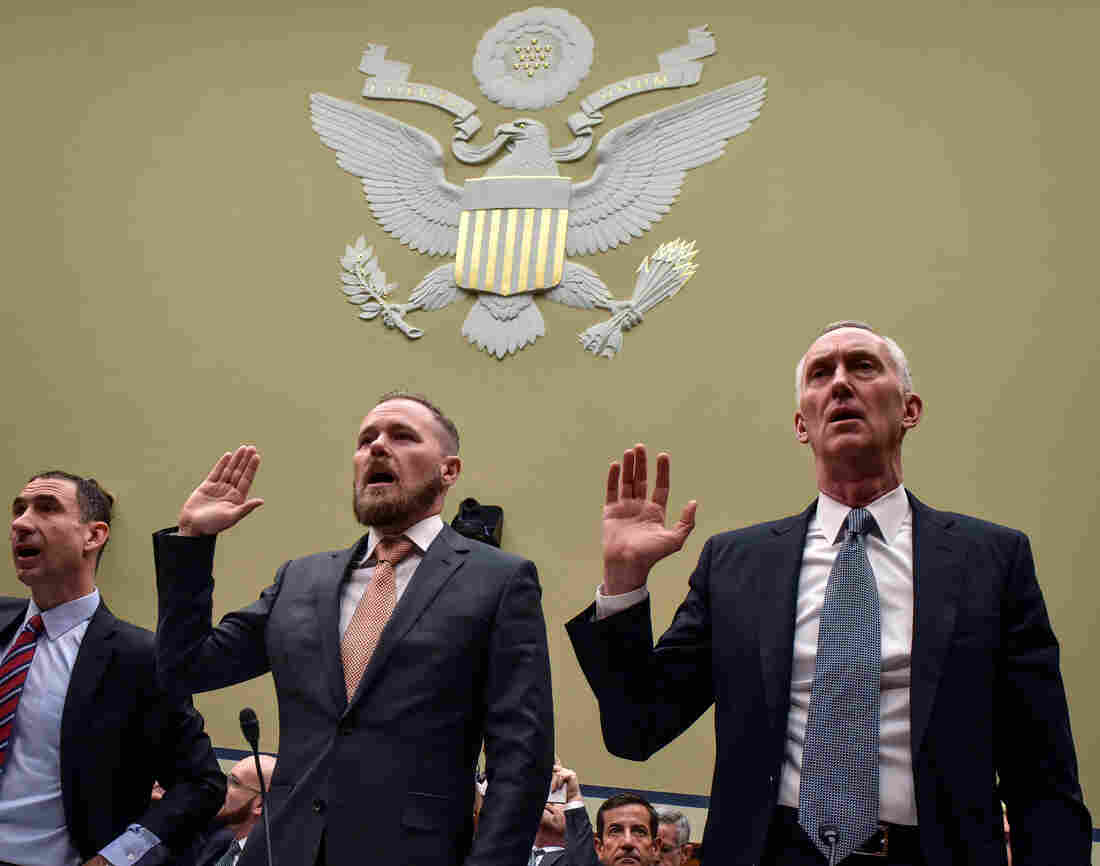

During testimony before a congressional hearing on drug prices this month, Dr. Aaron Lord (left), a patient advocate and AIDS activist, publicly challenged Daniel O’Day, CEO of Gilead Sciences (right), to lower the price of Gilead’s HIV prevention drug Truvada.

Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post/Getty Images

When the first HIV drug, AZT, came to market in 1987, it cost $10,000 a year.

That price makes Peter Staley laugh today. “It sounds quaint and cheap now, but $10,000 a year at that time was the highest price ever set for any drug in history,” he says.

At the time, the price Burroughs Wellcome set for the drug sparked outrage. The AIDS epidemic was an urgent national crisis. For many, the diagnosis was a death sentence. The TV-viewing public was horrified by endless images of young men, suddenly sick and dying. A lost generation.

ACT UP — the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power — was established by Staley and others to drive government attention and research toward a cure. A key early goal of the movement: force down the price of AZT. Whatever it took.

Demonstrators from the organization ACT UP, angry with the federal government’s response to the AIDS crisis, protest in front of the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration in Rockville, Md., on Oct. 11, 1988, and effectively shut it down. By mid-morning some 50 of the protesters were arrested.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

“I led an action where we invaded [Burroughs Wellcome] headquarters in April of 1989 and sealed ourselves into a third floor office and caused $9,000 of property damage,” Staley says. “In September, we infiltrated the New York Stock Exchange before the opening bell with fake IDs and got into a VIP balcony and unfurled a banner that said ‘Sell Wellcome,’ and set off Marine fog horns that drowned out the opening bell. And we threw out fake $100 bills to the traders below us.”

He can’t quite remember, but thinks the fake bills read, “F*** your profiteering, we die while you play business.”

“The company lowered the price another 20% three days after that,” Staley says.

Because of ACT UP’s effectiveness, he says, the price of AZT went from $10,000 a year to $3,200 a year. “We were a major news story back then,” he says. “And that was essential to all of the victories that we had.”

Now, AIDS activists — drawn from that older generation, and from a new one — are working again to bring down the prices of HIV medication. This time, the drugmaker is Gilead Sciences, and the drug is Truvada. It’s the only FDA-approved version of PrEP, which stands for pre-exposure prophylaxis, currently available commercially in the U.S.

The list price? $1,780 a month, or $21,360 per year — more than 350 times the cost of generic versions of the drug available in most other countries.

“There are remarkable parallels to what’s happening with Gilead these days,” Staley says. “We are back to the Burroughs Wellcome days, where we have one company — we have a monopoly dominating the market and raking in money for what are actually government inventions. And we’re having massive access issues because of it.”

Still, the issue is playing out in a different era, Staley notes, and that’s requiring new tactics from advocates for patients.

“AIDS is an old story now,” he says. “That’s our new reality. So we accept it and we work around it.”

Today, though the HIV epidemic is quieter, it’s still deadly. People can live long lives with the virus, but there’s no cure, and it continues to spread. Gay and bisexual men, African Americans, Latinos and people living in the South are especially at risk.

Staley is now part of PrEP4All — an offshoot of ACT UP. The group was launched last summer, but is ramping up its activity now in light of the Trump administration’s plan to end the spread of HIV in America by 2030. That goal can only be reached if more people get on the PrEP regimen — currently only a fraction of the 1.1 million people at significant risk for getting HIV are taking the daily prevention pill.

To meet this new moment, Staley says, PrEP4All activists are using some of the same broad tactics as ACT UP, but also increasing their activity behind the scenes. They’re showing up in front page articles and editorials, at pharmaceutical shareholders meetings and publicly confronting officials in the Trump administration. They have a petition and a hashtag and a white paper — and have harnessed the tools of social media to help hold elected officials accountable.

“We have a congressional strategy, and we have what ACT UP never had — a legal strategy,” Staley says. “We’re working with deep-pocketed law firms, which is totally something that ACT UP never thought to do.”

He credits the young activists who are part of today’s movement for that new approach. “The sophistication by the millennial activists that I’m working with today has my head spinning,” Staley says. “They’ve got this historical template that says, ‘Anybody can do this. You just have to have the willpower and the self-confidence.’ They’re absolutely on fire — they already are making changes and they will continue to.”

Jake Powell, who works in New York City, is originally from Wyoming. Powell joined the PrEP4All movement after having to go off the drug for six months because it was too costly, even for someone with health insurance.

Courtesy of Brandon Cuicchi

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Brandon Cuicchi

The public “disruptions” PrEP4All has engaged in recently — along the lines of those ACT UP was known for — generally fall into two categories: shaming Gilead into voluntarily lowering the price of Truvada, and pressuring the government into challenging Gilead’s patent of the medication, so generic competition might force the price down.

“Our goal is to get Gilead Sciences to release the patent,” says Emily Sanderson, a co-founder of PrEP4All and one of the millennial activists Staley mentioned. “Gilead has the power to make PrEP available right now for everybody and they’re not doing it,” Sanderson says.

In mid-May at a congressional hearing focused on the price of Truvada, PrEP4All activist Dr. Aaron Lord made a personal appeal to Gilead CEO Daniel O’Day in front of lawmakers.

“Mr. O’Day, why not lower the price of Truvada to $15 a month, right here, today, at this hearing?” Lord asked. “We look to you today to ensure that every single person in this country can protect themselves from this plague.”

O’Day did not respond to that appeal. Instead, throughout the hearing, he explained the company’s rationale.

“The pricing set in the United States takes into account the innovation it brings, the cost of the health care of treating an HIV patient, [and] the ability to invest back in research and development,” O’Day said. He also said the company was working to “make sure our access programs are effective” so that price was not a barrier for patients.

From Gilead’s perspective, Truvada is under patent for a limited time and shareholders want to see profits. Gilead also argues the price isn’t the problem — lack of awareness, stigma and homophobia are the problems.

Gilead also points out that relatively few patients have to pay the list price. The company provides the drug at a discount to government programs; it just donated some 2.4 million bottles of Truvada a year to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to cover some uninsured patients; and it has a copay assistance program for people with high deductibles.

PrEP4All activists are generally dismissive of these efforts.

In a Manhattan demonstration this spring, members of ACT UP protest drug company lobbying of elected officials. The AIDS activists see Truvada’s high price as another example of profiteering by some makers of prescription drugs.

Courtesy of Brandon Cuicchi

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Brandon Cuicchi

“They’ll highlight their access programs. They’ll highlight the ways that some folks are covered. But there are so many gaps,” says activist Jake Powell, who takes PrEP. “And I personally fell through one of those gaps.” The gap occurred when Powell’s high-deductible insurance plan, which had accepted Gilead’s copay assistance for one year, stopped counting the payments towards the deductible the second year.

“I was off [PrEP] for about six months because I couldn’t afford it,” Powell says.

The activists are also focused on the government’s role in allowing the price of Truvada to stay high. “The CDC can come in and reduce the cost of PrEP and provide it at an affordable price,” Sanderson argues.

PrEP4All makes two points on this front. The first, detailed in a recent investigation by The Washington Post, is that the CDC has its own valid patents for PrEP that the agency could be enforcing (something Gilead disputes) and that taxpayer money was used in the studies underlying Gilead’s Truvada patent. Secondly, the activists argue, the government has the power under the Bayh-Doyle Act of 1980 to “march in” and break Gilead’s patent in the name of public health, so that competition from generics could bring the price down.

So far, neither the CDC nor Gilead have shown signs, at least publicly, of being moved by PrEP4All’s arguments. I ask Peter Staley if that lack of response from Gilead and the CDC is discouraging.

“The patent issue is very much bubbling at a boil right under the surface,” Staley says. “It’s not visible to the public, but it is a raging issue. And there are Democrats on both the House side and the Senate that want answers and are not going to let this go.”

He pauses, then adds: “We won’t let them let it go.”

Let’s block ads! (Why?)