Want New Taxes To Pay For Health Care? Lessons From The Affordable Care Act

A demonstrator celebrated outside the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015 after the court voted to uphold key tax subsidies that are part of the Affordable Care Act. But federal taxes and other measures designed to pay for the health care the ACA provides have not fared as well.

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images

It was a moment of genuine bipartisanship at the House Ways and Means Committee in October, as Democratic and Republican sponsors alike praised a bill called the “Restoring Access to Medication Act of 2019.”

The bill, approved by the panel on a voice vote, would allow consumers to use their tax-free flexible spending accounts or health savings accounts to pay for over-the-counter medications and women’s menstrual products.

Assuming the measure ultimately finds its way into law, it would also represent the latest piece of the Affordable Care Act’s financing to be undone.

Over-the-counter medication had been eligible to be considered a pretax expenditure in this way, before the ACA. But that eligibility was eliminated as part of a long list of new taxes and other measures that were designed to generate revenue to help pay for expanding health coverage to more people — a roughly $1 trillion cost of the health law over its first 10 years.

“It is paid for. It is fiscally responsible,” said President Barack Obama as he signed the ACA into law in 2010.

But not so much anymore. Many of the taxes and other provisions aimed at paying for that expanded health coverage “have been eliminated, delayed or are in jeopardy,” says Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan budget watchdog group. “All this stuff, it turns out, is very unpopular.”

The first piece of financing to disappear happened before most of the law even took effect. In 2011, Congress repealed a requirement that small businesses report to the IRS any payment of more than $600 to a vendor. The idea was that if more such payments were reported to taxing authorities, more taxes due on that income would actually get paid.

But small businesses complained — loudly — that the new paperwork requirement would be excessive, and Congress (and Obama) eventually agreed. The change alone eliminated an estimated $17 billion in ACA financing over 10 years.

Next, in 2015, Congress delayed (for the first time) the “Cadillac tax,” a 40% tax on the most generous employer health plans; one goal of that tax had been to curb excessive use of medical services.

That congressional delay came after intense lobbying by a coalition of business, labor and patient advocacy groups that banded together in a group called the Alliance to Fight the 40. It first got Congress to delay the Cadillac tax’s implementation from 2018 to 2020, then further pushed that date to 2022. And this past summer the House voted overwhelmingly to altogether eliminate the tax, which had been estimated to raise nearly $200 billion over the next decade.

Also on ice, thanks to that 2018 bill, are levies that were supposed to be paid by medical-device makers and health insurance companies, originally worth a combined $80 billion in financing during the law’s first decade.

Yet another — albeit fairly small — source of financing for the law went away in the 2017 GOP tax bill, which zeroed out the tax penalty for failing to have health insurance. The penalty raised $4 billion in 2018, the last year it was in effect.

Now it should be pointed out that the two ACA taxes that generate the most revenue are still on the books and collecting money. They are aimed at people with high incomes (more than $200,000 for individuals and $250,000 for couples) and were estimated to bring in more than $200 billion from 2010 to 2019. The measures, which don’t deal directly with services or provisions of the ACA, raise Medicare taxes on people at those higher incomes and increase taxes on unearned income.

The durability of those two taxes does not surprise Goldwein. Some are “unpopular to repeal,” he says, like “a tax on the rich that funds Medicare.”

What Goldwein does find surprising, though, is how durable some of the ACA’s other financing measures — reductions in spending — have been. For example, the health law, somewhat controversially, reduced Medicare payments to hospitals, insurance companies and a broad array of other health providers.

“The Medicare cuts have been for the most part surprisingly sustainable politically,” Goldwein says. Even when the GOP took over the House in 2011, its budget maintained the reductions from the ACA. So did the 2017 GOP “repeal and replace” proposal.

On the other hand, the appointed board of experts that was to rein in future Medicare spending, the “Independent Payment Advisory Board,” never got off the ground. Congress formally repealed it in 2018.

So what does this all mean? The past decade has shown that it has been relatively easy to make hard-won tax increases go away, suggesting that interest groups — particularly health industry groups representing drugmakers, insurers and hospitals — still wield a lot of power on Capitol Hill.

“Right now, everyone wants to cancel a 3% tax on the health insurance industry,” he says, referring to the current efforts of a major ad campaign by a coalition of small-business owners and insurance groups to get Congress to delay or cancel that ACA-linked tax.

Given how much money from health insurers is going into fighting that tax, he says, how likely is it that Congress — even one controlled by Democrats — would really “cancel the whole industry” by passing a “Medicare for All” bill?

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Gene-Edited ‘Supercells’ Make Progress In Fight Against Sickle Cell Disease

As part of a clinical trial to treat sickle cell disease, Victoria Gray (center) has vials of blood drawn by nurses Bonnie Carroll (left) and Kayla Jordan at TriStar Centennial Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Doctors are reporting the first evidence that genetically edited cells could offer a safe way to treat sickle cell disease, a devastating, incurable disorder that afflicts millions of peoplearound the world.

Billions of cells that were genetically modified with the powerful gene-editing technique called CRISPR have started working, as doctors had hoped, inside the body of the first sickle cell patient to receive the experimental treatment, according to highly anticipated data released Tuesday.

The edited cells are producing a crucial protein at levels that have already exceeded what doctors thought would be needed to alleviate the excruciating, life-threatening complications of the genetic blood disorder, the early data show. Moreover, the cells appear to have already started to spare the patient from the agonizing attacks of pain that are the hallmark of the disorder.

“We are very, very excited,” says Dr. Haydar Frangoul of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn., who is treating the patient. “This preliminary data shows for the first time that gene editing has actually helped a patient with sickle cell disease. This is definitely a huge deal.”

Frangoul and other researchers caution, however, that the results involve just one patient who was only recently treated. It is far too soon to answer the most crucial questions: Will the modified-cell treatment continue to improve the patient’s health? Will the treatment keep working? Will it help her live longer? Is it safe in the long term?

“We are hoping it is” a success, Frangoul says. But “it is still too early to celebrate.”

NPR has exclusive access to chronicle the experience of Frangoul’s patient, Victoria Gray of Forest, Miss., the first person with a genetic disease to be treated with CRISPR in the United States.

“So look at this,” Frangoul said recently with a smile, as he showed Gray her latest blood test results. The testing indicated that the genetically modified cells had already started producing the crucial protein at levels doctors hope will alleviate her suffering.

“I am super-excited about your results today,” Frangoul said.

In July, Gray was recovering from the medical procedure, which involved using an experimental technique called CRISPR to edit the genes of her own bone marrow cells.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

While Gray knows it’s still very early, she described how the treatment appears to be helping her. She has not suffered any of the painful attacks that torture sickle cell patients and has not needed to rush to the hospital for care since getting the modified cells this summer. She has not needed any blood transfusions either and has begun to reduce the pain medication she had been taking chronically.

“It’s a miracle,” says Gray, who says she has hope for the first time after a lifetime of struggling with excruciating pain and debilitating, life-threatening complications of the disease. Sickle cell disease is an inherited condition that is marked by defective oxygen-carrying red blood cells.

“When you pray for something for so long, all you can have is hope,” says Gray, 34, who has four children. “It’s amazing.”

The early results of the research were released by the two companies sponsoring the study that Gray volunteered for, Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Boston and CRISPR Therapeutics in Cambridge, Mass.

“This is a very important scientific and medical milestone,” said Dr. Jeffrey Leiden, chairman, president and CEO of Vertex. “We have potentially cured this patient with a single treatment. We are very hopeful.”

While Gray experienced some complications after the treatment, she recovered, and none of the problems is believed to have been caused by the treatment itself, according to the companies.

“I think it’s enormously exciting that we’ve reached a point where gene editing using CRISPR is being applied to sickle cell disease,” says Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health. Collins, who is not involved in the research, noted that sickle cell disease affects about 100,000 people in the United States and millions more worldwide.

“To be able to take this new technology and give those people a chance for a new life, which it really would be, is a dream come true,” Collins says.

Because of the promise of research like this, the National Institutes of Health is launching a $200 million partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to find ways within 10 years to make expensive, complicated gene-based treatments affordable and practical in poor countries, where diseases such as sickle cell are most common. (The Gates Foundation provides support for coverage of global health and development by NPR.)

“The progress that we’ve seen in gene-therapy approaches for sickle cell disease in the U.S., including Victoria Gray and her involvement in this gene-editing protocol, made it clear that it was time to get started on the next phase of this,” Collins said. “If this is starting to work — but wouldn’t work where most of the patients are, which is Africa — we need to get busy and take it to the next level.”

The companies conducting the sickle cell study had previously only disclosed that the first patient in the trial had been treated and that another patient with a related blood disorder, beta thalassemia, had undergone CRISPR treatment this year and had not needed a blood transfusion for four months.

Gray underwent the gene-editing treatment at the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

That’s still true after nine months, according to the new data. The beta thalassemia patient, who was treated in Germany, has not been publicly identified. Typically, beta thalassemia patients need regular transfusions to survive. The CRISPR-treated patient normally needed more than 16 transfusions every year, according to the companies. That patient too experienced health problems after the treatment but also recovered, and none is believed to have been caused by the treatment.

“This is the first evidence that in people the new CRISPR technology has the potential to be curative for serious genetic diseases,” said Dr. David Altshuler, the chief scientific officer at Vertex.

“And this is just the beginning for this new type of therapy. Its applications can go beyond sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia to other genetic diseases.”

Many researchers think CRISPR could revolutionize medicine. The technique enables scientists to make very precise changes in DNA much more easily than ever before.

Doctors are also trying to use CRISPR to treat cancer. Most of that research is happening in China, and almost none of the results have been reported. But the University of Pennsylvania, which has tried CRISPR on three cancer patients, recently reported that gene editing appears feasible and safe. Another study recently started recruiting cancer patients in the U.S. and Australia.

Later this year, doctors in Boston are planning to use CRISPR for the first time to edit cells while they are still inside patients’ bodies — in retinas — in hopes of restoring vision in patients with an inherited form of blindness.

When NPR interviewed Gray most recently, she had just driven five hours back to Nashville after spending about a month at home in Mississippi with her family. She had been in Nashville for about three months over the summer to undergo the procedure on July 2 and then recover from the treatment, which required the equivalent of a bone marrow transplant.

During the return visit, Gray wore a black hooded sweatshirt emblazoned with the word “warrior” across the front.

“You know, they call sickle cell patients warriors, and I saw this shirt at Walmart so I had to get it,” Gray says. “It’s a constant battle.”

Sickle cell disease is a cruel genetic disorder that deforms red blood cells into defective sickle-shaped cells. The cells jam up the bloodstream, damaging vital organs and causing myriad health problems, in addition to the bouts of intense pain. Many patients with the disease can’t work or go to school. Many die before reaching middle age from complications such as heart attacks and strokes.

Researchers caution that Gray’s results are preliminary since they involve just one patient. There is still a lot that is unknown, including whether the treatment will make a lasting improvement in Gray’s health and whether it will be safe in the long term.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

“I had moments where I was just standing, laughing [and] talking with friends, and then the next thing you know, my husband had to carry me into the emergency room because I couldn’t use my legs because they hurt so bad,” says Gray, who has already suffered heart damage from her disease.

“And when you can’t help yourself, it’s just one of those things that just make you want to give up,” she says, her voice cracking with emotion.

Before Gray saw Frangoul, nurses at TriStar Centennial Medical Center took 16 vials of blood from her for tests as part of the clinical trial. The study is designed to eventually involve 45 patients in the United States, Canada and Europe. The beta thalassemia trial is designed to eventually involve 45 patients in Canada, Germany and London.

As the nurses filled one big blood tube after another, Gray described her homecoming a few weeks earlier.

“My oldest son — when he did his double take and realized I was in the car — he took off running, and he just grabbed me and held onto me. And the twins saw me from inside the house. My mama said that my daughter was, ‘My mama’s outside.’ She was just jumping. They knew it was Mama,” she says. “It’s emotional for me, you know, because I love them so much. I did this for them. So, it’s worth it.”

After Gray was done giving her blood sample, she met with Frangoul, who gave her a brief physical exam before showing her a sheet of paper with her latest test results.

“It looks like there are signs that you are starting to make fetal hemoglobin, which is very exciting,” Frangoul said.

Fetal hemoglobin is a protein that is normally produced only by fetuses and newborn babies for a short time after birth. So scientists used CRISPR to edit a gene in bone marrow cells that had been removed from Gray’s body.

The edited cells were infused back into her system, and the editing change allowed the cells to start producing fetal hemoglobin again. The hope is that the fetal hemoglobin will compensate for the genetic defect that has resulted in sickle cell disease and its abnormal form of adult hemoglobin.

The edited cells began functioning about a month after being infused into Gray’s body. Four months after Gray received the cells, her blood tests show that 46.6% of the hemoglobin in her system is fetal hemoglobin, according to the companies. That far exceeds the 20% to 30% that doctors thought would be needed to help her. And her fetal hemoglobin levels are still rising, Frangoul said in an interview. In addition, 94.7% of Gray’s red blood cells contain fetal hemoglobin, the companies reported.

Gray suffered a blood infection, gallstones and abdominal pain after the grueling procedure, which involved the equivalent of a bone marrow transplant. The beta thalassemia patient developed pneumonia and a liver problem. But none of those complications is believed to have been caused by the edited cells, the companies said.

Other researchers are testing another approach for sickle cell that involves using a virus to insert a healthy gene into sickle cell patients’ cells. That approach is also showing promise. Scientists are also planning to try to use CRISPR to correct the defective gene itself, which would be more difficult.

Frangoul stresses that it’s too soon to know if the fetal hemoglobin production will continue and how it might help Gray’s health over a longer period of time.

“I just want to make sure this is something we watch very carefully every visit and see how things are going,” he told Gray.

But Frangoul, medical director of pediatric hematology/oncology at HCA Healthcare’s TriStar Centennial Medical Center, knows Gray has been feeling better.

“You haven’t been in the hospital since I last saw you, correct?” he said. “No emergency rooms, no hospitals. How about that? That’s good. Excellent. Perfect. This is extremely encouraging.”

While Frangoul says some sickle cell patients can go for extended periods without severe attacks of pain, Gray says that normally she would have suffered some kind of episode in the period since she received the edited cells. In the two years before the treatment, Gray had experienced seven sickle cell crises a year.

At a recent checkup, Dr. Haydar Frangoul gave Gray preliminary results showing that her body is making fetal hemoglobin, a protein that could alleviate the symptoms of her sickle cell disease.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

“It’s special, especially coming up on the holidays, because sometimes I would be in the hospital on Christmas. And so I’m looking forward to a whole new life for all of us,” she said.

Gray calls edited cells her “supercells.”

“They seem to be super after all,” Gray said, laughing.

Frangoul plans to follow Gray for many more months to see if her “supercells” are really making her healthier, and for even longer to see if they help her live longer. Researchers plan to check up on Gray and other study subjects for 15 years to make sure the cells are not causing any long-term side effects of their own.

“This would be life-changing, not only for Victoria but for many sickle cell patients,” Frangoul said. “If this is determined to be safe and effective, I think it can be transformative for patients with sickle cell disease.”

Before the treatment, Gray was so weak from her disease that she couldn’t work or go to school and hadn’t been able to participate in many of her children’s activities.

Since the treatment, she felt strong enough to go to one of her son’s football games for the first time. She hopes that maybe now she’ll be able to spend a lot more time with her kids and see them grow up.

“I don’t really want anything extravagant,” Gray said. “I just want a simple life with my family and the people who I love and people that love me, and just live, you know? This could be the beginning of something special.”

Open Enrollment For 2020 Obamacare Has Begun

This year the federal health insurance marketplace Healthcare.gov has a few new bells and whistles. (This piece initially aired on Nov. 3, 2019 on Weekend Edition Sunday.)

When It Comes To Vaping, Health Officials Insist There’s A Lot At Stake

A former vaper has a warning for others. And, scientists work to understand how nicotine affects the teenage brain. (This segment initially aired on Oct. 10, 2019 on Morning Edition.)

Trump Administration’s Efforts To Ban Most Flavored Vaping Products Have Stalled Out

The White House is apparently backpedaling on its plan to ban most flavors in vaping products. The proposed FDA rule is unpopular with vape shop owners, and that’s creating political blowback.

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

The Trump administration’s efforts to ban most flavored vaping products have stalled out. The president announced two months ago that he would do something to address the youth vaping epidemic. A plan was supposed to have been announced in a matter of weeks. NPR science correspondent Richard Harris explains what happened instead.

RICHARD HARRIS, BYLINE: When President Trump said he was endorsing a Food and Drug Administration proposal to ban most flavored vaping products, he acknowledged there were some economic consequences.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Vaping has become a very big business, as I understand it – like, a giant business in a very short period of time. But we can’t allow people to get sick, and we can’t have our youth be so affected.

HARRIS: The policy proposal hit just as health officials were investigating lung injuries and deaths among people who vaped. Scientists now say that’s primarily from vaping dubious marijuana products. But Paul Billings at the American Lung Association was also focused on the role that flavored e-cigarettes played in teen nicotine addiction.

PAUL BILLINGS: We were very optimistic, encouraged when the president announced that he wanted to clear the markets of all flavored e-cigarettes that play such an important role in addicting millions of kids to these products.

HARRIS: That optimism started to fade after the policy did not appear as promised in the following weeks.

BILLINGS: It stretched into months. A package was sent to the White House for review, and then it cleared. And then everything stopped on November 5.

HARRIS: The Washington Post reports that’s when the president’s political staff advised him not to sign off on the new rules.

Paul Blair at the conservative group Americans for Tax Reform was part of the push against the new rules.

PAUL BLAIR: Look. There are legitimate concerns about teens experimenting with these products, but running towards the 1920s in terms of prohibition is a vote-losing issue.

HARRIS: That message hit the airwaves of Fox News, which ran commercials like this one.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: If you enact a flavor ban, this will cost you the election.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: I vape, and I vote.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: Vapor Technology Association is responsible for the content of this advertising.

HARRIS: And advocates assert that a vaping flavor ban could tilt the election in close states against Trump. Blair’s organization polled people who vape in swing states like Michigan a few years back.

BLAIR: Three out of 4 of these adult consumers are single-issue voters.

HARRIS: And Blair says that issue is access to vaping, including flavored products. Some also argue that getting rid of flavored vaping products could drive people back to smoking cigarettes, which are the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. On top of that, Blair says the industry itself provides 150,000 jobs through vape shops and manufacturers.

BLAIR: It’d be a pretty significant hit in an election year for a guy that’s focused on deregulations, spurring economic growth and not killing jobs.

HARRIS: Big Tobacco is also part of the story, says Paul Billings at the American Lung Association.

BILLINGS: The largest tobacco companies in the world, like Altria and Reynolds, are major players in the e-cigarette business, along with these vape shops.

HARRIS: And these forces appear to have won out over the public health advocates. So Billings says the lead could well shift to states, counties and cities.

BILLINGS: And so we fully expect, irrespective of what the administration does or does not do, that states and localities will continue to move forward.

HARRIS: A White House spokesman says the new rules haven’t been killed, but it’s not clear what, if anything, will survive this process.

Richard Harris, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF SMALL BLACK SONG, “SOPHIE”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

For Supporters Of Abortion Access, Troubling Trends In Texas

Whole Woman’s Health, an abortion provider in Texas, was forced to close its doors in 2014 as a result of House Bill 2 taking effect. Despite the Supreme Court’s overturning the law, most of the shuttered clinics never managed to reopen.

Pu Ying Huang

hide caption

toggle caption

Pu Ying Huang

Over the past few years, abortion providers in Texas have struggled to reopen clinics that had closed because of restrictive state laws.

There were more than 40 clinics providing abortion in Texas on July 12, 2013 — the day lawmakers approved tough new restrictions and rules for clinics.

Even though abortion providers fought those restrictions all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, and managed to get the restrictions overturned in 2016, most of the affected clinics remain closed.

Today, there are just 22 open clinics in a state that is home to 29 million people.

Although abortion providers won the legal battle, they appear to be losing the ground war. Most clinics are clustered in the major cities of Dallas, Houston and Austin, while women who live in smaller cities and towns that once had clinics now have to travel long distances to get an abortion.

The town of San Angelo, for example, once had a Planned Parenthood clinic, but it had to close in 2013. It had been one of the last abortion providers in West Texas, a sprawling, dry and mostly rural region where most residents must drive at least three hours to reach a major city.

Susanne Fernandez, who worked at the San Angelo clinic for almost 30 years, gets emotional talking about its closure. “I loved working for Planned Parenthood.”

Fernandez blames the closure on the 2013 state law, known as House Bill 2, which required abortion clinics to have the same sort of equipment, standards and staffing as surgical centers — and also required the doctors performing abortions to obtain admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. She says complying with those rules would have been extremely difficult and expensive. Still, the decision to close the San Angelo clinic was tough.

“The last day was sad. It was somber,” Fernandez says. “We did a lot of cleaning up. We all knew that was it.”

Abortion providers in Texas eventually sued the state. But as the legal challenge worked its way through the courts, many of the clinics were forced to stop providing services.

At one point, Texas had only 17 clinics, says Kari White, an investigator with the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas, Austin. She says women living in rural Texas were affected the most.

“What we saw is that [in] West Texas and South Texas, access was incredibly limited,” White says, “and women living in those parts of the state were more than 100 miles — sometimes 200 or more miles — from the nearest facility.”

White’s research team conducted surveys and interviews with women who were seeking abortions as clinics were shutting down. A 19-year-old woman told the researchers she considered giving up because it was so hard to find an open clinic.

“It was a very hard thing to do, like to keep calling and calling and calling,” the woman told researchers. “I almost was like, you know, ‘Well, forget it.’ … But then, because I knew at the end of the day it was something that I had to do, it was like I don’t care how many people I have to call or how far I have to go. I have to do it.”

That woman eventually found a clinic 70 miles away and was able to get the abortion. But in some other cases, women had to carry unwanted pregnancies to term.

Under Texas law, women have to have two appointments with an abortion provider. After an initial appointment at a clinic, the women must wait 24 hours before getting the procedure. That means they often have to make a long trip at least twice, or pay for a hotel nearby. The waiting period is only waived if a woman lives more than 100 miles away from the closest clinic.

One 23-year-old woman from Waco, a married mother of two, told researchers she made appointments to get an abortion at two different clinics. But both appointments were canceled after the clinics were forced to close. She was unable to end the pregnancy.

“I was pretty upset, but I just decided that I guess I’ll have to just ride it out,” she told researchers. “I didn’t know what else to do, who else to call.”

Eventually, in the summer of 2016 — three years after H.B. 2 passed — the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the tough new restrictions on clinics. But most of the clinics never reopened.

“There hasn’t been this rush of clinics reopening following the Supreme Court decision,” White says. “So there are still just clinics concentrated in the major metropolitan areas of Texas.”

The ruling has also been a mixed bag for anti-abortion activists, says John Seago, the legislative director for Texas Right to Life.

“The closures of clinics is definitely a victory for the movement, obviously,” he says. “However, how are we in this situation in the first place is what my organization looks at.”

Seago says anti-abortion activists in Texas are in this situation because of Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court case that made abortion legal in the U.S. He says it’s the reason anti-abortion activists fight legal battles on the state level in an effort to reverse Roe.

Seago says the Supreme Court ruling on Texas’ law was a big blow to the larger goal of slowly dismantling Roe.

Some new options in recent years

Over the past three years, a few abortion providers have decided to open clinics in Texas.

For example, earlier this year Kathy Kleinfeld opened a new abortion clinic in Houston — a city that already has a few clinics providing abortion.

Kleinfeld, a longtime consultant for abortion providers in Texas and other states, decided to open in Houston after carefully looking at the demand for services in that region. Her clinic provides medical abortions using pills, but not surgical abortions.

Kathy Kleinfeld opened Houston Women’s Reproductive Services, which offers medication abortions, because she saw a need for more flexible scheduling.

Gabriel C. Pérez/KUT

hide caption

toggle caption

Gabriel C. Pérez/KUT

“Due to the closure of so many clinics, the remaining clinics that are open are very busy, and they are very strict in the scheduling,” Kleinfeld says. “So our goal was to offer flexibility in scheduling.”

Kleinfeld says her clinic could help take some pressure off the remaining clinics in Houston. She says so far her patients have been professionals, students and women who drive over from Louisiana.

But she emphasizes that getting her clinic up and running was not easy, despite her intimate knowledge of the complex rules and mandatory paperwork and the surprise inspections involved in operating as a licensed abortion provider in the state of Texas.

Kleinfeld predicts that opening, running and keeping a clinic open will always be difficult in Texas.

“There’s always been volatility and conflict and struggles,” she says. “Always. And this is not for the faint of heart.”

Andrea Ferrigno agrees with that assessment. As the corporate vice president of Whole Woman’s Health, Ferrigno helps operate several clinics that offer abortion in Texas.

She recalls that after H.B. 2 passed in 2013, Whole Woman’s Health was forced to close two clinics — one in Austin and another in Beaumont, a small city near the Louisiana border. So far, Whole Woman’s Health has only been able to reopen the Austin clinic.

“It’s basically starting from scratch,” Ferrigno says. “You laid off the staff, you don’t have any physicians that work there anymore. Some of the doctors didn’t even renew their physician licenses.”

Ferrigno says clinics that closed may have lost the required state-issued license needed to operate in Texas. Applying for a new one is a significant bureaucratic hurdle. Some clinics might have lost their leases, been forced to vacate their buildings, and sell off equipment.

“There are a lot of different limitations,” she says. “There’s also the question of — or the fear of — security challenges. People picketing the clinic, picketing their homes. There’s a lot that goes into that.”

But the cost of not reopening — particularly in a community that had only one clinic to begin with — may be high.

Take San Angelo, for example: Fernandez says she doubts there will be a clinic offering abortions opening in her town anytime soon. She sometimes wonders what happened to the women she used to help.

“Where did these women go? Where do they go now?” Fernandez says. “I don’t believe a lot of them found any other health care afterward.”

This story comes from NPR’s reporting partnership with KUT and Kaiser Health News.

A Young Immigrant Has Mental Illness, And That’s Raising His Risk of Being Deported

José’s son, who has schizophrenia, recently got into a fight that resulted in a broken window — an out-of-control moment from his struggle with mental illness. And it could increase his chances of deportation to a country where mental health care is even more elusive.

Hokyoung Kim for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Hokyoung Kim for NPR

When José moved his family to the United States from Mexico nearly two decades ago, he had hopes of giving his children a better life.

But now he worries about the future of his 21-year-old-son, who has lived in central Illinois since he was a toddler. José’s son has a criminal record, which could make him a target for deportation officials. We’re not using the son’s name because of those risks, and are using the father’s middle name, José, because both men are in the U.S. without permission.

José’s son was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder last year and has faced barriers to getting affordable treatment, in part because he doesn’t have legal status. His untreated condition has led to scrapes with the law.

Mental health advocates say many people with untreated mental illness run the risk of cycling in and out of the criminal justice system, and the situation is particularly fraught for those without legal status.

“If he gets deported he’d practically be lost in Mexico, because he doesn’t know Mexico,” says José, speaking through an interpreter. “I brought him here very young and, with his illness, where is he going to go? He’s likely to end up on the street.”

Legal troubles

José’s son has spent several weeks in jail and numerous days in court over the past year.

On the most recent occasion, the young man sat nervously in the front row of a courtroom in the Champaign County courthouse. Wearing a white button-down shirt and dress pants, his hair parted neatly, he stared at the floor while he waited for the judge to enter.

That day, he pleaded guilty to a criminal charge of property damage. The incident took place at his parents’ house earlier that year. He had gotten into a fight with his brother-in-law and broke a window. His father says it was yet another out-of-control moment from his son’s recent struggles with mental illness.

Before beginning proceedings, the judge read a warning aloud — something that is now standard practice to make sure noncitizens are aware that they could face deportation (or be denied citizenship or re-entry to the U.S.) if they plead guilty in court.

The young man received 12 months’ probation.

After the hearing, he agreed to an interview.

Just a couple of years ago, he says, his life was good: He was living on his own, working, and taking classes at community college. But all that changed when he started hearing voices and began struggling to keep his grip on reality. He withdrew from his friends and family, including his dad.

One time, he began driving erratically, thinking his car was telling him what to do. A month after that episode, he started having urges to kill himself and sometimes felt like hurting others.

In 2018, he was hospitalized twice, and finally got diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

José says that during this time, his son — who had always been respectful and kind — grew increasingly argumentative and even threatened to hurt his parents. The psychiatric hospitalizations didn’t seem to make a difference.

“He asked us for help, but we didn’t know how to help him,” José says. “He’d say, ‘Dad, I feel like I’m going crazy.’ “

José’s son says he met with a therapist a few times and was taking the medication he was prescribed in the hospital. He was also using marijuana to cope, he says.

The prescribed medication helped, he says, but without insurance, he couldn’t afford to pay the $180 monthly cost. When he stopped the meds, he struggled, and continued getting into trouble with the police.

Undocumented and uninsured

For people who are both undocumented and living with a mental illness, the situation is “particularly excruciating,” says Carrie Chapman, an attorney and advocate with the Legal Council for Health Justice in Chicago, who represents many clients like José’s son.

“If you have a mental illness that makes it difficult for you to control behaviors, you can end up in the criminal justice system,” Chapman says.

People with mental illness make up only a small percentage of violent offenders — they are actually more likely, compared to the general population, to be a victim of a violent crime.

Chapman says the stakes are extremely high when people without legal status enter the criminal justice system: they risk getting deported to a country where they may not speak the language, or where it’s even more difficult to obtain quality mental health care.

“It could be a death sentence for them there,” Chapman says. “It’s an incredible crisis, that such a vulnerable young person with serious mental illness falls through the cracks.”

An estimated 4.1 million adults under the age of 65 who live in the U.S. are ineligible for Medicaid or marketplace coverage under the Affordable Care Act because of their immigration status, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Among them are those who are undocumented and other immigrants who otherwise do not fall into one of the federal categories as lawfully in the U.S. People who are protected from deportation through the federal government’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, or DACA, also are ineligible for coverage under those programs.

For many people in all those groups, affordable health care is out of reach.

Some states have opened up access to Medicaid to undocumented children, including Illinois, California, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Washington and the District of Columbia, according to the National State Conference of Legislatures. But they lose that coverage at age 19, except in California, which recently expanded eligibility through age 25.

For those who can’t get access to affordable health insurance because of their undocumented status, medical care is largely limited to emergency services and treatments covered by charity care or provided by community health centers.

It’s unclear how many people have been deported because of issues linked to mental illness; good records are not available, says Talia Inlender, an attorney for immigrants’ rights with the Los Angeles-based pro bono law firm Public Counsel. But estimates from the ACLU suggest that tens of thousands of immigrants deported each year have a mental disability.

Inlender, who represents people who have mental health disabilities in deportation hearings, says when the lack of access to community-based treatment eventually leads to a person being detained in an immigration facility, that person risks further deterioration because many facilities are not equipped to provide the needed care.

On top of that, she says, immigrants facing deportation in most states don’t generally have a right to public counsel during the removal proceedings and have to represent themselves. Inlender points out that an immigrant with a mental disability could be particularly vulnerable without the help of a lawyer.

(Following a class-action lawsuit, the states of Washington, California and Arizona did establish a right to counsel for immigrants with mental illness facing deportation. For those in other states, there’s a federal program that tries to provide the same right to counsel, but it’s only for detained immigrants who have been properly screened.)

Medicaid for more people?

Chapman and other advocates for immigrants’ rights say expanding Medicaid to cover everyone who otherwise qualifies — regardless of legal status — and creating a broader pathway to U.S. citizenship would be good first steps toward helping people like José’s son.

“Everything else is kind of a ‘spit and duct tape’ attempt by families and advocates to get somebody what they need,” Chapman says.

Critics of the push to expand Medicaid to cover more undocumented people object to the costs, and argue that the money should be spent, instead, on those living in the country legally. (California’s move to expand Medicaid through age 25 will cost the state around $98 million, according to some estimates.)

As for José’s son, he recently found a pharmacy that offers a cheaper version of the prescription drug he needs to treat his mental health condition — so he’s back on medication and feeling better.

He now works as a landscaper and hopes to get back to college someday to study business. But he fears his criminal record could stand in the way of those goals, and he’s aware that his history makes him a target for immigration sweeps.

José says his greatest fear is that his son will end up back in Mexico — away from family and friends, in a country he knows little about.

“There are thousands of people going through these issues … and they’re in the same situation,” José says. “They’re in the dark, not knowing what to do, where to go, or who to ask for help.”

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with Side Effects Public Media, Illinois Public Media and Kaiser Health News. Christine Herman is a recipient of a Rosalynn Carter fellowship for mental health journalism. Follow her on Twitter: @CTHerman

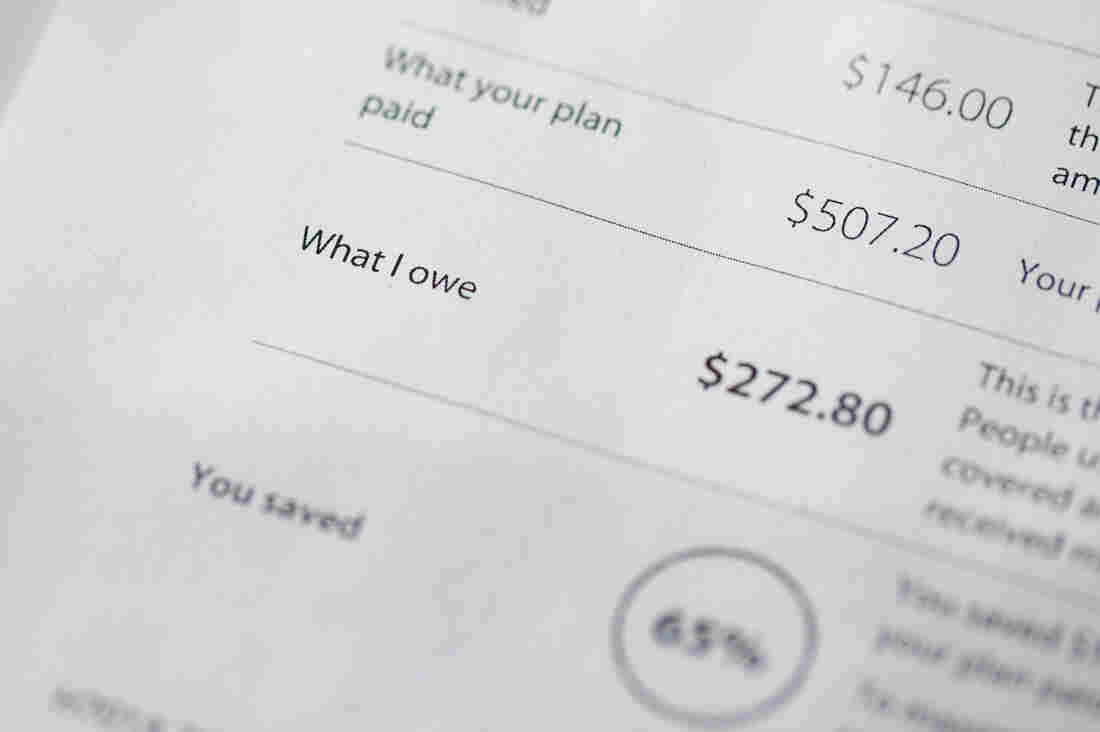

Trump Wants Insurers and Hospitals To Show Real Prices To Patients

One rule announced by the Trump administration Friday puts pressure on hospitals to reveal what they charge insurers for procedures and services. Critics say the penalty for not following the rule isn’t stiff enough to be a an effective deterrent.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Updated at 3:10 p.m. ET

President Trump has made price transparency a centerpiece of his health care agenda. Friday he announced two regulatory changes in a bid to provide more easy-to-read price information to patients.

The first effort targets hospitals, finalizing a rule that requires them to display their secret, negotiated rates to patients starting in January 2021. The second is a proposal to make insurance companies show patients their expected out-of-pocket costs through an online tool. That proposed rule is subject to 60 days of public comment, and it’s unclear when it would go into effect.

“Our goal is to give patients the knowledge they need about the real price of health care services,” said Trump. “They’ll be able to check them, compare them, go to different locations, so they can shop for the highest-quality care at the lowest cost.”

Administration officials heralded both rules as historic and transformative to the health care system.

“Under the status quo, health care prices are about as clear as mud to patients,” said Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma in a written statement. “Today’s rules usher in a new era that upends the status quo to empower patients and put them first.”

As NPR has reported, hospitals are currently required to post their “list prices” online, but that information has been very hard to use and doesn’t tell consumers much about what they are likely to pay. The new rule makes hospitals show what they really pay for services — not the list prices — and requires them to make that information easy to read and easy to access.

“I don’t know if the hospitals are going to like me too much anymore with this,” Trump said in a White House news conference Friday afternoon. “That’s OK.” He later added, “We’re stopping American patients from just getting — pure and simple, two words, very simple words — ripped off. Because they’ve been ripped off for years. For a lot of years.”

The second rule Trump announced Friday (which is a proposed rule, still subject to public comments before being finalized) affects insurance companies. It would essentially make insurers give patients their “explanation of benefits” upfront. It would require insurers to explain how much a service would cost, how much your plan would pay and how much you would owe — before the service is performed. The idea is that patients could use that information to shop around ahead of time for a better deal — assuming a better deal can be found, and the service isn’t a medical emergency.

Certainly these rules would give patients more information than they currently have. The other promise of these rules — that they will bring down health care costs — is more of an open question.

In public comments for the hospital rule, hospitals argued that having to make their negotiated rates public would backfire — if a hospital is charging less than another one nearby, it could theoretically raise its price to more closely match its competitor’s.

Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar dismissed that argument on a call with reporters Friday morning.

“This is a canard,” he said. “Point me to one sector of the American economy where the disclosure of having price information in a competitive marketplace actually leads to higher prices as opposed to lower prices.”

Larry Levitt, executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, pointed out on Twitter that the penalty for hospitals that defy Trump’s transparency rule was “quite weak.”

“A maximum fine of $300 per day,” he wrote. “The technical term for that is ‘chump change.’ I wonder how many hospitals will just pay the fine.”

There’s also an open question about whether these rules will survive legal challenges. Another Trump administration proposal to show drug list prices in television ads was blocked in the courts.

“We may face litigation, but we feel we’re on a very sound legal footing for what we’re asking,” Azar told reporters.

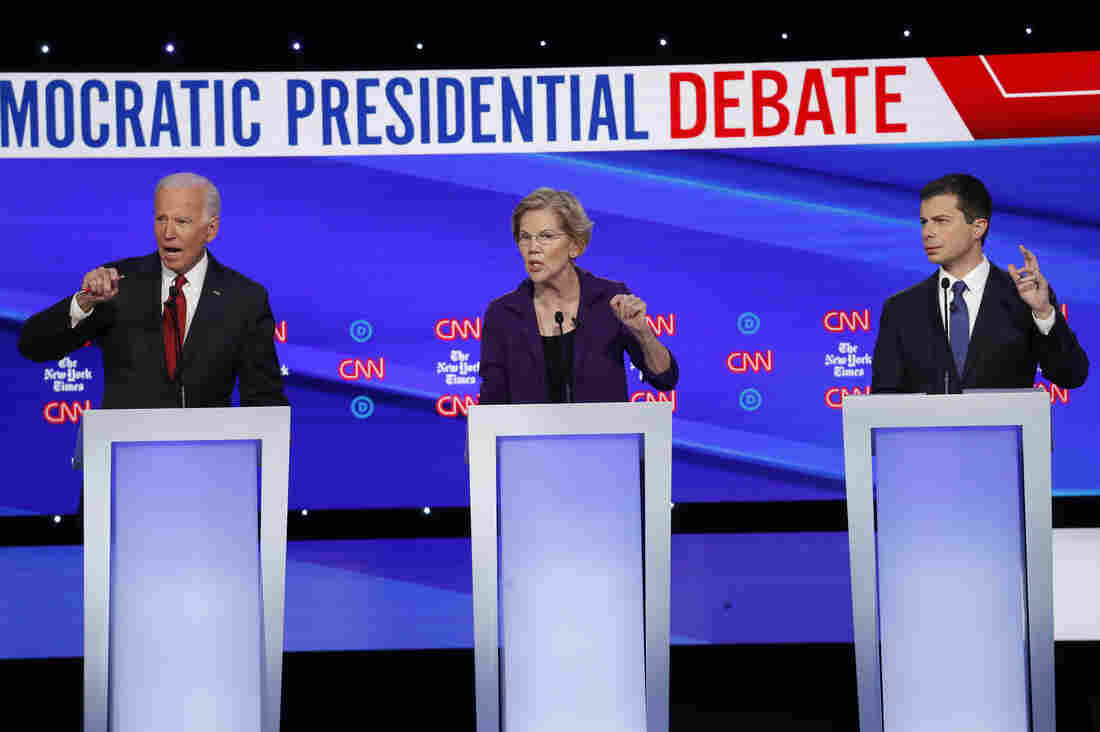

Why Even Universal Health Coverage Isn’t Enough

Democratic presidential candidates former Vice President Joe Biden (left), Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg (right) debate different ways to expand health coverage in America.

John Minchillo/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

John Minchillo/AP

The Democratic debate is less than a week away, and it’s likely that health care will once again take center stage. Once again, the candidates will spar over the best way to achieve universal coverage. Once again, the progressives will talk up the benefits of “Medicare For All” while the moderates attack it for its high cost and lack of choice. Just like the last debate. And the one before.

But it’s not the repetitiveness of the health care debate that bothers me. As a medical student, what bothers me is that the current health care debate is myopically focused on health insurance.

Although health insurance coverage is important, it’s only part of the picture. If the goal of our health care system is to keep Americans healthy, insurance will only get us so far. Health is about much more than access to health care.

Asthma triggers when you’re homeless

Take the case of a patient I helped treat this past summer, a young man in his early 20s who came into the emergency department experiencing severe shortness of breath. I could hear him wheezing before I even walked into the room.

He was sitting on the stretcher, breathing rapidly, and leaning forward with his hands on his knees — the classic “tripod” position signifying respiratory distress. After the resident physician and I determined he was having an asthma attack, we controlled his symptoms with steroids and inhalers and monitored him until he improved.

As I was preparing to discharge the patient, I briefed him on some of the asthma triggers he should avoid. When I advised him to keep the windows closed to minimize his exposure to pollen, he told me that the shelter where he was staying didn’t have air conditioning. It was 83 degrees outside that day.

Health insurance couldn’t prevent his next asthma attack. He needed a better and more stable housing situation.

Food deserts and no ride to the doctor

The same was true for a second patient of mine who was admitted to the hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of diabetes resulting from poor blood sugar control. After he recovered, we discharged him home to a food desert, a neighborhood where grocery stores and fresh-food markets are scarce and where following a low-carbohydrate diet is next to impossible. Health insurance cannot solve the food insecurity in his community.

Nor could health insurance enable a third patient of mine — who’d had vascular surgery to re-open a blocked artery in his leg — to return for his follow-up visit. Had he done so, we would have caught his post-operative infection early. As it happened, however, he had no way of traveling the 15 miles from his home to our clinic, and his infection worsened to the point that we had to amputate two of his toes. Health insurance didn’t address his transportation barriers.

Fortunately, all three patients were insured. Indeed, I’m grateful to attend medical school in Massachusetts, which has achieved near universal health insurance coverage. But sometimes insurance isn’t enough. I constantly see cases like these in which acute health problems arise due to factors seemingly unrelated to medicine. Universal coverage, while a worthy goal, does not translate into universal health.

Who will fix holes in the social safety net?

A recent study that rated U.S. counties based on health outcomes found that access to medical care accounted for only 20 percent of a county’s score. The other 80 percent was more readily attributable to social and economic factors like the ones affecting my patients, including housing instability, food insecurity, and access to transportation.

The health care dialogue in this political race has been dominated by the notion that we need to cover everyone, a principle I fully support. But even if we achieve that, it will only get us a fraction of the way to our goal of better health for all Americans. The German health care system is widely praised for its universal coverage, robust primary care, and low out-of-pocket costs for medical care. But it is nonetheless plagued with health disparities. In some cities, life expectancies of neighboring communities differ by up to 13 years.

To neglect these social factors in our public discourse on health care would be a mistake, not only because they are important to public health but also because policymakers are often better equipped to tackle social factors than they are medical ones. Evidence suggests that providing stable housing to homeless populations in urban areas, for instance, contributes to significantly reduced mortality.

Insurance coverage is a critical determinant of health. We should discuss it. But candidates for president should also discuss their plans to strengthen communities by addressing homelessness, food insecurity, and the other social factors that underpin America’s health gap.

Thus far, these issues have received scant attention in the Democratic primary race and in the larger political dialogue about health care. We need to broaden the conversation from a narrow discussion of health insurance to a holistic conversation about health.

Suhas Gondi is a third-year medical student at Harvard Medical School. A version of this essay originally appeared in Undark, the online science magazine.

Novelist Doctor Skewers Corporate Medicine In ‘Man’s 4th Best Hospital’

“The profession we love has been taken over,” psychiatrist and novelist Samuel Shem tells NPR, “with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.”

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

“Don’t read The House of God,” one of my professors told me in my first year of medical school.

He was talking about Samuel Shem’s 1978 novel about medical residency, an infamous book whose legacy still looms large in academic medicine. Shem — the pen name of psychiatrist Stephen Bergman — wrote it about his training at Harvard’s Beth Israel Hospital (which ultimately became Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) in Boston.

My professor told me not to read it, I imagine, because it’s a deeply cynical book and perhaps he hoped to preserve my idealism. Even though it has been more than 40 years since its publication, doctors today still debate whether it deserves its place in the canon of medical literature.

The novel follows Dr. Roy Basch, a fictional version of Shem, and his fellow residents during the first year of their medical training. They learn to deflect responsibility for challenging patients, put lies in their patients’ medical records and conduct romantic affairs with the nursing staff.

Basch’s friends even coin a term that is still in wide use in real hospitals today: Elderly patients with a long list of chronic conditions are still sometimes called “gomers,” which stands for “Get Out of My Emergency Room.”

Like any banned book, The House of God piqued my curiosity, and I finally read it this past year. I’m a family physician and a little over a year out of training, and I read it at the perfect time.

I got all the inside jokes about residency — and many were laugh-out-loud funny — but I am now far enough removed that the cynicism felt like satire rather than reality.

The House of God also felt dated. Basch and his cohort — who were, notably, all men, although not all white — didn’t have electronic medical records or hospital mergers to contend with. They wrote their notes about patients in paper charts. And it was almost quaint how much time the doctors spent chatting with patients in their hospital rooms.

It couldn’t be more different from my experience as a resident in the 21st century, which was deeply influenced by technology. There’s research to suggest that my cohort of medical residents spent about a third of our working hours looking at a computer — 112 of about 320 working hours a month.

In The House of God, set several decades before I set foot in a hospital, where were the smartphones? Where was the talk of RVUs — relative value units, a tool used by Medicare to pay for different medical services — or the push to squeeze more patients into each day?

That’s where Shem’s new book comes in. Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the fictional sequel to The House of God, and Basch and the gang are back together to fight against corporate medicine. This time the novel is set in a present-day academic medical center, and almost every doctor-patient interaction has been corrupted by greed and distracting technology.

Basch’s team has added a few more female physicians to its ranks, and together they battle a behemoth of an electronic medical record system. The hospital administrators in Shem’s latest book pressure the doctors to spend less time with every patient.

If The House of God is the great medical novel of the generation of physicians who came before me, perhaps Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the book for my cohort. It still has Shem’s zany brand of humor, but it also takes a hard look at forces that threaten the integrity of modern health care.

I spoke with Shem about Man’s 4th Best Hospital (which hit bookstores this week) and about his hopes for the future of medicine.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The protagonist in Man’s 4th Best Hospital, Dr. Roy Basch, doesn’t have a smartphone. I hear you don’t either. Why not?

If I had a smartphone, I would not be able to write any other novels. I have a bit of an addictive personality. I’d just be in it all the time. … I’ve got a flip phone. You can text me, but it has to be in the form of a question. I have this alphabetical keyboard. You either get an “OK” or an “N-O.”

A big theme in the novel is that technology has the potential to undermine the doctor-patient relationship. What made you want to focus on this?

I got a call out of the blue five years ago from NYU medical school. They said, “Do you want to be a professor at NYU med?” And I said, “What? Why?” And they said, “We want you to teach.” When I first got there, because I had been out of medicine [and hadn’t practiced since 1994], I figured, “Oh, I’ll look into what’s going on.” And I spent a night at Bellevue.

On the one hand, it’s absolutely amazing what medicine can do now. I remember I had a patient in The House of God [in the 1970s] with multiple myeloma. And that was a death sentence. We came in; we did the biopsy. He was dead. He was going to be dead. And that was that. Now it’s curable.

At Bellevue, I saw the magnificence of modern medicine. But like someone from Mars coming in and looking at this fresh, I immediately grasped the issues of money and effects of screens — computers’ and smartphones’.

And it just blew me away. It blew me away: the grandeur of medicine now and the horrific things that are happening to people who are really, sincerely, with love, trying to practice it. They are crunched, by being at the mercy of the financially focused system and technology.

In Man’s 4th Best Hospital, there’s a fair amount of nostalgia for the “good old days” of medicine in the 1960s and 1970s, before electronic medical records. What was better in that era?

If you ask doctors of my generation, “Why did you go into medicine?” they say, “I love the work. I really want to do good for people. I’m respected in the community, and I’ll make enough money.” Now: … “I want to have a good lifestyle.” Because you can’t make a ton of money in medicine anymore. You don’t have the respect of your community anymore. They may not even know much about you in a community because of all these [hospital] consolidations.

Do you think anything in medicine has gotten better?

The danger of isolation and the danger of being in a hierarchical system — students now are protected a lot more from that. When I was in training, interns were just so incredibly exhausted that they started doing really stupid things to themselves and patients. The atmosphere of training, by and large in most specialties, is much better.

You wrote an essay in 2002 titled “Fiction as Resistance,” about the power of novels to help make political and cultural change. What kind of resistance today can help fix American health care?

When somebody falls down, up onstage at a theater, do you ever hear the call go out, “Is there an insurance executive in the house?” No. If there are no doctors practicing medicine, there’s no health care. Doctors have to do something they have almost never done: They have to stick together. We have to stick together for what we want, in terms of the kind of health care we want to deliver, and to free ourselves from this computer mess that is driving everybody crazy, literally crazy.

Doctors don’t have a great track record of political activism, and only about half of physicians voted in recent general elections. What do you think might inspire more doctors to speak out?

Look at the difference between nurses and doctors. Nurses have great unions, powerful unions. They almost always win.

Doctors have never, ever formed anything like what the nurses have in terms of groups or unions. And that’s a big problem. So doctors somehow have to find a way — and under pressure, we might — to stick together. Doctors have to make an alliance with nurses, and other health care workers, and patients. That’s a solid group of people representing themselves in terms of what we think is good health care.

The profession we love has been taken over, with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.

Health care is a big issue for the upcoming election. What kind of changes are you hoping we’ll see?

There will be some kind of national health care system within five years. … You know, America thinks it has to invent things all over again all the time. Look at Australia. Look at France. Look at Canada. They have national systems, and they also have private insurance. Don’t get rid of insurance.

The two biggest subjects for the election are health care and health care. … The bad news is, it’s really hard to get done. The good news is, I think it’s inevitable. The good news is, it’s so bad it can’t go on.

One of the major criticisms of The House of God is that it’s sexist. It seems like your hero, Dr. Basch, has gotten a little more enlightened by the time of Man’s 4th Best Hospital. Does this reflect a change you’ve also experienced personally?

I was roundly criticized for the way women were seen in The House of God.

I remember the first rotation I had as a medical student at Harvard med was at Beth Israel, doing surgery. It got to be late at night, and I was trailing the surgeon around, and he went into the on-call room. There was a bunk bed there, and he started getting ready to go to bed. And I said, “Well, I’ll take the top bunk.” And he said, “You can’t sleep here.” So I left, and in walked a nurse. I was shocked.

Things have changed, and I am very, very glad. I don’t know if it seems conscious — I was very pleased to have total gender equity in the Fat Man Clinic [where the characters in Man’s 4th Best Hospital work] by the end of the book.

What made you feel like it was time to update The House of God?

I write to point out injustice as I see it, to resist injustice, and the danger of isolation, and the healing power of good connection. … We can help our patients to get better — but nobody has time to make the human connection to go along with getting them better.

Mara Gordon is a family physician in Camden, N.J., and a contributor to NPR. You can follow her on Twitter: @MaraGordonMD.