How HHS Secretary Alex Azar Reconciles Medicaid Cuts With Stopping The Spread Of HIV

HHS Secretary Alex Azar at a White House roundtable discussion of health care prices in January. Azar tells NPR his office is now in “active negotiations and discussion” with drugmakers on how to make HIV prevention medicines more available and “cost-effective.”

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

In his State of the Union address this year, President Trump announced an initiative “to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years.”

The man who pitched the president on this idea is Alex Azar, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

“We have the data that tells us where we have to focus, we have the tools, we have the leadership — this is an historic opportunity,” Azar told NPR’s Ari Shapiro Monday. “I told the president about this, and he immediately grabbed onto this and saw the potential to alleviate suffering for hundreds of thousands of individuals in this country and is deeply passionate about making that happen.”

Trump’s push to end HIV in the U.S. has inspired a mix of enthusiasm and skepticism from public health officials and patient advocates. Enthusiasm, because the plan seems to be rooted in data and is led by officials who have strong credentials in regards to HIV/AIDS. Skepticism, because of the administration’s history of rolling back protections for LGBTQ people, many of whom the program will need to reach to be successful.

For instance, transgender people are three times more likely to contract HIV than the national average, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trump has banned transgender people from serving in the military and undone rules that allow transgender students access to bathrooms that fit their gender presentation.

Azar himself has strong Republican credentials — as a young man, he clerked for Justice Antonin Scalia. And yet he’s now touring the country promoting this plan to end HIV, which includes supporting needle exchange programs to reduce HIV infection among intravenous drug users.

“Syringe services programs aren’t necessarily the first thing that comes to mind when you think about a Republican health secretary,” Azar acknowledged at an HIV conference last month. “But we’re in a battle between sickness and health — between life and death.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This morning you toured facilities in East Boston, a neighborhood in one of 48 counties targeted in Trump’s plan. What did you learn there?

I was able to be at the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center and they have a remarkable program called Project Shine. What I was able to do is meet with the entire team that provides this type of holistic approach. It is very much what we’re going to try to do in the most impacted areas.

You find the individuals who may have HIV — get them diagnosed. Get those who are diagnosed on the HIV antiretroviral treatment — so that they have an undetectable viral load and can’t spread the disease to others, as well as live a long healthy life themselves. Get those who are most at risk of contracting HIV on a medicine called PrEP so that they dramatically reduce their chance of getting HIV. And then, finally, respond when you have clusters of outbreaks. So, just getting to see the the holistic approach there was extremely helpful for me.

Given that Medicaid is the single largest payer for medical care for people with HIV, do Republican efforts to block Medicaid expansion in high-infection states like Mississippi and Alabama undermine your efforts to get more people treatment?

The program that we have is based on the assumption that Medicaid remains as it is. …. And even were we to change Medicaid, along the lines of what the president has proposed in the budget …

Meaning the major reductions to Medicaid that are in the president’s budget?

Well, there are there are some reductions. But what it would do is actually give states tremendous flexibility. One of the challenges in the Affordable Care Act was that it prejudiced the Medicaid system very much in favor of able-bodied adults, away from the more traditional Medicaid populations of the aged, the disabled, pregnant women and children.

What we would do is restore a lot of flexibility of the states so that they could put those resources really where they’re needed. We would expect that those suffering from HIV/AIDS infection would be in the core demographic of people that you would want to make sure were covered. What we will do here, by stopping the epidemic of HIV, is have a dramatic reduction in cost for the Medicaid and Medicare programs in the future.

So one big part of your plan is expanding access to PrEP, the HIV prevention drug. Without insurance it can cost around $1,600 a month in the U.S. A generic version available overseas costs roughly $6 a month. AIDS activists say your department could ‘march in’ and break the patent that Gilead holds in order to make a generic version available to Americans. Is your agency going to pursue that?

I don’t know what you’re saying by breaking the patent. There’s no such thing as a legal right to break patents in the United States …

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has a patent for PrEP, which Gilead disputes …

Well, that’s very different than breaking a patent. That would be asserting patent rights held by the CDC. So the CDC has a patent on the product and Gilead has a patent on the product. We are actually in active negotiations and discussion with Gilead right now on how we can make PrEP more available and more cost effective for individuals as part of this ending the HIV epidemic program.

I recently went to Jackson, Miss., which has one of the highest rates of HIV infection in the country. I talked to Shawn Esco, a black gay man, who told me that stigma, homophobia, and racism prevent people from seeking care, and he has very little hope. What would you say to him?

That is exactly what the president and I want to solve. I want to give him that hope. So many of the infections are happening in areas of our country where there’s intense stigma against individuals — males who have sex with men; the African-American community, Latino community, American Indian, Alaska Native communities. What’s really made this is a historic opportunity right now is we have data that show us that 50 percent of new infections are happening in 48 counties as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, and so we can focus those efforts.

We want to learn from people on the ground, as I did this morning here in East Boston. How do we reduce stigma? How do we provide a holistic approach for Shawn and others? We can get them diagnosed and get them on treatment in ways that they find acceptable — or, as one of the individuals said to me this morning, meet people where they are.

Drug Industry Middlemen To Be Questioned By Senate Committee

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, will lead the Senate Finance Committee’s questioning Tuesday of executives from pharmacy benefit managers about drug costs.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Win McNamee/Getty Images

Consumers, lawmakers and industry players all seem to agree that prescription drugs prices are too high. What they can’t always agree on is whom to blame.

On Tuesday, though, fingers are expected to point toward pharmacy benefit managers, the industry’s mysterious middlemen.

The Senate Finance Committee will hear from executives from the biggest pharmacy benefit managers, led by CVS Caremark and Cigna’s Express Scripts.

“They’re kind of a secret organization,” says Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, of the pharmacy benefit managers. “I ask people to explain what they’re doing and nobody seems to give you the same answer twice.” Grassley is chairman of the Finance Committee and Tuesday’s hearing is its third on drug prices this year.

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, manage prescription drug benefits for insurance companies and employers. And because they control the medication purchases of millions of patients, they are tremendously powerful.

“They exist only because pharmaceutical prices got so high and they were a way to get some market power in there that was on the consumer side,” says Len Nichols, a health economist at George Mason University. “Now they’ve become so big and dominant that they are hurting pharma.”

How dominant? CVS Caremark negotiates drug prices, copayments and which drugs are preferred options for more than 92 million people in the U.S. Express Scripts covers another 83 million.

The companies are hired by insurance companies, or self-insured employers, to control spending on prescription drugs. The PBMs negotiate discounts with pharmaceutical manufacturers, but those discounts come in the form of confidential rebates that are paid to the PBMs after the drugs are purchased.

PBMs pass most of the rebates on to their clients, but they often keep a slice for themselves.

The PBMs dispute that they are withholding savings from their clients. “While drug manufacturers would have people believe that PBMs are retaining these discounts, virtually all rebates and discounts are passed on to clients,” said Tom Moriarty, executive vice president at CVS Health, in a February speech.

Some analyses show that PBMs actually do help reduce drugs prices.

“PBMs have saved money over the last decade by encouraging use of generics,” says Dr. Walid Gellad, director of the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh.

A report from SSR Health, an investment research firm, says the net prices of brand-name prescription drugs fell 4.8 percent in the last quarter of 2018, even while list prices rose 4 percent. The declines came as pharmacy benefit managers refused to pay for some drugs altogether, opting for a competing brand that offered a better price.

Gellad says that evidence is murky, because the rebate system means that many drugs start at prices that are artificially high.

But critics say the system creates perverse incentives for drugmakers to set high prices for their products so they can offer larger percentage rebates. And they say sometimes PBMs benefit more when patients buy expensive drugs than when they buy cheaper ones.

Now the entire business model is under attack. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in February proposed eliminating the rebate system that underpins the work of companies like CVS Caremark and Express Scripts.

Instead, Azar proposed, the companies would use their market power to negotiate discounts from drugmakers upfront that would be passed on in full to patients.

In comments on HHS’ proposal to get rid of rebates, CVS said drugmakers — not PBMs — are to blame. “Our data show that it is not rebates that are causing drug prices to soar and, in fact, list price is increasing at a faster rate for many drugs with small rebates than for drugs with substantial rebates,” CVS wrote. “The elimination of rebates may not only lead to higher net drug prices, but will undoubtedly lead to higher premiums across the Medicare Part D program.”

Tuesday’s hearing comes six weeks after the leaders of seven pharmaceutical manufacturers appeared before the same committee to defend their pricing practices.

Those CEOs acknowledged that their prices are high for many patients, but they deflected blame onto pharmacy benefit managers.

“We want these rebates, which lower net prices, to benefit patients,” said Olivier Brandicourt, CEO of Sanofi, which makes Lantus, one of the highest priced brands of insulin. Its list price has risen from $244 to $431 since 2013, according to the committee.

“Unfortunately, under the current system, savings from rebates are not consistently passed through to patients in the form of lower deductibles, co-payments or coinsurance amounts,” Brandicourt said in testimony prepared for the hearing.

Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, who is the ranking member of the Finance Committee, had harsh words for the drug makers at the February hearing.

“I think you and others in the industry are stonewalling on the key issue, which is actually lowering list prices,” he said. “Lowering those list prices is the easiest way for consumers to pay less at the pharmacy counter.”

Grassley is also frustrated.

“The pharmaceutical companies pointed the finger at the PBMs. The PBMs point their finger at the pharmaceuticals. And then both of those are pointing their fingers at the at the health insurance companies,” Grassley said.

“I’m not announcing another hearing,” he continued. “But it might be that if we get this finger-pointing going on all the time, we may want to get those three groups all at the same table to stop the finger-pointing.”

Facing Escalating Workplace Violence, Hospitals Employees Have Had Enough

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, incidents of serious workplace violence are four times more common in health care than in private industry. Most assaults come from patients and patients’ families.

Phil Fisk/Cultura RF/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Phil Fisk/Cultura RF/Getty Images

Across the U.S., many doctors, nurses and other health care workers have remained silent about what is being called an epidemic of violence against them.

The violent outbursts come from patients and patient’s families. And for years, it’s been considered part of the job.

When you visit the Cleveland Clinic emergency department, these days —whether as a patient, family member or friend — a large sign directs you toward a metal detector.

An officer inspects all bags and then instructs you to walk through the metal detector. In some cases, a metal wand is used — even on patients who come in on stretchers. Cleveland Clinic officials say they confiscate thousands of weapons like knives, pepper spray and guns each year. The metal detectors were installed in response to what CEO Tom Mihaljevic is calling an epidemic.

“There is a very fundamental problem in U.S. health care that very few people speak about,” he says, “and that’s the violence against health care workers. Daily — literally, daily — we are exposed to violent outbursts, in particular in emergency rooms.”

Many health care workers say the physical and verbal abuse comes primarily from patients, some of whom are disoriented because of illness or from medication. Sometimes nurses and doctors are abused by family members who are on edge because their loved-one is so ill.

Cleveland Clinic also has introduced other safety measures — such as wireless panic buttons incorporated into I.D. badges, and more safety cameras and plain clothes officers in ERs.

But these incidents aren’t limited to emergency rooms.

Allysha Shin works as a registered nurse in neuroscience intensive care at the University of Southern California’s Keck Hospital in Los Angeles. One of the most violent incidents she’s experienced happened when she was caring for a patient who was bleeding inside her brain.

The woman had already lashed out at other staff, so she’d been tied to the bed, Shin said.

The woman broke free of the restraints and then kicked and punched Shin in the chest — before throwing punch at her face.

“There was this one point where she swung, and she had just glanced off the side of my chin. If I hadn’t dodged that punch she could have knocked me out,” Shin says. And she very well could have killed me.”

The encounter left Shin shaken and anxious when she returned to work days later. She still has flashbacks.

She used to be afraid to speak about these types of attacks, she says because of what she calls a culture of accepting violence in most hospitals.

“It is expected that you are going to get beat up from time to time,” Shin says.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, incidents of serious workplace violence are four times more common in health care than in private industry.

And a poll conducted by the American College of Emergency Physicians in 2018 found nearly half of emergency physician respondents reported being physically assaulted. More than 60 percent of them said the assault occurred within the previous year.

Groups representing doctors and nurses say while the voluntary safety improvements that some hospitals have enacted are a good first step, more needs to be done.

There is still a code of silence in healthcare, says Michelle Mahon, a representative of the labor group National Nurses United.

“So what happens if they do report it?” Mahon says. “In some cases, unfortunately, they are treated as if they are the ones who don’t know how to do their job. Or that’ it’s their fault that this happened.”

“There’s a lot of focus on de-escalation techniques,” Mahon adds. “Those are helpful tools, but oftentimes they are used to blame workers.”

In California, the nurse’s labor union pushed for a law giving OSHA more authority to monitor hospital safety. The group is now backing a national effort to do the same thing.

“The standard that we are recommending federally holds the employer responsible,” Mahon says. “It mandates reporting of incidents and transparency.”

The Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act, recently introduced in Congress, would require hospitals to implement plans to prevent violence. And any hospital could face fines for not reporting incidents to OSHA, Mahon adds.

The goal of the legislation — and of the union — is to hold administrators more accountable for acts of violence in their hospitals.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with Ideastream and Kaiser Health News.

Economic Ripples: Hospital Closure Hurts A Town’s Ability To Attract Retirees

Before it closed March 1, the 25-bed Columbia River Hospital, in Celina, Tenn., served the town of 1,500 residents. The closest hospital now is 18 miles from Celina — a 30-minute or more drive on mountain roads.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

When a rural community loses its hospital, health care becomes harder to come by in an instant. But a hospital closure also shocks a small town’s economy. It shuts down one of its largest employers. It scares off heavy industry that needs an emergency room nearby. And in one Tennessee town, a lost hospital means lost hope of attracting more retirees.

Seniors, and their retirement accounts, have been viewed as potential saviors for many rural economies trying to make up for lost jobs. But the epidemic of rural hospital closures is threatening those dreams in places like Celina, Tenn.. The town of 1,500, whose 25-bed hospital closed March 1, has been trying to position itself as a retiree destination.

“I’d say, look elsewhere,” says Susan Scovel, a Seattle transplant who came with her husband in 2015.

Scovel’s despondence is especially noteworthy given that she leads the local chamber of commerce effort to attract retirees like herself. She considers the wooded hills and secluded lake to hold comparable scenic beauty to the Washington coast — with dramatically lower costs of living; she and a small committee plan getaway weekends for prospects to visit.

When she first toured the region before moving in 2015, Scovel and her husband, who had Parkinson’s, made sure to scope out the hospital, on a hill overlooking the sleepy town square. And she’s rushed to the hospital four times since he died in 2017.

“I have very high blood pressure, and they’re able to do the IVs to get it down,” Scovel says. “This is an anxiety thing since my husband died. So now — I don’t know.”

She says she can’t in good conscience advise a senior with health problems to come join her in Celina.

Susan Bailey has lived most of her life in Celina and started her nursing career at Cumberland River Hospital. She now worries that its closure will drive away the town’s remaining physicians.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

The closure adds delays when seconds count

Celina’s Cumberland River Hospital had been on life support for years, operated by the city-owned medical center an hour away in Cookeville, which decided in late January to cut its losses after trying to find a buyer. Cookeville Regional Medical Center explains that the facility faced the grim reality for many rural providers.

“Unfortunately, many rural hospitals across the country are having a difficult time and facing the same challenges, like declining reimbursements and lower patient volumes, that Cumberland River Hospital has experienced,” CEO Paul Korth said in a written statement.

Celina became the 11th rural hospital in Tennessee to close in recent years — more than in any state but Texas. Both states have refused to expand Medicaid in a way that covers more of the working poor. Even some Republicans now say the decision to not expand Medicaid has added to the struggles of rural health care providers.

The closest hospital is now 18 miles away. That adds another 30 minutes through mountain roads for those who need an X-ray or blood work. For those in the back of an ambulance, that bit of time could make the difference between life or death.

Staff members posted photos and other memorabilia in the halls — reminders of happier times — in the weeks before its closure.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

“We have the capability of doing a lot of advanced life support, but we’re not a hospital,” says emergency management director Natalie Boone.

The area is already limited in its ambulance service, with two of its four trucks out of service.

Once a crew is dispatched, Boone says, it’s committed to that call. Adding an hour to the turnaround time means someone else could likely call with an emergency and be told — essentially — to wait in line.

“What happens when you have that patient that doesn’t have that extra time?” Boone asks. “I can think of at least a minimum of two patients [in the last month] that did not have that time.”

Residents are bracing for cascading effects. Susan Bailey hasn’t retired yet, but she’s close. She’s spent nearly 40 years as a registered nurse, including her early career at Cumberland River.

“People say, ‘You probably just need to move or find another place to go,’ ” she says.

Closure of the hospital meant 147 nurses, aides and clerical staff had to find new jobs. The hospital was the town’s second-largest employer, after the local school system.

Blake Farmer/WPLN

hide caption

toggle caption

Blake Farmer/WPLN

Bailey and others are concerned that losing the hospital will soon mean losing the only three physicians in town. The doctors say they plan to keep their practices going, but for how long? And what about when they retire?

“That’s a big problem,” Bailey says. “The doctors aren’t going to want to come in and open an office and have to drive 20 or 30 minutes to see their patients every single day.”

Closure of the hospital means 147 nurses, aides and clerical staff have to find new jobs. Some employees come to tears at the prospect of having to find work outside the county and are deeply sad that their hometown is losing one of its largest employers — second only to the local school system.

Dr. John McMichen is an emergency physician who would travel to Celina to work weekends at the ER and give the local doctors a break.

“I thought of Celina as maybe the Andy Griffith Show of health care,” he says.

McMichen, who also worked at the now shuttered Copper Basin Medical Center, on the other side of the state, says people at Cumberland River knew just about anyone who would walk through the door. That’s why it was attractive to retirees.

“It reminded me of a time long ago that has seemingly passed. I can’t say that it will ever come back,” he says. “I have hopes that there’s still some hope for small hospitals in that type of community. But I think the chances are becoming less of those community hospitals surviving.”

Researchers Are Surprised By The Magnitude Of Venezuela’s Health Crisis

Things in Venezuela are so bad that patients who are hospitalized must bring not only their own food but also medical supplies like syringes and scalpels as well as their own soap and water, a new report says.

Barcroft Media/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Barcroft Media/Getty Images

Venezuela is in the midst of “a major, major emergency” when it comes to health.

That’s the view of Dr. Paul Spiegel, who edited and reviewed a new report from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the international group Human Rights Watch. Released this week, the study outlines the enormity of the health crisis in Venezuela and calls for international action.

The health crisis began in 2012, two years after the economic crisis began in 2010. But it took a drastic turn for the worse in 2017, and the situation now is even more dismal than researchers expected.

“It is surprising, the magnitude,” says Spiegel, who is director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Humanitarian Health and a professor in the Department of International Health at the Bloomberg School. “The situation in Venezuela is dire.”

Things are so bad that, according to the report and other sources, patients who go to the hospital need to bring not only their own food but also medical supplies like syringes and scalpels as well as their own soap and water.

“The international community must respond,” Spiegel says. “Because millions of people are suffering.”

The government of Venezuela stopped publishing health statistics in 2017, so it can be difficult to track exactly how bad the crisis is. But by interviewing doctors and organizations within Venezuela, as well as migrants who recently fled the country and health officials in neighboring Colombia and Brazil, the researchers pieced together a detailed picture of the failing health system. Some of the data also come from the last official government health report, issued in 2017. (The health minister who released the report was promptly fired.)

Diseases that are preventable with vaccines are making a major comeback throughout the country. Cases of measles and diphtheria, which were rare or nonexistent before the economic crisis, have surged to 9,300 and 2,500 respectively.

Since 2009, confirmed cases of malaria increased from 36,000 to 414,000 in 2017.

The Ministry of Health report from 2017 showed that maternal mortality had shot up by 65 percent in one year — from 456 women who died in 2015 to 756 women in 2016. At the same time, infant mortality rose by 30 percent — from 8,812 children under age 1 dying in 2015 to 11,466 children the following year.

The rate of tuberculosis is the highest it has been in the country in the past four decades, with approximately 13,000 cases in 2017.

New HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths have increased sharply, the researchers write, in large part because the vast majority of HIV-positive Venezuelans no longer have access to antiretroviral medications.

A recent report from the Pan American Health Organization estimated that new HIV infections increased by 24 percent from 2010 to 2016, the last year the government published data. And nearly 9 out of 10 Venezuelans known to be living with HIV (69,308 of 79,467 people) were not receiving antiretroviral treatments.

In addition, the lack of HIV test kits may mean there are Venezuelans who are living with HIV but don’t know it.

Cáritas Venezuela, a Catholic humanitarian organization, found that the percentage of children under 5 experiencing malnutrition had increased from 10 to 17 percent from 2017 to 2018 — “a level indicative of a crisis, based on WHO standards,” the authors of the report write.

An estimated 3.4 million people — about a tenth of Venezuela’s entire population — have left the country in recent years to survive. Venezuela’s neighbors, particularly Colombia and Brazil, have seen a huge uptick in Venezuelans seeking medical care.

Health officials in those countries say that thousands of pregnant women who have arrived received no prenatal care in Venezuela. The flow of migrants includes hundreds of children suffering from malnutrition.

Despite all the headlines about Venezuela’s collapse, researchers were still surprised by the scope of the crisis.

Venezuela is a middle-income country with a previously strong infrastructure, Spiegel says. “So just to see this incredible decline in the health infrastructure in such a short period of time is quite astonishing.”

Despite the severity of the health crisis, the government continues to paint a rosy picture of its health care system — and to retaliate against anyone who reports otherwise, according to the report.

Dr. Alberto Paniz Mondolfi, who was not affiliated with the report, spoke with NPR about the situation in his home country. Paniz practices in Barquisimeto, Venezuela, and is a member of the Venezuelan National Academy of Medicine.

Paniz says he has seen children in hospitals who appear to be malnourished — and there aren’t even catheters available to hook them up to IVs. He has seen people on the streets searching the trash for food to eat. And he adds that a blackout that began on March 7 and lasted for a week has had lingering impact: Some areas still lack electricity or access to running water even now, he says.

Paniz says the report from Johns Hopkins and Human Rights Watch paints an accurate picture of the situation on the ground. “It’s a very, very timely and complete paper,” he says. He praised the thorough research and said he was “relieved” that the health crisis might finally get international attention.

So far, aid from the U.S. and other countries has been insufficient to address the crisis, the authors of this report say.

But Spiegel sees some signs of hope: Last week, President Nicolás Maduro decided to allow the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent to enter the country with medical supplies for about 650,000 people.

“It’s still a drop in the bucket compared to the 7 million or so people who are in desperate need,” Spiegel says. But he believes it is a sign that Venezuela’s leader may begin acknowledging the crisis and opening the country up to assistance.

And the good news, Spiegel says, is that once aid arrives in Venezuela, it can be distributed very quickly. “Venezuela has an infrastructure; it has very well trained people,” he says.

Paniz agrees that international assistance will be crucial to ending the crisis. “It’s a desperate call to not leave us alone,” he says. “There is no way in which Venezuela could come out of this by its own.”

Melody Schreiber (@m_scribe on Twitter) is a freelance journalist in Washington, D.C.

Makeshift Volunteer Clinics Struggle To Meet Medical Needs At The Border

Dr. Carlos Gutierrez examines a young girl at a shelter in El Paso that was set up for recent migrants. The girl’s mother said her daughter’s deep cough arose while the family was in immigration custody.

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

It wasn’t the rash covering Meliza’s feet and legs that worried Dr. José Manuel de la Rosa. What concerned him were the deep bruises beneath. They were a sign she could be experiencing something far more serious than an allergic reaction.

Meliza’s mom, Magdalena, told the doctor it started with one little bump. Then two. In no time, the 5-year-old’s legs were swollen and red from the knees down.

U.S. immigration officials are releasing up to 700 people a day into El Paso, Texas. Ciudad Juárez, in Mexico, can be seen in the distance.

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

De la Rosa noticed a bandage-covered cotton ball in the crook of Meliza’s elbow, a remnant of having blood drawn. During their time at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facility in El Paso, Meliza had been sent to a hospital, Magdalena explained, cradling the child. They had run tests, but Magdalena had no way to get the results. Through tears, she begged for help. “My daughter is my life,” she told him in Spanish.

The doctor would see nearly a dozen patients that March evening at his makeshift clinic inside a warehouse near the El Paso airport. That week, similar ad hoc community clinics would treat hundreds of people, some with routine colds and viruses, others with upper-respiratory infections or gaping wounds. Like Meliza, all were migrants, mostly from Central America, a river of families arriving each day, many frightened and exhausted after days spent in government detention.

De la Rosa, an El Paso pediatrician, is one of dozens of doctors volunteering on the U.S.-Mexico border as the flow of migrants crossing without papers and asking for asylum climbs to a six-year high. Unlike previous waves of immigration, these are not single men from Mexico looking to blend in and find work.

Most are families, fleeing gang violence, political instability or dire poverty. (Meliza and other patients are referred to by their first or middle names in this story because of their concerns that speaking to the news media could affect their asylum cases.)

President Trump has declared a national emergency on the southwestern border to free up billions of dollars in funding to construct a wall as a means of stemming the tide of asylum seekers. He is expected to make an appearance in Calexico, Calif., Friday to tour a 30-foot section of fence that was rebuilt last year.

But the federal government isn’t covering the cost of the humanitarian crisis unfolding in border communities like El Paso.

In the absence of a coordinated federal response, nonprofit organizations across the 1,900-mile stretch have stepped in to provide food, shelter and medical care.

Border cities like El Paso, McAllen, Texas, and San Diego are used to relying on local charities for some level of migrant care. But not in the massive numbers and sustained duration they’re seeing now. As the months drag on, the work is taking a financial and emotional toll. Nonprofit operators are drawing on donations, financial reserves and the generosity of medical volunteers to meet demand. Some worry this “new normal” is simply not sustainable.

“The care we are providing we could never have foreseen — or imagined spending what we are spending,” said Ana Melgoza, vice president of external affairs for San Ysidro Health, a community health system providing care for migrants crossing into San Diego. She said her clinic has spent nearly $250,000 on such care since November.

At an ad hoc clinic in an old warehouse in El Paso, Dr. José Manuel de la Rosa discusses an insulin prescription with a woman who has diabetes.

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

An emotional and financial toll

In October, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency drastically changed how it handles migrant releases from its detention facilities. Families seeking asylum no longer would get help coordinating travel to live with relatives or sponsors while claims were processed. Since the policy shift, thousands of migrants have found themselves in border cities without money, food or a way to communicate with family. From Dec. 21 to March 21, 107,000 people were released from ICE detention to await immigration hearings.

In El Paso, which has seen a 1,689 percent increase in border apprehensions of migrants traveling with family members compared with last year, volunteer doctors are staffing a network of clinics. Kids with coughs and colds, diarrhea and vomiting are common. Some migrants have severe blisters on their feet that need cleaning, or diabetes that’s out of control because, they say, their insulin was thrown away by border patrol agents.

For de la Rosa, this is just the latest work in a career tied to border health. Born and raised in El Paso, he has served on the U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission since President George Bush appointed him in 2003. He was founding dean of the city’s Paul L. Foster School of Medicine when it opened a decade ago as one of the few programs in the country that requires all students to take courses in “medical Spanish,” designed to bolster communication with Spanish-speaking patients.

As he entered the warehouse-turned-shelter that evening in late March, he pulled off his signature bow tie and draped a stethoscope around his neck. He thinks it’s a gift to be able to help people who would otherwise have no way to get care. “Sometimes I don’t know if I’m doing it for me or for them,” he said. “It is so fulfilling.”

But cases like Meliza’s are frustrating for the doctors, because they can’t see them through.

After passing an initial screening to claim asylum, Meliza and her mother had been taken to the warehouse, where volunteers gave them food and a bed, and helped arrange travel to South Carolina, where they could live with a family member as their asylum claim proceeds.

Meliza’s rash began while they were in detention, Magdalena told de la Rosa. And four days in, she was sent to a hospital. But they were released from custody before getting the test results. De la Rosa called the hospital, hoping the labs would offer clues as to whether the girl might have leukemia; Henoch-Schonlein purpura (a disorder that can cause kidney damage); or just an allergic reaction. The hospital asked de la Rosa for a privacy waiver from the mother, but by the time he could return to the shelter for her signature, she had boarded a bus for South Carolina. That would be the last he saw of her.

‘The best we can do’

Born and raised in El Paso, De la Rosa has served on the U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission since President George Bush appointed him in 2003. Helping migrants get the health care they need is fulfilling he says. But many days he’s frustrated and overwhelmed by the lack of government support.

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

Dr. Carlos Gutierrez, another El Paso pediatrician, is also desperate for communication with the doctors who work inside the detention facilities. When people are released with complicated health issues — like a man who recently showed up with a flesh-eating bacterial infection and a wound so big they could see his bone — the volunteer doctors often have to start from scratch, trying to determine what a patient has and what treatment they’ve been given.

For much of the past five months, Gutierrez has used the lunch break from his private pediatric clinic to see migrants. He works in one of several hotels being rented out by Annunciation House, a nonprofit that runs the area’s main shelter network.

The organization, which is funded through donations from religious organizations and individuals, has dug deep, spending more than $1 million on hotels in the past four or five months, its executive director said at a city council meeting. It struggles to accommodate everyone — Annunciation House recently scrambled to open a temporary shelter so that 150 people wouldn’t have to sleep in a city park.

On his way to the hotel, Gutierrez reviewed the day’s text message from the organization’s director outlining how many refugees would be arriving that day: 510.

The first patients treated that day in his improvised clinic — set up in a hotel room bathroom — were 9-year-old twins from Guatemala. They were traveling with their mother, Mirian, who said she fled her hometown after local men threatened to kidnap one daughter if she didn’t pay protection money to operate her tortilla stand.

Mirian and her daughters had crossed a small river to reach what she believed was New Mexico, she said, imagining that the authorities they surrendered to would be like the U.S. tourists she’d met in her hometown. “There, when the tourists arrive, they are so nice. Even doctors come to help us,” she said in Spanish.

But the welcome in the U.S. was not warm. During the six days the family spent in federal custody, one of her daughters contracted bronchitis, Mirian told Gutierrez. They were healthy when they entered, she said, but sleeping on cold concrete floors and eating skimpy ham and cheese sandwiches broke them down. “They treat you as if you’re trash,” she said.

Mirian showed Gutierrez an inhaler she was given in the detention facility and asked what it was for. Her other daughter had developed a deep cough and needed attention, she said. After examining both girls, Gutierrez explained about the inhaler, and showed Mirian how to help her daughter use it. The girls would be fine, he told her, but with their lungs as congested as they were, it might be weeks before they recovered.

“I mean, this is the best we can do,” Gutierrez said, after prescribing an antibiotic to a little girl with an ear infection. “We could be doing it better. But when they are in our care nobody is dying.”

De la Rosa examines a rash on the foot of a 5-year-old girl named Meliza. Though he believed it was likely a sign of an allergic reaction, the underlying bruising could also signal serious infection or leukemia, he worried. Before he could get the test results he needed, the family was gone.

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Maria Barry-Jester/Kaiser Health News

Necessary work

More than two dozen people have died while in immigration custody under the Trump administration, according to a calculation based on a recent NBC News analysis. The government says it added nurses and doctors to its facilities after two children died in December. Immigration authorities are now taking 60 children a day to the hospital and doing medical screens for every child under 18, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol Commissioner Kevin McAleenan said during a March news conference.

But many people still have serious needs upon release. When Gutierrez and his colleagues started these clinics, they were meant to temporarily fill a gap caused by the change in government policy. Asked if he thinks the volunteer work is sustainable, he shook his head and sighed. “I’m so tired.”

The financial model — relying on donations and volunteers — also has its limits. Asylum seekers generally don’t qualify for social services, including Medicaid, before they have been granted asylum. In California, negotiations are underway to make some of the $5 million in emergency funds the state is spending at the border available to reimburse clinics for care, according to the office of state Sen. Toni Atkins. Physicians in Texas and Arizona were not aware of similar conversations in their states.

Dr. Blanca Garcia, another El Paso pediatrician, has been volunteering a few days a week since October. Like many of the doctors, she cites a moral and financial argument for providing care to the migrants, who are in the country legally once they apply for asylum. These are vulnerable people who might not otherwise seek care, and for every diagnosis of strep throat, she is likely preventing an expensive emergency room visit, she said.

Still, there are limitations to what they can provide.

Cristian, 21, and his 5-month-old baby, Gretel, arrived at an El Paso shelter in a former assisted living facility early one afternoon. He’d never been alone this long with his daughter, he said. His wife — a minor — had been separated from them at the border, put in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services. Cristian didn’t know when she might be released.

While in detention, he had spent several nights with Gretel on a concrete floor in a room with more than a hundred other men, he said. He asked a guard for a better sleeping situation. Instead of receiving help, he said, he was punished by being forced to sit and stare at a wall for over an hour as Gretel cried in his arms.

Still breastfeeding before she was separated from her mother, she would suck on his nose and at his shirt. He was worried that she wasn’t getting enough to eat, and that the formula he was giving her wasn’t as good for her as breastmilk. Dr. Garcia told him the baby looked healthy.

Still, Cristian was anxious, and grew increasingly distressed as he recounted their history.

“Will the baby be OK?” he asked in Spanish.

She assured the young father he was doing everything he could.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

How 128,000 Low-Income Kids Lost Health Care In Tennessee Over 2 Years

NPR’s Audie Cornish speaks with Nashville Tennessean reporter Brett Kelman about why Tennessee’s health insurance programs dropped more than 100,000 low-income children from the rolls over two years.

Opinion: Direct-To-Consumer Medicine Can Be Quick And Discreet, But What’s Lost?

If a doctor’s office is like Blockbuster, Hims feels more like Netflix. It’s a way to skip the long waits and crowds and get generic Viagra, hair growth treatment and other medicine and vitamins with minimal interaction with a health care provider — for better and worse.

PeopleImages/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

PeopleImages/Getty Images

If you’re on Instagram or if you’ve taken the New York City subway lately, chances are you’ve heard of Hims, the men’s health and wellness company with a penchant for advertisements featuring suggestive cacti and eggplants against pastel backgrounds. The Web-based startup targets the young male demographic with skin care products, multivitamins and erectile dysfunction medications.

In January, just a few months after its first birthday, the company joined Silicon Valley’s vaunted “unicorn” club: It received a venture-capital investment that put its valuation at $1 billion.

The ambitious valuation is certainly a remarkable achievement for the young company. But it’s also yet another signal that a new e-commerce market that one might call “direct-to-consumer medicine” is on the rise.

Although the companies in this sector have different styles and specialties, they all aim to connect patients, pharmacies and doctors through apps and the cloud. Their core business models are remarkably similar. First, a self-diagnosing consumer selects a product they think they need. Then, the customer completes an online questionnaire, which is reviewed by a physician if a prescription is needed. A secure messaging platform is available if the customer has questions for the physician before the order is filled and mailed to their door.

These direct-to-consumer companies have historically occupied the periphery of American health care, offering services that often aren’t covered by traditional medical insurance. For instance, there’s Hubble for vision testing and contact lens prescriptions, SmileDirectClub for mail-order orthodontics, and Keeps for hair loss.

But as younger consumers express a growing preference to shop for products and services online, the industry has started to encroach into the territory of traditional primary care. Consumers can turn to Hims and Roman for erectile dysfunction, to Nurx for oral contraception, to Cove for migraines, and to Zero to quit smoking. As more drugs have gone generic, the trend has accelerated and investors have grown more eager to get in the game.

As a medical student who just finished a rotation in a primary care office, I can see the appeal. Hims in particular has potential to bring stigmatized men’s health topics out of the shadows and connect men to affordable treatments for conditions that they otherwise might not address.

Direct-to-consumer medicine is certainly more convenient and discreet than a trip to a doctor’s office, where patients commonly endure long waits only to be rushed through a conversation with a physician who’s weighed down by too many obligations. If a doctor’s office is like Blockbuster, Hims feels more like Netflix.

But I also question whether direct-to-consumer medicine is truly safe for patients. Take erectile dysfunction, or ED. On paper, it seems like a simple diagnosis. In reality, however, it’s a textbook example of the complexity of human health. Sometimes ED occurs on its own, with no identifiable cause. But more often than not, it is a symptom or precursor of other conditions: anxiety, depression, clogged blood vessels, high blood pressure, diabetes or hormone imbalances.

That’s why the American Urological Association advises physicians treating patients with ED to also screen for the condition’s potential physical, social and behavioral causes, including relationship issues and drinking and smoking habits. The association recommends, at the very least, checking vitals, performing a genital exam and for patients presenting with ED issues for the first time, screening for high cholesterol, diabetes and other diagnoses commonly associated with ED.

For some direct-to-consumer health products, like oral contraception (now offered by companies such as Hers, a subsidiary of Hims), an online evaluation may be sufficient. But Hims’ evaluation for ED appears to fall far short of the basic AUA guidelines.

The direct-to-consumer companies also present ethical dilemmas. The physicians who work for them may be hamstrung in terms of the scope of the advice they can offer and their ability to follow up with patients to track progress. And they surely must feel some pressure to push their employer’s products. The companies essentially operate on islands of care, where doctors can’t address secondary issues that surface during a consultation and can’t add information to a patient’s home medical record.

There’s also the risk of muddying the critical distinction between health and wellness: Hims’ marketing and website design places FDA-approved drugs like propranolol — commonly used off-label to treat performance anxiety — alongside supplements like biotin gummies, conflating the two categories for unwitting consumers.

One could argue that direct-to-consumer medical startups and their venture capital investors are attempting to disrupt primary care by “unbundling” it. This goal contrasts with the vision of primary care enshrined in legislation like the Affordable Care Act, which championed a “patient-centered medical home” where a strong physician-patient relationship is supported by ancillary professionals. Instead, the e-commerce model takes the view that physicians are middlemen clinging to an industry ripe for change — much like taxicabs, bookstores and hotels in the days before Uber, Amazon and Airbnb.

In this technocratic, patient-empowered dream, however, I can’t help but wonder what is lost. During my primary care rotation, I would always begin conversations with patients by asking what prompted their visit. Yet the conversation hardly ever ended there. Our agenda was dynamic, hinged to the information gathered in real time in the exam room.

Frequently, we would shift gears to discuss a patient’s previous diagnoses, to address new concerns such as high blood pressure readings, or to talk about plans for end-of-life care. We often discussed evidence-based preventive measures — like options for eating healthier, methods to quit smoking or guidelines for colon cancer screening. In other words, we would not only act on the concerns of the present, but also anticipate the needs of the future.

In many ways, Hims and other startups are capitalizing on a cultural moment. Their products address a genuine frustration with the current state of American health care, and they are emblematic of what’s likely to be a lasting trend toward commodification in medicine. The companies’ early successes are arguably a smoke signal for traditional primary care — a warning that doctors’ offices must adapt to become less clunky and bureaucratic.

The question of whether companies like Hims and Roman are heroes or villains of the health care ecosystem continues to be hotly debated. Christina Farr, a reporter for CNBC, recently tweeted that the rise of personal wellness startups was “the most divisive trend” she has seen in her years covering health and technology.

I would like to think there is room for both health care models to coexist. Considering how big the direct-to-consumer market has become, today’s primary care physicians have a pragmatic obligation to ask patients if they use online wellness companies, to understand which products they offer and to counsel patients on the potential risks and benefits of those products. If these companies are leveraged correctly, they very well could declutter primary care and break down barriers to access. But we should push for greater regulation to address potential ethical concerns, draw clear distinctions between health and wellness, and establish guidelines that protect our patients.

As more startups like Hims take root, the window of opportunity to set the rules of direct-to-consumer medicine will close. The time to act is now.

Vishal Khetpal is a freelance writer and third-year medical student at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. A version of this essay originally appeared in Undark, the online science magazine.

Express Scripts Takes Steps To Cut Insulin’s Price To Patients

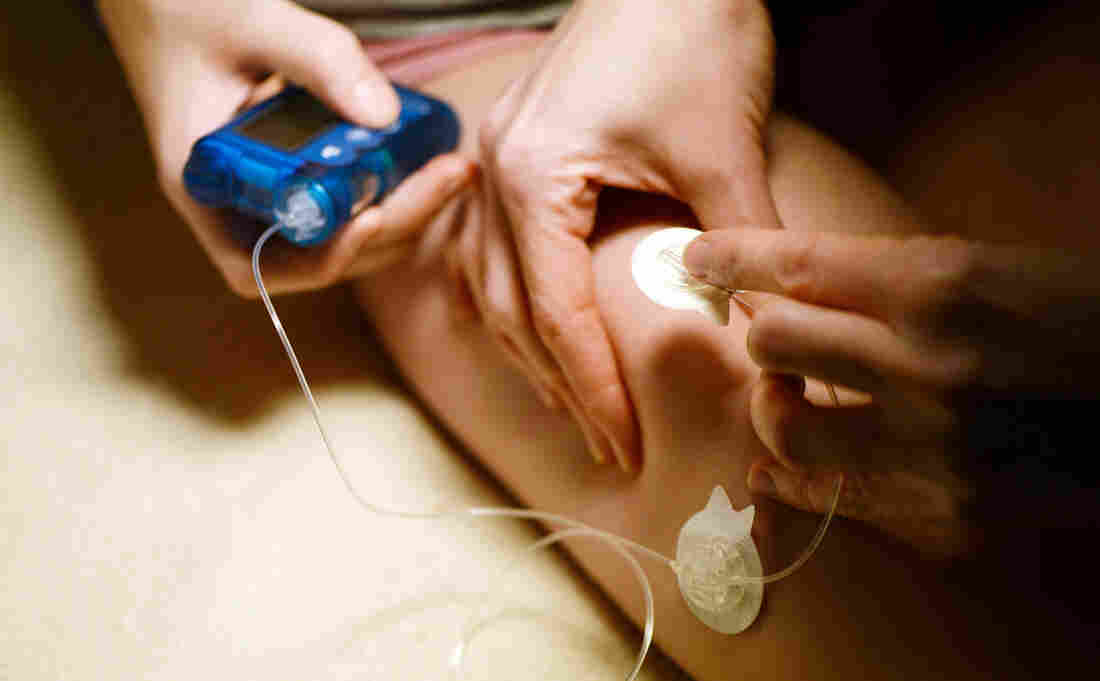

A medical assistant administers insulin to an adolescent patient who has Type 1 diabetes. Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, says it covers 1.4 million people who take insulin.

Picture Alliance/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Picture Alliance/Getty Images

As the heat turns up on drug manufacturers who determine the price of insulin and the health insurers and middlemen who determine what patients pay, one company — Cigna’s Express Scripts — announced Wednesday it will take steps by the end of the year to help limit the drug’s cost to consumers.

Express Scripts, which manages prescription drug insurance for more than 80 million people, is launching a “patient assurance program” that Steve Miller, Cigna’s chief clinical officer, says “caps the copay for a patient at $25 a month for their insulin — no matter what.”

The move by Express Scripts comes as lawmakers are focused on high drug prices and listening to stories about patients who can’t afford their medication.

Insulin has become a major focus. A Minnesota man died last year, according to his mother, when he tried to ration his insulin because he couldn’t afford the $1,300 monthly cost.

Though the drug has been in use for more than a century, its price in the U.S. is 10 times higher than it was 20 years ago, according to a report by the House of Representatives released last week.

“What we’re hoping is that we’re going to see more diabetics taking more insulin, [fewer] complications for those patients, and hopefully lower health care costs,” Miller tells Shots.

Express Scripts covers 1.4 million people who take insulin, Miller says.

Under the discount program, patients who haven’t met their deductible and normally would have to pay the full retail price for their insulin would pay $25. The same goes for those whose normal copayment is a percentage of that retail price. Miller says on average patients pay about $40 a month for insulin copayments — but the price can vary widely month to month, depending on the design of a patient’s prescription drug plan.

The announcement by Express Scripts, one of the biggest pharmacy benefit managers, comes a day after a subcommittee hearing in the House of Representatives that focused on the high costs of insulin.

Patient advocate Gail DeVore testified at the hearing.

“Every day I get emails from people asking, ‘How do I afford insulin?’ ” DeVore told the members of the Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations. “Every day. And every day I have to help them find a way to find insulin.”

DeVore, who has been dependent on insulin to control her diabetes for 47 years, says the full retail price for her insulin is $1,400 per month. She has good insurance, she says, so her cost for that drug is manageable. But her insurance doesn’t cover a second, fast-acting insulin she sometimes needs, so she says she dilutes it to make it last longer.

A recent study by researchers at Yale found that about a quarter of people with diabetes skip doses to save money or use less of the medication than prescribed.

“Patients who rationed insulin were more likely to have poor control of their blood sugars,” Dr. Kasia Lipska, an endocrinologist and assistant professor at Yale, testified at the hearing. She said patients who don’t maintain good control of their blood sugar run the risk of amputations, blindness and other diabetes complications.

Lipska told the lawmakers that drug companies are raising prices for no apparent reason. She urged the committee members to focus on the list prices of the drugs that pharmaceutical companies set rather than worrying about discounts and rebates.

“The bottom line is that drug prices are set by drugmakers,” she told lawmakers. “The list price for insulin has gone up dramatically — and that’s the price that many patients pay. This is what needs to come down. It’s as simple as that.”

Express Scripts’ program doesn’t do that, Miller acknowledges.

“This is not lowering the price of the drug,” Miller says. “We think there is a whole different issue, and that is, ‘What’s the price of pharmaceuticals in the United States?’ This does not address that. This truly is addressing the pain that patients are experiencing at the counter.”

Last month, Eli Lilly & Co. said it would begin selling an “authorized generic” version of one of its insulin products at half the retail price.

According to Express Scripts, its $25 copay deal will be available near the end of this year to patients who are not covered by a government insurance program (such as Medicare or Medicaid).

Congressional Panel: Consumers Shouldn’t Have To Solve Surprise Medical Bill Problem

Surprise bills happen when patients go to a hospital they think is in their insurance network but are seen by doctors or specialists who aren’t.

PeopleImages/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

PeopleImages/Getty Images

One point drew clear agreement Tuesday during a House subcommittee hearing: When it comes to the problem of surprise medical bills, the solution must protect patients — not demand that they be great negotiators.

“It is the providers and insurers, not patients, who should bear the burden of settling on a fair payment,” said Frederick Isasi, the executive director of Families USA. He was one of the witnesses who testified before the House Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions Subcommittee of the Education & Labor Committee.

Surprise, or “balance,” bills happen when patients go to a hospital they think is in their insurance network, but are then seen by a doctor or specialist who isn’t. The patient is then on the hook for an often very high bill — sometimes exceeding thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars.

Stories in the Bill of the Month series by NPR and Kaiser Health News have drawn attention to the problem.

Surprise billing is one of the rare public policy problems that are both bipartisan and in need of a federal solution. Around 60 percent of people are covered by employer-sponsored insurance, which is regulated by the federal government, and aren’t protected by the nearly two dozen state laws governing balance billing.

“We have people on this committee that have done yeoman efforts to come up with solutions in their own states,” said Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Mich., the panel’s ranking member. “I think we have a head start in understanding some of the pitfalls to stay away from and some of the benefits we can go directly toward.”

Several policy solutions have been introduced in Congress and discussed at the White House, but the witnesses testifying before the panel were firm that any answer needed to be worked out between key stakeholders — providers and insurers — instead of forcing consumers to file complaints and go through arbitration processes.

The problem, according to testimony, needs to be solved at the root. Instead of allowing a situation in which patients must negotiate a payment plan after receiving a surprise bill, hospitals and insurers need to remove the incentives for doctors to remain out of network.

Right now, if doctors opt out of an insurance network, they can charge prices that are “largely made up,” said Christen Linke Young, a fellow at USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy.

“We need to limit how much they can be paid in out-of-network scenarios to make it less attractive,” Young said.

Experts offered a few solutions, like capping how much providers can be paid if they are out of network. Ilyse Schuman, senior vice president of health policy at the American Benefits Council, suggested capping reimbursement for out-of-network emergency services at 125 percent of what the physician would get from Medicare.

Rep. Phil Roe, R-Tenn., an obstetrician, expressed concerns that tying payments to Medicare would disadvantage rural communities like his, where Medicare reimburses doctors less.

“We pay our providers less and can keep less than 10 percent of nurses we train in the area because we can’t pay them,” Roe said.

Rep. Susan Wild, a Pennsylvania Democrat, acknowledged that surprise billing is one problem that both parties are motivated to solve, but she was skeptical that a path forward was on the horizon. “The solutions I’m hearing don’t sound workable in the context of our present medical system,” Wild said.

“Isn’t the real problem the fact that we’ve turned over our medical system to private market forces?” she asked.

While price transparency is often touted as the antidote to high medical bills, panelists were adamant that more information alone is not enough to stop balance bills.

Patients usually can’t shop around for an anesthesiologist, for instance, no matter how much information they have.

“Notice isn’t enough here; even if the consumer has perfect information, they can’t do anything with that information,” Young testified. “They can’t go across town to get their anesthesia and go back to the hospital.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service and editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. You can follow Rachel Bluth onTwitter: @RachelHBluth