Oklahoma Attorney General On Purdue Pharma Settlement

NPR’s Rachel Martin speaks to Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter about his state’s settlement against Purdue Pharma, the maker of the powerful opioid OxyContin.

NPR’s Rachel Martin speaks to Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter about his state’s settlement against Purdue Pharma, the maker of the powerful opioid OxyContin.

Both Democrats and Republicans have introduced proposals that would impose a cap on out-of-pocket costs of prescription drugs for Medicare patients. But it’s still unclear whether those moves will gain a foothold.

Jeffrey Hamilton/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jeffrey Hamilton/Getty Images

Three times a week, 66-year-old Tod Gervich injects himself with Copaxone, a prescription drug that can reduce the frequency of relapses in people who have some forms of multiple sclerosis. After living with the disease for more than 20 years, the self-employed certified financial planner in Mashpee, Mass., is accustomed to managing his condition. What he can’t get used to is how Medicare’s coinsurance charges put a strain on his wallet.

Unlike commercial plans that cap members’ out-of-pocket drug spending annually, Medicare has no limit for prescription medications in Part D, its drug benefit. With the cost of specialty drugs increasing, some Medicare beneficiaries could owe thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket drug costs every year for a single drug.

Recent proposals by the Trump administration and Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., would address the long-standing problem by imposing a spending cap. But it’s unclear whether any of these proposals will gain a foothold.

The 2006 introduction of the Medicare prescription drug benefit was a boon for seniors, but the coverage had weak spots. One was the so-called doughnut hole — the gap beneficiaries fell into after they accumulated a few thousand dollars in drug expenses and were then on the hook for the full cost of their medications. Another was the lack of an annual cap on drug spending.

Legislative changes have gradually closed the doughnut hole so that this year beneficiaries no longer face a coverage gap. In a standard Medicare drug plan, beneficiaries pay 25 percent of the price of their brand-name drugs until they reach $5,100 in out-of-pocket costs. Once patients reach that threshold, the catastrophic portion of their coverage kicks in, and their obligation drops to 5 percent. But it never disappears.

It’s that ongoing 5 percent that hits hard for people, like Gervich, who take expensive medications.

His 40-milligram dose of Copaxone costs about $75,000 annually, according to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. In January, Gervich paid $1,800 for the drug, and he paid another $900 in February. Discounts that drug manufacturers are required to provide to Part D enrollees also counted toward his out-of-pocket costs. (More on that later.) By March, he had hit the $5,100 threshold that pushed him into catastrophic coverage. For the rest of the year, he’ll owe $295 a month for this drug, until the cycle starts over again in January.

That $295 is a far cry from the approximately $6,250 monthly Copaxone price without insurance. But, combined with the $2,700 he had already paid before his catastrophic coverage kicked in, the additional $2,950 he’ll owe this year is no small amount. And that assumes he needs no other medications.

“I feel like I’m being punished financially for having a chronic disease,” he says. He has considered discontinuing Copaxone to save money.

His drug bill is one reason Gervich has decided not to retire yet, he says, adding that an annual cap on his out-of-pocket costs “would definitely help.”

Drugs like Copaxone that can modify the effects of the disease have been on a steep upward price trajectory in recent years, says Bari Talente, executive vice president for advocacy at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Drugs that five years ago cost $60,000 annually now cost $90,000, she says. With those totals, Medicare beneficiaries “are going to hit catastrophic coverage no matter what.”

Specialty-tier drugs for multiple sclerosis, cancer and other conditions — defined by Medicare as those that cost more than $670 a month — account for more than 20 percent of total spending in Part D plans, up from about 6 percent before 2010, according to a report by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, a nonpartisan agency that advises Congress about the program.

Just over 1 million Medicare beneficiaries in Part D plans who did not receive low-income subsidies had drug costs that pushed them into catastrophic coverage in 2015 — more than twice the 2007 total — according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“When the drug benefit was created, 5 percent probably didn’t seem like that big a deal,” says Juliette Cubanski, associate director of the Program on Medicare Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “Now we have such expensive medications, and many of them are covered under Part D — where, before, many expensive drugs were cancer drugs” that were administered in doctors’ offices and covered by other parts of Medicare.

The lack of a spending limit for the Medicare drug benefit sets it apart from other coverage. Under the Affordable Care Act, the maximum amount someone generally owes out-of-pocket for covered drugs and other medical care for this year is $7,900. Plans typically pay 100 percent of customers’ costs after that.

The Medicare program doesn’t have an out-of-pocket spending limit for Part A or Part B, which cover hospital and outpatient services, respectively. But beneficiaries can buy supplemental Medigap plans, some of which pay coinsurance amounts and set out-of-pocket spending limits. Medigap plans, however, don’t cover Part D prescription plans.

Counterbalancing the administration’s proposal to impose a spending cap on prescription drugs is another proposal that could increase many beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket drug costs.

Currently, brand-name drugs that enrollees receive are discounted by 70 percent by manufacturers when Medicare beneficiaries have accumulated at least $3,820 in drug costs and until they reach $5,100 in out-of-pocket costs. Those discounts are applied toward beneficiaries’ total out-of-pocket costs, moving them more quickly toward catastrophic coverage.

Under the administration’s proposal, manufacturer discounts would no longer be treated this way. The administration says this would help steer patients toward less expensive generic medications.

Still, beneficiaries would have to pay more out-of-pocket to reach the catastrophic spending threshold. Thus, fewer people would likely reach the catastrophic coverage level at which they could benefit from a spending cap.

“Our concern is that some people will be paying more out-of-pocket to get to the $5,100 threshold and the drug cap,” says Keysha Brooks-Coley, vice president of federal affairs at the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network.

“It’s kind of a mixed bag,” says Cubanski of the proposed calculation change. “There will be savings for some individuals” who reach the catastrophic phase of coverage. “But for many, there will be higher costs.”

For some people, especially cancer patients taking chemotherapy pills, the lack of a drug-spending cap in Part D coverage can seem especially unjust.

These cutting-edge, targeted oral chemotherapy and other drugs tend to be expensive, and Medicare beneficiaries often hit the catastrophic threshold quickly, says Brooks-Coley.

Patty Armstrong-Bolle, a Medicare patient who lives in Haslett, Mich., takes Ibrance, a pill, once a day to help keep in check the breast cancer that has spread to other parts of her body. While the medicine has helped send her cancer into remission, she may never be free of a financial obligation for the pricey drug.

Armstrong-Bolle paid $2,200 for the drug in January and February of last year. When she entered the catastrophic coverage portion of her Part D plan, the cost dropped to $584 per month. Armstrong-Bolle’s husband died last year, and she used the money from his life insurance policy to cover her drug bills.

This year, a patient assistance program has covered the first few months of coinsurance. That money will run out next month, and she’ll owe her $584 portion again.

If she were getting traditional drug infusions instead of taking an oral medication, her treatment would be covered under Part B of the program, and her coinsurance payments could be covered.

“It just doesn’t seem fair,” she says.

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service, is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Neither KHN nor KFF is affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. Michelle Andrews is on Twitter: @mandrews110.

Advisers to the FDA concluded a meeting Tuesday on the safety of breast implants. What’s emerged is a lack of scientific certainty about the risks implants pose to millions of women who have them.

Purdue Pharma, the maker of opioid OxyContin, has reached a $270 million civil settlement with the state of Oklahoma.

The Trump administration’s shift in a major legal case against the Affordable Care Act could lead to the reversal of the expansive law and far-reaching effects on all Americans’ health care.

Contrast agent, a drug that enhances CT scans, is sometimes skipped because of concerns about side effects.

Morsa Images/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Morsa Images/Getty Images

One of the most widely used drugs in the world isn’t really a drug, at least not in the usual sense.

It’s more like a dye.

Physicians call this drug “contrast,” shorthand for contrast agent.

Contrast agents are chemical compounds that doctors use to improve the quality of an imaging test. In the emergency room, where I work, contrast is most commonly given intravenously during a CT scan.

About 80 million CT scans are performed annually in the U.S., and the majority are done with contrast.

Most contrast agents I use contain iodine, which can block X-rays. This effect causes parts of an image to light up, which significantly enhances doctors’ ability to detect things like tumors, certain kinds of infections and blood clots.

One thing about contrast agents that makes them different from typical drugs is that they have no direct therapeutic effect. They don’t make you feel better or treat what’s ailing you. But they might be crucial in helping your doctor make the right diagnosis.

Because these drugs are used in some people who might not turn out to have anything wrong with them, and in others who may be seriously ill, contrast agents need to be quite safe.

And by and large they are. Some patients may develop serious allergic reactions or cardiovascular complications, but these are rare. Others may experience nausea or headache.

But there is one widely feared adverse effect of contrast — kidney damage. As a result, contrast is often withheld from patients deemed by their doctors to be at risk for kidney problems. The downside is that these patients may not receive the diagnostic information that would be most useful for them.

In recent years, though, new research has led some physicians to question whether this effect has been overstated.

Is it time to rethink the risk?

The first report of kidney damage after intravenous contrast, which became known as contrast-induced nephropathy, or CIN, appeared in a Scandinavian medical journal in 1954. An early form of contrast had been given to a patient for a diagnostic test. The patient quickly developed renal failure and died. The authors proposed that the contrast may have been responsible, because they could find no other clear cause during an autopsy.

With other physicians now primed to the possibility, similar reports began appearing. By the 1970s, renal injury had become a “well-known complication” of contrast in patients with risk factors for kidney disease, like diabetes. By 1987, intravenous contrast was proclaimed to be the third-leading cause of hospital-acquired kidney failure.

The belief that contrast agents were risky had a significant effect on how often doctors used them. In a 1999 survey of European radiologists, 100 percent of respondents believed that CIN occurred in at least 10-20 percent of at-risk patients, and nearly 20 percent believed it occurred in over 30 percent of such patients. A 2006 survey found that 94 percent of radiologists considered contrast to be contraindicated beyond a certain threshold of renal function — a threshold that nearly 1 in 10 middle-aged American men could exceed.

But Dr. Jeffrey Newhouse, a professor of radiology at Columbia University, had a hunch that something wasn’t quite right with the conventional wisdom. He has administered contrast thousands of times, and rarely did it seem to him that contrast could be said to have been directly toxic. There were often far too many variables at play.

Newhouse decided to go back to the primary literature. In 2006, he and a colleague reviewed more than 3,000 studies on contrast-induced nephropathy and came to an astounding conclusion — only two had used control groups, and neither of those had found that contrast was dangerous.

“Everyone assumed that any kidney injury after contrast was a result of the contrast,” Newhouse said, “but these studies had no control groups!”

In other words, there was no group of patients who hadn’t received contrast to use for comparison.

Newhouse discovered that nearly every study supporting CIN had fallen prey to this shortcoming. The importance of controls in any experiment is elementary-level science; without them, you can’t say anything about causation.

What came next was brilliant. “Having criticized those that did the experiment without the control, we decided to do the control without the experiment,” Newhouse said. He reviewed 10 years of data from 32,000 hospitalized patients, none of whom received contrast. He found that more than half of the patients had fluctuations in their renal function that would have met criteria for CIN had they received contrast.

This raised the possibility that other causes of kidney injury — and not the contrast — could have explained the association found in earlier studies.

Other researchers stepped up after Newhouse published his findings in 2008. Physicians in Wisconsin conducted the first large study of CIN with a control group in 2009. In more than 11,500 patients, overall rates of kidney injury were similar between people who received contrast and those who hadn’t.

There was one major weakness with the study, though — it was retrospective, meaning it relied on medical records and previously collected data. When a study is performed this way, randomization to different treatments can’t be used to guard against biases that could distort results.

So, for instance, if the physicians treating patients in the Wisconsin study were worried about giving contrast to high-risk patients, they may have steered them into the group receiving CT scans without it. These sicker patients might have been more likely to have kidney injury from other causes, which could mask a true difference between the groups.

The next generation of retrospective studies tried to use a special statistical technique to control for these biases.

The first two appeared in 2013. Researchers in Michigan found that contrast was associated with kidney injury in only the highest-risk patients, while counterparts at the Mayo Clinic, using slightly more sophisticated methods, found no association between contrast and kidney injury.

A third study, from Johns Hopkins, appeared in 2017. It, too, found no relationship between contrast and kidney injury in nearly 18,000 patients. And in 2018, a meta-analysis of more than 100,000 patients also found no association.

What did Newhouse make of these results?

“Nearly harmless and totally harmless — we’re somewhere between those two,” he says. “But how much harm is done in withholding the stuff? We just don’t know.”

Still, Dr. Michael Rudnick, a kidney specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, isn’t so sure it’s time to clear contrast agents completely. He thinks there still could be some danger to the highest-risk patients, as the Michigan researchers found. And he pointed out that even sophisticated statistical analyses can’t control for all possible biases. Only a randomized trial can do that.

Here’s the rub, though. Rudnick says we’re unlikely to get a randomized, controlled trial because there’s still a possibility that contrast could be harmful, and ethics committees are unlikely to approve such a trial.

It’s a conundrum that existing belief about contrast agents could actually limit our ability to conduct the appropriate trials to investigate that belief.

Matthew Davenport, lead author of the 2013 Michigan study, and chair of the American College of Radiology’s Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media, says “the vast majority of things we used to think were CIN probably weren’t.”

But he does agree with Rudnick that there could still be real danger for the highest-risk patients. He echoed the current American College of Radiology recommendations that the decision to use contrast in patients with pre-existing renal disease should remain an individualized clinical decision.

For now, if you are in need of a scan that could require contrast, talk about the risks and benefits of the medicine for you and make the decision together with your doctor.

Clayton Dalton is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology says suggestions that a medical abortion can be reversed after more than an hour has passed aren’t supported by scientific evidence.

Roy Scott/Ikon Images/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Roy Scott/Ikon Images/Getty Images

Dr. Mitchell Creinin never expected to be in the position of investigating a treatment he doesn’t think works.

And yet, Creinin will be spending the next year or so using a research grant from the Society of Family Planning to put to the test a treatment he sees as dubious — one that recently has gained traction, mostly via the Internet, among groups that oppose abortion. They call it “abortion pill reversal.”

The technique — a series of oral or injected doses of the hormone progesterone given over the course of several days — arose outside the usual avenues of scientific testing, says Creinin, a medical researcher and professor at the University of California, Davis.

Creinin, an OB-GYN, has spent the bulk of his career in family planning research. He has studied topics ranging from different treatments for miscarriage to how women choose birth control methods.

Performing abortions, he says, has always been a part of his practice and philosophy. “I need to provide these services to help women,” Creinin says.

Proponents of “abortion pill reversal” say it can stop a medication-based abortion in the first trimester, if the progesterone is administered in time.

But Creinin says the progesterone treatments are ineffective at best in halting an abortion that has already begun. And, Creinin says, promotion of the treatment can be potentially harmful by giving pregnant women misleading information that an abortion can be undone.

Though critics of abortion pill reversal say the term is an unproven misnomer, it has been such a compelling phrase that it’s already been written into the laws of a number of states.

Legislators in Arkansas, Idaho, South Dakota and Utah have made it a legal requirement in recent years that doctors who provide medical abortions must tell their patients that “reversal” is an option, although they are not prevented from also telling patients if they think the treatment doesn’t work.

Medical researchers such as Creinin and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are concerned by that trend.

“You create a law based on no science — absolutely zero science,” Creinin says.

Proponents of the technique say they do have evidence. But it’s anecdotal, Creinin says, or comes from studies that lack rigorous controls. It’s time, Creinin says, for a formal study that can be definitive.

“I want to own that,” he says.

Abortion choices

In the first 10 weeks of a pregnancy, women who are seeking abortions generally have two options: a surgical procedure or a medication-based abortion (after that, only surgical abortions are performed).

The medication-based regimen uses a combination of two medicines — mifepristone and misoprostol — which women usually take 24 hours apart.

Mifepristone pills work by blocking progesterone, a hormone that helps maintain a pregnancy. The second medicine, misoprostol, makes the uterus contract, to complete the abortion. Studies suggest that 95 percent to 98 percent of women who take both drugs in the prescribed regimen will end the pregnancy without harm to the woman. Surgical evacuation can complete the abortion, if necessary.

So what happens if a woman takes mifepristone, then changes her mind and wants to continue with the pregnancy?

If the change of heart comes in the first hour after she’s swallowed that initial medicine, her doctor might help her induce vomiting. If she hasn’t yet absorbed the first drug, the process may be stopped before it starts.

The bigger question, and one for which the data are murkier, is: What happens if a woman takes the first medicine but never goes on to take misoprostol, the second drug in the regimen?

According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “as many as half of women who take only mifepristone continue their pregnancies.” (If the pregnancy does continue, mifepristone isn’t known to cause birth defects, ACOG notes.)

In 2012, a San Diego physician named George Delgado said he had hit upon a chemical way of stopping the abortion process with more certainty — a way to give more control to a woman who changed her mind. He called his protocol “abortion pill reversal.”

A family medicine physician, Delgado calls himself “pro-life,” not anti-abortion. He says about a decade ago he got interested in the 24-hour window after a woman takes mifepristone but before she takes misoprostol.

He’d received a call from a local activist who said a woman needed Delgado’s help. She had swallowed the first pill in the abortion regimen but had reconsidered and no longer wanted to end her pregnancy.

“People do change their minds all the time,” Delgado says.

Hoping to help the woman, Delgado gave her progesterone — a medication that has many uses, including as a treatment for irregular vaginal bleeding and as part of hormone replacement therapy during menopause. If progesterone is useful in these other ways, Delgado figured, it might stop the action of the progesterone-blocker mifepristone, and halt an abortion.

Delgado says the pregnancy of that first patient continued uneventfully, which he credits to the progesterone.

He then started giving the progesterone treatment to more patients who came to him. He went on to develop a network of clinicians around the country willing to give progesterone to patients who no longer want to go through with their abortions, although he wouldn’t say how many of those clinicians took part in his research.

These days, Delgado says, most women who come to him for the progesterone treatment are self-referrals. While searching online, many find the website for the Abortion Pill Rescue Network, a nationwide group of clinicians who provide the treatment.

The network is backed by Heartbeat International, an anti-abortion rights group, and, according to spokesperson Andrea Trudden, includes more than 500 clinicians willing to prescribe progesterone to patients who have initiated the medication abortion process.

In support of their claims about abortion pill reversal, Delgado and colleagues have published their research in medical journals.

In 2012, Delgado co-authored a report in the Annals of Pharmacotherapy on the experiences of six pregnant women who received mifepristone and then injections of progesterone. Four of the women, the paper said, were able to carry their pregnancies to term.

In a statement released in August 2017, ACOG said the results of the study, a type known as a case series that didn’t include a comparison group, “is not scientific evidence that progesterone resulted in the continuation of those pregnancies.” ACOG’s statement also said: “Case series with no control group are among the weakest forms of medical evidence.”

In 2018, Delgado and colleagues in his network of health providers published a larger case series, this one involving 754 patients, in the journal Issues in Law and Medicine. The paper concluded that the reversal of mifepristone’s effects with progesterone “is safe and effective.”

The researchers acknowledged that the study didn’t randomly assign women to receive a placebo or mifepristone. A study like that, called a randomized placebo-controlled trial, would provide strong evidence. But Delgado and his colleagues wrote that doing this kind of trial “in women who regret their abortion and want to save the pregnancy would be unethical.”

“There’s no alternative treatment,” he says. “You can’t always wait for the [randomized, controlled trials]. If it’s lifesaving, there’s no alternative.”

State legislatures consider “abortion reversal” bills

One of Delgado’s most outspoken critics, Dr. Daniel Grossman, an OB-GYN at the University of California, San Francisco, says all of the published studies supporting this use of progesterone have been marred by methodological flaws that inflate the “success rate” of the reversal treatment.

Last October, Grossman and Kari White, a sociologist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham who studies family planning issues, wrote an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine criticizing Delgado’s research methodology, saying he used flawed statistics and didn’t set rigorous criteria for the characteristics patients had to fulfill to be included in the study.

“A systematic review we coauthored in 2015 found no evidence that pregnancy continuation was more likely after treatment with progesterone as compared with expectant management among women who had taken mifepristone,” they wrote.

“I think there’s a big bias against abortion pill reversal,” Delgado says in response. “ACOG typifies that bias by coming out with strong statements. … This is a new science, but we have a substantial amount of data, and it’s been proven to be safe.”

The critics haven’t slowed Delgado’s supporters.

Already in 2019, legislators in several states — Kansas, Kentucky, North Dakota and Nebraska — have been considering bills that would require abortion providers to tell their patients about abortion reversal. Back in 2017, Delgado testified in support of similar legislation in Colorado, although the proposal never made it into law.

Grossman says he’s furious that states are forcing abortion providers to give their patients inaccurate information related to abortion care.

What’s more, Grossman says, “these laws take an extra step … and essentially are encouraging patients to be a part of clinical research that isn’t really being appropriately monitored. … This is really an experimental treatment.”

Progesterone hasn’t been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration for reversing a medication abortion. Doctors are permitted to prescribe drugs for uses not approved by the FDA as part of the practice of medicine. It’s known as off-label use.

Until Delgado published his 2018 paper, Delgado told his patients they were receiving a “novel treatment.” He says he believes there is now enough research to support the routine off-label prescription of progesterone for women who don’t want to complete a medication-based abortion.

“Now we have a substantial amount of data. There is no alternative. And it’s been proven to be safe,” Delgado says. “Why not give it a chance?”

Although Creinin disagrees that the evidence supports this use of progesterone, he is sympathetic to the idea that women who seek an abortion may not be certain about the decision at their first appointment. Creinin says he supports policies that allow women as much control as possible over the decision about whether or not to terminate a pregnancy.

“There are people who change their minds,” Creinin says. “That’s a normal part of human nature.”

UCSF’s Grossman agrees.

He encourages abortion providers, when possible, to send the mifepristone and misoprostol home with the patient, if she requests it. That way, she can start the protocol only if and when she’s ready, rather than make the decision in a clinic where she might feel rushed. (FDA rules about mifepristone say the pill can only be dispensed in certain types of clinics — usually clinics that provide abortions. And some states have additional restrictions on how and where the drugs can be prescribed and taken.)

Putting abortion reversal to the test

Creinin’s study, approved by the UC Davis institutional review board in December, has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, which tracks medical research.

The study is slated to involve 40 women who are between 44 and 63 days of pregnancy and are seeking to have a surgical abortion. As a condition of the research, the women would have to be willing to take mifepristone, the initial pill that would normally trigger a medical abortion, and then a placebo or progesterone.

Two weeks later, researchers will see if there’s any difference in the rates of continued pregnancy. If progesterone can prevent the effects of mifepristone, Creinin says, he’ll find that more women in the group that got progesterone are still pregnant, with a pregnancy that’s progressing.

The key ethical point, the researchers say, is that all the women in this study want to have an abortion and will get one by the study’s end. The study isn’t enrolling women who are seeking a “reversal.” They will be told upfront that if the mifepristone doesn’t prompt an abortion, they will be offered a surgical abortion.

Creinin says the study participants will be compensated for their time in the study, but won’t be paid for having an abortion. And patients will still be responsible for the cost of the surgical procedure — either through their insurance or out-of-pocket.

Creinin is skeptical that progesterone will have any effect, since it is thought that mifepristone irreversibly blocks progesterone in the body.

But if it does have a clinically significant effect, he says, “I want to know that.”

Creinin hopes that his work will help medical researchers better understand if this kind of treatment can actually help women who change their minds after taking mifepristone for a medication abortion.

If the results show the progesterone doesn’t work, Creinin hopes that it will discourage state legislators from mandating that doctors tell their patients about an ineffective treatment.

Creinin started enrolling patients in the study in February. He isn’t sure how long the study will take, but says he probably won’t have preliminary results for at least a year.

Dr. Mara Gordon is the NPR Health and Media Fellow from the Department of Family Medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

One of the Trump administration’s proposals would change the prices Medicare pays for certain prescription drugs by factoring in the average prices Europeans pay for the same medicines.

Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images

A new drug to treat postpartum depression is likely to reach the U.S. market in June, with a $34,000 price tag. The approval of the drug by the Food and Drug Administration comes on the heels of another approval, just two weeks ago, of a different antidepressant, whose retail price will be as much as $6,700 a month.

Those giant list prices send shivers through the insurance industry and across the federal government and state governments, which pay for about 40 percent of prescription drugs sold in the United States.

The Trump administration is working to bring those prices down. The Department of Health and Human Services in recent months has proposed a series of regulations aimed at reshaping the prescription drug market. The goal, administration officials say, is to create more competition and lower costs.

But economists and analysts, who applaud the efforts to bring clarity to what is now a murky pricing system, doubt the effort will actually cut total spending on prescription drugs.

“They’re trying to … improve the function of the market,” says Sara Fisher Ellison, a health economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “But, to be honest, they probably missed the mark.”

The biggest change proposed by HHS Secretary Alex Azar would upend the entire system that sets the prices for medications that people buy at their local pharmacies.

Today those prices are negotiated in secret, as rebates between drug companies and middlemen known as pharmacy benefit managers. The PBMs often keep a share of the rebates for themselves, and when consumers have to pay for their medications, to meet a deductible for example, they have to pay that full pre-rebate price.

Azar says his plan would “replace today’s opaque system of rebates, which drives prices higher and higher, with a system of transparent and upfront discounts delivered directly to patients that will finally drive prices down.”

Those discounts would no longer be secret, and consumers who have to pay for some drugs would pay that discounted price.

The plan would not only help consumers at the pharmacy counter, Azar says, but also motivate drugmakers to lower their inflated list prices. HHS is accepting public comments on this proposed rule until April 8.

The change is revolutionary, says Dr. Walid Gellad, director of the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh.

“The competition between companies has been on how big a rebate they can give,” Gellad says, “and the way that you give a big rebate is by increasing the list price. So the idea is to get rid of that so that companies can compete based on getting the list price lower.”

But Len Nichols, an economist and the director of the Center for Health Policy Research and Ethics at George Mason University, doubts that the changes will end with overall prices being lower than the deals that pharmacy benefit managers get today.

“The truth is [the PBMs] still, on balance, lower prices from what they would be if they didn’t exist,” Nichols says. “Which is exactly why we need them.”

The drug market is not like a normal retail market, Nichols says, because it’s dominated by a few powerful companies — the PBMs — that are practically required to buy almost all the products offered by the drug companies.

In that type of system, price transparency can lead to higher prices, Nichols and other economists say.

“One way to think about it is … imagine if what you wanted was for a cartel to work perfectly,” he says. “One way a cartel works perfectly is if all members of the cartel know everybody else’s price.”

In October, Azar also proposed requiring drug companies to include the list prices of their medications in television and magazine ads — that proposal is still pending. Drugmakers oppose that requirement because, they say, those list prices are irrelevant precisely because of the rebate system. Nobody pays the actual list price, they argue.

But there is some evidence that drug companies don’t want the huge price tags they put on their products to be widely publicized. That “naming and shaming” of companies can have an impact on their behavior, says MIT’s Fisher Ellison.

Still, she says, while the focus on publicizing prices for consumers seems like it should work, it may not have much effect on overall spending.

That’s because consumers not only don’t pay list prices but also don’t really choose which medication they’re buying. That decision is in the hands of their doctor. And, unlike with toothpaste or soda, it’s not easy for a consumer to switch brands of medicine.

“You can imagine a patient walking into a pharmacy, and he has a prescription for Lipitor and then finds out that Zocor, which is a similar drug, is a lot cheaper. Well, there’s nothing he can do at that point,” Ellison says.

When it comes to driving down prices, analysts say HHS’s third proposal is likely to work. That plan would tie the price that Medicare pays for drugs that are administered in a hospital or clinic — such as IV drugs for cancer or arthritis — to the prices paid in other countries.

That proposed rule — which has received more than 2,700 public comments — is facing steep opposition from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has been running an aggressive campaign against the proposal. It’s unclear when the proposal might be finalized.

And doctors who administer the drugs are also opposed, saying it may hurt patients’ access to medications.

“I’ve basically traveled the world … looking at cancer care,” says Ted Okun, the executive director of the Community Oncology Alliance, “and other countries do not have the access to the drugs that we have here.”

But Azar dismisses that argument. He says the U.S. price for a drug will still be higher than prices paid elsewhere and says he doubts any companies will stop selling their products in the huge U.S. market just because prices are lower than they are today.

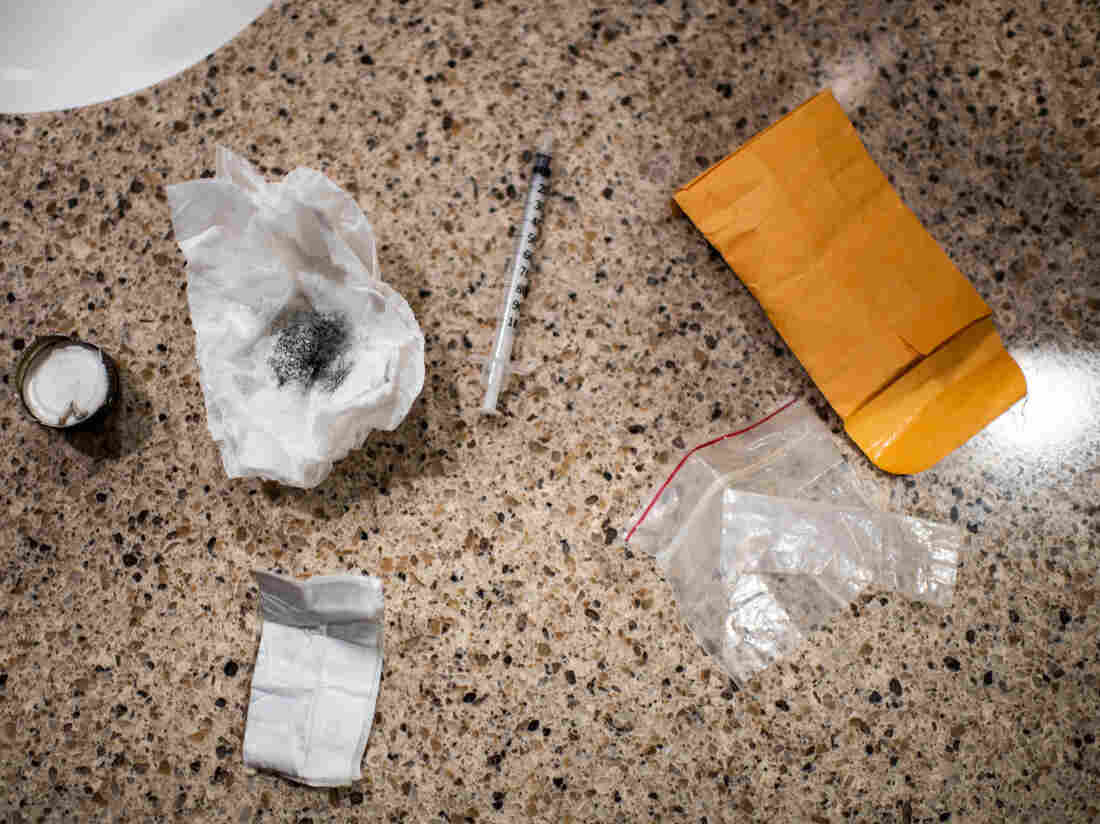

Authorities intercepted a woman using this drug kit in preparation for shooting up a mix of heroin and fentanyl inside a Walmart bathroom last month in Manchester, N.H. Fentanyl offers a particularly potent high but also can shut down breathing in under a minute.

Salwan Georges/Washington Post/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Salwan Georges/Washington Post/Getty Images

Men are dying after opioid overdoses at nearly three times the rate of women in the United States. Overdose deaths are increasing faster among black and Latino Americans than among whites. And there’s an especially steep rise in the number of young adults ages 25 to 34 whose death certificates include some version of the drug fentanyl.

These findings, published Thursday in a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, highlight the start of the third wave of the nation’s opioid epidemic. The first was prescription pain medications, such as OxyContin; then heroin, which replaced pills when they became too expensive; and now fentanyl.

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that can shut down breathing in less than a minute, and its popularity in the U.S. began to surge at the end of 2013. For each of the next three years, fatal overdoses involving fentanyl doubled, “rising at an exponential rate,” says Merianne Rose Spencer, a statistician at the CDC and one of the study’s authors.

Spencer’s research shows a 113 percent average annual increase from 2013 to 2016 (when adjusted for age). That total was first reported late in 2018, but Spencer looked deeper with this report into the demographic characteristics of those people dying from fentanyl overdoses.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

Increased trafficking of the drug and increased use are both fueling the spike in fentanyl deaths. For drug dealers, fentanyl is easier to produce than some other opioids. Unlike the poppies needed for heroin, which can be spoiled by weather or a bad harvest, fentanyl’s ingredients are easily supplied; it’s a synthetic combination of chemicals, often produced in China and packaged in Mexico, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. And because fentanyl can be 50 times more powerful than heroin, smaller amounts translate to bigger profits.

Jon DeLena, assistant special agent in charge of the DEA’s New England Field Division, says one kilogram of fentanyl, driven across the southern U.S. border, can be mixed with fillers or other drugs to create six or eight kilograms for sale.

“I mean, imagine that business model,” DeLena says. “If you went to any small-business owner and said, ‘Hey, I have a way to make your product eight times the product that you have now,’ there’s a tremendous windfall in there.”

For drug users, fentanyl is more likely to cause an overdose than heroin because it is so potent and because the high fades more quickly than with heroin. Drug users say they inject more frequently with fentanyl because the high doesn’t last as long — and more frequent injecting adds to their risk of overdose.

Fentanyl is also showing up in some supplies of cocaine and methamphetamines, which means that some people who don’t even know they need to worry about a fentanyl overdose are dying.

There are several ways fentanyl can wind up in a dose of some other drug. The mixing may be intentional, as a person seeks a more intense or different kind of high. It may happen as an accidental contamination, as dealers package their fentanyl and other drugs in the same place.

Or dealers may be adding fentanyl to cocaine and meth on purpose, in an effort to expand their clientele of users hooked on fentanyl.

“That’s something we have to consider,” says David Kelley, referring to the intentional addition of fentanyl to cocaine, heroin or other drugs by dealers. Kelley is deputy director of the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. “The fact that we’ve had instances where it’s been present with different drugs leads one to believe that could be a possibility.”

The picture gets more complicated, says Kelley, as dealers develop new forms of fentanyl that are even more deadly. The new CDC report shows dozens of varieties of the drug now on the streets.

The highest rates of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths were found in New England, according to the study, followed by states in the Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest. But fentanyl deaths had barely increased in the West — including in Hawaii and Alaska — as of the end of 2016.

Researchers have no firm explanations for these geographic differences, but some people watching the trends have theories. One is that it’s easier to mix a few white fentanyl crystals into the powdered form of heroin that is more common in eastern states than into the black tar heroin that is sold more routinely in the West. Another hypothesis holds that drug cartels used New England as a test market for fentanyl because the region has a strong, long-standing market for opioids.

Spencer, the study’s main author, hopes that some of the other characteristics of the wave of fentanyl highlighted in this report will help shape the public response. Why, for example, did the influx of fentanyl increase the overdose death rate among men to nearly three times the rate of overdose deaths among women?

Some research points to one particular factor: Men are more likely to use drugs alone. In the era of fentanyl, that increases a man’s chances of an overdose and death, says Ricky Bluthenthal, a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“You have stigma around your drug use, so you hide it,” Bluthenthal says. “You use by yourself in an unsupervised setting. [If] there’s fentanyl in it, then you die.”

Traci Green, deputy director of Boston Medical Center’s Injury Prevention Center, offers some other reasons. Women are more likely to buy and use drugs with a partner, Green says. And women are more likely to call for help — including 911 — and to seek help, including treatment.

“Women go to the doctor more,” she says. “We have health issues that take us to the doctor more. So we have more opportunities to help.”

Green notes that every interaction with a health care provider is a chance to bring someone into treatment. So this finding should encourage more outreach, she says, and encourage health care providers to find more ways to connect with active drug users.

As to why fentanyl seems to be hitting blacks and Latinos disproportionately as compared with whites, Green mentions the higher incarceration rates for blacks and Latinos. Those who formerly used opioids heavily face a particularly high risk of overdose when they leave jail or prison and inject fentanyl, she notes; they’ve lost their tolerance to high levels of the drugs.

There are also reports that African-Americans and Latinos are less likely to call 911 because they don’t trust first responders, and medication-based treatment may not be as available to racial minorities. Many Latinos say bilingual treatment programs are hard to find.

Spencer says the deaths attributed to fentanyl in her study should be seen as a minimum number — there are likely more that weren’t counted. Coroners in some states don’t test for the drug or don’t have equipment that can detect one of the dozens of new variations of fentanyl that would appear if sophisticated tests were more widely available.

There are signs the fentanyl surge continues. Kelley, with the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, notes that fentanyl seizures are rising. And in Massachusetts, one of the hardest-hit areas, state data show fentanyl present in more than 89 percent of fatal overdoses through October 2018.

Still, in one glimmer of hope, even as the number of overdoses in Massachusetts continues to rise, associated deaths dropped 4 percent last year. Many public health specialists attribute the decrease in deaths to the spreading availability of naloxone, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WBUR and Kaiser Health News.

The first drug for severe postpartum depression has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Thousands of women could benefit from the drug, but there are drawbacks, including a $35,000 price tag.