When Countries Get Wealthier, Kids Can Lose Out On Vaccines

Mothers and their babies in Nigeria wait at a health center that provides vaccinations against polio. Vaccination rates lag in the middle-income country.

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

You’d think that as a poor country grows wealthier, more of its children would get vaccinated for preventable diseases such as polio, measles and pneumonia.

But a review published in Nature this month offers a different perspective.

“The countries that are really poor get a lot of support for the vaccinations. The countries that are really rich can afford to pay for the vaccines anyway,” says Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of the review.

But, she says, “the middle-income countries are in a tricky situation because they don’t qualify for support, yet they don’t necessarily have the financial resources and stability to purchase the vaccines.”

Adrien de Chaisemartin, director of strategy and performance at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, agrees: “More and more vulnerable populations live in middle-income countries.” Gavi, an international nonprofit that helps buy and distribute vaccines, projects that 70% of the world’s under-immunized children will live in middle-income countries by 2030.

Brazil, India, Indonesia and Nigeria were among the 10 countries with the most children who lacked basic vaccinations in 2018 — for example, shots to prevent diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis by age 1. Each of those countries meets the World Bank’s definition of a middle-income country: an average annual income (known as the gross national income, or GNI, per capita) between $1,026 and $12,375. In Nigeria alone, 3 million kids are undervaccinated. That’s 15% of the world’s total of children who lack key vaccinations.

By contrast, vaccination rates can be high in poor countries, according to global health researchers, who say that Gavi has boosted the numbers. Rwanda, for instance, despite having a GNI of $780 per person, now has a near-universal coverage rate for childhood vaccines, on par with some of the wealthiest countries.

But in general, once a country reaches a GNI per capita threshold over $1,580 for three years, support from Gavi tapers off. And despite their improved fortunes, countries don’t always choose to fund childhood vaccines.

Angola is among the middle-income countries with the lowest vaccination rates. Diamonds and oil have helped propel the country out of low-income status, and its president is a billionaire. Yet an estimated 30% to 40% of children there did not receive basic vaccines in 2018.

The lag in vaccination rates is caused by any number of reasons. “There’s a whole list of middle-income countries, and they’re not all the same,” says Kampmann.

For example, Sam Agbo, former chief of child survival and development for UNICEF Angola, says Angola’s leadership does not fully fund immunization programs. Agbo blames a political system that he says is mired in corruption, financial mismanagement and lots of debt. So it’s hard to increase the health care budget. “Primary health care is not sexy,” he says. “People are interested in building hospitals and specialized centers rather than investing in preventive care.”

Gavi’s de Chaisemartin groups Angola with other resource-rich but corruption-plagued countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea and East Timor. “These are countries where the GNI is relatively high because of their oil resources, for the most part, but that doesn’t translate into a stronger health system,” says de Chaisemartin.

Then there’s the matter of cost. Countries that buy vaccines on the open market might pay over $100 a shot.

Public attitudes also play a role. In Brazil, which is on the high end of the middle-income spectrum, an immunization program that once outperformed World Health Organization recommendations has been declining for three years. Jorge Kalil Filho, an immunology professor at the University of Sao Paulo, says public inattention and anti-vaccine campaigns, popular on social media, are undermining progress.

De Chaisemartin says the global health community needs to adjust to an unprecedented global economic shift. “Fifteen years ago, the world was divided between poor countries, where most poor people were living, and high-income countries,” says de Chaisemartin. “Now you have a lot of middle-income countries with very poor and vulnerable populations.”

Opioid Addiction In Jails: An Anthropologist’s Perspective

A new book by anthropologist and physician Kimberly Sue tells the stories of women navigating opioid addiction during and after incarceration.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Dr. Kimberly Sue is the medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, a national advocacy group that works to change U.S. policies and attitudes about the treatment of drug users. She’s also a Harvard-trained anthropologist and a physician at the Rikers Island jail system in New York.

Sue thinks it’s a huge mistake to put people with drug use disorder behind bars.

“Incarceration is not an effective social policy,” she says. “It’s not an evidence-based policy. It’s not effective in deterring crime. But we continue to rely on it for reasons that have to do with morality.”

While a quarter or more of the U.S. prison population has an addiction to opioids, only 5% of those individuals receive medication for their chronic condition, Sue notes, despite the growing agreement among doctors that this approach to treatment saves lives.

In addition to her Rikers Island work with incarcerated women, Dr. Kimberly Sue is medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, an advocacy group that works to change U.S. policies and attitudes toward syringe exchanges and other evidence-based approaches to treating drug addiction.

Van Asher

hide caption

toggle caption

Van Asher

Statistics suggest that women might benefit most from improvements in treatment, she says. The rate of death from prescription opioid overdose has gone up nearly 500% among women since 1999, compared with 200% among men. And in recent decades, women’s rate of incarceration has grown at twice the rate of men’s.

We spoke with Sue about her new book, Getting Wrecked: Women, Incarceration, and the American Opioid Crisis, which is based on firsthand accounts from female inmates she has treated.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What are some of the arguments that jail is not the best public health solution to opioid use?

Incarceration in many cases harms people. We know that, for example, having been in solitary confinement increases your risk of death after release — like in the case of Kalief Browder, a young Bronx man who killed himself after three years at Rikers.

And the rate of opioid overdose in the first two weeks after people leave prison and jail is between 30 and 120 times higher than the general population.

In most of the county-level jails in this country, people are forced to withdraw off lifesaving, stabilizing medications [like methadone] against their will. Methadone is a treatment for opioid use disorder that you cannot access in jails in many places in this country.

There are documented cases of suicide around the country — including in my book — of people who are going through withdrawal in jails and either committing suicide or dying as a combination of medical neglect and loss of body fluids related to dehydration.

Can you describe that example from your book?

One of the women I took care of and interviewed at MCI-Framingham, a women’s state prison in Massachusetts, was in the health services unit — where they send people when they’re first coming in — and she heard someone withdrawing from methadone. That person was screaming — she was, you know, in agony. And then [my patient] stopped hearing her screaming. [My patient and other prisoners] tried to get the guards’ attention. And they found out that she had hung herself.

People going through withdrawal in jail health facilities — it’s not the same as being an inpatient in my hospital, with nurses monitoring you and someone with medical training taking care of you. These are cinder block cells where people are going through diarrhea, vomiting, sweats, muscle aches. And many jails around the country are getting lawsuits that are being settled for situations like this.

People in the commercial jail and prison system believe that what they do is the best way, but it’s not the equivalent of the standard of care that we offer in the community.

How do jails and prisons explain not having methadone available, if that endangers lives?

And liquid methadone costs pennies. It’s not a matter of cost — it’s a matter of political will.

The way I like to describe it is, if your brother had a heart attack and then became incarcerated, we would continue all six of the lifesaving medications he was prescribed, no matter what the cost — even hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. But if he had an opioid overdose and became incarcerated, they’d just stop the medication he was prescribed for opioid use disorder — they just wouldn’t give it to him.

In no other chronic health condition do we discriminate like this. There’s such a stigma that’s encoded into our policies.

You write about that in your book: “The crisis we face is not opioids. The crisis we face is a war on people who use drugs, and on our reliance on incarceration as a catch-all policy solution.”

Yes. And it’s not just opioids. As a doctor who takes care of people who use drugs, I don’t have a problem with people who use drugs. But there are so many people in this country who really hate them and don’t care if they die. Or don’t care if they are able to have lives of dignity and respect.

Is that because of stigma getting in the way? The idea that if you do drugs, you deserve whatever happens to you?

Yeah. The idea that substance use is a disease of the will is very heavily entrenched in American ideology. We have a hatred of people who are dependent on anything — including the government — for support. The idea of people being on welfare, the idea of people not working. We have these very strong puritanical roots and the idea that we make our bed, we lie in it, and you pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. It pits people against each other in a way.

People who use drugs — they have a physical dependence on a substance. It doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re bad people, but our society tells them that they’re bad people.

Notice that I don’t call substance use disorder a disease. It’s really much more complex than that. I don’t want it to be all medicalized, because so much of the answer is not in medicine. If you think about getting addicted to heroin or pills in West Virginia, a lot of it might have to do with poverty. As a doctor, so much of what I’d like to be able to do for you is to give you a job, you know? To give you an education and more opportunities. I’d like to give you a prescription for housing.

How does all this more specifically impact women?

For as long as we’ve been a country, women have been criminalized — not only for substance use, but for disorderly housekeeping, for leaving marriages, for abortion, for lewd behavior. Women have been criminalized basically for being seen as deviating from a certain upper-middle-class white morality.

Because women have the potential to be pregnant or are often mothers, there’s this added moralizing directed at women who use drugs. There have been laws, for example, that send women to jail for twice as long as they would sentence men for drinking in public, because of the idea that women had farther to fall.

Some of the women in my book were low-level drug dealers. And they didn’t have anything to give prosecutors, so they would get thrown under the bus by the men who were much higher up who had more information. So they would take the rap.

The rate of incarceration of women is still relatively small compared to that of men, but it’s gone up 840% over the past 40 years.

Other countries don’t do this. Portugal is held up as one of those models.

What is different in Portugal?

Portugal has decriminalized drug use. So if someone has problematic substance use, they don’t go to prison or jail for that.

So, is there no stigma associated with drug use there?

I just listened to a podcast episode by this guy who went around Portugal and asked people, “How does your society feel about people who use drugs?” And the people he interviewed were like, “They’re just people struggling. It’s not their problem — it’s a social problem.”

Basically, substance use is treated like a social condition, and all of the services that an individual would need get wrapped around it. They have mobile vans to bring methadone to where you’re living. Their system shows that it doesn’t have to be the way we do it in the U.S.

After Portugal decriminalized drug use, overdose deaths decreased by 80% and HIV rates went from 52% to 6%. It’s not a perfect model, but it’s so much better.

Despite Challenges To ACA, Florida Enrollment Rises

The annual enrollment period for health plans under the Affordable Care Act is underway and Florida is expected to lead the nation in signups. Despite legal challenges to the law, it remains popular.

The Controversy Around Virginity Testing

NPR’s Michel Martin talks with Sophia Jones, senior editor for The Fuller Project, about the controversy surrounding virginity testing.

You Can Get A Master’s In Medical Cannabis In Maryland

Maryland now offers the country’s first master’s degree in the study of the science and therapeutics of cannabis. Pictured, an employee places a bud into a bottle for a customer at a weed dispensary in Denver, Colo.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Summer Kriegshauser is one of 150 students in the inaugural class of the University of Maryland, Baltimore’s Master of Science in Medical Cannabis Science and Therapeutics, the first graduate program of its type in the country.

This will be Kriegshauser’s second master’s degree and she hopes it will offer her a chance to change careers.

“I didn’t want to quit my really great job and work at a dispensary making $12 to $14 an hour,” says Kriegshauser, who is 40. “I really wanted a scientific basis for learning the properties of cannabis — all the cannabinoids and how they interact with the body. I wanted to learn about dosing. I wanted to learn about all the ailments and how cannabis is used within a medical treatment plan, and I just wasn’t finding that anywhere,” she adds.

The program stands largely alone: Some universities offer one-off classes on marijuana and two have created undergraduate degrees in medicinal plant chemistry, but none have yet gone as far as Maryland.

Stretched over two years and conducted almost exclusively online, the program launched as an increasing number of jurisdictions across the country legalize pot — primarily for medical uses, but in some places recreational, as well.

As of mid-October, nearly three dozen states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands had legalized medical cannabis, creating an ever-expanding universe of opportunities for people looking to grow, process, recommend and sell the drug to patients. And given how quickly attitudes and laws on cannabis are shifting, those opportunities are expected to keep expanding.

But even as the industry has quickly grown, expertise has remained largely informal. And for people looking to change careers, like Kriegshauser, getting into the legal cannabis field can seem risky, with the likely job options hard to come by.

The University of Maryland credits the overwhelming response to its graduate program to that desire for more information and opportunity. More than 500 hopefuls applied for what was supposed to be a class of 50, prompting the university to increase the size of the inaugural class threefold. And the class is geographically diverse, coming from 32 states and D.C., plus Hong Kong and Australia.

The students take four required core courses — including one on the history of medical weed and culture, and two basic science classes. Students then choose between a number of electives.

Leah Sera, a pharmacist and the program’s director, says officials at the university see a parallel trend. More and more of their graduates were entering a professional world where cannabis is seen as an alternative medicine for any number of ailments, and one that more patients are curious about.

“There have been a number of studies, primarily with health professionals, indicating that there is an educational gap related to medical cannabis — that health professionals want more education because patients are coming to them with questions about cannabis and therapeutic uses,” Sera says.

Pharmacist Staci Gruber teaches at Harvard Medical School and is leading one of the country’s most ambitious research projects on medical marijuana at McLean Hospital in Boston.

She says Maryland’s program is proof that as the drug becomes ever more present among patients, more research on its effects will be needed.

“I know some say, ‘Oh, it’s just a moneymaker for the institution,’ but it’s because people are asking for it,” she says. “People are interested in learning more and knowing more, so [Maryland’s program] underscores the need to have more data.”

That’s the challenge for an academic program on cannabis; the drug remains largely illegal under federal law, which has hampered its study over the years and means very little concrete research exists for students to dig into. But as that changes, Sera says, the program will continue to evolve.

And she expects that students will see immediate opportunities in the rapidly expanding industry once they graduate.

There remains plenty of uncertainty, of course, and as the recreational use of weed is made legal in more places, established medical cannabis programs, and their associated jobs, may dwindle. But Summer Kriegshauser says making the leap into Maryland’s program made sense for her — and she bets it will pay off.

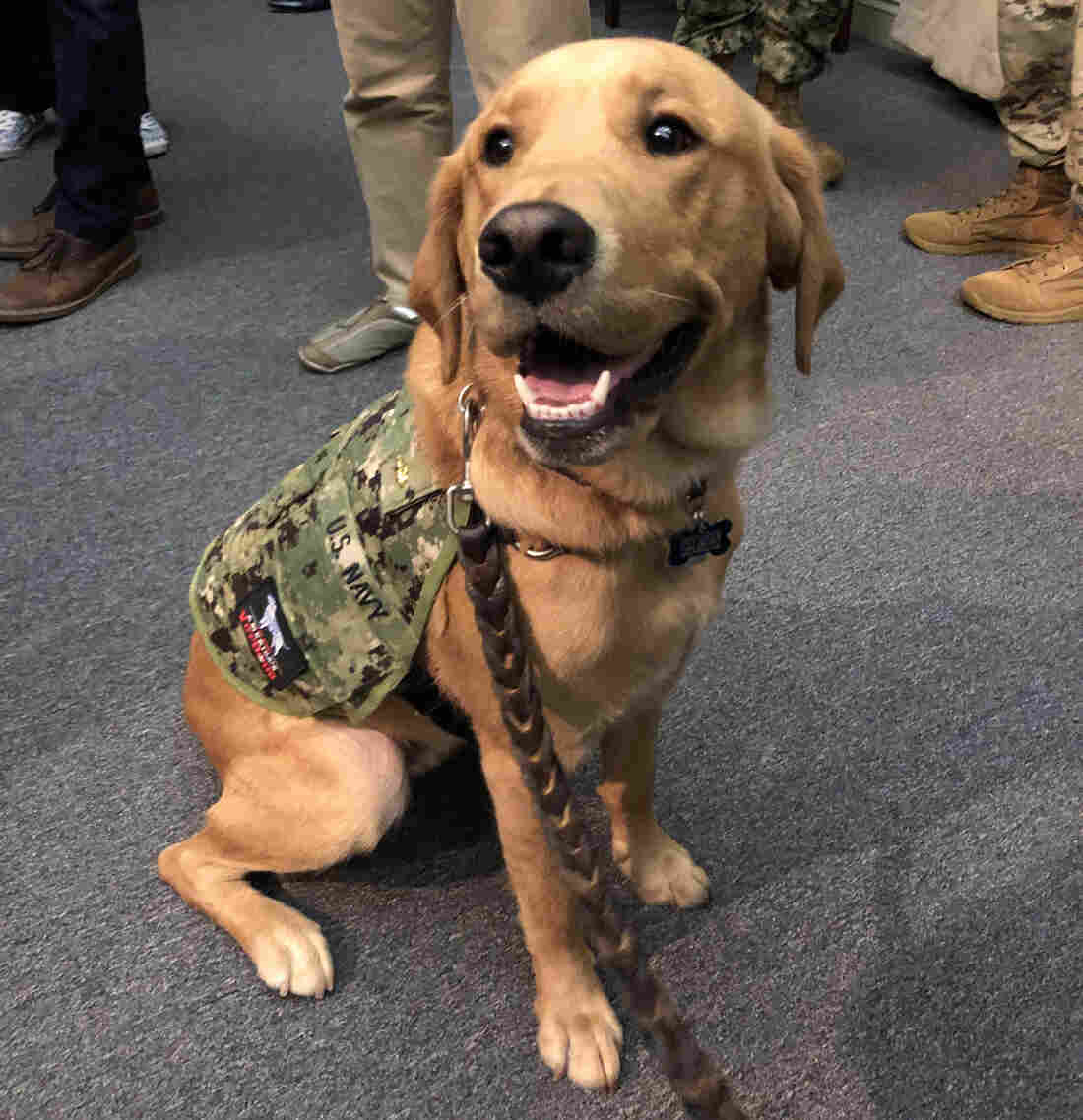

High-Ranking Dog Provides Key Training For Military’s Medical Students

Service dogs can be trained to provide very different types of support to their human companions, as medical students learn from interacting with “Shetland,” a highly skilled retriever-mix.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

The newest faculty member at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences has a great smile ? and likes to be scratched behind the ears.

Shetland, not quite 2 years old, is half-golden retriever, half-Labrador retriever. As of this fall, he is also a lieutenant commander in the Navy and a clinical instructor in the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology at USUHS in Bethesda, Md.

Among Shetland’s skills are “hugging” on command, picking up a fallen object as small as a cellphone and carrying around a small basket filled with candy for harried medical and graduate students who study at the military’s medical school campus.

But Shetland’s job is to provide much more than smiles and a head to pat.

“He is here to teach, not just to lift people’s spirits and provide a little stress relief after exams,” says USUHS Dean Arthur Kellermann. He says students interacting with Shetland are learning “the value of animal-assisted therapy.”

The use of dogs trained to help their human partners with specific tasks of daily life has ballooned since studies in the 1980s and 1990s started to show how animals can benefit human health.

But helper dogs come in many varieties. Service dogs, like guide dogs for the blind, help people with disabilities live more independently. Therapy dogs can be household pets who visit people in hospitals, schools and nursing homes. And then there are highly trained working dogs, like the Belgian Malinois, that recently helped commandos find the Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Shetland is technically a “military facility dog,” trained to provide physical and mental assistance to patients as well as interact with a wide variety of other people.

His military commission does not entitle him to salutes from his human counterparts.

“The ranks are a way of honoring the services [of the dogs] as well as strengthening the bond between the staff, patients and dogs here,” says Mary Constantino, deputy public affairs officer at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. “Our facilities dogs do not wear medals, but do wear rank insignia as well as unit patches.”

USUHS, which trains doctors, dentists, nurses and other health professionals for the military, is on the same campus in suburban Washington, D.C. Two of the seven Walter Reed facility dogs ? Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Sully (the former service dog for President George H.W. Bush) and Marine Sgt. Dillon ? attended Shetland’s formal commissioning ceremony in September as guests.

The Walter Reed dogs, on campus since 2007, earn commissions in the Army, Navy, Air Force or Marines. They wear special vests designating their service and rank. The dogs visit and interact with patients in several medical units, as well as in physical and occupational therapy, and help boost morale for patients’ family members.

But Shetland’s role is very different, says retired Col. Lisa Moores, USUHS associate dean for assessment and professional development.

“Our students are going to work with therapy dogs in their careers and they need to understand what [the dogs] can do and what they can’t do,” she says.

As in civilian life, the military has made significant use of animal-assisted therapy. “When you walk through pretty much any military treatment facility, you see therapy dogs walking around in clinics, in the hospitals, even in the ICUs,” says Moores. Dogs also play a key role in helping service members who have post-traumatic stress disorder.

Students need to learn who “the right patient is for a dog, or some other therapy animal,” she says. “And by having Shetland here, we can incorporate that into the curriculum, so it’s another tool the students know they have for their patients someday.”

The students, not surprisingly, are thrilled by their newest teacher.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, says the Walter Reed dogs used to visit the school’s 1,500 students and faculty fairly regularly, but “having Shetland here all the time is optimal.” Wyatt says the only thing she knew about service dogs before — or at least thought she knew — was that “you’re not supposed to pet them.” But Shetland acts as both a service dog and a therapy dog, so can be petted, Wyatt learned.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, shares a hug with Shetland. The dog’s military commission does not entitle him to salutes.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

Having Shetland around helps the students see “there’s a difference,” Wyatt says, and understand how that difference plays out in a health care setting. Like his colleagues Sully and Dillon, Shetland was bred and trained by America’s VetDogs.

The New York nonprofit provides dogs for “stress control” for active-duty military missions overseas, as well as service dogs for disabled veterans and civilian first responders.

Many of the puppies are raised by a team made up of prison inmates (during the week) and families (on the weekends), before returning to New York for formal service dog training. National Hockey League teams such as the Washington Capitals and New York Islanders also raise puppies for the organization.

Dogs can be particularly helpful in treating service members, says Valerie Cramer, manager of America’s VetDogs service dog program. “The military is thinking about resiliency. They’re thinking about well-being, about decompression in the combat zone.”

Often people in pain won’t talk to another person but will open up in front of a dog. “It’s an opportunity to start a conversation as a behavioral health specialist,” Cramer says.

While service dogs teamed with individuals have been trained to perform both physical tasks and emotional ones — such as gently waking a veteran who is having a nightmare — facility dogs like Shetland are special, Cramer says.

“That dog has to work in all different environments with people who are under pressure. It can work for multiple handlers. It can go and visit people; can go visit hospital patients; can knock over bowling pins to entertain, or spend time in bed with a child.”

The military rank the dogs are awarded is no joke. They can be promoted ? as Dillon was from Army specialist to sergeant in 2018 ? or demoted for bad behavior.

“So far,” Kellermann says, “Shetland has a perfect conduct record.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

‘Just The Right Policy’: Pete Buttigieg On His ‘Medicare For All Who Want It’ Plan

Credit: NPR

Don’t see the video? Click here.

The field of 2020 presidential candidates with health care overhaul plans is crowded, and Pete Buttigieg, mayor of South Bend, Ind., is drawing lines of distinction between his and his competitors’ proposals.

“I mean, the reality is, all these beautiful proposals we all put forward, their impact is kind of multiplied by zero if you can’t actually get it through Congress, and it’s one of the reasons why I do favor the approach that I have,” he said.

Democratic presidential candidate Mayor Pete Buttigieg in South Bend, Ind.

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

Buttigieg would offer public health insurance to those who want it while also keeping private health care plans available. Other candidates’ proposals, including “Medicare for All” — backed by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren — would replace the current system with a single-payer, government-run program and eliminate private insurance altogether.

Buttigieg spoke to two undecided Indiana voters and NPR host Scott Simon as part of the network’s Off Script series of interviews with 2020 presidential candidates.

“We make sure that everybody can afford [public health insurance], but we don’t require you to take it. And partly I think that’s just the right policy, because I think people should be able to choose,” he said. “But it’s also really important that that’s a policy that commands the support of most Americans. … We have a moment where we can get something that big done and most Americans want it done. That’s not true of some of the other ideas out there, which would make it much harder to actually achieve them no matter how good they sound in campaign season.”

Mayor Pete Buttigieg, center, at Pegg’s Diner in South Bend, Ind. with undecided voters Michael Logan, left, Jacque Stahl, back to camera, and NPR host Scott Simon.

Lucy Hewitt/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Hewitt/NPR

The voters — Michael Logan, a 54-year-old retired Michigan State Police detective sergeant, and Jacque Stahl, 37, who works with a health care group in South Bend — pressed Buttigieg on his plan.

Stahl’s 5-year-old son has a condition that requires treatment that if uninsured would cost her family $35,000 a month. She said the health care system can be confusing even for those in the industry, and Americans who do their best to stay in-network can be faced with large surprise medical bills.

Jacque Stahl, 37, who works with a health care group in South Bend, Ind., and Michael Logan, a 54-year-old retired Michigan State Police detective sergeant.

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

Buttigieg told her he’s proposing to end surprise billing.

“We would set 200 percent of Medicare, would be the highest that even an out-of-network therapy could cost when you have a hospitalization or something like that,” he said. “Because some of this is also the responsibility of hospitals and health care providers. This can’t just be handled on the insurance side.”

Buttigieg is polling second in Iowa according to a Quinnipiac University poll released Wednesday. The poll shows Buttigieg polling at 19%, trailing Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who is receiving 20%. Iowa holds the first-in-the-nation caucuses on Feb. 3.

Off Script is edited and produced for broadcast by Ashley Brown and Bridget De Chagas. Eric Marrapodi is Off Script’s supervising editor.

HHS Sues Drugmaker Gilead Over PrEP Patent Infringement

The federal government is suing drugmaker Gilead for alleged patent infringement. The suit charges the company violated patents on “PrEP” drugs that are used to prevent HIV infection.

Federal Judge Throws Out ‘Conscience Rights’ Rule For Health Care Workers

A federal judge has thrown out the Trump administration’s “conscience rights” rule for health care workers.

The Air Ambulance Billed More Than The Lung Transplant Surgeon

Tom and Dana Saputo sit in their backyard with their three dogs. Tom Saputo’s double-lung transplant was fully covered by insurance, but he was responsible for an $11,524.79 portion of the charge for an air ambulance ride.

Anna Almendrala/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Almendrala/KHN

Before his double-lung transplant, Tom Saputo thought he had anticipated every possible outcome.

But after the surgery, he wasn’t prepared for the price of the 27-mile air ambulance flight from a hospital in Thousand Oaks, Calif., to UCLA Medical Center — which cost more than the lifesaving operation itself.

“When you look at the bills side by side, and you see that the helicopter costs more than the surgeon who does the lung transplant, it’s ridiculous,” said Dana Saputo, Tom’s wife. “I don’t think anybody would believe me if I said that and didn’t show them the evidence.”

“Balance billing,” better known as surprise billing, occurs when a patient receives care from a medical provider outside of his insurance plan’s network, and then the provider bills the patient for the amount insurance didn’t cover. These bills can soar into the tens of thousands of dollars.

Surprise bills hit an estimated 1 in 6 insured Americans after a stay in the hospital. And the air ambulance industry, with its private equity backing, high upfront costs and frequent out-of-network status, is among the worst offenders.

Share your medical billing story

Do you have a medical bill you’d like us to investigate? You can tell us about it and submit it here.

Congress is considering legislation aimed at addressing surprise bills and air ambulance charges. And some states, including Wyoming and California, are trying to address the problem even though there are limits to what they can do, because air ambulances are primarily regulated by federal aviation authorities.

That regulatory approach leaves patients vulnerable.

Saputo, 63, was diagnosed in 2016 with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a progressive disease that scars lung tissue and makes it increasingly difficult to breathe.

The retired Thousand Oaks graphic designer got on the list for a double-lung transplant at UCLA and started the preapproval process with his insurance company, Anthem Blue Cross, should organs become available.

But before a transplant could be arranged, he suddenly stopped breathing on the evening of July 7, 2018. His wife called 911.

A ground ambulance drove the couple to Los Robles Regional Medical Center, 15 minutes from their house, where Saputo spent four days in the intensive care unit before his doctors sent him to UCLA by air ambulance.

He was on the brink of death, but just in time, the hospital received a pair of donor lungs. They were a perfect match, and two days after arriving at UCLA, Saputo was breathing normally again.

“It was a miracle,” he said.

After Tom Saputo became ill, his dog Lindsey never let him out of her sight. Saputo was diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis in 2016 and underwent a successful double-lung transplant in July 2018.

Anna Almendrala/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Almendrala/KHN

Saputo’s recovery was difficult, and problems like infections put him back in the hospital for observation. But the most unexpected setback was financial.

When Saputo opened a letter from Anthem, he discovered the helicopter company, which was out of his network, had charged the insurance company $51,282 for the flight. Saputo was responsible for the portion his insurance didn’t cover: $11,524.79.

By contrast, the charges from the day of his transplant surgery totaled $40,575 — including $31,605 for his surgeon — and were fully covered by Anthem.

Saputo appealed to Anthem twice about the ambulance charges. Meanwhile, the helicopter company, Mercy Air, kept calling him after he left the hospital, asking him to negotiate with his insurance company. It even called his adult daughter in San Francisco to ask how the Saputos planned to pay the bill.

“I have no idea how they even got her name or her number,” Saputo said.

Mercy Air is a subsidiary of Air Methods, which operates in 48 states and is owned by the private equity firm American Securities.

Air Methods acknowledged by email that it had put Saputo through a “long and arduous process.” The company contacted his daughter because it tried every phone number associated with him, said company spokesman Doug Flanders. But Air Methods laid the blame at the feet of his insurer.

Anthem spokeswoman Leslie Porras said the blame doesn’t lie with insurers, but with air ambulance companies that remain out of network so they can charge patients “whatever they choose.”

“The ability to bill the consumer for the balance provides little incentive for some air ambulance providers to contract with us,” Porras said.

(In January, six months after Saputo’s surgery, Anthem entered into a contract with the air ambulance company to make it an in-network provider, she said.)

Air Methods forgave Saputo’s bill in August after ABC’s Good Morning America, working with Kaiser Health News, inquired about his case. Air Methods said it was an internal decision to zero out his bill.

Other patients usually aren’t as lucky.

The median cost of a helicopter air ambulance flight was $36,400 in 2017, an increase of more than 60% from the median price in 2012, according to a Government Accountability Office analysis. Two-thirds of the flights in 2017 were out of network, the report found.

The air ambulance industry justifies these charges by pointing out that the bulk of its business — transporting patients covered by the public insurance programs Medicare and Medicaid — is underfunded by the government.

The median cost to transport a Medicare patient by air ambulance is about $10,200, according to an industry study. However, air ambulance companies are reimbursed a median rate of $6,500 per flight.

“The remaining 30% of patients with private health insurance end up paying over 70% of the costs,” said Flanders of Air Methods.

But critics argue the real problem is market saturation. While the number of air ambulance helicopters in the U.S. has increased — rising more than 10% from 2010 to 2014 — the number of flights hasn’t, which means air ambulance companies seek to raise prices on each ride.

“This is a great opportunity to make money, because patients don’t ask for the price before they receive the service,” said Ge Bai, an associate professor of accounting and health policy at Johns Hopkins University.

That’s what frustrated the Saputos the most about their air ambulance charge: There was no way they could have shopped around to compare costs beforehand.

“There’s just no possible way that a customer of insurance can navigate that process,” Dana Saputo said.

Bai also criticized the practice of charging privately insured patients exorbitant amounts to make up for losses from Medicaid and Medicare patients.

“If they feel that Medicare and Medicaid is paying too little, they should lobby the government to get a higher reimbursement,” Bai said.

In California, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill in early October that will limit how much some privately insured patients will pay for air ambulance rides. Effective next year, the law, by state Assemblyman Tim Grayson, will cap out-of-pocket costs at patients’ in-network amounts, even if the air ambulance company is out of network.

Wyoming is moving to treat the industry like a public utility, allowing the state’s Medicaid program to cover all of its residents’ air ambulance trips and then bill patients’ health insurance plans. The state would then cap out-of-pocket costs at 2% of the patient’s income or $5,000, whichever is less. Wyoming needs permission from the federal government to proceed.

Ultimately, though, state authority is limited because the federal Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 prohibits states from enacting price laws on air carriers.

Congress is considering several bipartisan bills on surprise billing. One measure by Sens. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., and Patty Murray, D-Wash., would ban balance bills from air ambulance companies. The bill passed committee and is now headed to the Senate floor for a vote, pending approval from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky.

Air Methods said that, in general, it would support federal legislation that would calculate new rates for Medicare reimbursement, as long as they are based on cost data the industry provides.

But there is intense industry opposition to the bill. Combined with the complexity of the legislation (it also includes prescription drug price reform) and competing Senate leadership priorities, the measure faces a rocky path to the president’s desk, said Melissa Lorenzo Williams, manager of health care policy and advocacy at the National Patient Advocate Foundation.

“Despite having bipartisan and bicameral support, I can’t confidently say that this is something that will pass,” Williams said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.