Opioid Case With 2 Ohio Counties As Plaintiffs Set To Go To Trial Next Week

The first federal case against the opioid industry goes to trial Monday. Some companies have settled to avoid trial, others will get their day in court.

The first federal case against the opioid industry goes to trial Monday. Some companies have settled to avoid trial, others will get their day in court.

Fanatic Studio/Getty Images/Collection Mix: Sub

Group Health Cooperative in Seattle, one of the United States’ oldest and most respected nonprofit health insurance plans, is accused of bilking Medicare out of millions of dollars in a federal whistleblower case.

Teresa Ross, a former medical billing manager at the insurer, alleges that it sought to reverse financial losses in 2010 by claiming that some patients were sicker than they were or by billing for medical conditions that patients didn’t actually have. As a result, the insurer retroactively collected an estimated $8 million from Medicare for 2010 services, according to the suit.

Ross filed suit in federal court in Buffalo, N.Y., in 2012, but the suit remained under a court seal until July and is in its initial stages. The suit also names as defendants two medical coding consultants — consulting firm DxID of East Rochester, N.Y., and Independent Health Association, an affiliated health plan in Buffalo, N.Y. All denied wrongdoing in separate court motions filed late Wednesday to dismiss the suit.

The Justice Department has thus far declined to take over the case but said in a June 21 court filing that “an active investigation is ongoing.”

The whistleblower suit is one of at least 18 such cases documented by Kaiser Health News that accuse Medicare Advantage managed care plans of ripping off the government by exaggerating how sick their patients were. The whistleblower cases have emerged as a primary tool for clawing back overpayments. While many of the cases are pending in courts, five have recovered a total of nearly $360 million.

“The fraudulent practices described in this complaint are a product of the belief, common among [Medicare Advantage] organizations, that the law can be violated without meaningful consequence,” Ross alleges.

Medicare Advantage plans are a privately run alternative to traditional Medicare that often offer extra benefits such as dental and vision coverage but limit choice of medical providers. They have exploded in popularity in recent years, enrolling more than 22 million people, just over 1 in 3 of those eligible for Medicare.

Word of another whistleblower alleging Medicare Advantage billing fraud comes as the White House is pushing to expand enrollment in the plans. On Oct. 3, President Trump issued an executive order that permits the plans to offer a range of new benefits to attract patients. One, for instance, is partly covering the cost of Apple watches as an inducement.

Group Health opened for business more than seven decades ago and was among the first managed care plans to contract with Medicare. Formed by a coalition of unions, farmers and local activists, the HMO grew from just a few hundred families to more than 600,000 patients before its members agreed to join California-based Kaiser Permanente. That happened in early 2017, and the plan is now called Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington. (Kaiser Health News is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

In an emailed statement, a Kaiser Permanente spokesperson said: “We believe that Group Health complied with the law by submitting its data in good faith, relying on the recommendations of the vendor as well as communications with the federal government, which has not intervened in the case at this time.”

Ross nods to the plan’s history, saying it has “traditionally catered to the public interest, often highlighting its efforts to support low-income patients and provide affordable, quality care.”

The insurer’s Medicare Advantage plans “have also traditionally been well regarded, receiving accolades from industry groups and Medicare itself,” according to the suit.

But Ross, who worked at Group Health for more than 14 years in jobs involving billing and coding, says that from 2008 through 2010, the company “went from an operating income of almost $57 million to an operating loss of $60 million.” Ross says the losses were “due largely to poor business decisions by company management.”

The lawsuit alleges that the insurer manipulated a Medicare billing formula known as a risk score. The formula is supposed to pay health plans higher rates for sicker patients, but Medicare estimates that overpayments triggered by inflated risk scores have cost taxpayers $30 billion over the past three years alone.

According to Ross, a Group Health executive in 2011 attended a meeting of the Alliance of Community Health Plans, where he heard from a colleague at Independent Health about an “exciting opportunity” to increase risk scores and revenue. The colleague said Independent Health “had made a lot of money” using its consulting company, which specializes in combing patient charts to find overlooked diseases that health plans can bill for retroactively.

In November 2011, Group Health hired the firm DxID to review medical charts for 2010. The review resulted in $12 million in new claims, according to the suit. Under the deal, DxID took a percentage of the claims revenue it generated, which came to about $1.5 million that year, the suit says.

Ross says she and a doctor who later reviewed the charts found “systematic” problems with the firm’s coding practices. In one case, the plan billed for “major depression” in a patient described by his doctor as having an “amazingly sunny disposition.” Overall, about three-quarters of its claims for higher charges in 2010 were not justified, according to the suit. Ross estimated that the consultants submitted some $35 million in new claims to Medicare on behalf of Group Health for 2010 and 2011.

In its motion to dismiss Ross’ case, Group Health called the matter a “difference of opinion between her allegedly ‘conservative’ method for evaluating the underlying documentation for certain medical conditions and her perception of an ‘aggressive’ approach taken by Defendants.”

Independent Health and the DxID consultants took a similar position in their court motion, arguing that Ross “seeks to manufacture a fraud case out of an honest disagreement about the meaning and applicability of unclear, complex, and often conflicting industry-wide coding criteria.”

In a statement, Independent Health spokesman Frank Sava added: “We believe the coding policies being challenged here were lawful and proper and all parties were paid appropriately.”

Whistleblowers sue on behalf of the federal government and can share in any money recovered. Typically, the cases remain under a court seal for years while the Justice Department investigates.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, along with 1,500 self-funded health plans, sued Sutter Health for antitrust violations. The closely watched case, which many expected to set precedents nationwide, ended in a settlement Wednesday. Above, Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif.

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

Sutter Health, a large nonprofit health care system with 24 hospitals, 34 surgery centers and 5,500 physicians across Northern California, has reached a preliminary settlement agreement in a closely watched antitrust case brought by self-funded employers and later joined by California’s Office of the Attorney General.

The agreement was announced in San Francisco Superior Court on Wednesday, just before opening arguments were expected to begin.

Details have not been made public, and the parties declined to talk to reporters. Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo told the jury that details likely will be made public during approval hearings in February or March.

There were audible cheers from the jury following the announcement that the trial, which was expected to last for three months, would not continue.

Sutter, which is based in Sacramento, Calif., stood accused of violating California’s antitrust laws by using its market power to illegally drive up prices.

Health care costs in Northern California, where Sutter is dominant, are 20% to 30% higher than in Southern California, even after adjusting for cost of living, according to a 2018 study from the Nicholas C. Petris Center at the University of California, Berkeley, that was cited in the complaint.

The case was a massive undertaking, representing years of work and millions of pages of documents, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra said before the trial. Sutter was expected to face damages of up to $2.7 billion.

Sutter Health consistently denied the allegations and argued that it used its market power to improve care for patients and expand access to people in rural areas. The chain of health care facilities had $13 billion in operating revenue in 2018.

The case was expected to have nationwide implications on how hospital systems negotiate prices with insurers. It is not yet clear what effect, if any, a settlement agreement would have on Sutter’s tactics or those of other large systems.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

NPR’s Audie Cornish speaks with Dr. Yoram Unguru, a hematologist and oncologist in Baltimore, about a shortage of vincristine, a drug used to treat childhood cancer.

In Hamburg, Germany, estimated life expectancy in the city’s poorer neighborhoods still trails wealthier neighborhoods by 13 years.

Juergen Sack/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Juergen Sack/Getty Images

Researchers around the world hail Germany for its robust health care system: universal coverage, plentiful primary care, low drug prices and minimal out-of-pocket costs for residents.

Unlike in the U.S., the prospect of a large medical bill doesn’t stand in the way of anyone’s treatment.

“Money is a problem in [their lives], but not with us,” says Merangis Qadiri, a health counselor at a clinic in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Hamburg, in northern Germany.

But it turns out that tending to the health needs of low-income patients still presents universal challenges.

As an American health care reporter traveling through Germany, I wanted to learn not only what works, but also where the system falls short. So when I arrived here — in one of the country’s wealthiest cities, with one of its largest concentrations of doctors — economists and researchers directed me to two of the poorest neighborhoods: Veddel and Billstedt, both home to high populations of recent immigrants.

Entering these areas felt like stepping into another city, where even though people have universal insurance, high rates of chronic illnesses such as diabetes, depression and heart disease persist. Treatment and preventive care are difficult to access.

The challenges faced at both outposts ? Poliklinik Veddel and Gesundheit für Billstedt/Horn (literally, “Health for Billstedt and Horn”) ? underscore a point: Universal health care, in and of itself, may be a first step toward increasing a community’s health, but it isn’t a magical solution.

Life expectancy in these areas is estimated to trail that of Hamburg’s wealthier neighborhoods by 13 years ? roughly equivalent to the gap between Piedmont, a particularly wealthy suburb of Oakland, Calif., and its more urban neighbor, West Oakland. In Hamburg, the difference persists even though residents never skip medication or doctors’ visits because of cost.

Medical care is only part of the equation. An array of other factors ? known collectively as the “social determinants of health” ? factor strongly into these populations’ well-being. They include big-picture items like affordable, nutritious food and safe areas to exercise — as well as small ones, like having the time and money to get to the doctor.

In Germany, as in the U.S., these are exceptionally difficult problems to treat.

In its three years of operation, Gesundheit für Billstedt/Horn has been visited by about 3,500 patients — 3% of the population in the two neighborhoods it serves. And maybe half of the people who come for a first visit return for a follow-up, says Qadiri, who works at Billstedt/Horn.

For one thing, many don’t know the health outpost exists. For another, people might not feel they can spare the time from chaotic lives.

To address that problem, the Billstedt site, with its patient rooms up front and a large meeting space in the back, is situated in a bustling mall among shops that include an Afghan bakery, Turkish restaurant and McDonald’s. The outpost doesn’t have doctors onsite, but it employs health counselors, who offer advice on healthy living and guidance on how patients can manage chronic conditions, and communicate with patients’ physicians as needed.

The Poliklinik, located in a separate neighborhood known as Veddel, uses social and community events to get patients in the door. The clinic organizes coffees, shows up at local church events and holds local movie nights. The strategy appears to work, at least somewhat: By 11 a.m. on a Tuesday morning, the brightly decorated waiting rooms are filled with patients waiting to see a doctor or other health professional.

The Hamburg neighborhood of Veddel, a 20-minute bike ride from the city’s downtown, is home to many recent immigrants.

Shefali Luthra/Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Shefali Luthra/Kaiser Health News

Still, Poliklinik sees only about 850 unique patients every three months, far short of the area’s 5,000 residents, says Dr. Phillip Dickel, a general practitioner at the clinic.

Another limit on the clinic’s ability to meet need: a shortage of doctors willing to work in this part of town. That includes general practitioners, to say nothing of gynecologists, mental health specialists and pediatricians ? few of whom practice in the area, he adds. In theory, one could take public transit to another part of the city to find a doctor, but that involves time and money for the commute.

Meanwhile, the environmental problems that plague these areas are in some ways more intractable, Dickel says.

Poliklinik’s neighborhood, for instance, is just off the autobahn and filled with old industrial warehouses and factories.

That creates lower air quality and higher risks of asthma and lung diseases, Dickel says. Patients in all these neighborhoods confront housing shortages, so families become overcrowded in small flats. Aside from the psychological toll, illnesses and infections ? influenza, a cold or something more serious ? spread quickly.

While the clinics advocate for improved housing, sometimes the best the staffers at the clinics can do is give advice on how to minimize housing-related health risks.

Qadiri, the Gesundheit health counselor, tries to help patients with diabetes and heart disease find and incorporate fruits and vegetables in their diets and teaches them strategies to replace sugary beverages. She also encourages them to attend onsite exercise classes.

But nutritious food is harder to find in the areas these clinics serve than in one of Hamburg’s wealthier neighborhoods. And fresh produce costs more than fast food.

“People can get care in Germany if they need it,” Dickel says. “Much more important [than access], I would say, are the social conditions. That’s the cause of the life-expectancy gap.”

The Arthur F. Burns Fellowship is an exchange program for German, American and Canadian journalists operated by the International Center for Journalists and the Internationale Journalisten-Programme.

Kaiser Health News a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

President Trump talked to seniors about health care in central Florida in early October. “We eliminated Obamacare’s horrible, horrible, very expensive and very unfair, unpopular individual mandate,” Trump told the crowd.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

The very day President Trump was sworn in — Jan. 20, 2017 — he signed an executive order instructing administration officials “to waive, defer, grant exemptions from, or delay” implementing parts of the Affordable Care Act, while Congress got ready to repeal and replace Barack Obama’s signature health law.

Months later, repeal and replace didn’t work, after the late Arizona Sen. John McCain’s dramatic thumbs down on a crucial vote (Trump still frequently mentions this moment in his speeches and rallies, including in his recent speech on Medicare).

After that, the president and his administration shifted to a piecemeal approach, as they tried to take apart the ACA. “ObamaCare is a broken mess,” the president tweeted in the fall of 2017, after repeal in Congress had failed. “Piece by piece, we will now begin the process of giving America the great HealthCare it deserves!”

Two years later, what has his administration done to change the ACA, and who’s been affected? Below are five of the biggest changes to the federal health law under President Trump.

1. Individual mandate eliminated

What is it? The individual mandate is the requirement that all U.S. residents either have health insurance or pay a penalty. The mandate was intended to help keep the premiums for ACA policies low by ensuring that more healthy people entered the health insurance market.

What changed? The 2017 Republican-backed tax overhaul legislation reduced the penalty for not having insurance to zero.

What does the administration say? “We eliminated Obamacare’s horrible, horrible, very expensive and very unfair, unpopular individual mandate. A total disaster. That was a big penalty. That was a big thing. Where you paid a lot of money for the privilege […] of having no healthcare.” — President Trump, The Villages, Florida, Oct. 3, 2019

What’s the impact? First of all, getting rid of the penalty for skipping insurance opened a new avenue of attack against the entire ACA in the courts, via the Texas v. Azar lawsuit. Back in 2012, the ACA had been upheld as constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, because the penalty was essentially a tax, and Congress is allowed to create a new tax. Last December, though, a federal judge in Texas ruled that now that the penalty is zero dollars, it’s a command, not a tax, and is therefore unconstitutional. He also reasoned that it cannot be cut off from the rest of the law, so he judged the whole law to be unconstitutional. A decision from the appeals court is expected any day now.

Eliminating the penalty also caused insurance premiums to rise, says Sabrina Corlette, director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University. “Insurance companies were getting very strong signals from the Trump administration that even if the ACA wasn’t repealed, the Trump administration probably was not going to enforce the individual mandate,” she says. Insurance companies figured that without a financial penalty, healthy people would opt not to buy insurance, and the pool of those that remained would be smaller and sicker.

So, even though the zero-dollar-penalty didn’t actually go into effect until 2019, Corlette says, “insurance companies — in anticipation of the individual mandate going away and in anticipation that consumers would believe that the individual mandate was no longer going to be enforced — priced for that for 2018.” According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, premiums went up about 32%, on average, for ACA “silver plans” that went into effect in early 2018, although most people received subsidies to off-set those premium hikes.

2. States allowed to add “work requirements” to Medicaid

What is it? Medicaid expansion was a key part of the ACA. The federal government helped pay for states (that chose to) to expand Medicaid eligibility beyond families to include all low-income adults; and to raise the income threshold, so that more people would be eligible. So far, 37 states and D.C. have opted to expand Medicaid.

What changed? Under Trump, if they get approval from the federal government, states can now require Medicaid beneficiaries to prove with documentation that they either work or go to school.

What does the administration say? “When you consider that, less than five years ago, Medicaid was expanded to nearly 15 million new working-age adults, it’s fair that states want to add community engagement requirements for those with the ability to meet them. It’s easier to give someone a card; it’s much harder to build a ladder to help people climb their way out of poverty. But even though it is harder, it’s the right thing to do.” — Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Washington, D.C., Sept. 27, 2018

What’s the impact? Even though HealthCare.gov and the state insurance exchanges get a lot of attention, the majority of people who gained health care coverage after the passage of the ACA — 12.7 million people — actually got their coverage by being newly able to enroll in Medicaid.

Medicaid expansion has proven to be quite popular. And in the 2018 election, three more red states — Idaho, Nebaska, and Utah — voted to join in. Right now, 18 states have applied to the federal government to implement work requirements; but most such programs haven’t yet gone into effect.

“The one work requirement program that’s actually gone into effect is in Arkansas,” says Nicholas Bagley, professor of law at the University of Michigan and a close follower of the ACA. “We now have good data indicating that tens of thousands of people were kicked off of Medicaid, not because they were ineligible under the work requirement program, but because they had trouble actually following through on the reporting requirements — dealing with websites, trying to figure out how to report hours effectively, and all the rest.”

If more states are able to implement work requirements, Bagley says, that could lead “to the loss of coverage for tens of thousands — or even hundreds of thousands — of people.”

CMS administrator Verma has pushed back on the idea that these requirements are “some subversive attempt to just kick people off of Medicaid.” Instead, she says, “their aim is to put beneficiaries in control with the right incentives to live healthier, independent lives.”

Work requirements in Arkansas and Kentucky were put on hold by a federal judge in March, and those cases are on appeal. The issue is likely headed to the Supreme Court.

3. Cost-sharing reduction subsidies to insurers have ended.

What is it? Payments from the federal government to insurers to motivate them to stay in the ACA insurance exchanges and help keep premiums down.

What changed? The Trump administration suddenly stopped paying these subsides in 2017.

What does the administration say? “I knocked out the hundreds of millions of dollars a month being paid back to the insurance companies by politicians. […] This is money that goes to the insurance companies to line their pockets, to raise up their stock prices. And they’ve had a record run. They’ve had an incredible run, and it’s not appropriate.” — President Trump, the White House, Oct 17, 2017

What’s the impact? This change had a strange and unexpected impact on the new insurance markets set up by the ACA. Insurers were in a bind: They had to offer subsidies to low-income people applying for insurance, but the federal government was no longer reimbursing them.

“The first thinking [was], ‘Oh gosh, that’s going to cause premiums to go up, and it’s going to hurt the marketplace,’ ” says Christine Eibner, who tracks the ACA at the nonpartisan RAND corporation. “What ended up happening is, insurers, by and large, addressed this by increasing the price of the silver plan on the health insurance exchanges.”

This pricing strategy was nicknamed “silver loading.” Because the silver plan is the one used to calculate tax credits, the Trump administration still ended up paying to subsidize people’s premiums, but in a different way. In fact, “it has probably led to an increase in federal spending” to help people afford marketplace premiums, Eibner says.

“Where the real damage has been done is for folks who aren’t eligible for subsidies — who are making just a little bit too much for those subsidies,” adds Corlette. “They really are priced out of comprehensive ACA-compliant insurance.”

4. Access to short-term “skinny” plans has been expanded

What is it? The ACA initially established rules that health plans sold on HealthCare.gov and state exchanges had to cover people with pre-existing conditions and had to provide certain “essential benefits.” President Obama limited any short-term insurance policies that did not provide those benefits to a maximum duration of three months. (The original idea of these policies is that they can serve as a helpful bridge for people between school and a job, for example.)

What changed? The Trump administration issued a rule last year that allowed these short-term plans to last 364 days and to be renewable for three years.

What does the administration say? “We took swift action to open short-term health plans and association health plans to millions and millions of Americans. Many of these options are already reducing the cost of health insurance premiums by up to 60% and, really, more than that.” President Trump, The White House, June 14, 2019

What’s the impact? The new rule went into effect last October, though availability of these short-term or “skinny” plans varies depending on where you live — some states have passed their own laws that either limit or expand access to them. Some federal actuaries projected lots of people would leave ACA marketplaces to get these cheaper plans; they said that would likely increase the size of premiums paid by people who buy more comprehensive coverage on the ACA exchanges. But a recent analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation finds that the ACA marketplaces have actually stayed pretty stable.

Still, there’s another consequence of expanding access to these less comprehensive plans: “People who get these “skinny” plans aren’t really fully protected in the event that they have a serious health condition and need to use their insurance,” Eibner says. “They may find that it doesn’t cover everything that they would have been covered for, under an ACA-compliant plan.”

For instance, you might pay only $70 a month in premiums, but have a deductible that’s $12,500 — so if you get really sick or get into an accident, you could be in serious financial straits.

5. Funds to facilitate HealthCare.gov sign-ups slashed.

What is it? The ACA created Navigator programs and an advertising budget to help people figure out specifics of the new federally run insurance exchanges and sign up for coverage.

What changed? In August 2017, the administration significantly cut federal funding for these programs.

What does the administration say? “It’s time for the Navigator program to evolve […] This decision reflects CMS’ commitment to put federal dollars for the federally facilitated Exchanges to their most cost effective use in order to better support consumers through the enrollment process.” — CMS Administrator Seema Verma, written statement, July 10, 2018

What’s the impact? It’s hard to document what the impact of this particular cut was on enrollment. The cuts were uneven, and some states and cities got creative to keep providing services. “We have seen erosion in overall health insurance coverage,” says Corlette. “But it’s hard to know whether that’s the effect of the individual mandate going away, the short term plans or the reductions in marketing and outreach — it’s really hard to tease out the impact of those three changes.”

Overall, Nicholas Bagley says, the ACA has been “pretty resilient to everything, so far, that the Trump administration has thrown at it.” Some of Trump’s efforts to hobble the law have been caught up in the courts; others have not gone into effect. And, despite efforts to lure people away from the individual insurance marketplaces or to make ACA policies unaffordable, “the marketplaces have proved themselves to be remarkably resilient,” Corlette says.

Abbe Gluck, director of the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy at Yale, cautions that though the law has proven to be stronger than expected, all these actions by the Trump administration have, indeed, had an effect.

“These actions have been designed to depress enrollment — they have depressed enrollment,” she says. “They have increased insurance prices.” Also, the uninsurance rate for U.S. residents also went up in 2018 for the first time since before the ACA was passed.

Despite that, one of the things that have kept the marketplaces as strong as they are, Gluck notes, is that they’re not all run by the federal government.

“Since the Affordable Care Act is implemented half by state governments — mostly blue states — those state governments have been able to resist these sabotaging efforts,” Gluck says.

“They have been able to extend enrollment, and they have been able to do outreach, because they run their own insurance markets. And in those states there is already evidence that sabotage attacks have not been felt as strongly.”

The piecemeal attacks on the ACA have made many people nervous about the future of their health coverage, Gluck says. “The most important theme of [Trump’s] administration of the ACA has been to sow uncertainty into the market and destabilize the insurance pool,” she says.

With open enrollment for 2020 health plans set to kick off in just a few weeks, Bagley wants people to know the ACA is still strong.

The federal health law “has been battered,” Bagley says. “It has been bruised. But it is still very much alive.”

The latest challenge to the Affordable Care Act, Texas v. Azar, was argued in July in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. Attorney Robert Henneke, representing the plaintiffs, spoke outside the courthouse on July 9.

Gerald Herbert/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Gerald Herbert/AP

A decision in the latest court case to threaten the future of the Affordable Care Act could come as soon as this month. The ruling will come from the panel of judges in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which heard oral arguments in the Texas v. Azar lawsuit.

An estimated 24 million people get their health coverage through programs created under the law, which has faced countless court challenges since it passed.

In court in July, only two of the three judges — both appointed by Republican presidents — asked questions. “Oral argument in front of the circuit went about as badly for the defenders of the Affordable Care Act as it could have gone,” says Nicholas Bagley, a professor of law at the University of Michigan. “To the extent that oral argument offers an insight into how judges are thinking about the case, I think we should be prepared for the worst — the invalidation of all or a significant part of the Affordable Care Act.”

Important caveat: Regardless of this ruling, the Affordable Care Act is still the law of the land. Whatever the 5th Circuit rules, it will be a long time before anything actually changes. Still, the timing of the ruling matters, says Sabrina Corlette, director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University.

“If that decision comes out before or during open enrollment, it could lead to a lot of consumer confusion about the security of their coverage and may actually discourage people from enrolling, which I think would be a bad thing,” she says.

Don’t be confused. Open enrollment begins Nov. 1 and runs at least through Dec. 15, and the insurance marketplaces set up by the law aren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

That’s not to underplay the stakes here. Down the line, sometime next year, if the Supreme Court ends up taking the case and ruling the ACA unconstitutional, “the chaos that would ensue is almost possible impossible to wrap your brain around,” Corlette says. “The marketplaces would just simply disappear and millions of people would become uninsured overnight, probably leaving hospitals and doctors with millions and millions of dollars in unpaid medical bills. Medicaid expansion would disappear overnight.

“I don’t see any sector of our health care economy being untouched or unaffected,” she adds.

So what is this case that — yet again — threatens the Affordable Care Act’s very existence?

A quick refresher: When the Republican-led Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, it zeroed out the Affordable Care Act’s penalty for people who did not have health insurance. That penalty was a key part of the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the law in 2012, so after the change to the penalty, the ACA’s opponents decided to challenge it anew.

Significantly, the Trump administration decided in June not to defend the ACA in this case. “It’s extremely rare for an administration not to defend the constitutionality of an existing law,” says Abbe Gluck, a law professor and the director of the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy at Yale University. “The administration is not defending any of it — that’s a really big deal.”

The basic argument made by the state of Texas and the other plaintiffs? The zero dollar fine now outlined in the ACA is a “naked, penalty-free command to buy insurance,” says Bagley.

Here’s how the argument goes, as Bagley explains it: “We know from the Supreme Court’s first decision on the individual mandate case that Congress doesn’t have the power to adopt a freestanding mandate, it just has the power to impose a tax.” So therefore, the argument is that “the naked mandate that remains in the Affordable Care Act must be unconstitutional.”

The case made by the plaintiffs goes further, asserting that because the individual mandate was described by the Congress that enacted it as essential to the functioning of the law, this unconstitutional command cannot be cut off from the rest of the law. If the zero dollar penalty is unconstitutional, the whole law must fall.

Last December, a federal judge in Texas agreed with that entire argument. His judgement was appealed to the panel of judges in the 5th Circuit. Even if those judges agree that the whole law is unconstitutional, that would not be the end of the story — the case will almost certainly end up before the Supreme Court. It would be the third case to challenge the Affordable Care Act in the nation’s highest court.

So if the ruling will be appealed anyway, does it matter? “It matters for at least two reasons,” Bagley says. “First of all, if the 5th Circuit rejects the lower court holding and decides that the whole law is, in fact, perfectly constitutional, I think there’s a good chance the Supreme Court would sit this one out.”

On the other hand, if the 5th Circuit invalidates the law, it almost certainly will go the Supreme Court, “which will take a fresh look at the legal question,” he says. Even if the Supreme Court ultimately decides whether the ACA stands, “you never want to discount the role that lower court decisions can play over the lifespan of a case,” Bagley says.

The law has been dogged by legal challenges and repeal attempts from the very beginning, and experts have warned many times about the dire consequences of the law suddenly going away. Nine years in, “the Affordable Care Act is now part of the plumbing of our nation’s health care system,” Bagley says. “Ripping it out would cause untold damage and would create a whole lot of uncertainty.”

A month after Hurricane Dorian devastated the Bahamas, Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance gets a hug from husband Ferrier Petit Homme. The storm destroyed their home on Grand Abaco Island. They are now living with China Laguerre in Nassau.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Editor’s note: This story includes images that some readers may find disturbing.

Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance was crying on the side of a road when China Laguerre spotted her.

Hurricane Dorian destroyed LaFrance’s newly constructed house in Great Abaco Island on the northern edge of the Bahamas the same night she moved in. That was on Sept. 1.

She then moved into a hotel offering free shelter in Nassau with her husband and 14-year-old son. But she says they were kicked out when staff found her son talking to guests.

She had nowhere to go. So Laguerre invited her to come stay at the home she shares with her parents and her brother.

Bodies lay in the debris left by Hurricane Dorian, which decimated Marsh Harbour on Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas on Sept. 6. The Mudd, an immigrant shantytown in Marsh Harbour, was home to about 8,000 Haitians, some of whom have lived in the area for several generations.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

“If these people didn’t help, I didn’t know what we were going to do,” says LaFrance. “I just thank God for these people.”

LaFrance is one of thousands of Haitians who lived in Abaco but were displaced to Nassau after the storm. The government’s policy is to keep evacuees off Abaco until power, water and housing is restored.

But life in Nassau is not easy for evacuees: Haitians in the Bahamas — some recent immigrants, others who have lived in the Bahamas for generations — say that they face discrimination by their Bahamanian neighbors and that government officials that has made it harder to access emergency aid, shelter and health care and to find jobs to get back on their feet after the storm. On Oct. 2, Prime Minister Hubert Minnis announced that Haitians in the Bahamas without documentation would be deported.

So some are relying on the kindness of strangers — and Laguerre’s home has emerged as the headquarters of an ad hoc Haitian community support network.

Ferrier Petit Homme (left) and Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance pray every evening with other Dorian evacuees as well as members of the Laguerre family, who welcomed them into their home. This night was particularly painful: Sherrine’s 14-year-old son ran away in the morning. He returned two days later.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

While volunteering at a local hospital after the storm, Laguerre, 31, met Haitian evacuees who inspired her to open her doors to strangers.

“I feel sorry because it could’ve been me,” she says.

From left: Justin Bain, Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance and Ferrier Petit Homme have little space to sleep in the family home of China and brother Odne Laguerre, who have taken in 10 Haitian evacuees from Abaco.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Laguerre was born and raised in the Bahamas, but her parents are of Haitian descent. Despite not having enough money to pay their water bill, they have taken in 10 Haitian evacuees from four different families. They pool together what resources they can to grocery shop and cook for everybody in their compound.

“I wouldn’t say the floor is comfortable because it’s just cement,” she says. “We just let them put a sheet on the floor, and they sleep on the ground like that.”

Abaco evacuee Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance shows a photo of herself during better times. LaFrance is one of thousands of Haitians who were displaced to Nassau after Hurricane Dorian.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

The families are still working through the physical and psychological effects of the storm. Lacieuse Timothee of Treasure Cay spent two days buried beneath debris before her sons found her. At the Laguerre home, she spends most of her time in bed. She says she is partially paralyzed, and the injuries around her feet have begun to turn black.

Evacuee Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance (right) tries to find an apartment to rent in Nassau. She’s being helped by family friends Benette Lutus (left) and Kenisher Lutus (center), who are with their 2-year-old daughter.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Laguerre and her parents do not have enough room in their home to keep welcoming guests. But they help those in need however they can. Recently, Laguerre referred a young mother to a friend’s house so she wouldn’t be left on the street with her child.

“I am not employed, but by the goodness of my heart — and I believe in God — this is God’s work here I am doing,” she says.

“Bahamians only” is printed on an advertisement for an apartment in Nassau. Some recent immigrants and others who have lived in the Bahamas for generations say that they face discrimination by their Bahamanian neighbors.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

For now, LaFrance’s family is living off the small amount of money that their relatives send from Haiti. They’re unsure when things will start to look up.

Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance (in print dress) meets about an apartment to rent in Nassau.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

“You can’t even sleep. You have nightmares. You feel like you’re still in the storm,” says LaFrance, more than a month after Hurricane Dorian made landfall. “If you see a little rain, you think the storm is coming again.”

Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance weeps as she recounts how her relatives who live in Nassau turned their backs on her after her home was decimated by Hurricane Dorian.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

A month after Hurricane Dorian devastated the Bahamas, 14,000 people are still displaced and living in shelters like the Kendal Isaacs Gymnasium in Nassau. On Oct. 5, evacuees complained that the building temperature was so low that many spent time outdoors.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Lacieuse Timothee has sores that are turning black. A doctor diagnosed her with gangrene. She was injured after her home collapsed on her during the hurricane.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Bobson Timothee, 23, right, looks in on his mother, Lacieuse. who spends most of her time in bed.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

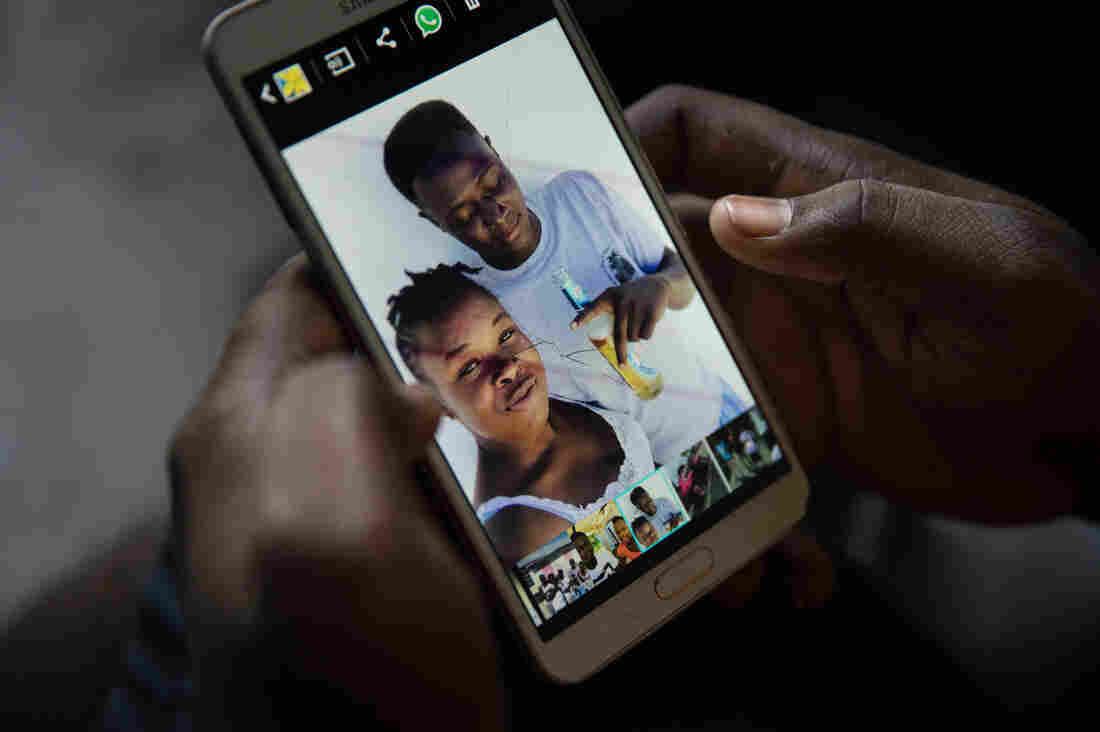

Bobson Timothee keeps a photo on his phone of himself with his best friend, Stephanie Forestal, who died during the storm.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Rolin Timothee sits at the doorway of the room in the home of China Laguerre where he and his wife, Lacieuse, stay as guests.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Ten evacuees from four different families are crowded into the six rooms of China Laguerre’s home.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Odne Laguerre (left) and evacuee Bobson Timothee pass the time while other evacuees play cards at the Laguerre home.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

The home of China Laguerre and her family has emerged as the headquarters of an ad hoc Haitian community support network.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Abaco evacuee and Haitian immigrant to the Bahamas Micilia Etienne, 59, listens to news from Haiti while she and her family take shelter in China Laguerre’s home.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

The border patrol rounds up undocumented Haitian immigrants in Nassau on Sept. 30. Two days later, Prime Minister Hubert Minnis announced that Haitians in the Bahamas without documentation would be deported.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Already, Health Canada has posted safety and efficacy data online for four newly approved drugs; it plans to release reports for another 13 drugs and three medical devices approved or rejected since March.

Teerapat Seedafong/EyeEm/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Teerapat Seedafong/EyeEm/Getty Images

Last March, Canada’s department of health changed the way it handles the huge amount of data that companies submit when seeking approval for a new drug, biological treatment, or medical device — or a new use for an existing one. For the first time, Health Canada is making large chunks of this information publicly available after it approves or rejects applications.

Within 120 days of a decision, Health Canada will post clinical study reports on a new government online portal, starting with drugs that contain novel active ingredients and adding devices and other drugs over a four-year phase-in period. These company-generated documents, often running more than 1,000 pages, summarize the methods, goals, and results of clinical trials, which test the safety and efficacy of promising medical interventions. The reports play an important role in helping regulators make their decisions, along with other information, such as raw data about individual patients in clinical trials.

So far, Health Canada has posted reports for four newly approved drugs — one to treat plaque psoriasis in adults, two to treat two different types of skin cancer, and the fourth for advanced hormone-related breast cancer — and is preparing to release reports for another 13 drugs and three medical devices approved or rejected since March.

Canada’s move follows a similar policy enacted four years ago by the European Medicines Agency of the European Union. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, on the other hand, continues to treat this information as confidential to companies and rarely makes it public.

The argument for more transparency

Transparency advocates say clinical study reports need to be made public in order to understand how regulators make decisions and to independently assess the safety and efficacy of a drug or device. They also say the reports provide medical societies with more thorough data to establish guidelines for a treatment’s use, and to determine whether articles about clinical trials published in medical journals — a key source of information for clinicians and medical societies — are accurate.

“Sometimes regulators miss things that have been hidden in those clinical study reports,” says Matthew Herder, director of the Health Law Institute at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. “Regulators often face resource constraints, they have deadlines, other priorities.”

Last year, for example, Canadian researchers used a clinical study report and other previously non-public information from a clinical trial to call into question the efficacy of Diclectin (known as Diclegis in the United States), a commonly prescribed drug to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. The team had requested the information from Health Canada under an older policy, which required researchers to sign a confidentiality agreement and keep the underlying data secret when they published their results. (It “had a chilling effect,” Herder says of the now-discontinued policy, and not many researchers made requests.)

Duchesnay, the Quebec-based manufacturer of Diclectin, defended the drug, and the Canadian and American professional societies of obstetricians and gynecologists continue to recommend it. Yet the new analysis gave pause to the College of Family Physicians of Canada, which had previously published two articles recommending Diclectin’s use in its medical journal, Canadian Family Physician. The organization took the unusual step in January of publishing a correction, which criticized the independence and accuracy of the two earlier articles. And, citing the new research, it advised physicians to use caution when interpreting recommendations for the drug’s use.

Herder and other lawyers and independent researchers who want to see greater transparency in medical research are urging the FDA to follow the example of Canada and the E.U., but without success thus far. To date, the European program, which has been in effect since 2016, has posted clinical study reports for 132 medicinal products whose applications were submitted after January 2015.

Canadian and European regulators lead the way

It is important to have multiple regulators making the data public, says Peter Doshi, an associate editor at the BMJ, an international medical journal, and an associate professor of pharmaceutical health services research at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. As it stands now, “If FDA approves first, which often it does, we won’t know anything until Health Canada or the EMA makes a decision,” says Doshi. “And not every drug, device, biologic out there is going to be approved by these other regulators or even submitted to these other markets.”

In addition, redundancy lessens the impact if one regulator changes policy. The EMA, for example, earlier this year moved its operations from London to Amsterdam because of Britain’s anticipated exit from the European Union. Clinical data publication “was one of the activities suspended until we are more settled in Amsterdam,” says Anne-Sophie Henry-Eude, head of documents access and clinical data publication. No date has yet been announced for its resumption.

Sandy Walsh, a spokesperson for the FDA, says the agency does not have the same freedom as Canadian and European regulators to release clinical study reports. “U.S. laws on disclosure of trade secret, confidential commercial information, and personal privacy information differ from those governing EMA and Health Canada’s disclosure of clinical study reports,” she wrote in an email.

Some legal experts argue the FDA has more flexibility than it acknowledges. Federal agencies are “entitled to substantial deference” in determining “what constitutes confidential commercial information,” Amy Kapczynski, a Yale law professor and a co-director of the university’s Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency, in The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics.

Why drugmakers balk

In response to an interview request sent to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Megan Van Etten, the trade group’s senior director for public affairs, emailed a statement expressing concern from the industry that Health Canada’s new regulations “could discourage investment in biomedical research by revealing confidential commercial information.”

Joseph Ross, an associate professor of medicine and public health at Yale University and a co-director, along with Kapczynski and others, of CRIT, maintains that clinical study reports contain little information that companies need to keep secret, and that any such information could be redacted before release. A 2015 report by the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, also called for the FDA to release redacted clinical study reports.

That is the strategy of Health Canada, which discusses possible redactions with the manufacturer. “Health Canada retains the final decision on what information is redacted and published,” Geoffroy Legault-Thivierge, a spokesperson, wrote in an email.

So does the EMA, which goes through a similar negotiating process with manufacturers. “We often are in disagreement but at least there is a dialogue,” says Henry-Eude. The EMA might agree to redact manufacturing details, for example.

Journal reports often underplay harms, emphasize benefits

Researchers who independently re-evaluate drugs say the reports are critical because the data they need is not readily available in medical journal articles. One analysis showed that only about half of clinical trials examined were written up in journals in a timely fashion and a third went unpublished. And when articles are published, they contain much less data than the reports, says Tom Jefferson, an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Cochrane, an international collaboration of researchers who conduct and publish reviews of the scientific evidence for medical treatments.

In addition, “journal articles emphasize benefits and underplay or, in some cases, even ignore harms” that can be found in the clinical study report data, says Jefferson. An analysis by experts at the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care in Cologne, Germany, found “considerable” bias in how patient outcomes were reported in journal articles and other publicly available sources. Public access to clinical study reports can shine a light on such discrepancies.

The FDA has flirted in the past with releasing clinical study reports to the public. In January 2018, it launched a pilot program to post portions of reports for up to nine recently approved drugs if the drug companies would agree.

“We’re committed to enhancing transparency about the work we do at the FDA,” commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who resigned in March, said at the time.

But only Janssen Biotech, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, volunteered, and its prostate cancer drug Erleada is the lone entry. In June, the FDA announced it is considering shifting its focus from the pilot program to another designed to better communicate the analyses of FDA experts who review drug applications, which the agency has been making public for approved medicinal products since 2012.

But these analyses by FDA reviewers are no substitute for the actual clinical study reports, says Doshi. The reviews reflect “an FDA scientist’s take on the sponsor’s application,” he said. “Without the clinical study report, somebody like me is largely deprived of looking at the underlying data and developing my own take.”

Independent researchers like those who took a hard look at Diclectin also want access to clinical study reports connected to regulatory decisions made before the European and Canadian portals were opened.

Since 2010, the EMA has been providing researchers and others with access to clinical study reports for such legacy drugs upon request, while Health Canada is even more transparent, posting requested clinical study reports for drugs and devices approved or rejected before March to its new online portal for anyone to see. So far, 12 information packages are available for older drugs and devices and 11 more requests are being processed.

The FDA has, on occasion, provided reports in response to a Freedom of Information Act request, but researchers seeking this information typically invest “a tremendous amount of time and effort,” says Ross. For example, a Yale Law School clinic sued the FDA on behalf of two public health advocacy groups after the agency said it could take years to respond to their FOIA request for clinical trial data for two hepatitis C drugs. In 2017, it won the case and the groups received the data, which they are currently evaluating.

The FDA does not keep track of how many clinical study reports it has released through FOIA, says Walsh. But Doshi and others say such releases are rare, and usually a result of lawsuits or the threat of legal action. In 2011, Doshi requested clinical study reports for Tamiflu, an antiviral medication used to treat the flu. “Eight years later, I think those requests are still alive,” he says now. “I don’t remember getting a denial. They just sit.”

Outside researchers can appeal to companies directly for access to clinical study reports. At least 24 of PhRMA’s 35-member companies have signed on to its six-year-old principles for “responsible clinical trial data sharing,” committing to the release of synopses of clinical study reports for approved medicines and to considering requests for data and the full reports from “qualified” medical and scientific researchers who submit research proposals.

But researchers are concerned they won’t be granted access if companies are not comfortable or sympathetic to their proposals, says Herder. And the companies control the amount of redaction.

The British-based pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has gone further than most in providing public access to its data. In 2013, the company began posting clinical study reports through its own online portal, Clinical Study Register, which is open to the public. “We have published over 2,500 clinical study reports and nearly 6,000 summaries of results — both positive and negative — from our trials on Clinical Study Register,” Andrew Freeman, director and head of medical policy, said in an emailed statement. “GSK is leading the industry in transparency.”

Even so, GSK controls the level of redaction, says Jefferson of Cochrane, who tried to use clinical study reports posted on the company’s portal for a systematic review of HPV vaccines. “Important aspects, for instance the narratives of serious adverse events — those are all blocked out. Big black boxes,” he says. “So they are of moderate use.”

Meanwhile, many researchers do not realize that Health Canada and the EMA are making clinical study reports available. An online survey of 160 researchers around the world who conduct systematic reviews found that 133 “had never considered accessing regulatory data” and 117 of those 133 “were not aware (or were unsure) of where to access such material.” They continue to rely on the limited data in journal articles and other published literature, says Herder of Dalhousie University.

“Transparency is wonderful in theory but unless people actually do the work of getting data and independently analyzing it, transparency is window dressing,” he says.

Barbara Mantel is a New York-based reporter who writes about health care and other social issues.

This story was produced by Undark, a nonprofit, editorially independent digital magazine exploring the intersection of science and society.

A woman rolls tobacco inside a tendu leaf to make a beedi cigarette at her home in Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh, India, on Wednesday, June 3, 2015. India’s smokers favor cheaper options such as chewing and leaf-wrapped tobacco over cigarettes.

Udit Kulshrestha/Bloomberg/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Udit Kulshrestha/Bloomberg/Getty Images

At a tiny kiosk on a Mumbai lane choked with rickshaws, Chandrabhaan Chaurasia is selling paan – betel leaves sprinkled with spices. They’re a cheap street snack across South Asia.

Chaurasia, 51, spreads a leaf with spicy herbal paste and then sprinkles it with dried tobacco. He folds the leaf into an edible little parcel, and sells it for 8 rupees — about $0.11. He also sells single-serving packs of chewing tobacco. Another kiosk nearby sells hand-rolled leaf cigarettes, called beedis.

India banned electronic cigarettes last month. With about 100 million smokers, India has the second-largest smoking population in the world, after China. Amid global reports of deaths and illnesses linked to vaping, India decided to ban e-cigarettes preventatively. They had yet to become popular.

But other forms of tobacco already are. In fact, twice as many Indians (about 200 million) use smokeless tobacco — like paan or chewing tobacco — than cigarettes. That’s the most in the world. Those products are harder to regulate because they’re mostly sold at street kiosks, for a fraction of the price of cigarettes.

Chaurasia’s tobacco kiosk is right outside Tata Memorial Hospital, one of the best cancer research facilities in India. Inside the hospital, Dr. Gauravi Mishra, a preventative oncologist, sees the harmful effects of those tobacco products on a daily basis.

“India has the highest number of oral cavity cancers. In fact, one-third of the global burden comes from only one country — and that’s India,” Mishra notes.

When NPR visited her office, Mishra had just biopsied a boil inside the mouth of a patient who’s been chewing tobacco for 10 years.

“I had some idea that it was bad, but I didn’t know it could be so serious,” says Madhukar Patil, 42, his mouth filled with sterile gauze.

Patil is waiting for results to determine whether he has oral cancer. A father of two, he vows to quit tobacco now, for good.

“I realize now that if you want to be there for your family and enjoy precious moments with them, then you must leave this bad habit,” Patil says.

More than one in five Indians over the age of 15 uses some form of smokeless tobacco. (The figure is nearly one-third for men.) Poor laborers often chew tobacco as a stimulant, like chewing gum, to kill their appetite. Some even use tobacco ash as toothpaste. Patil used to chew gutka, a mixture of granular tobacco, betel nuts and spices.

Part of the problem is awareness.

“If someone is smoking, they might be looked down upon. But smokeless tobacco is culturally accepted. If you visit any rural area, people will greet you with paan,” Mishra says.

Another part of the problem is packaging.

Indian law requires cigarette companies to print health warnings on cigarette packs. Often, they carry graphic photos of tobacco-related tumors. So people know that smoking cigarettes is bad.

But other tobacco products are sold loose. Hand-rolled leaf cigarettes, or beedis, are green. They look organic. And they’re seven to eight times more common in India than conventional cigarettes, according to the World Health Organization.

Beedis also provide a livelihood to millions of mostly female, first-time workers.

Balamani Sherla, 60, rolls beedis (leaf cigarettes) in her one-room home in Mumbai’s red light district. It’s the only job she’s ever had, and she’s been doing it for 50 years. She breathes tobacco dust all day, and earns about 14 cents an hour.

Sushmita Pathak/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Sushmita Pathak/NPR

In Mumbai’s oldest red light district, Balamani Sherla rolls beedis on the floor of her one-room home. At 60, Sherla has been doing this for half a century. It’s the only job she’s ever held.

She buys the ingredients wholesale: tendu leaves, dried loose tobacco, and string to tie off the rolled beedis. Sherla soaks the leaves in water to soften them, then cuts them round with giant shears, lines them with tobacco, and rolls them into short green cigarettes. She sells them to a middle man who then distributes them to street kiosks.

“It’s tedious work,” she says. “My arms ache, trying to roll the beedis very thin.”

Sherla doesn’t smoke. But studies show that beedi rollers often suffer from respiratory problems, burning eyes and asthma – just from breathing tobacco dust.

Nevertheless, it’s considered such a lucrative skill that women who can roll beedis are coveted as brides. Sherla makes about $0.14 an hour, which is a big help for her family, she says.

But wages used to be higher. The Indian government has repeatedly hiked tax on all tobacco products, including beedis — and that has cut into Sherla’s profits.

Most of the revenue India collects from taxing tobacco comes from packaged cigarettes, even though they’re less popular than beedis and smokeless tobacco. Tax rates on all tobacco products in India fall below the WHO’s recommendation of 75-percent of retail price.

Levying taxes on tobacco has long been considered an effective strategy to discourage its use and improve public health. But in India, where beedi workers often come from very low socio-economic backgrounds, that tax itself could be deadly, says Umesh Vishwad, general secretary of the Akhil Bharatiya Beedi Mazdoor Mahasangh (All India Beedi Workers Union).

If taxes on beedis keep rising, workers could “become homeless and starve to death,” Vishwad says.

They live that close to the bone, he says. His group wants the Indian government to retrain beedi workers for other jobs, before it chips away at their livelihood.

While Sherla and some of her neighbors roll beedis at home in urban Mumbai, the industry employs more people in rural areas, especially in the southern Indian states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. In central India, some of the beedi workers come from tribal areas where communist guerrillas are active. Vishwad worries that if their livelihoods are threatened, they could be vulnerable to insurgent recruiters.

“If these people lose their jobs as beedi rollers or beedi leaf collectors, they could be forced to join the militancy and pick up arms to survive,” he warns.

For Sherla, rolling beedis is a calculated decision. She knows that handling tobacco may not be good for her health. But she’s trading a long-term health risk for the ability to feed her family tomorrow.

“What other job can I do? I’m an old lady,” Sherla says. “This is the only option for me.”

As she works, Sherla’s 10-year-old granddaughter Siri bounces around the dank little room. The girl goes to school, and has learned English well. She interrupts often to tease her grandmother and translate for her. She’s the same age Sherla was when she started doing this work.

Will Siri follow in her grandmother’s footsteps?

“No way!” Sherla exclaims. “This little girl wants to be a doctor.”