Some Parts Of Trump’s Executive Order On Medicare Could Lead To Higher Costs

President Trump signed an executive order requiring changes to Medicare on October 3. The order included some ideas that could raise costs for seniors, depending how they’re implemented.

SOPA Images/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Gett

hide caption

toggle caption

SOPA Images/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Gett

Vowing to protect Medicare with “every ounce of strength,” President Donald Trump last week spoke to a cheering crowd in Florida. But his executive order released shortly afterward includes provisions that could significantly alter key pillars of the program by making it easier for beneficiaries and doctors to opt out.

The bottom line: The proposed changes might make it a bit simpler to find a doctor who takes new Medicare patients, but it could lead to higher costs for seniors and potentially expose some to surprise medical bills, a problem from which Medicare has traditionally protected consumers.

“Unless these policies are thought through very carefully, the potential for really bad unintended consequences is front and center,” says economist Stephen Zuckerman, vice president for health policy at the Urban Institute.

While the executive order spells out few details, it calls for the removal of “unnecessary barriers” to private contracting, which allows patients and doctors to negotiate their own deals outside of Medicare. It’s an approach long supported by some conservatives, but critics fear it would lead to higher costs for patients. The order also seeks to ease rules that affect beneficiaries who want to opt out of the hospital portion of Medicare, known as Part A.

Both ideas have a long history, with proponents and opponents duking it out since at least 1997, even spawning a tongue-in-cheek legislative proposal that year titled, in part, the “Buck Naked Act.” More on that later.

“For a long time, people who don’t want or don’t like the idea of social insurance have been trying to find ways to opt out of Medicare and doctors have been trying to find a way to opt out of Medicare payment,” says Timothy Jost, emeritus professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law in Virginia.

The specifics will not emerge until the Department of Health and Human Services writes the rules to implement the executive order, which could take six months or longer. In the meantime, here are a few things you should know about the possible Medicare changes.

What are the current rules about what doctors can charge in Medicare?

Right now, the vast majority of physicians agree to accept what Medicare pays them and not charge patients for the rest of the bill, a practice known as balance billing. Physicians (and hospitals) have complained that Medicare doesn’t pay enough, but most participate anyway. Still, there is wiggle room.

Medicare limits balance billing. Physicians can charge patients the difference between their bill and what Medicare allows, but those charges are limited to 9.25% above Medicare’s regular rates. But partly because of the paperwork hassles for all involved, only a small percentage of doctors choose this option.

Alternatively, physicians can “opt out” of Medicare and charge whatever they want. But they can’t change their mind and try to get Medicare payments again for at least two years. Fewer than 1% of the nation’s physicians have currently opted out.

What would the executive order change?

That’s hard to know.

“It could mean a lot of things,” says Joseph Antos at the American Enterprise Institute, including possibly letting seniors make a contract with an individual doctor or buy into something that isn’t traditional Medicare or the current private Medicare Advantage program. “Exactly what that looks like is not so obvious.”

Others say eventual rules might result in lifting the 9.25% cap on the amount doctors can balance-bill some patients. Or the rules around fully “opting out” of Medicare might ease so physicians would not have to divorce themselves from the program or could stay in for some patients, but not others. That could leave some patients liable for the entire bill, which might lead to confusion among Medicare beneficiaries, critics of such a plan suggest.

The result may be that “it opens the door to surprise medical billing if people sign a contract with a doctor without realizing what they’re doing,” says Jost.

Would patients get a bigger choice in physicians?

Proponents say allowing for more private contracts between patients and doctors would encourage doctors to accept more Medicare patients, partly because they could get higher payments. That was one argument made by supporters of several House and Senate bills in 2015 that included direct-contracting provisions. All failed, as did an earlier effort in the late 1990s backed by then-Sen. Jon Kyl, R-Ariz., who argued such contracting would give seniors more freedom to select doctors.

Then-Rep. Pete Stark, D-Calif., opposed such direct contracting, arguing that patients had less power in negotiations than doctors. To make that point, he introduced the “No Private Contracts To Be Negotiated When the Patient Is Buck Naked Act of 1997.”

The bill was designed to illustrate how uneven the playing field is by prohibiting the discussion of or signing of private contracts at any time when “the patient is buck naked and the doctor is fully clothed (and conversely, to protect the rights of doctors, when the patient is fully clothed and the doctor is naked).” It, too, failed to pass.

Still, the current executive order might help counter a trend that “more physicians today are not taking new Medicare patients,” says Robert Moffit, a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C.

It also might encourage boutique practices that operate outside of Medicare and are accessible primarily to the wealthy, says David Lipschutz, associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy.

“It is both a gift to the industry and to those beneficiaries who are well off,” he says. “It has questionable utility to the rest of us.”

KHN is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Lawmakers Seek Protections For Workers Against Lung Damage Tied To Making Countertops

A colored X-ray of the lungs of a patient with silicosis, a type of pneumoconiosis. The yellow grainy masses in the lungs are areas of scarred tissue and inflammation.

CNRI/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

CNRI/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

Lawmakers in Congress are calling on the Department of Labor to do more to protect workers who may be unsafely cutting “engineered stone” used for countertops.

The material contains high levels of the mineral silica, and breathing in silica dust is dangerous. While silica is found in natural stones, like granite, engineered stone made of quartz can be more than 90% silica.

This type of artificial stone has become increasingly popular among Americans for kitchen and bathroom countertops in recent years.

Even though adequate dust control can completely eliminate the risk of silica-related disease, at least 18 workers in California, Colorado, Texas and Washington who cut slabs of this material to order have recently suffered severe lung damage, according to physicians and public health officials.

Two of the workers died of their silicosis, a lung disease that can be progressive and has no treatment except for lung transplant. That has occupational safety experts worried about the nearly 100,000 people who work in this industry.

And it’s gotten the attention of the House Committee on Education and Labor. Its chairman, Bobby Scott, and Alma Adams, who chairs a subcommittee on workforce protections, have now written to Labor Department Secretary Eugene Scalia.

The lawmakers say the department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration needs to create a new National Emphasis Program that will make it easier to for the agency to inspect workplaces that cut engineered stone, to make sure levels of silica dust are within allowable limits.

“We are calling on OSHA to issue, without delay, a new NEP that focuses on engineered stone fabrication establishments,” the lawmakers write. “Absent timely action, OSHA will be failing these stone finishing workers and failing in its mission.”

Without this new program, they say, “it is difficult for OSHA to enter a workplace without a worker complaint, injury, or referral.”

The two lawmakers also call on OSHA to work with the CDC and state health departments to improve surveillance for silica-related diseases. They say they want an update on the plans to protect workers in the engineered stone fabrication industry by Oct. 21.

A trade organization for makers of engineered stone, A.St.A. World-Wide, has told NPR that “these risks are not specific to engineered stone” and that dust related diseases “preceded the invention of engineered stone by many decades.”

The group said engineered stone surfaces “are totally safe in their fabrication and installation if it is performed according to the recommended practices,” and that manufacturers have been working to educate fabricators about these practices.

Phone Scammers And ‘Teledoctors’ Charged With Preying On Seniors In Fraud Case

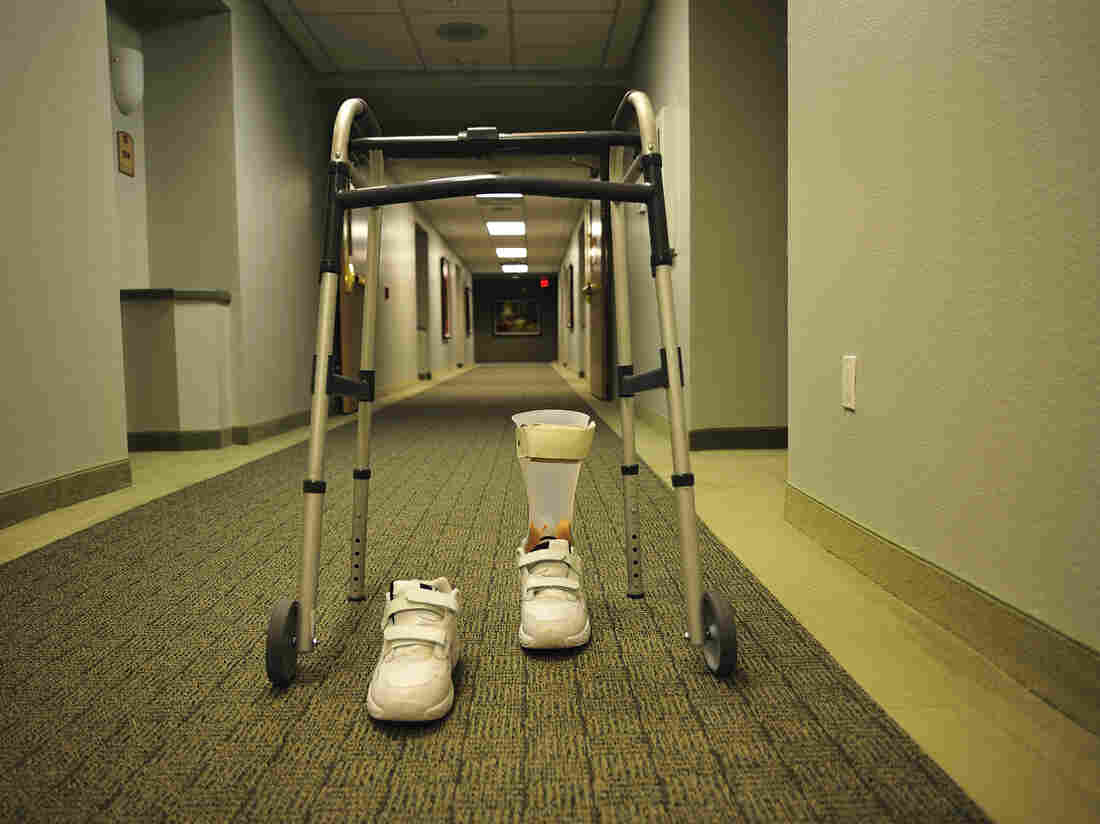

While prescriptions for durable medical equipment, such as orthotic braces or wheelchairs, have long been a staple of Medicare fraud schemes, some alleged scammers are now using telemedicine and unscrupulous health providers to prescribe unneeded equipment to distant patients.

Joelle Sedlmeyer/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Joelle Sedlmeyer/Getty Images

Dean Ernest had been living in a nursing home about a year when his son, John, got a call last winter asking if his father was experiencing back pain and would like a free orthotic brace.

The caller said he was with Medicare. John Ernest didn’t believe him, said “no” to the brace and hung up. He didn’t give out his father’s Medicare number.

And yet, not just one, but 13 braces addressed to Dean arrived soon afterward at the younger Ernest’s house in central Pennsylvania — none of which Dean Ernest wanted or needed.

Telemedicine scams on the rise

Medicare, the federal, taxpayer-supported health care insurance program for older Americans, had paid more than $4,000 for 10 of the braces: a back brace, two knee braces, two arm braces, two suspension sleeves, an ankle brace, a wrist brace and a heel stabilizer — none of which Dean Ernest wanted or needed..

The orders came from four different medical equipment companies and were prescribed by four health care professionals —a prescription is required to receive an orthotic brace. But John Ernest says he didn’t talk to any doctors during the phone call.

That’s how the latest Medicare frauds work, says Ariel Rabinovic, who works with Pennsylvania’s Center for Advocacy for the Rights & Interests of the Elderly. He helped report the Ernests’ fraud case to authorities at Medicare. Rabinovic said the fraudsters enlist unscrupulous health professionals ?doctors, physician assistants, nurse practitioners ? to contact people they’ve never met by telephone or video chat under the guise of a telemedicine consultation.

“Sometimes the teledoctors will come on the line and ask real Mickey Mouse questions, stuff like, “Do you have any pain?” explained Rabinovic. “But oftentimes, there is no contact between the doctor and the patient before they get the braces. And in almost all of the cases, the person prescribing the braces is somebody the Medicare beneficiaries don’t know.”

While prescriptions for durable medical equipment, such as orthotic braces or wheelchairs, have long been a staple of Medicare fraud schemes, the manipulation of telemedicine is relatively new. The practice appears to be increasing as the telemedicine industry grows.

“This has put telemedicine scams on Medicare’s radar with growing urgency,” says James Quiggle, director of communications for the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud.

In the past year, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, the Department of Justice and, in some cases, the FBI, have busted at least six health care fraud schemes that involved telemedicine. Typically, in these schemes, scammers use sham telemedicine companies to scale up their operations quickly and cheaply, because they can have a couple of doctors remotely writing a large number of prescriptions.

Often the doctors working for these outfits don’t perform medical consultations, but rather write prescriptions without talking to patients, as in Ernest’s case. Of course, that is not how telemedicine is designed to work.

International fraud

In April 2019, the DOJ announced investigators had disrupted what they called “one of the largest Medicare fraud schemes in U.S. history.” “Operation Brace Yourself” cracked an international scheme allegedly defrauding Medicare of more than $1.2 billion by using telemedicine doctors to prescribe unnecessary back, shoulder, wrist and knee braces to beneficiaries.

The DOJ charged 24 people, including three medical professionals and the corporate executives of five telemedicine companies.

According to federal court documents, Willie McNeal of Spring Hill, Fla., owned two of the “purported” telemedicine companies, WebDoctors Plus and Integrated Support Plus.

Federal investigators allege that through Integrated Support Plus, McNeal hired and paid a New Jersey doctor, Joseph DeCorso, to write prescriptions for braces. DeCorso recently pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit health care fraud.

DeCorso admitted to writing medically unnecessary brace orders for telemedicine companies without speaking to beneficiaries or doing physical exams. He also admitted that his conduct resulted in a $13 million loss to Medicare. He has agreed to pay more than $7 million in restitution to the federal government.

McNeal got the Medicare beneficiaries’ information for DeCorso to write the prescriptions from telemarketing companies, according to the indictment. Then, authorities allege, McNeal sent the prescriptions back to the same telemarketing companies in exchange for payments described as kickbacks and bribes.

Federal investigators allege these telemarketing companies sold the prescriptions to the durable medical equipment companies, who, as part of the scheme, fraudulently billed Medicare for the braces.

McNeal’s lawyer says he can’t discuss his client’s case for this story because of the pending lawsuit. DeCorso’s lawyer did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The U.S. attorneys allege the money made from the scheme was hidden through international shell corporations and used to buy luxury real estate, exotic automobiles and yachts.

Taxpayers on the hook for millions

It’s clearly a profitable business. Taxpayers are the ones who ultimately pay for Medicare fraud, which often leads to higher health care premiums and higher out-of-pocket costs.

Medicare spending on the sorts of braces highlighted in the inspector general’s investigations increased by more than $200 million from 2013 to 2017, according to an analysis of Medicare data by Kaiser Health News. While the number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries increased only slightly (by 5%) from 2013 to 2017, spending on the three types of braces increased by 51% during that same period.

In an April news release about Operation Brace Yourself, Assistant Attorney General Brian Benczkowski, of the DOJ’s Criminal Division, called the Medicare scheme “an expansive and sophisticated fraud to exploit telemedicine technology meant for patients otherwise unable to access health care.”

Nathaniel Lacktman, a lawyer who represents telemedicine companies and organizations, was quick to point out that the industry does not recognize the fraudsters involved in these schemes as legitimate businesses.

“These are actually really sketchy online marketing companies participating in these schemes, who are billing themselves as telemedicine,” says Lacktman, who works in the Tampa office of the law firm Foley & Lardner. “But in fact, they’re companies we’ve never heard of.”

All of this comes at a time when Medicare and Medicare Advantage are expanding their use of telemedicine, though the federal programs have been slower to adopt the practice than the private sector, says Laura Laemmle-Weidenfeld, a health care lawyer at the law firm Jones Day.

“I would hate for Medicare to fall even further behind with telehealth,” says Laemmle-Weidenfeld, who previously worked in the Fraud Section of the DOJ’s Civil Division. “The vast majority of telehealth providers are legitimate but, as with anything, there are a few bad apples.”

Even with the recent federal busts, the scams continue. And they’re not isolated to durable medical equipment. A $2.1 billion scheme was busted by the DOJ in September which involved telemedicine doctors authorizing unnecessary genetic tests.

Travis Trumitch, who works for the Illinois nonprofit AgeOptions, which helps report Medicare fraud in the state, says he received three voicemails over a recent weekend reporting suspected durable medical equipment scams.

John Ernest says he still receives calls every day with individuals on the line who say they work for Medicare and ask for Dean Ernest’s information ? though his father died in April.

But Ernest can’t change his phone number, because it’s the main line associated with his painting business.

“It really drives me crazy,” Ernest says. “How many people are they ripping off?”

Kaiser Health News data editor Elizabeth Lucas contributed to this report.

KHN is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Illinois Lawmaker Discusses New Planned Parenthood Facility

NPR’s Michel Martin speaks with Illinois State Rep. Katie Stuart about a secret Planned Parenthood built in her district that will expand reproductive health services in the area.

How Immigrants Use Health Care

NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro talks with Anne Dunkelberg of the Center for Children and Families about the new rule denying visas to immigrants without health insurance or funds to pay for health care.

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

President Trump has announced another new immigration rule set to take effect next month, though it’s likely headed to federal court. The rule would require foreign nationals to prove they have health insurance or the money to pay for their own health care costs before they can legally enter the United States. Simply put – no proof, no visa. The president said this action is necessary to, quote, “protect the availability of health care benefits for Americans.”

We wanted to get a better understanding of how immigrants use and pay for health care in the United States. Anne Dunkelberg is an associate director of the Center for Public Policy Priorities in Austin, Texas. She’s spent her career working on health care access issues, and she joins us now.

Welcome.

ANNE DUNKELBERG: Good morning.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: How would this work? I mean, if you’re a visitor and you’re traveling, you would obviously get travel insurance, which isn’t terribly expensive. If you are coming to immigrate, then what would you have to show?

DUNKELBERG: It’s a great question that we probably can’t answer. It sounds to me like, you know, it could conceivably require the creation of a whole new segment of the health insurance industry that’s just designed to answer this new requirement for even visiting the United States.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: The other thing that confuses me a little bit about this is this seems like an additional step that – already, when you apply for a visa outside of the United States, you do have to prove some sort of financial stability.

DUNKELBERG: You’re absolutely right. Even for these short-term visitor-type visas, there’s already screening to try to detect people who might be coming here without means and likely to, for example, overstay their visa.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Getting insurance in this country is complicated for Americans. It is even more complicated if you’re coming into this country. And presumably, if you have a work visa and you’re being sponsored by someone, you would have insurance already. So it’s unclear, a little bit, who this is targeting exactly.

DUNKELBERG: It sounds, frankly, more like the intention is for the optics of the policy as much as it is, you know, having a practical system in place to do it. If you read the document that was announced, you find that it actually outlines many of the other things that the Trump administration has either proposed or is in the process of trying to pursue. So they’ve presented it in their own document as part of what advocates for immigrants refer to as the invisible wall.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Your state, Texas, has one of the highest number of uninsured people in the U.S. So are the people who are uninsured Americans, or is the bigger portion people who are immigrants?

DUNKELBERG: Seventy-five percent, at least, of our uninsured are U.S. citizens. And then maybe another half a million are lawfully present immigrants. Some of the barriers to coverage that both U.S. citizens and lawfully present immigrants face, you know, are things that are well within the authority of our legislature and our governor to address. And obviously, some of the shortcomings of the Affordable Care Act that have left some Americans still unable to afford coverage are squarely in the lap of the U.S. Congress.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: So when the president says that uninsured individuals who are immigrants are a burden on the health care system, that is not the main cause of the burden of the uninsured. Most of that is citizens, so he is actually incorrect.

DUNKELBERG: Absolutely. The vast majority of uninsured Americans are U.S. citizens. That is the big challenge we have. We are obviously way more complicated here, and we’re looking to make it even more complicated for people to visit the United States, potentially more expensive, and thereby discourage particularly people who are not of means from visiting the United States.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That was Anne Dunkelberg of the Center for Public Policy Priorities in Austin, Texas. Thank you so much.

DUNKELBERG: Thank you, Lulu.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Targeting ‘Medicare For All’ Proposals, Trump Lays Out His Vision For Medicare

President Trump greets supporters after arriving at Florida’s Ocala International Airport on Thursday to give a speech on health care at The Villages retirement community. In his speech, Trump gave seniors a pep talk about what he wants to do for Medicare, contrasting it with plans of his Democratic rivals.

Evan Vucci/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Evan Vucci/AP

Updated at 4:30 p.m. ET

President Trump gave a speech and signed an executive order on health care Thursday, casting the “Medicare for All” proposals from his Democratic rivals as harmful to seniors.

His speech, which had been billed as a policy discussion, had the tone of a campaign rally. Trump spoke from The Villages, a huge retirement community in Florida outside Orlando, a deep-red part of a key swing state.

His speech was marked by cheers, standing ovations and intermittent chants of “four more years” by an audience of mostly seniors.

Trump spoke extensively about his administration’s health care achievements and goals, as well as the health policy proposals of Democratic presidential candidates, which he characterized as socialism.

The executive order he signed had previously been titled “Protecting Medicare From Socialist Destruction” on the White House schedule but has since been renamed “Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors.”

“In my campaign for president, I made you a sacred pledge that I would strengthen, protect and defend Medicare for all of our senior citizens,” Trump told the audience. “Today I’ll sign a very historic executive order that does exactly that — we are making your Medicare even better, and … it will never be taken away from you. We’re not letting anyone get close.”

The order is intended, in part, to shore up Medicare Advantage, an alternative to traditional Medicare that’s administered by private insurers. That program has been growing in popularity, and this year, premiums are down and plan choices are up.

The executive order directs the Department of Health and Human Services to develop proposals to improve several aspects of Medicare, including expanding plan options for seniors, encouraging innovative plan designs and payment models and improving the enrollment process to make it easier for seniors to choose plans.

The order includes a grab bag of proposals, including removing regulations “that create inefficiencies or otherwise undermine patient outcomes”; combating waste, fraud and abuse in the program; and streamlining access to “innovative products” such as new treatments and medical devices.

The president outlined very little specific policy in his speech in Florida. Instead, he attacked Democratic rivals and portrayed their proposals as threatening to seniors.

“Leading Democrats have pledged to give free health care to illegal immigrants,” Trump said, referring to a moment from the first Democratic presidential debate in which all the candidates onstage raised their hands in support of health care for undocumented migrants. “I will never allow these politicians to steal your health care and give it away to illegal aliens.”

Health care is a major issue for voters and is one that has dominated the presidential campaign on the Democratic side. In the most recent debate, candidates spent the first hour hashing out and defending various health care proposals and visions. The major divide is between a Medicare for All system — supported by only two candidates, Sen. Bernie Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren — and a public option supported by the rest of the field.

Trump brushed those distinctions aside. “Every major Democrat in Washington has backed a massive government health care takeover that would totally obliterate Medicare,” he said. “These Democratic policy proposals … may go by different names, whether it’s single payer or the so-called public option, but they’re all based on the totally same terrible idea: They want to raid Medicare to fund a thing called socialism.”

Toward the end of the speech, he highlighted efforts that his administration has made to lower drug prices and then suggested that drugmakers were helping with the impeachment inquiry in the House of Representatives. “They’re very powerful,” Trump said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if … it was from some of these industries, like pharmaceuticals, that we take on.”

Drawing battle lines through Medicare may be a savvy campaign move on Trump’s part.

Medicare is extremely popular. People who have it like it, and people who don’t have it think it’s a good thing too. A recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that more than 8 in 10 Democrats, independents and Republicans think of Medicare favorably.

Trump came into office promising to dismantle the Affordable Care Act and replace it with something better. Those efforts failed, and the administration has struggled to get substantive policy changes on health care.

On Thursday, administration officials emphasized a number of its recent health care policy moves.

“[Trump’s] vision for a healthier America is much wider than a narrow focus on the Affordable Care Act,” said Joe Grogan, director of the White House’s Domestic Policy Council, at a press briefing earlier.

The secretary of health and human services, Alex Azar, said at that briefing that this was “the most comprehensive vision for health care that I can recall any president putting forth.”

He highlighted a range of actions that the administration has taken, from a push on price transparency in health care, to a plan to end the HIV epidemic, to more generic-drug approvals. Azar described these things as part of a framework to make health care more affordable, deliver better value and tackle “impassable health challenges.”

Without a big health care reform bill, the administration is positioning itself as a protector of what exists now — particularly Medicare.

“Today’s executive order particularly reflects the importance the president places on protecting what worked in our system and fixing what’s broken,” Azar said. “Sixty million Americans are on traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage. They like what they have, so the president is going to protect it.”

‘Los Angeles Times’ Investigation Shows How Vaping Crisis Could Have Been Prevented

NPR’s Michel Martin speaks with Los Angeles Times reporter Emily Baumgaertner about how the FDA tried banning vaping flavors, but the Obama administration rejected it.

Judge Rules Planned Supervised Injection Site Does Not Violate Federal Drug Law

Attorney Ilana Eisenstein representing the nonprofit group Safehouse, recently spoke to the media about the legal fight with the Justice Department over a proposed supervised injection site. A federal judge on Wednesday declared that the plan does not violate U.S. drug law.

Matt Rourke/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Matt Rourke/AP

Updated at 3:30 p.m. ET

A judge has ruled that a Philadelphia nonprofit group’s plan to open the first site in the U.S. where people can use illegal opioids under medical supervision does not violate federal drug laws, delivering a major blow to Justice Department lawyers who have been working to block the facility.

U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh ruled Wednesday that Safehouse’s plan to allow people to bring in their own drugs and use them in a medical facility to help combat fatal overdoses does not violate the Controlled Substances Act.

“The ultimate goal of Safehouse’s proposed operation is to reduce drug use, not facilitate it,” McHugh wrote in his opinion.

The decision means that America’s first supervised injection site, or what advocates call an “overdose prevention site,” can go forward. Justice Department prosecutors had sued to block the site, calling the proposal “in-your-face illegal activity.”

Ronda Goldfein, who is Safehouse’s vice president and secretary, said winning judicial approval is a major feat for advocates of the proposed site, which also has the backing of top city officials.

“Philadelphia is being devastated. We’ve lost about three people a day” to opioid overdoses, Goldfein said. “And we say we had to do something better and we couldn’t sit back and let that death toll rise. And the court agreed with us.”

Similar facilities exist in Canada and Europe, but no such site has gotten legal permission to open in the U.S. Cities like New York, Denver and Seattle have been publicly debating similar proposals, but many were waiting for the outcome of the court battle in Philadelphia.

Prosecutors had contended that the plan violated a provision of the Controlled Substances Act that makes it illegal to own a property where drugs are being used — known as “the crack house statute.” But backers of Safehouse argued the law was outdated and not written to prevent the opening of a medical facility aimed at saving lives in the midst of the opioid crisis.

“We have consistently said we did not have an illegal purpose. We have a lawful purpose. Our purpose is to save lives,” Goldfein said.

On Wednesday, in a move that surprised observers, McHugh agreed.

“The statutory language that matters most is ‘purpose,’ and no credible argument can be made that a constructive lawful purpose is rendered predatory and unlawful simply because it moves indoors. Viewed objectively, what Safehouse proposes is far closer to the harm reduction strategies expressly endorsed by Congress,” McHugh wrote.

Sheriff’s Deputy Sues Her County To Get Health Coverage For Transgender-Related Care

Sgt. Anna Lange filed a lawsuit against the county where she works in Georgia for refusing to allow her health insurance plan to cover gender-affirmation surgery.

Audra Melton for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Audra Melton for NPR

A sheriff’s deputy in Perry, Ga., filed a lawsuit in federal court Wednesday against the county where she works for refusing to allow her health insurance plan to cover her gender-affirmation surgery.

Sgt. Anna Lange came out as transgender in 2017, after working in the Houston County Sheriff’s Office since 2006. She has taken hormone therapy and outwardly changed her appearance over the past three years to treat gender dysphoria, the distress resulting from the mismatch between her sex assigned at birth and her gender identity.

Her next step was going to be gender-affirmation surgery, but that plan came to a halt when, as NPR previously reported, her insurance provider denied coverage for the procedure, based on an exclusion specified by her employer.

Now, Lange is suing the Houston County Board of Commissioners to remove that exclusion. Early on Wednesday, she and her lawyer, Noah Lewis of the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund, filed suit in U.S. District Court in Macon, Ga., alleging unlawful discrimination under federal and state equal protection clauses, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

County officials did not return calls for comment.

Lange’s case is the latest in the U.S. to challenge the exclusion of transgender care from state and municipal employee insurance plans — and could create legal precedents for cases across the South.

Other transgender people have won similar fights elsewhere. The managers of Wisconsin’s state employee insurance program excluded transgender employees from coverage but later reversed that decision. Separately, two University of Wisconsin employees sued the state and won. Another lawsuit successfully challenged transgender exclusions in Wisconsin’s Medicaid plan.

Earlier this year, Jesse Vroegh, a transgender employee of the Iowa Department of Corrections, won a lawsuit he’d filed after being denied coverage by his employer’s health insurance plan.

And in Georgia, the state’s university system recently settled an insurance exclusion claim for gender-affirmation surgery filed by Skyler Jay, known for his appearance on the Netflix series Queer Eye. In addition to changing its employee health plan to be inclusive of transgender care, the university system paid Jay $100,000 in damages.

“The university clearly agreed that it was discrimination,” says Lange’s attorney, Lewis, who also represented Jay. “That’s why they wanted to do the right thing and remove the exclusion.”

In 2011, another Georgia case, Glenn v. Brumby, set the legal precedent protecting transgender people from employment discrimination. However, that case did not address discrimination in employee benefits and, like Jay’s case, many that deal with benefits have been settled out of court, according to Lewis.

The Affordable Care Act, which took effect in 2014, specifically prohibits discrimination by health insurance issuers on the basis of gender identity, and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act also has been interpreted to prohibit such discrimination.

Despite broad legal consensus that transgender insurance exclusions are unlawful, state and local governments continue to pursue expensive legal fights to preserve them. The issue remains contentious for many social conservatives.

“Ultimately, what’s happening is that, politically, I presume they think it’s unpopular or they think they have to defend” the law or regulation, says John Knight, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union.

Resisting paying for such care can be more expensive than providing it. Not including the costs of state attorneys’ salaries or appeals, Wisconsin’s litigation against the employees of its university system cost the state more than $845,000, while Iowa’s cost about $125,000.

Furthermore, the cost of managing untreated gender dysphoria can outweigh the costs of providing transgender-inclusive health care, according to a 2015 study.

“Given the small number of people who actually need this kind of care and the large pool of people, it will have absolutely no impact on the total cost of insurance for any state,” Knight says.

While settlements such as Jay’s may be good for individuals, they do not require institutions to admit wrongdoing and do not result in a legal precedent that other, lower courts must follow.

“The court doesn’t have to look at that settlement and say, ‘Oh, this was discrimination,’ ” Lewis says. “Transgender workers in the South are being left behind, which is why we’re seeking a court ruling to clearly establish that this conduct is unlawful throughout the South.”

Lange’s suit argues that the county’s exclusion of transgender health care from coverage was deliberate: In documents Lewis obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, Kenneth Carter, the county’s personnel director, opted out of compliance with Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, which prohibits discrimination by health programs on the basis of gender identity.

“Houston County will be responsible for any penalties that result if the plan is determined to be noncompliant,” he wrote in a letter to a representative of Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, which administers the plan.

Carter did not return calls for comment.

Lange’s case could end up before the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, yielding a decision that could influence other courts in Alabama, Florida and Georgia. And, if the ruling is in Lange’s favor, Lewis says, that would signal that transgender exclusions should be removed nationwide.

Lange’s suit argues that the county’s exclusion of transgender health care from coverage was deliberate.

Audra Melton for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Audra Melton for NPR

In its next term, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear three cases that will determine workplace protections of LGBTQ individuals, including one case involving a transgender woman.

Lange says she merely wants the same protections everyone else has. The co-workers with whom she shares a health plan might have used “something on the policy that I may never use or need, but it’s covered,” she says. “When it’s finally something that I need that one of my co-workers will probably never use or need, mine’s excluded. And that’s just not fair.”

Keren Landman, a practicing physician and writer based in Atlanta, covers topics in medicine and public health. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Workers Are Falling Ill, Even Dying, After Making Kitchen Countertops

A worker cuts black granite to make a countertop. Though granite, marble and “engineered stone” all can produce harmful silica dust when cut, ground or polished, the artificial stone typically contains much more silica, says a CDC researcher tracking cases of silicosis.

danishkhan/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

danishkhan/Getty Images

Artificial stone used to make kitchen and bathroom countertops has been linked to cases of death and irreversible lung injury in workers who cut, grind, and polish this increasingly popular material.

The fear is that thousands of workers in the United States who create countertops out of what’s known as “engineered stone” may be inhaling dangerous amounts of lung-damaging silica dust, because engineered stone is mostly made of the mineral silica.

Jose Martinez, 37, worked for years as a polisher and cutter for a countertop company that sold engineered stone, as well as natural stone like marble. He says dust from cutting the slabs to order was everywhere.

“If you go to the bathroom, it’s dust. When we go to take lunch, on the tables, it’s dust,” he says. “Your nose, your ears, your hair, all your body, your clothes — everything. When you walk out of the shop, you can see your steps on the floor, because of the dust.”

Now, he’s often weak and dizzy, and has pain in his chest — he can no longer play soccer or run around with his kids. Doctors have diagnosed silicosis, a lung disease that can be progressive and has no treatment except for lung transplant. Martinez is scared, after hearing that two other workers from the same company, who were also in their 30s, died of silicosis last year.

“When I go to sleep, I think about it every night — that if I’m going to die in three or four, five years?” he says, his voice breaking. “I have four kids, my wife. To be honest with you, every day I feel worse. Nothing is getting better.”

His experience is just one of those described in a new report on 18 cases of illness, including two deaths, among people who worked principally with engineered stone in California, Colorado, Texas and Washington.

The workers were nearly all Hispanic, almost all were men, and most had “severe, progressive disease.”

“I am concerned that what we may be seeing here may just be the tip of the iceberg,” says Dr. Amy Heinzerling, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who is assigned to the California Department of Public Health.

Engineered stone took off as a popular option for countertops about a decade ago, and is now one of the most common choices for kitchens and bathrooms. From 2010 to 2018, imports of the material rose around 800 percent.

Manufacturers say the material is preferable to natural stone because it’s less likely to crack or stain. Companies make their engineered stone by embedding bits of quartz in a resin binder, and that means it’s almost entirely composed of crystalline silica.

“Engineered stone typically contains over 90% silica,” says Heinzerling. “Granite, for instance, usually contains less than 45% silica. Marble usually contains less than 10%.”

While all this silica isn’t a concern once the countertop is installed in a kitchen or bathroom, it is a potential problem for the businesses that cut slabs of this artificial stone to the right shape for customers.

“Workers who cut with the stone can be exposed to much higher levels of silica,” says Heinzerling, “and I think we’re seeing more and more workers who are working with this material who are being put at risk.”

A spokesperson for a trade organization that represents major manufacturers of engineered stone, A.St.A. World-wide, sent NPR a written statement, noting that dust-related diseases can come from unsafe handling of many different materials and that “these risks are not specific to engineered stone.”

What’s more, the statement goes on, engineered stone surfaces “are totally safe in their fabrication and installation if it is performed according to the recommended practices.” Manufacturers, according to the trade group, have been working to educate fabricators about these practices.

Still, Heinzerling believes that “the fact that all of our affected workers worked with engineered stone, as did many of the workers reported internationally, is really important.”

One recent study in Australia found that at least 12% of workers who cut stone countertops had silicosis. Those cases, and the new cases in the United States, have public health experts now wondering about the nearly 100,000 U. S. workers in this industry.

Officials estimate that there are more than 8,000 stone fabrication businesses in the United States. Many are small-scale operations that might not understand the dangers of silica or how to control it.

Clusters of silicosis cases, some requiring lung transplants, had already occurred among workers who cut engineered stone in Israel, Italy, and Spain when doctors saw the first North American case in 2014.

That was a 37-year-old Hispanic man who had worked at a countertop company and had been exposed to dust, including dust from engineered stone, for around a decade.

More cases were then discovered in California when public health workers did a routine search of hospital discharge records for a diagnosis of silicosis. They identified a 38-year-old man who had died of silicosis in 2018 after working for a countertop manufacturer.

When they investigated his former workplace, they learned of another worker who had died of silicosis in 2018 at the age of 36. Four other workers from that same company, including Martinez, have been diagnosed with silicosis.

Meanwhile, in Colorado, an unusually high number of people with silicosis were showing up at the occupational health practice of Dr. Cecile Rose, professor of medicine at National Jewish Health and the University of Colorado.

“Over a period of less than 18 months, I had seen seven cases of silicosis in younger workers,” says Rose.

In the past, her patients with silicosis tended to be miners, who had dug for metals like gold and silver many years before. Her new patients were younger, and were working with companies that processed slabs of engineered and natural stone.

“We actually not only saw people who were directly cutting and grinding the stone, but we saw people who were just sweeping up the work site after the stone had been cut,” says Rose. “They were exposed to the silica particles that were suspended in the air just with housekeeping duties.”

More cases have been found in Texas. And in 2018, public health workers identified a 38-year old Hispanic man with silicosis in Washington who fabricated countertops. “He is facing serious health issues and is being considered for a lung transplant,” according to Washington State Department of Labor & Industries.

None of this surprises David Michaels, an epidemiologist at George Washington University who used to run OSHA, a safety agency within the Department of Labor. In 2015, he says, OSHA issued a “Hazard Alert” warning of a significant exposure risk for workers who manufacture natural and artificial stone countertops.

“We knew we’d see more cases,” says Michaels. “It’s disappointing that OSHA hasn’t done anything to stop these cases from occurring. These cases were predictable, and they were preventable.”

Prevention basically comes down to controlling the dust. Stone cutting businesses can choose from a variety of proven methods, ranging from working with stone while it’s wet to using vacuum or filtration systems that remove dust from the air.

In 2016, OSHA issued new workplace limits on how much silica could be in the air. This controversial new rule reduced the permissible exposure level to half of what it had been. Safety experts hailed the new, tighter limit as an important step forward; the previous regulations had been based on decades-old science, they said. But many industry groups opposed it.

A year later, the incoming Trump administration ended the safety agency’s national emphasis program for silica. That program would have allowed OSHA to target the countertop fabrication industry for special inspections, says Michaels.

“That way OSHA can have an impact on the entire industry,” says Michaels. “But OSHA is not doing that.”

Without that program, says Michaels, OSHA is limited in what it can legally do. OSHA can investigate a workplace injury or a complaint. But these workers, some of whom are undocumented immigrants with few employment options, are unlikely to complain.

A spokesperson for OSHA tells NPR that the agency will determine “at a later date” if a revised silica special emphasis program is needed; in the meantime the agency “continues to enforce the 2016 silica standard.”

“Employers are responsible for providing a safe and healthy workplace free from recognized hazards,” the spokesperson says.

Some countertop manufacturers are well aware of the dangers of silica. David Scott, the owner and operator of Slabworks of Montana, in Bozeman, estimates that about 40 to 50% of what he sells and cuts is the engineered stone.

He’s been able to dramatically reduce the amount of silica dust in his countertop fabrication shop over the last five years, he says.

One of his insurers provided testing for airborne silica, and Scott says levels were initially only marginally acceptable, even though his facility doesn’t do any dry processing of stone, which creates more dust. “We were a wet shop at that time, and we were still marginal,” he says.

Part of the problem was that water with silica dust would end up on the floor, he explains, and some of the water would evaporate before going down the drain.

“If you came in in the morning, you would see a white residue on our floor, and that was the dust,” says Scott. “So the first thing we did was bring in a floor scrubber. We call it our Zamboni.”

The machine scrubs and vacuums up the water, and Scott says that reduced the silica load in the air substantially. He then added new air handling systems to further remove dust. “We brought our silica levels, at times, down to undetectable,” says Scott.

He says consumers who want to make sure they’re buying a countertop from a responsible vendor can vet fabricators by looking to see if they are accredited by the Natural Stone Institute, which trains companies on how to safely cut and polish stone. Accreditation requires that companies to basically invite OSHA in to do an inspection.

But many operators, especially smaller ones, won’t have gone through this process. If a showroom is attached to a manufacturing stop, Scott says, a countertop buyer could simply look around.

“How much dust do you see? Because it gets everywhere,” says Scott. “General cleanliness is going to tell you a lot.”

In Australia, where government officials are grappling with a spike in aggressive cases of silicosis among workers who cut engineered stone, medical organizations are urging doctors to screen young workers to identify those who have lung disease.

Dr. Graeme Edwards, an occupational health physician in Brisbane, Queensland, says that currently there are more than 250 known cases of silicosis among people who manufacture countertops — or “benchtops,” as they are called in Australia.

Anyone who has worked with engineered stone for more than three years should have a high-resolution CT scan to check for lung injury, says Edwards, even if they don’t have any symptoms. He says this is especially true if they engaged in any dry-cutting of this material for more than a year, regardless of whether they used respiratory protection.

In an email, he says that American researchers’ assertion in their new report that, based on Australia’s experience, “there might be many more U. S. cases that have yet to be identified” is “a GROSS understatement.”

Jose Martinez, who is worried about his future, says he wants workers to know that the danger is real and that they have to protect themselves, because some companies may not care.

“At the end, it’s your family, it’s your health. It’s not about other people. It’s not about if your boss likes it or not,” says Martinez. “If you die, who is going to feed your kids? Who is going to take care of your family?”