NFL Suspends Myles Garrett ‘Indefinitely’ For Hitting QB With His Own Helmet

Cleveland Browns defensive end Myles Garrett hits Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Mason Rudolph with his own helmet as offensive guard David DeCastro tries to intervene, in the final seconds of their game Thursday night.

Ken Blaze/USA Today Sports / Reuters

hide caption

toggle caption

Ken Blaze/USA Today Sports / Reuters

Updated at 12:05 p.m. ET

The NFL has suspended Cleveland Browns defensive end Myles Garrett “indefinitely,” after Garrett ripped off Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Mason Rudolph’s helmet and whacked him in the head with it during a fight at the end of a game Thursday night.

Garrett won’t play again in the rest of 2019 and the postseason, the NFL announced. A date for his possible reinstatement and return won’t be set until he meets with the commissioner’s office.

“Garrett violated unnecessary roughness and unsportsmanlike conduct rules, as well as fighting, removing the helmet of an opponent and using the helmet as a weapon,” the NFL said as it announced its decision.

In response to the NFL’s move, Browns owners Dee and Jimmy Haslam sent a statement about Garrett to member station WCPN ideastream in Cleveland saying, “We understand the consequences from the league for his actions.”

The NFL also suspended Steelers center Maurkice Pouncey for three games for fighting: he punched and kicked Garrett in the aftermath of the helmet hit. And it punished the Browns’ Larry Ogunjobi with a one-game ban because he blindsided Rudolph with a hit after the quarterback had been separated from Garrett.

The league also fined all three players, but it did not disclose the amounts. The Browns and Steelers organizations were each fined $250,000.

The Haslams said they are “extremely disappointed” in the altercation. They added, “We sincerely apologize to Mason Rudolph and the Pittsburgh Steelers. Myles Garrett has been a good teammate and member of our organization and community for the last three years but his actions last night were completely unacceptable”

If Garrett’s suspension withstands an expected appeal, he would miss the Browns’ last six games. His punishment is one of the stiffest penalties for on-field behavior the NFL has ever levied, second only to that of Oakland Raiders linebacker Vontaze Burfict, who was suspended for the rest of the season in late September, with 12 games remaining.

The NFL says more disciplinary measures “will be forthcoming” for other players, including those who left their benches to join the fight.

Garrett’s actions obliterated the NFL’s boundaries of controlled violence, resulting in his immediate expulsion from Thursday night’s showcase game. The fighting also triggered shock and outrage and disbelief in the closing seconds of a game that the Browns’ defense had dominated.

YouTube

Garrett was ejected from the game along with Pouncey, who rushed in and helped take Garrett to the ground in retaliation for his attack on Rudolph. As lineman David DeCastro grappled with Garrett, Pouncey punched and kicked at his helmet. The Browns’ Ogunjobi was also ejected.

Discussing the fracas after the game, Garrett said it was “embarrassing and foolish and a bad representation of who we want to be.”

“Rivalry or not, we can’t do that. We’re endangering the other team. It’s inexcusable,” Browns quarterback Baker Mayfield said.

Garrett has emerged as a defensive star for Cleveland in his third professional year, but he has also incurred penalties at a fast rate, including two roughing-the-passer calls and an unsportsmanlike conduct foul before Thursday’s game.

The NFL has a personal safety rule forbidding “impermissible use of the helmet” — but the rulebook foresaw players using their own helmet to hit others in the course of a game, not a football player ripping an opponent’s helmet off and striking him with it.

“I made a mistake, I lost my cool,” Garrett said afterward. “And I regret it. It’s going to come back to hurt our team. The guys who jumped in the little scrum — I appreciate my team having my back, but it should never have gotten to that point. That’s on me.”

“I thought it was pretty cowardly, pretty bush league,” Rudolph said after the game. When asked how he was feeling after the violent end to a tough game, he replied, “I’m fine. I’m good, good to go.”

Before this season, the NFL’s longest suspension was a five-game ban earned by Albert Haynesworth in 2006 for removing a Dallas Cowboys player’s helmet and then stomping on his face.

After last night’s game, former Steelers linebacker James Harrison — who faced his own suspensions for dangerous hits during his career — was one of many NFL insiders who said Garrett’s actions amounted to assault.

“That’s assault at the least,” Harrison said via Twitter. He added, “6 months in jail on the street.. now add the weapon and that’s at least a year right?!”

The incident began with around 10 seconds left in the game: Garrett grabbed Rudolph as the quarterback completed a harmless third-down pass in the Steelers’ own end, stopping the game clock at 8 seconds. But after Garrett tugged and twisted Rudolph to the ground, the two began wrestling and Rudolph grasped Garrett’s helmet with both hands.

As they got up, Garrett ripped the quarterback’s helmet off by its facemask — and as DeCastro tried to intervene, Garrett swung Rudolph’s helmet in a vicious overhand arc, hitting the quarterback. As Rudolph turned to an official seeking a penalty, the Browns’ Ogunjobi leveled him from behind, sending him back down to the turf.

At the time, the Browns were leading 21-7, and their defense had already recorded four sacks and four interceptions against Rudolph’s Steelers. In the Browns’ stat sheet for the night, Garrett was notably absent from its sack list.

Going into Thursday night’s game, Garrett was leading the AFC in sacks, with 10 quarterback takedowns through the first nine games of the season. He had also been effective against the Steelers, recording four sacks and forcing three fumbles in just three games against the Browns’ division rivals.

Cleveland started the year on a wave of optimism, with talk of a possible run deep into the playoffs. But the team hasn’t lived up to those expectations. And now — instead of discussing their hopes to build on a win that brought their record to 4-6 — the Browns and Garrett are the talk of the NFL for all the worst reasons.

Prior to Garrett’s ejection, Browns safety Damarious Randall was also kicked out of Thursday night’s game, for delivering a dangerous helmet-to-helmet hit on Steelers wide receiver Diontae Johnson. But it was the end of the game that left the worst impressions in Cleveland.

“It feels like we lost,” Mayfield said afterward.

KOKOKO!: Tiny Desk Concert

Credit: Mhari Shaw/NPR

KOKOKO! are sonic warriors. They seized control of the Tiny Desk, shouting their arrival through a megaphone, while electronic sirens begin to blare. There’s a sense of danger in their sonic presence that left no doubt that something momentous was about to happen. And it did!

With instruments tied and hammered together — made from detergent bottles, scrapyard trash, tin cans, car parts, pots, pans and more — KOKOKO! managed to alter the office soundscape.

Backed by a bank of electronics, including a drum machine, this band from the Democratic Republic of the Congo redefines the norm of what music is and how music is made. Wearing yellow jumpsuits that are both utilitarian and resemble Congolese worker attire, this band from Kinshasa feel as though they’re venting frustrations through rhythm. And all the while they’re making dance music, all from their debut LP, Fongola, that feels unifying — more party than politics.

SET LIST

- “Likolo”

- “Tongos’a”

- “Malembe”

MUSICIANS

Boms Bomolo: bass, vocals; Dido Oweke: guitar; Makara N’zaku: drums, vocals; Love Lokombe: percussion, vocals; Xavier Thomas: keys, synthesizer, vocals;

CREDITS

Producers: Bob Boilen, Morgan Noelle Smith; Creative Director: Bob Boilen; Audio Engineers: Josh Rogosin, Alex Drewenskus ; Videographers: Morgan Noelle Smith, Jack Corbett, Bronson Arcuri, Maia Stern; Associate Producer: Bobby Carter; Executive Producer: Lauren Onkey; VP, Programming: Anya Grundmann; Photo: Ben De La Cruz/NPR

Why Even Universal Health Coverage Isn’t Enough

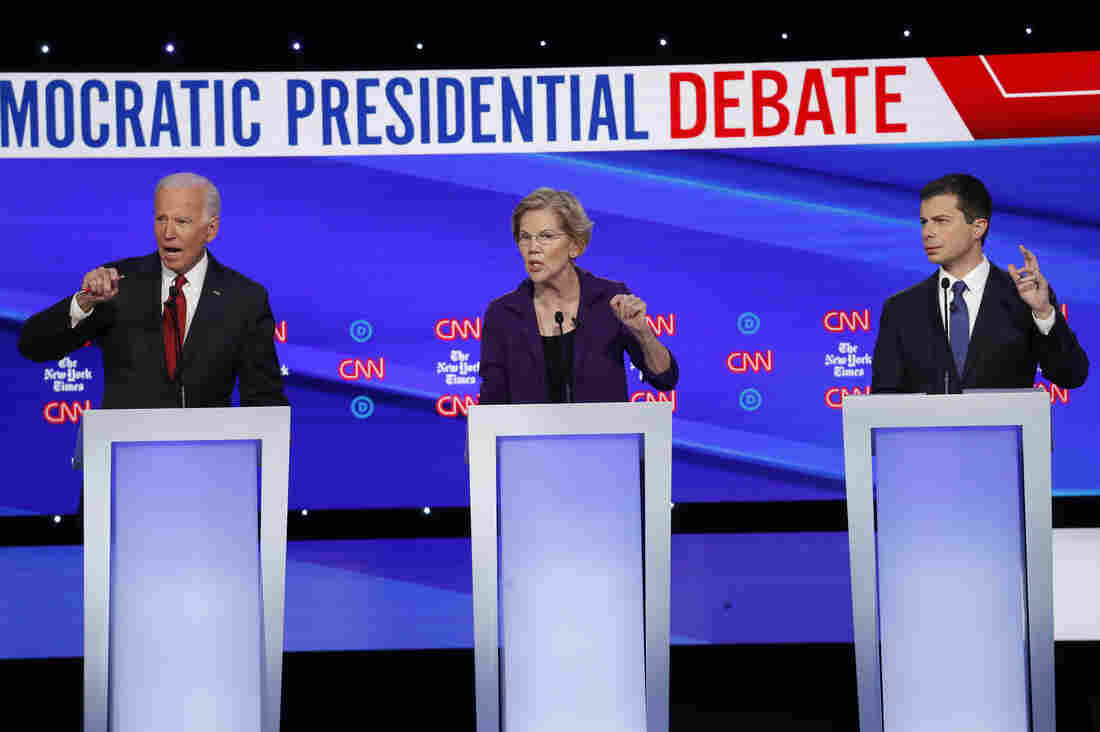

Democratic presidential candidates former Vice President Joe Biden (left), Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg (right) debate different ways to expand health coverage in America.

John Minchillo/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

John Minchillo/AP

The Democratic debate is less than a week away, and it’s likely that health care will once again take center stage. Once again, the candidates will spar over the best way to achieve universal coverage. Once again, the progressives will talk up the benefits of “Medicare For All” while the moderates attack it for its high cost and lack of choice. Just like the last debate. And the one before.

But it’s not the repetitiveness of the health care debate that bothers me. As a medical student, what bothers me is that the current health care debate is myopically focused on health insurance.

Although health insurance coverage is important, it’s only part of the picture. If the goal of our health care system is to keep Americans healthy, insurance will only get us so far. Health is about much more than access to health care.

Asthma triggers when you’re homeless

Take the case of a patient I helped treat this past summer, a young man in his early 20s who came into the emergency department experiencing severe shortness of breath. I could hear him wheezing before I even walked into the room.

He was sitting on the stretcher, breathing rapidly, and leaning forward with his hands on his knees — the classic “tripod” position signifying respiratory distress. After the resident physician and I determined he was having an asthma attack, we controlled his symptoms with steroids and inhalers and monitored him until he improved.

As I was preparing to discharge the patient, I briefed him on some of the asthma triggers he should avoid. When I advised him to keep the windows closed to minimize his exposure to pollen, he told me that the shelter where he was staying didn’t have air conditioning. It was 83 degrees outside that day.

Health insurance couldn’t prevent his next asthma attack. He needed a better and more stable housing situation.

Food deserts and no ride to the doctor

The same was true for a second patient of mine who was admitted to the hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of diabetes resulting from poor blood sugar control. After he recovered, we discharged him home to a food desert, a neighborhood where grocery stores and fresh-food markets are scarce and where following a low-carbohydrate diet is next to impossible. Health insurance cannot solve the food insecurity in his community.

Nor could health insurance enable a third patient of mine — who’d had vascular surgery to re-open a blocked artery in his leg — to return for his follow-up visit. Had he done so, we would have caught his post-operative infection early. As it happened, however, he had no way of traveling the 15 miles from his home to our clinic, and his infection worsened to the point that we had to amputate two of his toes. Health insurance didn’t address his transportation barriers.

Fortunately, all three patients were insured. Indeed, I’m grateful to attend medical school in Massachusetts, which has achieved near universal health insurance coverage. But sometimes insurance isn’t enough. I constantly see cases like these in which acute health problems arise due to factors seemingly unrelated to medicine. Universal coverage, while a worthy goal, does not translate into universal health.

Who will fix holes in the social safety net?

A recent study that rated U.S. counties based on health outcomes found that access to medical care accounted for only 20 percent of a county’s score. The other 80 percent was more readily attributable to social and economic factors like the ones affecting my patients, including housing instability, food insecurity, and access to transportation.

The health care dialogue in this political race has been dominated by the notion that we need to cover everyone, a principle I fully support. But even if we achieve that, it will only get us a fraction of the way to our goal of better health for all Americans. The German health care system is widely praised for its universal coverage, robust primary care, and low out-of-pocket costs for medical care. But it is nonetheless plagued with health disparities. In some cities, life expectancies of neighboring communities differ by up to 13 years.

To neglect these social factors in our public discourse on health care would be a mistake, not only because they are important to public health but also because policymakers are often better equipped to tackle social factors than they are medical ones. Evidence suggests that providing stable housing to homeless populations in urban areas, for instance, contributes to significantly reduced mortality.

Insurance coverage is a critical determinant of health. We should discuss it. But candidates for president should also discuss their plans to strengthen communities by addressing homelessness, food insecurity, and the other social factors that underpin America’s health gap.

Thus far, these issues have received scant attention in the Democratic primary race and in the larger political dialogue about health care. We need to broaden the conversation from a narrow discussion of health insurance to a holistic conversation about health.

Suhas Gondi is a third-year medical student at Harvard Medical School. A version of this essay originally appeared in Undark, the online science magazine.

Colin Kaepernick And The NFL

Sports writer Kevin Blackistone talks with Rachel Martin about the sincerity of Colin Kaepernick’s workout for the NFL.

How The Houston Astros Stole Signs In The 2017 Season

NPR’s Audie Cornish talks with Washington Post sports columnist Barry Svrluga about the system the 2017 Astros had for stealing signs, and how the Nationals prepped for it this year.

University Of Memphis Defies NCAA, Tests Enforcement Of Amateurism Rules

The University of Memphis is defying the NCAA and suiting up a star freshman who has been deemed “likely ineligible.” It’s a test of the NCAA’s power to enforce longstanding amateurism rules.

Colin Kaepernick Is Getting An NFL Workout. Skeptics Question League’s Timing

Colin Kaepernick was notified by the NFL on Tuesday taht he will have a private workout for NFL teams in Atlanta on Saturday. He last played an NFL snap during the 2016 season.

Charles Sykes/Charles Sykes/Invision/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Charles Sykes/Charles Sykes/Invision/AP

After nearly three years away from the game, Colin Kaepernick, the quarterback who became a lightning rod for taking a knee to protest social injustice during the national anthem, is one step closer to being back in the NFL.

Kapernick, a once-electrifying player who has a Super Bowl appearance on his resume, got notice from the NFL on Tuesday that a private workout has been arranged for him on Saturday in Atlanta.

All 32 NFL teams — those same teams that have refused to sign him following the anthem controversy — will be invited to the Atlanta Falcons facility in Flowery Branch, Ga.

The former Pro Bowl quarterback, who played with the San Francisco 49ers, last suited up for an NFL game during the 2016 season. Kaepernick appears to have been caught off guard by the league’s sudden interest, tweeting Tuesday evening:

“I’m just getting word from my representatives that the NFL league office reached out to them about a workout in Atlanta on Saturday. I’ve been in shape and ready for this for 3 years, can’t wait to see the head coaches and GMs on Saturday.”

I’m just getting word from my representatives that the NFL league office reached out to them about a workout in Atlanta on Saturday. I’ve been in shape and ready for this for 3 years, can’t wait to see the head coaches and GMs on Saturday.

— Colin Kaepernick (@Kaepernick7) November 13, 2019

The scheduled workout presents a long-awaited opportunity for Kaepernick to quiet doubters and show he can still play at an NFL level.

It also offers a chance to move past allegations he’s levied against the league that all 32 teams colluded to bar him from playing. Kaepernick and the league settled a grievance in February. A similar settlement was reached with Eric Reid, who knelt with Kaepernick during the Star Spangled Banner. Reid wasn’t immediately picked up when his contract expired but now plays safety for the Carolina Panthers.

From left, Eli Harold (58), Colin Kaepernick (7) and Eric Reid (35) kneel during the national anthem before their NFL game against the Dallas Cowboys on Sunday, Oct. 2, 2016.

San Jose Mercury News/Tribune News Service via Getty I

hide caption

toggle caption

San Jose Mercury News/Tribune News Service via Getty I

Then and now, Kaepernick maintains that the demonstration that began during a preseason game in 2016 was meant to call attention to police shootings of unarmed black people and inequality in the criminal justice system.

Critics, including then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, derided the displays of kneeling as disrespectful to U.S. troops and the American flag.

Before the start of the 2016 NFL season, Trump blasted Kaepernick and the protests, suggesting “maybe he should find a country that works better for him.” In 2017, the first season Kaepernick went unsigned, now-President Trump suggested that the NFL “fire or suspend” any player who didn’t stand for the national anthem.

The news of Saturday’s workout was first reported by ESPN, which adds that “several clubs” have put out feelers about Kaepernick’s “football readiness.” The sports network also notes that Kaepernick’s representatives initially “began to question the legitimacy” of the invitation.

San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick looks to throw during the NFL Football game between the San Francisco 49ers and the New York Giants in 2015.

Icon Sports Wire/Corbis/Icon Sportswire via Getty

hide caption

toggle caption

Icon Sports Wire/Corbis/Icon Sportswire via Getty

“Because of the shroud of mystery around the workout and because none of the 32 NFL teams had been informed prior to Tuesday, Kaepernick’s representatives began to question the legitimacy of the workout and process and whether it was just a PR stunt by the league,” ESPN writes.

ESPN’s Adam Schefter who broke the story, tweeted that Kaepernick’s representatives asked about changing the timing of the workout but that the league would not budge.

As Colin Kaepernick tweeted, the NFL didn’t inform his reps of Saturday’s workout in Atlanta until this morning. Kaepernick’s reps asked for workout to be on a Tuesday, the day of most workouts, but NFL said it had to be this Saturday. He asked for a later Saturday; NFL said no.

— Adam Schefter (@AdamSchefter) November 13, 2019

“Kaepernick’s reps asked for workout to be on a Tuesday, the day of most workouts, but NFL said it had to be this Saturday. He asked for a later Saturday; NFL said no,” Schefter said.

Tyler Tynes, a staff writer at the sports and culture website The Ringer, points out that Saturdays are complicated for league staff because that’s when NFL scouts fan out across the country to evaluate top college prospects and because it’s too close to Sunday NFL games.

“Kap’s representatives were told that the NFL needed an answer ‘in two hours’ if Kaepernick planned to go through with the workout,” Tynes tweeted. “A lot of people had to rearrange their schedules. They thought it conflicted with college football scouting schedules and NFL Sunday game day prep.”

NPR reached out to the NFL Players Association for comment on the timing of Kaepernick’s workout, and was directed to a five-word tweet by Executive Director DeMaurice Smith.

“Long overdue; well deserved chance.”

Long overdue; well deserved chance. https://t.co/d4FuI7qSna

— DeMaurice Smith (@DeSmithNFLPA) November 12, 2019

On social media, some people wondered whether the whole exercise is a public relations stunt.

Malik Spann of Blitz Magazine tweeted: “NFL is literally treating Kaepernick like an ex-offender trying to make him do the most obscure things for re-entry…it’s so disingenuous & fraudulent, it’s an humiliating PR process or stunt that no capable play has ever had to deal with to get back on the field.”

And Jamele Hill, a staff writer at The Atlantic, said the move by the NFL feels “disingenuous.”

“I know Colin wants to play, but this feels so disingenuous on the NFL’s part,” she tweeted. “I’ve said this since the first time Donald Trump called him out at a rally: Colin Kaepernick will never play in the NFL again. I hope I’m very wrong about this, but NFL owners are cowardly.”

I know Colin wants to play, but this feels so disingenuous on the NFL’s part. I’ve said this since the first time Donald Trump called him out at a rally: Colin Kaepernick will never play in the NFL again. I hope I’m very wrong about this, but NFL owners are cowardly. https://t.co/PBB8j4Spd7

— Jemele Hill (@jemelehill) November 13, 2019

Why is it not OK for an NFL team to simply say “we aren’t interested in Colin Kaepernick because we feel like he will be a distraction to what we are trying to accomplish”

Why is that not OK?— Colin Dunlap (@colin_dunlap) November 13, 2019

Others lamented that it “will be a distraction” for any team that signs him.

“Why is it not OK for an NFL team to simply say “we aren’t interested in Colin Kaepernick because we feel like he will be a distraction to what we are trying to accomplish” Why is that not OK?” tweeted Colin Dunlap, host of The Fan radio show in Pittsburgh.

According to NFL Network’s Ian Rapoport, the workout is scheduled for 3 p.m. ET Saturday and will play out similar to the NFL combine, where college players perform physical and mental tests for teams ahead of the NFL draft.

Details on Colin Kaepernick’s Saturday workout at the #Falcons facility that has the feel of a Combine:

— It begins at 3 pm

— Interview is at 3:15 pm

— Measurements, stretching & warmups are next.

— Timing & testing at 3:50 pm

— QB drills at 4:15

All parts recorded for 32 teams.— Ian Rapoport (@RapSheet) November 13, 2019

USA Today columnist Jarrett Bell writes that any team that wanted to do its due diligence on Kaepernick “could have brought him in way before now” but adds that “hopefully” the weekend workout is a signal teams are moving beyond “kneeling as a reason for shutting Kaepernick out of the league.”

Bell adds:

“This is an unprecedented move for the NFL to set up a showcase for one player.

“Kaepernick, though, is not just one player. He’s the one who still has some major credibility in the African-American community for sacrificing his career for a noble cause – detesting police killings of unarmed African-Americans and other social injustices.”

As part of its 30th anniversary celebrations of the wildly successful “Just Do It” slogan, Nike made the exiled athlete a centerpiece of its 30th anniversary ad push. One ad showed a black and white image of his face with the words: “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.”

Nike has been working to develop an apparel line for the athlete-turned-social activist and has donated to his “Know Your Rights” campaign, which was created to advance the well-being of black and brown communities.

Color Me Crimson: Can Football Unite Alabama?

Nothing brings people together like a common enemy, right? Also, matching jerseys and a rallying cry. University of Alabama football fans have been united by the Crimson Tide for generations, but is chanting “roll tide” really powerful enough to bridge Alabama’s political and social divides?

As Ben Flanagan writes for AL.com:

Covering Alabama football fans for the better part of a decade now, spending countless hours around hundreds of tailgates operated by all sorts of people, I’ve seen an almost universally positive and cohesive environment. Time seems to stop in Tuscaloosa when the Crimson Tide hit the field.

But is this cohesion as fleeting as the game clock?

Produced by Haili Blassingame.

Novelist Doctor Skewers Corporate Medicine In ‘Man’s 4th Best Hospital’

“The profession we love has been taken over,” psychiatrist and novelist Samuel Shem tells NPR, “with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.”

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

“Don’t read The House of God,” one of my professors told me in my first year of medical school.

He was talking about Samuel Shem’s 1978 novel about medical residency, an infamous book whose legacy still looms large in academic medicine. Shem — the pen name of psychiatrist Stephen Bergman — wrote it about his training at Harvard’s Beth Israel Hospital (which ultimately became Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) in Boston.

My professor told me not to read it, I imagine, because it’s a deeply cynical book and perhaps he hoped to preserve my idealism. Even though it has been more than 40 years since its publication, doctors today still debate whether it deserves its place in the canon of medical literature.

The novel follows Dr. Roy Basch, a fictional version of Shem, and his fellow residents during the first year of their medical training. They learn to deflect responsibility for challenging patients, put lies in their patients’ medical records and conduct romantic affairs with the nursing staff.

Basch’s friends even coin a term that is still in wide use in real hospitals today: Elderly patients with a long list of chronic conditions are still sometimes called “gomers,” which stands for “Get Out of My Emergency Room.”

Like any banned book, The House of God piqued my curiosity, and I finally read it this past year. I’m a family physician and a little over a year out of training, and I read it at the perfect time.

I got all the inside jokes about residency — and many were laugh-out-loud funny — but I am now far enough removed that the cynicism felt like satire rather than reality.

The House of God also felt dated. Basch and his cohort — who were, notably, all men, although not all white — didn’t have electronic medical records or hospital mergers to contend with. They wrote their notes about patients in paper charts. And it was almost quaint how much time the doctors spent chatting with patients in their hospital rooms.

It couldn’t be more different from my experience as a resident in the 21st century, which was deeply influenced by technology. There’s research to suggest that my cohort of medical residents spent about a third of our working hours looking at a computer — 112 of about 320 working hours a month.

In The House of God, set several decades before I set foot in a hospital, where were the smartphones? Where was the talk of RVUs — relative value units, a tool used by Medicare to pay for different medical services — or the push to squeeze more patients into each day?

That’s where Shem’s new book comes in. Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the fictional sequel to The House of God, and Basch and the gang are back together to fight against corporate medicine. This time the novel is set in a present-day academic medical center, and almost every doctor-patient interaction has been corrupted by greed and distracting technology.

Basch’s team has added a few more female physicians to its ranks, and together they battle a behemoth of an electronic medical record system. The hospital administrators in Shem’s latest book pressure the doctors to spend less time with every patient.

If The House of God is the great medical novel of the generation of physicians who came before me, perhaps Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the book for my cohort. It still has Shem’s zany brand of humor, but it also takes a hard look at forces that threaten the integrity of modern health care.

I spoke with Shem about Man’s 4th Best Hospital (which hit bookstores this week) and about his hopes for the future of medicine.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The protagonist in Man’s 4th Best Hospital, Dr. Roy Basch, doesn’t have a smartphone. I hear you don’t either. Why not?

If I had a smartphone, I would not be able to write any other novels. I have a bit of an addictive personality. I’d just be in it all the time. … I’ve got a flip phone. You can text me, but it has to be in the form of a question. I have this alphabetical keyboard. You either get an “OK” or an “N-O.”

A big theme in the novel is that technology has the potential to undermine the doctor-patient relationship. What made you want to focus on this?

I got a call out of the blue five years ago from NYU medical school. They said, “Do you want to be a professor at NYU med?” And I said, “What? Why?” And they said, “We want you to teach.” When I first got there, because I had been out of medicine [and hadn’t practiced since 1994], I figured, “Oh, I’ll look into what’s going on.” And I spent a night at Bellevue.

On the one hand, it’s absolutely amazing what medicine can do now. I remember I had a patient in The House of God [in the 1970s] with multiple myeloma. And that was a death sentence. We came in; we did the biopsy. He was dead. He was going to be dead. And that was that. Now it’s curable.

At Bellevue, I saw the magnificence of modern medicine. But like someone from Mars coming in and looking at this fresh, I immediately grasped the issues of money and effects of screens — computers’ and smartphones’.

And it just blew me away. It blew me away: the grandeur of medicine now and the horrific things that are happening to people who are really, sincerely, with love, trying to practice it. They are crunched, by being at the mercy of the financially focused system and technology.

In Man’s 4th Best Hospital, there’s a fair amount of nostalgia for the “good old days” of medicine in the 1960s and 1970s, before electronic medical records. What was better in that era?

If you ask doctors of my generation, “Why did you go into medicine?” they say, “I love the work. I really want to do good for people. I’m respected in the community, and I’ll make enough money.” Now: … “I want to have a good lifestyle.” Because you can’t make a ton of money in medicine anymore. You don’t have the respect of your community anymore. They may not even know much about you in a community because of all these [hospital] consolidations.

Do you think anything in medicine has gotten better?

The danger of isolation and the danger of being in a hierarchical system — students now are protected a lot more from that. When I was in training, interns were just so incredibly exhausted that they started doing really stupid things to themselves and patients. The atmosphere of training, by and large in most specialties, is much better.

You wrote an essay in 2002 titled “Fiction as Resistance,” about the power of novels to help make political and cultural change. What kind of resistance today can help fix American health care?

When somebody falls down, up onstage at a theater, do you ever hear the call go out, “Is there an insurance executive in the house?” No. If there are no doctors practicing medicine, there’s no health care. Doctors have to do something they have almost never done: They have to stick together. We have to stick together for what we want, in terms of the kind of health care we want to deliver, and to free ourselves from this computer mess that is driving everybody crazy, literally crazy.

Doctors don’t have a great track record of political activism, and only about half of physicians voted in recent general elections. What do you think might inspire more doctors to speak out?

Look at the difference between nurses and doctors. Nurses have great unions, powerful unions. They almost always win.

Doctors have never, ever formed anything like what the nurses have in terms of groups or unions. And that’s a big problem. So doctors somehow have to find a way — and under pressure, we might — to stick together. Doctors have to make an alliance with nurses, and other health care workers, and patients. That’s a solid group of people representing themselves in terms of what we think is good health care.

The profession we love has been taken over, with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.

Health care is a big issue for the upcoming election. What kind of changes are you hoping we’ll see?

There will be some kind of national health care system within five years. … You know, America thinks it has to invent things all over again all the time. Look at Australia. Look at France. Look at Canada. They have national systems, and they also have private insurance. Don’t get rid of insurance.

The two biggest subjects for the election are health care and health care. … The bad news is, it’s really hard to get done. The good news is, I think it’s inevitable. The good news is, it’s so bad it can’t go on.

One of the major criticisms of The House of God is that it’s sexist. It seems like your hero, Dr. Basch, has gotten a little more enlightened by the time of Man’s 4th Best Hospital. Does this reflect a change you’ve also experienced personally?

I was roundly criticized for the way women were seen in The House of God.

I remember the first rotation I had as a medical student at Harvard med was at Beth Israel, doing surgery. It got to be late at night, and I was trailing the surgeon around, and he went into the on-call room. There was a bunk bed there, and he started getting ready to go to bed. And I said, “Well, I’ll take the top bunk.” And he said, “You can’t sleep here.” So I left, and in walked a nurse. I was shocked.

Things have changed, and I am very, very glad. I don’t know if it seems conscious — I was very pleased to have total gender equity in the Fat Man Clinic [where the characters in Man’s 4th Best Hospital work] by the end of the book.

What made you feel like it was time to update The House of God?

I write to point out injustice as I see it, to resist injustice, and the danger of isolation, and the healing power of good connection. … We can help our patients to get better — but nobody has time to make the human connection to go along with getting them better.

Mara Gordon is a family physician in Camden, N.J., and a contributor to NPR. You can follow her on Twitter: @MaraGordonMD.

Let’s Play Ball! Share Your Sports-Inspired Poems

LA Johnson/NPR

NPR wants to read how sports has touched your life — in poetry form.

Maybe a home run is like getting your dream job – or asking your sweetheart for a first date felt like a Hail Mary pass. Maybe you find inspiration in E. Ethelbert Miller’s poem, If God Invented Baseball — or NPR’s poet-in-residence Kwame Alexander’s basketball poem, The Show.

You can use sport as a metaphor for our lives — or simply write about the game or team you love. And don’t feel constrained by poetry type. It can be a haiku, a sonnet, a rhyming couplet — even free verse.

Share your sports-inspired poem by following this link and it could be featured in an upcoming Morning Edition segment with Alexander.