When Countries Get Wealthier, Kids Can Lose Out On Vaccines

Mothers and their babies in Nigeria wait at a health center that provides vaccinations against polio. Vaccination rates lag in the middle-income country.

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

You’d think that as a poor country grows wealthier, more of its children would get vaccinated for preventable diseases such as polio, measles and pneumonia.

But a review published in Nature this month offers a different perspective.

“The countries that are really poor get a lot of support for the vaccinations. The countries that are really rich can afford to pay for the vaccines anyway,” says Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of the review.

But, she says, “the middle-income countries are in a tricky situation because they don’t qualify for support, yet they don’t necessarily have the financial resources and stability to purchase the vaccines.”

Adrien de Chaisemartin, director of strategy and performance at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, agrees: “More and more vulnerable populations live in middle-income countries.” Gavi, an international nonprofit that helps buy and distribute vaccines, projects that 70% of the world’s under-immunized children will live in middle-income countries by 2030.

Brazil, India, Indonesia and Nigeria were among the 10 countries with the most children who lacked basic vaccinations in 2018 — for example, shots to prevent diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis by age 1. Each of those countries meets the World Bank’s definition of a middle-income country: an average annual income (known as the gross national income, or GNI, per capita) between $1,026 and $12,375. In Nigeria alone, 3 million kids are undervaccinated. That’s 15% of the world’s total of children who lack key vaccinations.

By contrast, vaccination rates can be high in poor countries, according to global health researchers, who say that Gavi has boosted the numbers. Rwanda, for instance, despite having a GNI of $780 per person, now has a near-universal coverage rate for childhood vaccines, on par with some of the wealthiest countries.

But in general, once a country reaches a GNI per capita threshold over $1,580 for three years, support from Gavi tapers off. And despite their improved fortunes, countries don’t always choose to fund childhood vaccines.

Angola is among the middle-income countries with the lowest vaccination rates. Diamonds and oil have helped propel the country out of low-income status, and its president is a billionaire. Yet an estimated 30% to 40% of children there did not receive basic vaccines in 2018.

The lag in vaccination rates is caused by any number of reasons. “There’s a whole list of middle-income countries, and they’re not all the same,” says Kampmann.

For example, Sam Agbo, former chief of child survival and development for UNICEF Angola, says Angola’s leadership does not fully fund immunization programs. Agbo blames a political system that he says is mired in corruption, financial mismanagement and lots of debt. So it’s hard to increase the health care budget. “Primary health care is not sexy,” he says. “People are interested in building hospitals and specialized centers rather than investing in preventive care.”

Gavi’s de Chaisemartin groups Angola with other resource-rich but corruption-plagued countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea and East Timor. “These are countries where the GNI is relatively high because of their oil resources, for the most part, but that doesn’t translate into a stronger health system,” says de Chaisemartin.

Then there’s the matter of cost. Countries that buy vaccines on the open market might pay over $100 a shot.

Public attitudes also play a role. In Brazil, which is on the high end of the middle-income spectrum, an immunization program that once outperformed World Health Organization recommendations has been declining for three years. Jorge Kalil Filho, an immunology professor at the University of Sao Paulo, says public inattention and anti-vaccine campaigns, popular on social media, are undermining progress.

De Chaisemartin says the global health community needs to adjust to an unprecedented global economic shift. “Fifteen years ago, the world was divided between poor countries, where most poor people were living, and high-income countries,” says de Chaisemartin. “Now you have a lot of middle-income countries with very poor and vulnerable populations.”

Opioid Addiction In Jails: An Anthropologist’s Perspective

A new book by anthropologist and physician Kimberly Sue tells the stories of women navigating opioid addiction during and after incarceration.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Dr. Kimberly Sue is the medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, a national advocacy group that works to change U.S. policies and attitudes about the treatment of drug users. She’s also a Harvard-trained anthropologist and a physician at the Rikers Island jail system in New York.

Sue thinks it’s a huge mistake to put people with drug use disorder behind bars.

“Incarceration is not an effective social policy,” she says. “It’s not an evidence-based policy. It’s not effective in deterring crime. But we continue to rely on it for reasons that have to do with morality.”

While a quarter or more of the U.S. prison population has an addiction to opioids, only 5% of those individuals receive medication for their chronic condition, Sue notes, despite the growing agreement among doctors that this approach to treatment saves lives.

In addition to her Rikers Island work with incarcerated women, Dr. Kimberly Sue is medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, an advocacy group that works to change U.S. policies and attitudes toward syringe exchanges and other evidence-based approaches to treating drug addiction.

Van Asher

hide caption

toggle caption

Van Asher

Statistics suggest that women might benefit most from improvements in treatment, she says. The rate of death from prescription opioid overdose has gone up nearly 500% among women since 1999, compared with 200% among men. And in recent decades, women’s rate of incarceration has grown at twice the rate of men’s.

We spoke with Sue about her new book, Getting Wrecked: Women, Incarceration, and the American Opioid Crisis, which is based on firsthand accounts from female inmates she has treated.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What are some of the arguments that jail is not the best public health solution to opioid use?

Incarceration in many cases harms people. We know that, for example, having been in solitary confinement increases your risk of death after release — like in the case of Kalief Browder, a young Bronx man who killed himself after three years at Rikers.

And the rate of opioid overdose in the first two weeks after people leave prison and jail is between 30 and 120 times higher than the general population.

In most of the county-level jails in this country, people are forced to withdraw off lifesaving, stabilizing medications [like methadone] against their will. Methadone is a treatment for opioid use disorder that you cannot access in jails in many places in this country.

There are documented cases of suicide around the country — including in my book — of people who are going through withdrawal in jails and either committing suicide or dying as a combination of medical neglect and loss of body fluids related to dehydration.

Can you describe that example from your book?

One of the women I took care of and interviewed at MCI-Framingham, a women’s state prison in Massachusetts, was in the health services unit — where they send people when they’re first coming in — and she heard someone withdrawing from methadone. That person was screaming — she was, you know, in agony. And then [my patient] stopped hearing her screaming. [My patient and other prisoners] tried to get the guards’ attention. And they found out that she had hung herself.

People going through withdrawal in jail health facilities — it’s not the same as being an inpatient in my hospital, with nurses monitoring you and someone with medical training taking care of you. These are cinder block cells where people are going through diarrhea, vomiting, sweats, muscle aches. And many jails around the country are getting lawsuits that are being settled for situations like this.

People in the commercial jail and prison system believe that what they do is the best way, but it’s not the equivalent of the standard of care that we offer in the community.

How do jails and prisons explain not having methadone available, if that endangers lives?

And liquid methadone costs pennies. It’s not a matter of cost — it’s a matter of political will.

The way I like to describe it is, if your brother had a heart attack and then became incarcerated, we would continue all six of the lifesaving medications he was prescribed, no matter what the cost — even hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. But if he had an opioid overdose and became incarcerated, they’d just stop the medication he was prescribed for opioid use disorder — they just wouldn’t give it to him.

In no other chronic health condition do we discriminate like this. There’s such a stigma that’s encoded into our policies.

You write about that in your book: “The crisis we face is not opioids. The crisis we face is a war on people who use drugs, and on our reliance on incarceration as a catch-all policy solution.”

Yes. And it’s not just opioids. As a doctor who takes care of people who use drugs, I don’t have a problem with people who use drugs. But there are so many people in this country who really hate them and don’t care if they die. Or don’t care if they are able to have lives of dignity and respect.

Is that because of stigma getting in the way? The idea that if you do drugs, you deserve whatever happens to you?

Yeah. The idea that substance use is a disease of the will is very heavily entrenched in American ideology. We have a hatred of people who are dependent on anything — including the government — for support. The idea of people being on welfare, the idea of people not working. We have these very strong puritanical roots and the idea that we make our bed, we lie in it, and you pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. It pits people against each other in a way.

People who use drugs — they have a physical dependence on a substance. It doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re bad people, but our society tells them that they’re bad people.

Notice that I don’t call substance use disorder a disease. It’s really much more complex than that. I don’t want it to be all medicalized, because so much of the answer is not in medicine. If you think about getting addicted to heroin or pills in West Virginia, a lot of it might have to do with poverty. As a doctor, so much of what I’d like to be able to do for you is to give you a job, you know? To give you an education and more opportunities. I’d like to give you a prescription for housing.

How does all this more specifically impact women?

For as long as we’ve been a country, women have been criminalized — not only for substance use, but for disorderly housekeeping, for leaving marriages, for abortion, for lewd behavior. Women have been criminalized basically for being seen as deviating from a certain upper-middle-class white morality.

Because women have the potential to be pregnant or are often mothers, there’s this added moralizing directed at women who use drugs. There have been laws, for example, that send women to jail for twice as long as they would sentence men for drinking in public, because of the idea that women had farther to fall.

Some of the women in my book were low-level drug dealers. And they didn’t have anything to give prosecutors, so they would get thrown under the bus by the men who were much higher up who had more information. So they would take the rap.

The rate of incarceration of women is still relatively small compared to that of men, but it’s gone up 840% over the past 40 years.

Other countries don’t do this. Portugal is held up as one of those models.

What is different in Portugal?

Portugal has decriminalized drug use. So if someone has problematic substance use, they don’t go to prison or jail for that.

So, is there no stigma associated with drug use there?

I just listened to a podcast episode by this guy who went around Portugal and asked people, “How does your society feel about people who use drugs?” And the people he interviewed were like, “They’re just people struggling. It’s not their problem — it’s a social problem.”

Basically, substance use is treated like a social condition, and all of the services that an individual would need get wrapped around it. They have mobile vans to bring methadone to where you’re living. Their system shows that it doesn’t have to be the way we do it in the U.S.

After Portugal decriminalized drug use, overdose deaths decreased by 80% and HIV rates went from 52% to 6%. It’s not a perfect model, but it’s so much better.

Despite Challenges To ACA, Florida Enrollment Rises

The annual enrollment period for health plans under the Affordable Care Act is underway and Florida is expected to lead the nation in signups. Despite legal challenges to the law, it remains popular.

The Controversy Around Virginity Testing

NPR’s Michel Martin talks with Sophia Jones, senior editor for The Fuller Project, about the controversy surrounding virginity testing.

You Can Get A Master’s In Medical Cannabis In Maryland

Maryland now offers the country’s first master’s degree in the study of the science and therapeutics of cannabis. Pictured, an employee places a bud into a bottle for a customer at a weed dispensary in Denver, Colo.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Summer Kriegshauser is one of 150 students in the inaugural class of the University of Maryland, Baltimore’s Master of Science in Medical Cannabis Science and Therapeutics, the first graduate program of its type in the country.

This will be Kriegshauser’s second master’s degree and she hopes it will offer her a chance to change careers.

“I didn’t want to quit my really great job and work at a dispensary making $12 to $14 an hour,” says Kriegshauser, who is 40. “I really wanted a scientific basis for learning the properties of cannabis — all the cannabinoids and how they interact with the body. I wanted to learn about dosing. I wanted to learn about all the ailments and how cannabis is used within a medical treatment plan, and I just wasn’t finding that anywhere,” she adds.

The program stands largely alone: Some universities offer one-off classes on marijuana and two have created undergraduate degrees in medicinal plant chemistry, but none have yet gone as far as Maryland.

Stretched over two years and conducted almost exclusively online, the program launched as an increasing number of jurisdictions across the country legalize pot — primarily for medical uses, but in some places recreational, as well.

As of mid-October, nearly three dozen states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands had legalized medical cannabis, creating an ever-expanding universe of opportunities for people looking to grow, process, recommend and sell the drug to patients. And given how quickly attitudes and laws on cannabis are shifting, those opportunities are expected to keep expanding.

But even as the industry has quickly grown, expertise has remained largely informal. And for people looking to change careers, like Kriegshauser, getting into the legal cannabis field can seem risky, with the likely job options hard to come by.

The University of Maryland credits the overwhelming response to its graduate program to that desire for more information and opportunity. More than 500 hopefuls applied for what was supposed to be a class of 50, prompting the university to increase the size of the inaugural class threefold. And the class is geographically diverse, coming from 32 states and D.C., plus Hong Kong and Australia.

The students take four required core courses — including one on the history of medical weed and culture, and two basic science classes. Students then choose between a number of electives.

Leah Sera, a pharmacist and the program’s director, says officials at the university see a parallel trend. More and more of their graduates were entering a professional world where cannabis is seen as an alternative medicine for any number of ailments, and one that more patients are curious about.

“There have been a number of studies, primarily with health professionals, indicating that there is an educational gap related to medical cannabis — that health professionals want more education because patients are coming to them with questions about cannabis and therapeutic uses,” Sera says.

Pharmacist Staci Gruber teaches at Harvard Medical School and is leading one of the country’s most ambitious research projects on medical marijuana at McLean Hospital in Boston.

She says Maryland’s program is proof that as the drug becomes ever more present among patients, more research on its effects will be needed.

“I know some say, ‘Oh, it’s just a moneymaker for the institution,’ but it’s because people are asking for it,” she says. “People are interested in learning more and knowing more, so [Maryland’s program] underscores the need to have more data.”

That’s the challenge for an academic program on cannabis; the drug remains largely illegal under federal law, which has hampered its study over the years and means very little concrete research exists for students to dig into. But as that changes, Sera says, the program will continue to evolve.

And she expects that students will see immediate opportunities in the rapidly expanding industry once they graduate.

There remains plenty of uncertainty, of course, and as the recreational use of weed is made legal in more places, established medical cannabis programs, and their associated jobs, may dwindle. But Summer Kriegshauser says making the leap into Maryland’s program made sense for her — and she bets it will pay off.

Saturday Sports: LA Clippers, 49ers, Bruins

The LA Clippers get fined, the San Francisco 49ers are the winningest team in the NFL, and the Boston Bruins are out for revenge. Scott Simon talks to Howard Bryant.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Know what gets me through the week? Time for sports.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

SIMON: The NBA debate, should coaches bench their superstars just so they can take a rest? And holy, Garoppolo, the 49ers are undefeated. And the Bruins are cruising. We’re joined by Howard Bryant of ESPN. Howard, thanks so much for being with us.

HOWARD BRYANT: Scott, the derisive way in which you said rest. Do you really mean that?

SIMON: Well, all right.

BRYANT: (Laughter).

SIMON: Let me pose the question for you, you know, in perhaps a better stated way. The NBA fined the LA Clippers $50,000. Coach Doc Rivers said Kawhi Leonard – he didn’t start him. The league said he was injured. Coach Doc said, you know, actually he was fine. He was OK. He was great, in fact. Now…

BRYANT: (Laughter).

SIMON: …Should superstars be benched particularly early in the season because the coach, maybe only meaning to be conscientious, wants to save them for important games further on into the season and the playoffs?

BRYANT: Yeah, I understand the perspective. The NBA season is a grind. It’s a very, very long season. You’re starting out in October. You get to the playoffs in late April. And then the playoffs last two months. So the regular – the postseason doesn’t even end until almost July. So I understand the impulse. I also understand when you’re a coach, your attitude is, look; you’re paying me to win important games. You’re paying me to win championships, especially when you’re the Los Angeles Clippers, where you get Kawhi Leonard from Toronto, you – who just won a championship a few months ago. And the end goal for the Clippers is to be hosting the trophy a few months from now.

I also understand it from a consumer standpoint, which is where if you’re going to pay 150 bucks a ticket to go see the best players play, then for that one game that you’re going to, you want to see Kawhi Leonard against Giannis Antetokounmpo, which is – which was the matchup. You had the Milwaukee Bucks team that is supposed to go to the NBA Finals against the Clippers team that is supposed to go to the NBA Finals. And so if you’re the paying customer, you show up at that the arena, and that matchups not going to happen, that’s a bitter pill. That’s the reason why you paid all that money.

SIMON: Yeah. I mean, the NBA sells itself as entertainment. And, you know, great entertainers show up when the curtain goes up.

BRYANT: Well, exactly. And the bottom line on that is if you’re Doc Rivers, if you’re the coach, you’re thinking to yourself, OK, what are you going to remember more? Are you going to remember me not playing Kawhi Leonard in November, or are you going to remember Kawhi Leonard not being healthy and ready to go when the big games start when the playoffs begin?

SIMON: NFL season is halfway over. The San Francisco 49ers, who were 4-12 last year, are now 8-0. They’ve got a big Monday night game against the Seahawks. Are they as good as 8-0?

BRYANT: Well, they’re good. They’re really good. And we’re going to find out how good they are because the Seahawks are 7-2. And that’s a rivalry game. And we know how big that is. You haven’t had that kind of excitement in San Francisco for a really long time, haven’t won a Super Bowl since 1995, haven’t been to the Super Bowl since Colin Kaepernick took them there back in 2011 against the Ravens. And so when you are looking at this team, you get – you’re excited. You’re excited. And I think that Garoppolo’s a great, great quarterback. They’re doing it with defense. Their defense is almost as good as the Patriots. So – it may be better. And you’ve got George Kittle. You’ve got a nice tight end there. And so they run the ball. They catch it. They do everything you’re supposed to do to win. And they turn the ball over, as well. So they get turnovers. So they’re doing all the things that championship teams have to do. But it’s halfway there. It’s going to be a big game Monday night.

SIMON: NHL, the Bruins, of course, lost Game 7 in the Stanley Cup, but they’re back with a vengeance. Can they keep it up?

BRYANT: Well, once again, long season. You go out and you lose the Stanley Cup at home, and you want to go on a revenge tour, but you’ve got to play a long way. The Bruins have lost two in a row now. And it’s – a lot of good teams out there. St. Louis is still a good team. I think that what they have to do is you’ve got to maintain that emotion, but at the same time realize it’s a marathon. But they’re really good to watch.

SIMON: Howard Bryant of ESPN, thanks so much for being with us my friend. Talk to you soon.

(SOUNDBITE OF LARI BASILIO’S “A MILLION WORDS”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Nike To Investigate Mary Cain’s Claims Of Abuse At Its Nike Oregon Project

Mary Cain says she endured constant pressure to lose weight and was publicly shamed during her time at the Nike Oregon Project. She’s seen here in the 1500-meter race at the 2014 USA Track and Field Championships. Cain won silver in that race; she had turned 18 just a month earlier.

Christopher Morris /Corbis via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Morris /Corbis via Getty Images

Nike says it’s investigating claims of physical and mental abuse in its now-defunct Oregon Project in response to former running phenom Mary Cain’s harrowing account of her time under disgraced coach Alberto Salazar.

Cain says she paid a steep price during her time with the elite distance-running program, from self-harm and suicidal thoughts to broken bones related to her declining health.

She is speaking out less than a month after Nike shut down the Oregon Project in the wake of a four-year doping ban against Salazar, which he has said he plans to appeal. A string of elite athletes — Cain’s former Oregon Project teammates — say they back her claims.

“I joined Nike because I wanted to be the best female athlete ever,” Cain says in an opinion video produced by The New York Times. “Instead, I was emotionally and physically abused by a system designed by Alberto and endorsed by Nike.”

Cain, 23, shot to fame in 2012 as a blazingly fast New York teenager who shattered national records. She began training with Salazar full time after finishing high school, skipping the NCAA track circuit altogether. At the time, she was seen as a prodigy, a sure bet to win Olympic gold and set world records. In 2013, she won the International Athletic Foundation’s Rising Star Award.

But Cain says Salazar and other staff members constantly pressured her to lose weight — and that her health suffered dramatically as a result.

“When I first arrived, an all-male Nike staff became convinced that in order for me to get better, I had to become thinner and thinner and thinner,” Cain says in the Times video.

Cain says that mantra — and public shaming about her weight — led to a spiral of health problems known as relative energy deficiency in sport, or RED-S Syndrome. Also called the Female Athlete Triad, the condition is triggered when athletes take in too few calories to support their training. Next, they stop having menstrual periods — and lose vital bone density as a result.

“I broke five different bones” because of RED-S, Cain says.

Cain says that after a disappointing finish in a race in 2015, Salazar yelled at her in front of a large crowd, saying he could tell she had gained 5 pounds.

“It was also that night that I told Alberto and our sports psych that I was cutting myself and they pretty much told me that they just wanted to go to bed,” Cain said. Soon afterward, she says she decided to leave Salazar’s program and return home to Bronxville, N.Y.

Salazar denies Cain’s accusations against him. NPR’s attempts to contact Salazar for comment so far have been unsuccessful. But The Oregonian quotes a statement from the famous coach in which he says, “To be clear, I never encouraged her, or worse yet, shamed her, to maintain an unhealthy weight.”

In that message, Salazar also says that Cain “struggled to find and maintain her ideal performance and training weight.” But he says he discussed the issue with Cain’s father, who is a doctor, and referred her to a female doctor, as well.

In response to Cain’s allegations, Nike says, “We take the allegations extremely seriously and will launch an immediate investigation to hear from former Oregon Project athletes.”

The company calls Cain’s claims “deeply troubling,” but it says that neither Mary nor her parents had previously raised the allegations.

“Mary was seeking to rejoin the Oregon Project and Alberto’s team as recently as April of this year and had not raised these concerns as part of that process,” a Nike spokesperson said in an email to NPR.

On Friday morning, Cain addressed her recent attempt to rejoin the team, saying via Twitter, “As recently as this summer, I still thought: ‘maybe if I rejoin the team, it’ll go back to how it was.’ But we all come to face our demons in some way. For me, that was seeing my old team this last spring.”

No more wanting them to like me. No more needing their approval. I could finally look at the facts, read others stories, and face: THIS SYSTEM WAS NOT OK. I stand before you today because I am strong enough, wise enough, and brave enough. Please stand with me.

— Mary Cain (@runmarycain) November 8, 2019

Over the summer, Cain says, she became convinced that Salazar only cared about her as “the product, the performer, the athlete,” not as a person. She adds that she decided to go public with her story after the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency punished Salazar earlier this year. Now Cain is calling for Nike to change its ways — and to ensure the culture that thrived under Salazar is eradicated.

“In track and field, Nike is all-powerful,” Cain says in the Times video. “They control the top coaches, athletes, races, even the governing body. You can’t just fire a coach and eliminate a program and pretend the problem is solved.”

She adds, “My worry is that Nike is merely going to re-brand the old program and put Alberto’s old assistant coaches in charge.”

The list of runners who have stepped forward to support Cain includes Canadian distance runner Cameron Levins, a former Olympian and NCAA champion who trained in the Oregon Project.

“I knew that our coaching staff was obsessed with your weight loss, emphasizing it as if it were the single thing standing in the way of great performances,” Levins said in a tweet directed at Cain.

“I knew because they spoke of it openly among other athletes,” he added.

Another athlete, former NCAA champion Amy Yoder Begley, said she was kicked out of the Oregon Project after she placed sixth in a 10,000-meter race in 2011.

After placing 6th in the 10,000m at the 2011 USATF championships, I was kicked out of the Oregon Project. I was told I was too fat and “had the biggest butt on the starting line.” This brings those painful memories back. https://t.co/ocIqnHDL8F

— Amy Yoder Begley OLY ???? (@yoderbegley) November 8, 2019

“I was told I was too fat and ‘had the biggest butt on the starting line,’ ” Begley said via Twitter. “This brings those painful memories back.”

Cain says her parents were “horrified” when she told them about her life in the Nike Oregon Project. “They bought me the first plane ride home,” she says. “They were like, get on that flight, get the hell out of there.”

On Friday, Cain thanked Levins for his support and said, “For so long, I thought I was the problem. To me, the silence of others meant that pushing my body past it’s healthy limits was the only way. But I know we were all scared, and fear keeps us silent.”

As for what changes Cain would like to see, she tells the Times that her sport needs more women in power.

“Part of me wonders if I had worked with more female psychologists, nutritionists and even coaches, where I’d be today,” Cain says. “I got caught in a system designed by and for men which destroys the bodies of young girls. Rather than force young girls to fend for themselves, we have to protect them.”

After being off the track-and-field radar for several years, Cain ran a four-mile race on Mother’s Day in Central Park. In an interview earlier this year, she talked about what she would write in a letter to her younger self.

Here’s part of what Cain told Citius Mag:

“I think my letter would say, ‘Go have that milkshake. Go see that movie. Go out with that friend. Love running and commit to running but the best way to do that is to love yourself and commit to yourself. Make sure you’re doing those other things as well so that once you go out for a run, you’re so happy to be there.'”

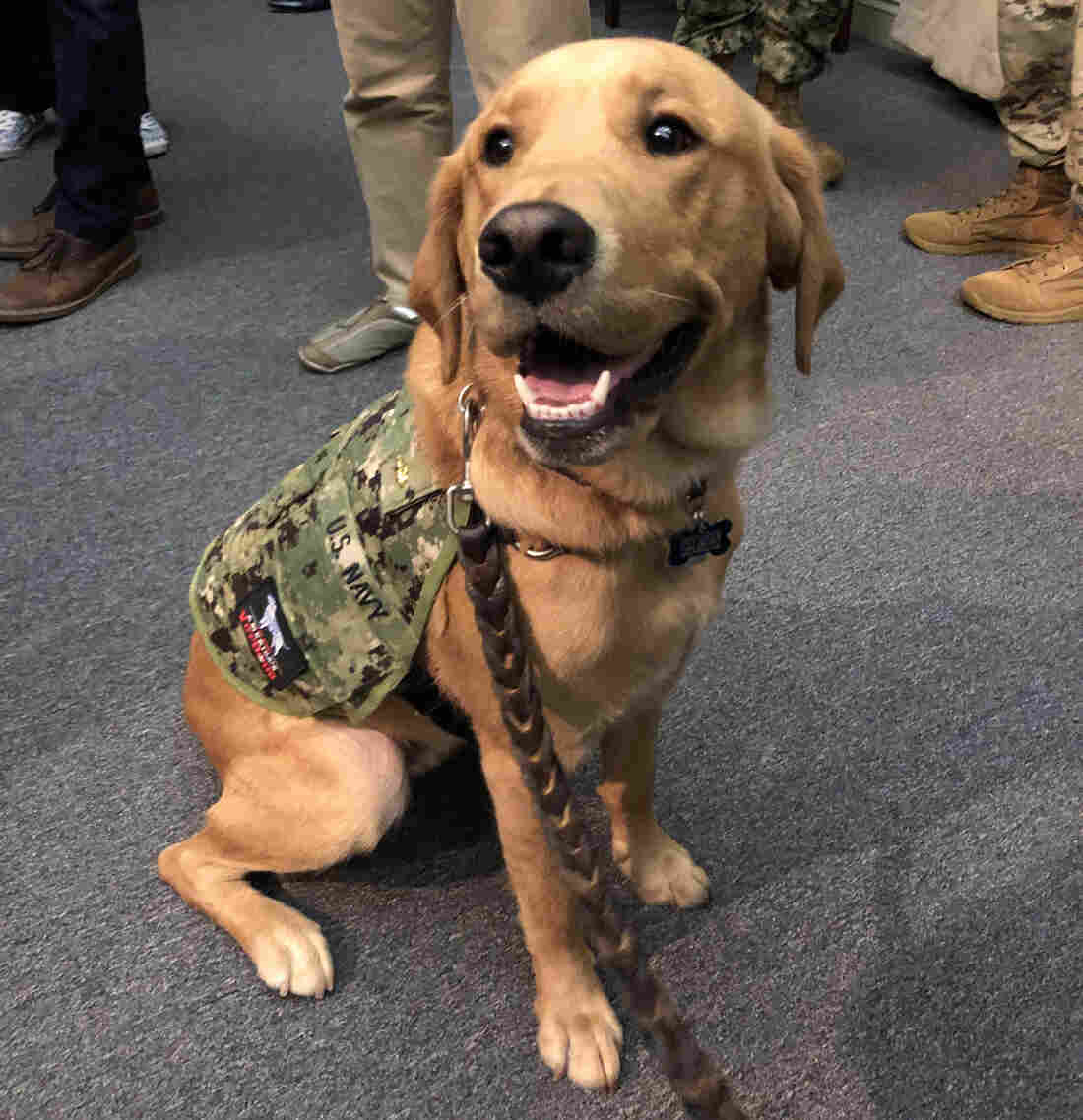

High-Ranking Dog Provides Key Training For Military’s Medical Students

Service dogs can be trained to provide very different types of support to their human companions, as medical students learn from interacting with “Shetland,” a highly skilled retriever-mix.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

The newest faculty member at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences has a great smile ? and likes to be scratched behind the ears.

Shetland, not quite 2 years old, is half-golden retriever, half-Labrador retriever. As of this fall, he is also a lieutenant commander in the Navy and a clinical instructor in the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology at USUHS in Bethesda, Md.

Among Shetland’s skills are “hugging” on command, picking up a fallen object as small as a cellphone and carrying around a small basket filled with candy for harried medical and graduate students who study at the military’s medical school campus.

But Shetland’s job is to provide much more than smiles and a head to pat.

“He is here to teach, not just to lift people’s spirits and provide a little stress relief after exams,” says USUHS Dean Arthur Kellermann. He says students interacting with Shetland are learning “the value of animal-assisted therapy.”

The use of dogs trained to help their human partners with specific tasks of daily life has ballooned since studies in the 1980s and 1990s started to show how animals can benefit human health.

But helper dogs come in many varieties. Service dogs, like guide dogs for the blind, help people with disabilities live more independently. Therapy dogs can be household pets who visit people in hospitals, schools and nursing homes. And then there are highly trained working dogs, like the Belgian Malinois, that recently helped commandos find the Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Shetland is technically a “military facility dog,” trained to provide physical and mental assistance to patients as well as interact with a wide variety of other people.

His military commission does not entitle him to salutes from his human counterparts.

“The ranks are a way of honoring the services [of the dogs] as well as strengthening the bond between the staff, patients and dogs here,” says Mary Constantino, deputy public affairs officer at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. “Our facilities dogs do not wear medals, but do wear rank insignia as well as unit patches.”

USUHS, which trains doctors, dentists, nurses and other health professionals for the military, is on the same campus in suburban Washington, D.C. Two of the seven Walter Reed facility dogs ? Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Sully (the former service dog for President George H.W. Bush) and Marine Sgt. Dillon ? attended Shetland’s formal commissioning ceremony in September as guests.

The Walter Reed dogs, on campus since 2007, earn commissions in the Army, Navy, Air Force or Marines. They wear special vests designating their service and rank. The dogs visit and interact with patients in several medical units, as well as in physical and occupational therapy, and help boost morale for patients’ family members.

But Shetland’s role is very different, says retired Col. Lisa Moores, USUHS associate dean for assessment and professional development.

“Our students are going to work with therapy dogs in their careers and they need to understand what [the dogs] can do and what they can’t do,” she says.

As in civilian life, the military has made significant use of animal-assisted therapy. “When you walk through pretty much any military treatment facility, you see therapy dogs walking around in clinics, in the hospitals, even in the ICUs,” says Moores. Dogs also play a key role in helping service members who have post-traumatic stress disorder.

Students need to learn who “the right patient is for a dog, or some other therapy animal,” she says. “And by having Shetland here, we can incorporate that into the curriculum, so it’s another tool the students know they have for their patients someday.”

The students, not surprisingly, are thrilled by their newest teacher.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, says the Walter Reed dogs used to visit the school’s 1,500 students and faculty fairly regularly, but “having Shetland here all the time is optimal.” Wyatt says the only thing she knew about service dogs before — or at least thought she knew — was that “you’re not supposed to pet them.” But Shetland acts as both a service dog and a therapy dog, so can be petted, Wyatt learned.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, shares a hug with Shetland. The dog’s military commission does not entitle him to salutes.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

Having Shetland around helps the students see “there’s a difference,” Wyatt says, and understand how that difference plays out in a health care setting. Like his colleagues Sully and Dillon, Shetland was bred and trained by America’s VetDogs.

The New York nonprofit provides dogs for “stress control” for active-duty military missions overseas, as well as service dogs for disabled veterans and civilian first responders.

Many of the puppies are raised by a team made up of prison inmates (during the week) and families (on the weekends), before returning to New York for formal service dog training. National Hockey League teams such as the Washington Capitals and New York Islanders also raise puppies for the organization.

Dogs can be particularly helpful in treating service members, says Valerie Cramer, manager of America’s VetDogs service dog program. “The military is thinking about resiliency. They’re thinking about well-being, about decompression in the combat zone.”

Often people in pain won’t talk to another person but will open up in front of a dog. “It’s an opportunity to start a conversation as a behavioral health specialist,” Cramer says.

While service dogs teamed with individuals have been trained to perform both physical tasks and emotional ones — such as gently waking a veteran who is having a nightmare — facility dogs like Shetland are special, Cramer says.

“That dog has to work in all different environments with people who are under pressure. It can work for multiple handlers. It can go and visit people; can go visit hospital patients; can knock over bowling pins to entertain, or spend time in bed with a child.”

The military rank the dogs are awarded is no joke. They can be promoted ? as Dillon was from Army specialist to sergeant in 2018 ? or demoted for bad behavior.

“So far,” Kellermann says, “Shetland has a perfect conduct record.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Scandal Brings Down A Remarkable College Basketball Team In ‘The City Game’

If you ask a college basketball fan to name the best squads of all time, chances are you’ll hear some of the same names: the 1975-76 Indiana Hoosiers, the 1990-91 Duke Blue Devils, the 1966-67 UCLA Bruins.

Somewhat forgotten to younger basketball aficionados, though, are the 1949-50 City College of New York Beavers, who became the first and only team to win both the National Invitation Tournament and the NCAA Tournament.

As Matthew Goodman writes in his wonderful new book, The City Game, there’s a reason for that: The team’s championships were overshadowed by a point-shaving scandal that engulfed not just CCNY but also several other schools across the nation in the early 1950s. Goodman’s book is a fascinating look at a team full of talented young men who torpedoed their careers because they were unable to resist the lure of easy money.

The CCNY Beavers were, by all accounts, a remarkable team. They “operated something like a five-man jazz combo, with each player improvising off a few basic patterns … together creating something fast and complex and unpredictable,” Goodman writes, benefitting from the coaching of basketball legend Nat Holman and assistant coach Bobby Sand. They were also a diverse team in an era when racism and anti-Semitism ran rampant: The team was composed of 11 Jewish players and four African Americans; all of them were the children of immigrants.

While the players were unquestionably thrilled to get the chance to play for “the working-class Harvard,” there was still an air of resentment on the part of the students. Many chafed against Holman, an “arrogant and aloof” man who routinely verbally abused his players, Goodman writes. And the students weren’t happy that they were made to do their own laundry on road trips while their coaches opted for dry-cleaning and fancy steak dinners.

So it wasn’t surprising when some of the team’s players were lured into a point-shaving operation. Point-shaving involves players deliberately missing shots and blocks in order to keep the point margin below the spread; basketball, where the scores are typically high and the pace of the game is fast, is more prone to point-shaving than other sports. “An athlete whose long-honed competitive nature would recoil at the prospect of intentionally losing a game might have less resistance to creating a smaller margin of victory,” Goodman notes.

For some of the players — “not all of them poor but none of them rich” — it proved irresistible. Some longed to support their families living in overcrowded tenements; others were drawn into the scheme by peer pressure: “I wanted the guys to like me,” explained Irwin Dambrot, a small forward on the team.

Unfortunately for the Beavers, the point-shaving plot happened to occur at the same time as another gambling scandal, one that would eventually bring down New York Mayor William O’Dwyer. The city’s district attorneys became obsessed with finding and prosecuting bookmakers, and it wasn’t long before they discovered that college players were routinely shaving points. CCNY got hit particularly hard: “The entire starting five of the City College double-championship squad had now been arrested, along with the top two reserves,” Goodman writes. “The shame of the team was complete.”

Goodman’s book is at once a history of the CCNY team’s remarkable championship season (and the less remarkable one after that) as well as a close look at organized crime and police corruption in post-WWII New York. Goodman does a wonderful job recounting the Beavers’ games — fans of the game will find much to love in his play-by-play descriptions of CCNY’s march to the championships, but you don’t need to be a hardcore basketball fan to keep up.

He also proves to be excellent at providing historical context for the scandal. College basketball was huge in post-war New York; CCNY regularly played their games at Madison Square Garden, selling out the venue routinely. The background makes the fallout from the players’ arrests all the more heartbreaking: Students, Goodman writes, “would no longer flock to the Garden to watch their team play; everyone understood that this portion of their lives, and of the life of their school, had come to an end.”

Goodman follows the students in the years after the scandal: “They lived with dignity but also with a lingering sense of shame and anger and frustration. Their story, they always believed, was far larger than they were.” Some did end up finding deliverance: Floyd Layne, the Beavers’ remarkable shooting guard, never got to play in the NBA, but did eventually become the first African American to serve as CCNY’s head basketball coach. Goodman doesn’t let the players off the hook, but writes about them with a real sympathy: They were essentially kids who paid a harsh price for making admittedly poor decisions, he argues.

The CCNY point-shaving scandal remains, decades after it happened, a heartbreaking story of venality, and Goodman turns out to be the perfect author to tell it. The City Game is a gripping history of one of college basketball’s darkest moments, an all too human tale of young people blowing up their futures in a misguided attempt to make good.

‘Just The Right Policy’: Pete Buttigieg On His ‘Medicare For All Who Want It’ Plan

Credit: NPR

Don’t see the video? Click here.

The field of 2020 presidential candidates with health care overhaul plans is crowded, and Pete Buttigieg, mayor of South Bend, Ind., is drawing lines of distinction between his and his competitors’ proposals.

“I mean, the reality is, all these beautiful proposals we all put forward, their impact is kind of multiplied by zero if you can’t actually get it through Congress, and it’s one of the reasons why I do favor the approach that I have,” he said.

Democratic presidential candidate Mayor Pete Buttigieg in South Bend, Ind.

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

Buttigieg would offer public health insurance to those who want it while also keeping private health care plans available. Other candidates’ proposals, including “Medicare for All” — backed by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren — would replace the current system with a single-payer, government-run program and eliminate private insurance altogether.

Buttigieg spoke to two undecided Indiana voters and NPR host Scott Simon as part of the network’s Off Script series of interviews with 2020 presidential candidates.

“We make sure that everybody can afford [public health insurance], but we don’t require you to take it. And partly I think that’s just the right policy, because I think people should be able to choose,” he said. “But it’s also really important that that’s a policy that commands the support of most Americans. … We have a moment where we can get something that big done and most Americans want it done. That’s not true of some of the other ideas out there, which would make it much harder to actually achieve them no matter how good they sound in campaign season.”

Mayor Pete Buttigieg, center, at Pegg’s Diner in South Bend, Ind. with undecided voters Michael Logan, left, Jacque Stahl, back to camera, and NPR host Scott Simon.

Lucy Hewitt/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Hewitt/NPR

The voters — Michael Logan, a 54-year-old retired Michigan State Police detective sergeant, and Jacque Stahl, 37, who works with a health care group in South Bend — pressed Buttigieg on his plan.

Stahl’s 5-year-old son has a condition that requires treatment that if uninsured would cost her family $35,000 a month. She said the health care system can be confusing even for those in the industry, and Americans who do their best to stay in-network can be faced with large surprise medical bills.

Jacque Stahl, 37, who works with a health care group in South Bend, Ind., and Michael Logan, a 54-year-old retired Michigan State Police detective sergeant.

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Hewitt for NPR

Buttigieg told her he’s proposing to end surprise billing.

“We would set 200 percent of Medicare, would be the highest that even an out-of-network therapy could cost when you have a hospitalization or something like that,” he said. “Because some of this is also the responsibility of hospitals and health care providers. This can’t just be handled on the insurance side.”

Buttigieg is polling second in Iowa according to a Quinnipiac University poll released Wednesday. The poll shows Buttigieg polling at 19%, trailing Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who is receiving 20%. Iowa holds the first-in-the-nation caucuses on Feb. 3.

Off Script is edited and produced for broadcast by Ashley Brown and Bridget De Chagas. Eric Marrapodi is Off Script’s supervising editor.