A month after Hurricane Dorian devastated the Bahamas, Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance gets a hug from husband Ferrier Petit Homme. The storm destroyed their home on Grand Abaco Island. They are now living with China Laguerre in Nassau.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Editor’s note: This story includes images that some readers may find disturbing.

Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance was crying on the side of a road when China Laguerre spotted her.

Hurricane Dorian destroyed LaFrance’s newly constructed house in Great Abaco Island on the northern edge of the Bahamas the same night she moved in. That was on Sept. 1.

She then moved into a hotel offering free shelter in Nassau with her husband and 14-year-old son. But she says they were kicked out when staff found her son talking to guests.

She had nowhere to go. So Laguerre invited her to come stay at the home she shares with her parents and her brother.

Bodies lay in the debris left by Hurricane Dorian, which decimated Marsh Harbour on Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas on Sept. 6. The Mudd, an immigrant shantytown in Marsh Harbour, was home to about 8,000 Haitians, some of whom have lived in the area for several generations.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

“If these people didn’t help, I didn’t know what we were going to do,” says LaFrance. “I just thank God for these people.”

LaFrance is one of thousands of Haitians who lived in Abaco but were displaced to Nassau after the storm. The government’s policy is to keep evacuees off Abaco until power, water and housing is restored.

But life in Nassau is not easy for evacuees: Haitians in the Bahamas — some recent immigrants, others who have lived in the Bahamas for generations — say that they face discrimination by their Bahamanian neighbors and that government officials that has made it harder to access emergency aid, shelter and health care and to find jobs to get back on their feet after the storm. On Oct. 2, Prime Minister Hubert Minnis announced that Haitians in the Bahamas without documentation would be deported.

So some are relying on the kindness of strangers — and Laguerre’s home has emerged as the headquarters of an ad hoc Haitian community support network.

Ferrier Petit Homme (left) and Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance pray every evening with other Dorian evacuees as well as members of the Laguerre family, who welcomed them into their home. This night was particularly painful: Sherrine’s 14-year-old son ran away in the morning. He returned two days later.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

While volunteering at a local hospital after the storm, Laguerre, 31, met Haitian evacuees who inspired her to open her doors to strangers.

“I feel sorry because it could’ve been me,” she says.

From left: Justin Bain, Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance and Ferrier Petit Homme have little space to sleep in the family home of China and brother Odne Laguerre, who have taken in 10 Haitian evacuees from Abaco.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Laguerre was born and raised in the Bahamas, but her parents are of Haitian descent. Despite not having enough money to pay their water bill, they have taken in 10 Haitian evacuees from four different families. They pool together what resources they can to grocery shop and cook for everybody in their compound.

“I wouldn’t say the floor is comfortable because it’s just cement,” she says. “We just let them put a sheet on the floor, and they sleep on the ground like that.”

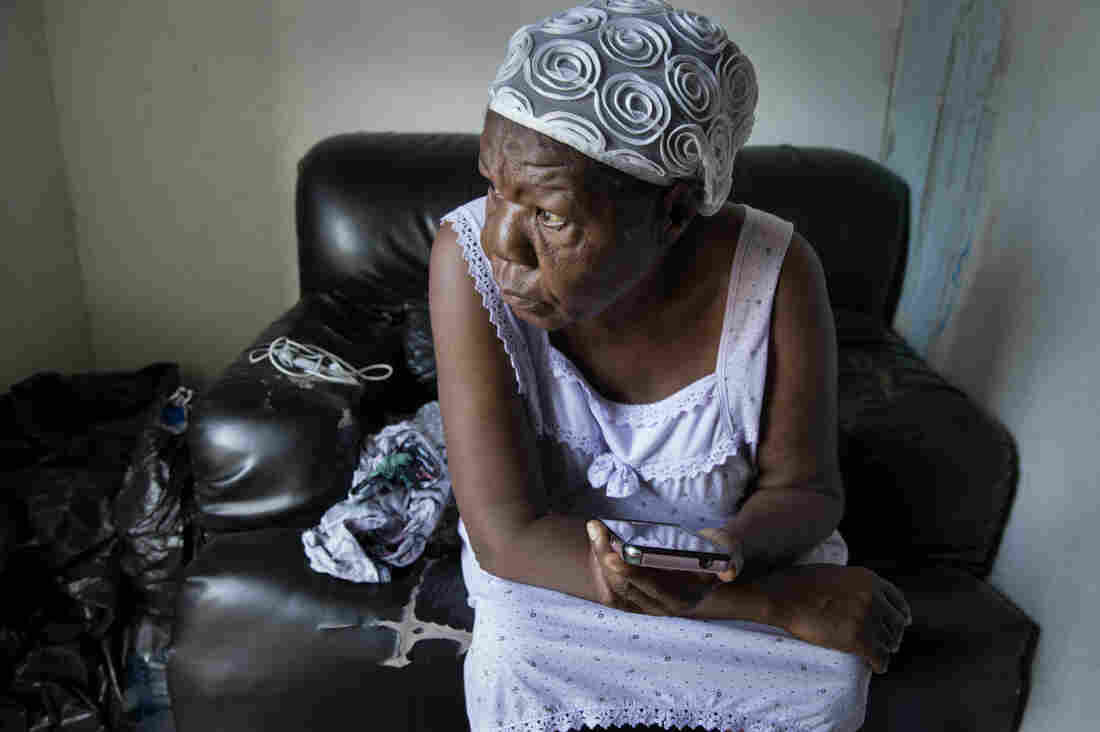

Abaco evacuee Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance shows a photo of herself during better times. LaFrance is one of thousands of Haitians who were displaced to Nassau after Hurricane Dorian.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

The families are still working through the physical and psychological effects of the storm. Lacieuse Timothee of Treasure Cay spent two days buried beneath debris before her sons found her. At the Laguerre home, she spends most of her time in bed. She says she is partially paralyzed, and the injuries around her feet have begun to turn black.

Evacuee Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance (right) tries to find an apartment to rent in Nassau. She’s being helped by family friends Benette Lutus (left) and Kenisher Lutus (center), who are with their 2-year-old daughter.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Laguerre and her parents do not have enough room in their home to keep welcoming guests. But they help those in need however they can. Recently, Laguerre referred a young mother to a friend’s house so she wouldn’t be left on the street with her child.

“I am not employed, but by the goodness of my heart — and I believe in God — this is God’s work here I am doing,” she says.

“Bahamians only” is printed on an advertisement for an apartment in Nassau. Some recent immigrants and others who have lived in the Bahamas for generations say that they face discrimination by their Bahamanian neighbors.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

For now, LaFrance’s family is living off the small amount of money that their relatives send from Haiti. They’re unsure when things will start to look up.

Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance (in print dress) meets about an apartment to rent in Nassau.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

“You can’t even sleep. You have nightmares. You feel like you’re still in the storm,” says LaFrance, more than a month after Hurricane Dorian made landfall. “If you see a little rain, you think the storm is coming again.”

Sherrine Petit Homme LaFrance weeps as she recounts how her relatives who live in Nassau turned their backs on her after her home was decimated by Hurricane Dorian.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

A month after Hurricane Dorian devastated the Bahamas, 14,000 people are still displaced and living in shelters like the Kendal Isaacs Gymnasium in Nassau. On Oct. 5, evacuees complained that the building temperature was so low that many spent time outdoors.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Lacieuse Timothee has sores that are turning black. A doctor diagnosed her with gangrene. She was injured after her home collapsed on her during the hurricane.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Bobson Timothee, 23, right, looks in on his mother, Lacieuse. who spends most of her time in bed.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

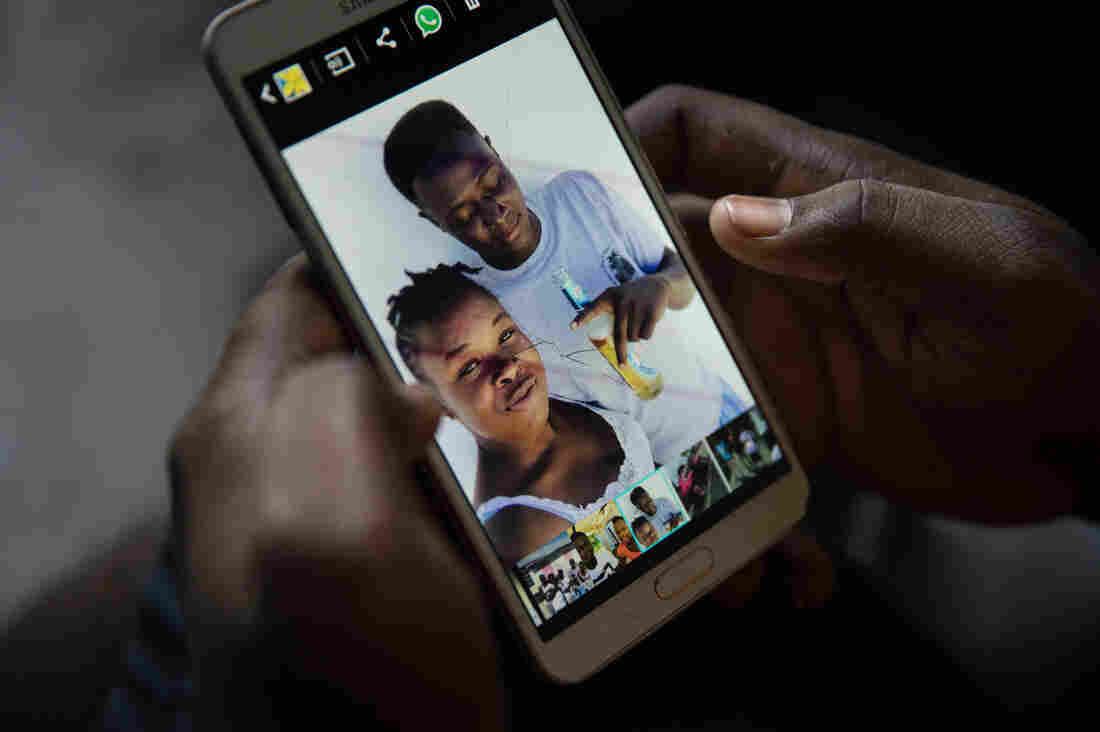

Bobson Timothee keeps a photo on his phone of himself with his best friend, Stephanie Forestal, who died during the storm.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Rolin Timothee sits at the doorway of the room in the home of China Laguerre where he and his wife, Lacieuse, stay as guests.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Ten evacuees from four different families are crowded into the six rooms of China Laguerre’s home.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Odne Laguerre (left) and evacuee Bobson Timothee pass the time while other evacuees play cards at the Laguerre home.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

The home of China Laguerre and her family has emerged as the headquarters of an ad hoc Haitian community support network.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

Abaco evacuee and Haitian immigrant to the Bahamas Micilia Etienne, 59, listens to news from Haiti while she and her family take shelter in China Laguerre’s home.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

The border patrol rounds up undocumented Haitian immigrants in Nassau on Sept. 30. Two days later, Prime Minister Hubert Minnis announced that Haitians in the Bahamas without documentation would be deported.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cheryl Diaz Meyer for NPR