A Fainting Spell After A Flu Shot Leads To $4,692 ER Visit

Matt Gleason fainted at work after getting a flu shot, so colleagues called 911 and an ambulance took him to the ER. Eight hours later, Gleason went home with a clean bill of health. Later still he got a hefty bill that wiped out his deductible.

Logan Cyrus for KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Logan Cyrus for KHN

Matt Gleason had skipped getting a flu shot for more than a decade.

But after suffering a nasty bout of the virus last winter, he decided to get vaccinated at his Charlotte, N.C., workplace in October. “It was super easy and free,” said Gleason, 39, a sales operations analyst.

That is, until Gleason fainted five minutes after getting the shot. Though he came to quickly and had a history of fainting, his colleagues called 911. And when the paramedics sat him up, he began vomiting. That symptom worried him enough to agree to go to the hospital in an ambulance.

Bill Of The Month

Read the other stories in our series here.

He spent the next eight hours at a nearby hospital — mostly in the emergency room waiting area. He had one consult with a doctor via teleconference as he was getting an electrocardiogram. He was feeling much better by the time he saw an in-person doctor, who ordered blood and urine tests and a chest X-ray.

All the tests to rule out a heart attack or other serious condition were negative, and Gleason was sent home at 10:30 p.m.

And then the bill came.

The patient: Matt Gleason, who works for Flexential, an information technology firm in Charlotte. He is married with two children.

Total bill: $4,692 for all the hospital care, including $2,961 for the ER admission fee, $400 for an EKG, $348 for a chest X-ray, $83 for a urinalysis and nearly $1,000 for various blood tests. Gleason’s insurer, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, negotiated discounts for the in-network hospital and reduced those costs to $3,711. Gleason is responsible for that entire amount because he had a $4,000 annual deductible. (The ambulance company and the ER doctor billed Gleason separately for their services, each about $1,300, but his out-of-pocket charge for each was $250 under his insurance.)

Service provider: Atrium Health Pineville (formerly called Carolinas HealthCare System-Pineville), a 235-bed nonprofit hospital in Charlotte and one of more than 40 hospitals owned by Atrium.

Medical service: On Oct. 4, Gleason was taken by ambulance to Atrium Health Pineville’s emergency room to be evaluated after briefly passing out and vomiting following a flu shot. He was given several tests, mostly to check for a heart attack.

What gives: Fainting after getting the flu vaccine or other shots is a well-described phenomenon in the medical literature. But once 911 is summoned, you could be facing an ER work-up. And in the U.S., that usually means big money.

The biggest part of Gleason’s bill — $2,961 — was the general ER fee. Atrium coded Gleason’s ER visit as a Level 5 — the second-highest and second-most expensive — on a 6-point scale. It is one step below the code for someone who has a gunshot wound or major injuries from a car accident. Gleason was told by the hospital that his admission was a Level 5 because he received at least three medical tests.

Gleason argued he should have paid a lower-level ER fee, considering his relatively mild symptoms and how he spent most of the eight hours in the ER waiting area.

The American Hospital Association, the American College of Emergency Physicians and other health groups devised criteria in 2000 to bring some uniformity to emergency room billing. The different levels reflect the varying amount of resources (equipment and supplies) the hospital uses for the particular ER level. Level 1 represents the lowest level of ER facility fees, while ER Level 6, or critical care, is the highest. Many hospitals have adopted the voluntary guidelines.

David McKenzie, reimbursement director at the American College of Emergency Physicians, said the guidelines were set up to help hospitals charge appropriately. Asked if hospitals have an incentive to perform extra tests to get patients to a higher-cost billing code, McKenzie said: “It’s not a perfect system. Hospitals have an incentive to do a CT exam, and taxi drivers have an incentive to take the long way home.”

The guidelines don’t determine the prices hospitals set for each ER level. Hospitals are free to set whatever prices they want as long as their system is consistent among patients, he said.

He said the multiple tests on Gleason suggest the hospital was worried he could be seriously ill. But he questioned why Gleason was told to stay in the ER waiting area for several hours if that was the case. It’s also not clear if Gleason’s history of fainting and overall good health was considered.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina said in a statement that the hospital “appears to have billed Gleason appropriately.” It noted the hospital reduced its costs by about $980 because of the insurer’s negotiated rates. But the insurer said it has no way to reduce the general ER admission fee.

“We work hard to negotiate discounts that reduce costs for our members, but costs are still far too high,” the insurer said. “This forces consumers to pay more out of pocket and drives up premiums.”

Gleason in fighting his bill actually got the hospital to send him its entire “chargemaster” price list for every code — a 250-page, double-sided document on paper. He was charged several hundred dollars more than the listed price for his Level 5 ER visit.

“In this specific example, the price of admission to the ER was more than $2,960. That was on top of more than $1,000 for the medical procedures actually performed. We won’t significantly bring down health care costs until we address the high prices like these,” BCBS-NC said in the statement.

John Hennessy, chief business development officer for WellRithms, a consulting firm that reviews bills for large employers, said the hospital charges are significantly higher than what Medicare pays in the Charlotte area, but those are the prices Gleason’s insurer has negotiated. “Seeing billed charges well in excess of what Medicare pays is nothing unusual,” Hennessy said.

He said the insurer most likely agreed to the higher charges to make sure it had the large hospital system in its network. Atrium is the biggest health system in North Carolina.

He said the coding “makes sense” because it meets the guidelines — even if that meant a nearly $4,000 bill for Gleason.

“The hospital has every right to collect it regardless if you or I think it’s a fair price,” he said.

Gleason reviews the chargemaster list of prices he received from Atrium Health. He questioned many of the charges on his bill after a trip to the ER.

Logan Cyrus for KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Logan Cyrus for KHN

Resolution: After Gleason appealed, Atrium Health reviewed the bill but didn’t make any changes. “I understand you may be frustrated with the cost of your visit; however, based on these findings, we are not able to make any adjustments to your account,” Josh Crawford, nurse manager for the hospital’s emergency department, wrote to Gleason on Nov. 15.

Atrium Health, in a statement to KHN and NPR, defended its care and charges as “appropriate.”

“The symptoms Mr. Gleason presented with could have been any number of things — some of them fatal,” the hospital said.

“Atrium Health has set criteria which determines at what level an [emergency department] visit is charged. In Mr. Gleason’s case, there were several variables that made this a Level 5 visit, including arriving by ambulance and three or more different departmental diagnostic tests.”

Gleason said the $3,700 hospital bill won’t bankrupt his family. “What it does is wipe out our savings,” he added.

The takeaway: Gleason, understandably, says he’s reluctant to get a flu shot in the future. But that’s not the best response. It’s important to know that fainting is a known reaction to shots and some people seem particularly prone. It’s best to sit or lie down when you get the vaccine, and wait five to 10 minutes before jumping up and returning to business.

Be aware, if you — or someone else — calls 911 for a health emergency, you are very likely to be taken to the hospital. You probably won’t have a choice of which one. And a hospital trip may not even be needed, so think before you call: “How do I feel?”

The medical professional who administered the shot might have suggested that calling 911 wasn’t a smart or needed response for a known side effect of a vaccine injection in a young person.

The emergency room is the most expensive place to seek care.

In hindsight, Gleason might have gone to an urgent care facility or called his primary care doctor, who could have evaluated him and run some tests at much lower prices, if needed.

But employers, hospitals and doctors regularly tell patients if they need immediate care to go to the ER, and hospitals often tout short waiting times in their ERs.

With high deductibles becoming more common, consumers need to be aware that a single trip to the hospital, especially an ER, could cost them thousands of dollars — even for symptoms that turn out to be nothing serious.

Alex Olgin of WFAE and Elisabeth Rosenthal of Kaiser Health News contributed contributed to the audio version of this story.

Do you have an exorbitant or baffling medical bill? Please share it with us and and tell us about your experience here.

Fear Of Deportation Or Green Card Denial Deters Some Parents From Getting Kids Care

Children of Mexican immigrants wait to receive a free health checkup inside a mobile clinic at the Mexican Consulate in Denver, Colo., in 2009. The Trump administration wants to ratchet up scrutiny of the use of social services by immigrants. That’s already led some worried parents to avoid family health care.

John Moore/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

John Moore/Getty Images

As U.S. immigration enforcement becomes stricter under the Trump administration, more immigrant families are cutting ties with health care services and other critical government programs, according to child advocates who work with these families.

In Texas, researchers studying the issue say it’s a major reason why more children are going without health insurance.

Ana, who lives in Central Texas with her husband and two children, has been increasingly hesitant to seek help from the government. In particular, she’s worried about getting help for her 9-year-old daughter, Sara, who was diagnosed with autism a few years ago.

Ana entered the country without documentation about 10 years ago, which is why NPR has agreed not to use her last name. Both her children were born in the U.S. and have been covered by Medicaid for years. But ever since President Trump took office, Ana has only been using the program for basics — such as checkups and vaccinations for the kids.

This decision to forgo care comes at a cost. Managing Sara’s behavior has been challenging, even after the diagnosis brought some clarity about what was going on. Sara acts out and has tantrums, sometimes in public places. Ana finds it difficult to soothe her daughter, and it’s become more awkward as Sara grows.

“To other people, Sara just seems spoiled or a brat,” Ana says.

After the diagnosis, Ana felt unsure about her next steps. She eventually went to a nonprofit in Austin that guides and supports parents whose children have disabilities. It’s called Vela (“candle” in Spanish).

At Vela, Ana learned about a range of services Sara could get access to via her Medicaid plan — including therapy to help the child communicate better.

However, the thought of asking for more government services for her daughter increased Ana’s anxiety. “I am looking for groups who are not associated with the government,” Ana explains.

Ana is in the middle of the long, expensive legal process of applying for permanent resident status, known informally as a “green card.” Recently, the Trump administration announced that it may tighten part of this process – the “public charge” assessment. The assessment scrutinizes how many government services a green card applicant currently uses — or might use later in life. If a person uses many government services, they could pose a net financial burden on the federal budget — or so goes the rationale. The government’s algorithms are complex, but “public charge” is part of the determination for who gets a green card and who doesn’t.

The rule change proposed by the Trump administration — which may not come to pass — has already led many applicants, or would-be applicants, to be wary of all government services, even those that wouldn’t affect their applications.

“I am afraid they will not give me a legal resident status,” Ana says.

Her husband already has a green card, and the couple is determined to not jeopardize Ana’s ongoing application. So they have decided — just to be safe — to avoid seeking any more help from the government. That’s even though their daughter, who is a citizen, needs more therapy than she’s getting right now.

“I feel bad that I have to do that,” Ana says.

She says she would love to treat her daughter’s autism, but has decided that there is nothing more important than getting that green card, in order to keep the family together in the U.S.

“I’m running into families that, when it’s time for re-enrollment or reapplication, they are pausing and they are questioning if they should,” says Nadine Rueb, a clinical social worker dealing with Ana’s case at Vela.

Reub says a range of fears are behind immigrants avoidance of government services. Some are staying under the radar to avoid immediate deportation. Others are more like Ana — they just want to be in the best position possible to finally get permanent legal status and move on with their lives.

“The climate of fear is so pervasive at this point, and there is so much misinformation out there,” says Cheasty Anderson, a Senior Policy Associate with the Children’s Defense Fund in Texas.

Anderson thinks the parents’ fears have led to an uptick in children going without health coverage in Texas.

A recent study from Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families found that one out of every five uninsured kids in the U.S. lives in Texas. And a big percentage of those uninsured children are Latino.

The report shows that after years of steady decline, the number (and percentage) of uninsured children in the U.S. increased in 2017, the first year of Trump’s presidency. Nationally, 5 percent of all kids are uninsured — and in Texas the rate rose to 10.7 percent, up from 9.8 percent in 2016.

Joan Alker, the author of the Georgetown report, says the Trump administration’s effort to crack down on both legal and illegal immigration is one of many factors driving up the uninsured rates. And it’s especially perceptible in Texas, where a quarter of children have a parent who is either undocumented, or who is trying to become a legal resident.

“For these mixed-status families, there is likely a heightened fear of interacting with the government, and this may be deterring them from signing up their eligible children up for government-sponsored health care,” Alker said in a phone call with reporters in November, when the report was released.

Anderson says the repercussions fall hardest on kids with disabilities — kids who need services.

“Texas is proud to be Texas in so many ways, but this is one way in which we are failing ourselves,” she says.

From the perspective of Reub, a disability rights specialist, timing is an essential issue for these children.

“The sooner you catch [the diagnosis or condition], the sooner you support the child [and] the sooner you support the family,” Reub says. “I think it’s just a win-win for everybody. You are supporting the emotions of the family, and then that supports the child.”

For now, Ana says she’s relying on the services offered by her daughter’s public school — which aren’t counted in the federal government’s “public charge” assessment. And she’ll keep doing that until she gets that green card.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with KUT and Kaiser Health News.

Steep Climb In Benzodiazepine Prescribing By Primary Care Doctors

The drugs clonazepam and diazepam are both benzodiazepines — and better known by the brand names Klonopin and Valium. The drug class also includes Ativan, Librium and Halcion.

Bloomberg/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Bloomberg/Getty Images

The percentage of outpatient medical visits that led to a benzodiazepine prescription doubled between 2003 and 2015, according to a study published Friday. And about half those prescriptions came from primary care physicians.

This class of drugs includes the commonly used medications Valium, Ativan and Xanax. While benzodiazepines are mostly prescribed for anxiety, insomnia and seizures, the study found that the biggest rise in prescriptions during this time period was for back pain and other types of chronic pain. The findings appear online in JAMA Network Open.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

And while benzodiazepines are best for short-term use, according to physicians, the new study found that long-term use of these drugs has also risen. From 2005 to 2015, continuing prescriptions increased by 50 percent.

Long term use of the drugs can cause physical dependence, addiction and death from overdose.

“I don’t think people realize that benzodiazepines share many of the same characteristics of opioids,” says Dr. Sumit Agarwal, an internist, primary care physician and researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and one of the authors of the new study.

“They are addictive,” he says. “They cause you to have slower breathing; they cause you to be altered in terms of mental status. And then, eventually, [they] can cause overdose and deaths.”

Previous studies have shown a nearly eightfold rise in mortality rates from overdoses involving benzodiazepines — from 0.6 in 100,000 people in 1999 to 4.4 in 2016.

“That’s somewhere around 10,000 to 12,000 deaths at the hands of benzodiazepines,” says Agarwal. “This rise is happening quietly, outside of the public eye.”

And according to a recent report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the overdose mortality rate for women between the ages of 30 and 64 increased by 830 percent between 1996 and 2017.

“Women are more likely to be prescribed these medications,” Agarwal says. “Women are more likely to come in to the clinic to be treated for anxiety and depression, and benzodiazepines tend to be one of the medications we reach to.”

“The study highlights that we have a very serious problem with benzodiazepines,” says Anne Lembke, an associate professor of psychiatry and medical director of addiction medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine. She wasn’t involved in the new study.

“I am concerned that our national focus on opioids has hidden the problem related to benzodiazepines — that’s our next frontier,” says Dr. Joanna Starrels, as associate professor at the department of medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. She wasn’t involved in the new study, but co-authored a 2016 study that found a rise in prescription rates and overdose deaths from this class of drugs between 1996 and 2013.

Lembke notes that the biggest rise in outpatient visits that led to benzodiazepine prescriptions were from primary care physicians and not psychiatrists.

“I think the big message here is that primary care doctors are really left with burden of dealing, not only with chronic pain and opioid prescription, but also benzodiazepine prescriptions,” she says.

The trends, she adds, reflect “the incredible burden of care on primary care physicians, who are given little time, or resources” to handle a high volume of pain patients with complex conditions.

“That’s partly what got us into the opioid epidemic in the first place,” Lembke notes.

“Generally speaking primary care physicians have not received the training that they need to prescribe medications that have such high risk for addiction or overdose,” says Starrels.

“Primary care doctors,” she says, “are the frontline providers. “And in many settings, particularly in rural areas, we may be the only providers. So we end up needing to treat conditions where specialists may be better trained — like chronic pain, addiction and anxiety.”

Given the rise in benzodiazepine prescriptions for back pain and chronic pain, “it may be that benzodiazepines are taking the place of opioids,” says Lembke.

However, Starrels cautions that the new study couldn’t determine whether the patients who were treated for back or chronic pain were prescribed a benzodiazepine for their pain. It’s also possible they were prescribed these medications for anxiety or insomnia in addition to being treated for pain.

The new study also found that the co-prescribing of benzodiazepines with opioids has risen during this time period. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, says Lembke.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

“What we don’t want doctors to do is cut patients off of opioids,” she says. “That’s neither humane nor medically the right path. Some of these co-prescribing may be because doctors are tapering patients off of opioids.”

But co-prescribing these two kinds of medications can be dangerous. “They both slow down the central nervous system in complementary ways [that] increase the risk of overdose deaths,” says Starrels. “It is dangerous — and generally advised not to prescribe together.”

In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warned doctors about the dangers of prescribing opioids and anxiety medications together.

Agarwal says that warning may have had a positive effect on prescription rates of these anxiety meds. “Next couple of years of data will be very telling,” he says.

Starrels notes that benzodiazepines have not been shown to be effective for chronic pain. And there’s more effective treatment for insomnia, she says.

For example, a form of talk therapy has been shown to be one of the most effective treatments for insomnia. And simply practicing better sleep hygiene can make a big difference, she says.

Physicians who want to move patients off their long term use of benzodiazepines, should do it slowly over time, Starrels cautions. “It has to be slow and medically monitored over time,” she says, because “sudden withdrawal can be fatal.”

She says primary care doctors should get better guidelines for prescribing these drugs, just as there are CDC guidelines for opioid prescription.

“People have started calling this ‘our other prescription drug problem’ — the first one being opioids, but this one’s flying under the radar,” Agarwal says. “It would be great if we address it before it becomes an epidemic — if there isn’t already one.”

Trump Seeks Action To Stop Surprise Medical Bills

Dr. Paul Davis, whose daughter, Elizabeth Moreno, was billed $17,850 for a urine test and featured in KHN-NPR’s Bill of the Month series, was among the guests invited to the White House on Wednesday to discuss surprise medical bills with President Trump.

Julia Robinson for KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Robinson for KHN

President Trump instructed administration officials Wednesday to investigate how to prevent surprise medical bills, broadening his focus on drug prices to include other issues of price transparency in health care.

Flanked by patients and other guests invited to the White House to share their stories of unexpected and outrageous bills, Trump directed his health secretary, Alex Azar, and labor secretary, Alex Acosta, to work on a solution, several attendees said.

“The pricing is hurting patients, and we’ve stopped a lot of it, but we’re going to stop all of it,” Trump said during a roundtable discussion when reporters were briefly allowed into the otherwise closed-door meeting.

David Silverstein, the founder of a Colorado-based nonprofit called Broken Healthcare who attended, said Trump struck an aggressive tone, calling for a solution with “the biggest teeth you can find.”

“Reading the tea leaves, I think there’s big change coming,” Silverstein said.

Surprise billing, or the practice of charging patients for care that is more expensive than anticipated or isn’t covered by their insurance, has received a flood of attention in the past year, particularly as Kaiser Health News, NPR, Vox and other news organizations have undertaken investigations into patients’ most outrageous medical bills.

Attendees said the 10 invited guests — patients as well as doctors — were given an opportunity to tell their story, though Trump didn’t stay to hear all of them during the roughly hourlong gathering.

The group included Paul Davis, a retired doctor from Findlay, Ohio, whose daughter’s experience with a $17,850 bill for a urine test after back surgery was detailed in February 2018 in KHN-NPR’s first Bill of the Month feature.

Davis’ daughter, Elizabeth Moreno, was a college student in Texas when she had spinal surgery to remedy debilitating back pain. After the surgery, she was asked to provide a urine sample and later received a bill from an out-of-network lab in Houston that tested it.

Such tests rarely cost more than $200, a fraction of what the lab charged Moreno and her insurance company. But fearing damage to his daughter’s credit, Davis paid the lab $5,000 and filed a complaint with the Texas attorney general’s office, alleging “price gouging of staggering proportions.”

Davis said White House officials made it clear that price transparency is a “high priority” for Trump, and while they didn’t see eye to eye on every subject, he said he was struck by the administration’s sincerity.

“These people seemed earnest in wanting to do something constructive to fix this,” Davis said.

Dr. Martin Makary, a professor of surgery and health policy at Johns Hopkins University who has written about transparency in health care and attended the meeting, said it was a good opportunity for the White House to hear firsthand about a serious and widespread issue.

“This is how most of America lives, and [Americans are] getting hammered,” he said.

Trump has often railed against high prescription drug prices but has said less about other problems with the nation’s health care system. In October, shortly before the midterm elections, he unveiled a proposal to tie the price Medicare pays for some drugs to the prices paid for the same drugs overseas, for example.

Trump, Azar and Acosta said efforts to control costs in health care were yielding positive results, discussing in particular the expansion of association health plans and the new requirement that hospitals post their list prices online. The president also took credit for the recent increase in generic drug approvals, which he said would help lower drug prices.

Discussing the partial government shutdown, Trump said Americans “want to see what we’re doing, like today we lowered prescription drug prices, first time in 50 years,” according to a White House pool report.

Trump appeared to be referring to a recent claim by the White House Council of Economic Advisers that prescription drug prices fell last year.

However, as STAT pointed out in a recent fact check, the report from which that claim was gleaned said “growth in relative drug prices has slowed since January 2017,” not that there was an overall decrease in prices.

Annual increases in overall drug spending have leveled off as pharmaceutical companies have released fewer blockbuster drugs, patents have expired on brand-name drugs and the waning effect of a spike driven by the release of astronomically expensive drugs to treat hepatitis C.

Drugmakers were also wary of increasing their prices in the midst of growing political pressure, though the pace of increases has risen recently.

Since Democrats seized control of the House of Representatives this month, party leaders have rushed to announce investigations and schedule hearings dealing with health care, focusing in particular on drug costs and protections for those with preexisting conditions.

Last week, the House Oversight Committee announced a “sweeping” investigation into drug prices, pointing to an AARP report saying the vast majority of brand-name drugs had more than doubled in price between 2005 and 2017.

Kaiser Health News correspondents Shefali Luthra and Jay Hancock contributed to this report. You can follow Emmarie Huetteman on Twitter: @emmarieDC.

California Doctors Alarmed As State Links Their Opioid Prescriptions to Deaths

When a former patient died from a lethal combination of methadone and Benadryl, Dr. Ako Jacintho got a letter from the state medical board.

Whitney Hayward/Portland Press Herald/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Whitney Hayward/Portland Press Herald/Getty Images

About a year ago, Dr. Ako Jacintho of San Francisco returned home from traveling to find a letter from the state medical board waiting for him.

The letter explained that a patient he had treated died in 2012 from taking a toxic cocktail of methadone and Benadryl — and Jacintho was the doctor who wrote the patient’s last prescription for methadone. He had two weeks to respond with a written summary of the care he had provided, and a certified copy of the patient’s medical record. He faced fines of $1,000 per day if he didn’t comply.

“I was horrified,” Jacintho says. He hadn’t known that the patient had died. “I became overwrought with sadness. And I was really just surprised that this had happened to this patient.”

The letter was one of more than 500 sent to doctors in recent years throughout the state, all part of the California medical board’s Death Certificate Project. The board typically investigates doctors in response to patient complaints, but with this project, it proactively collected almost 3,000 death certificates of people who died of opioid overdoses, then cross-referenced those with the state’s drug prescription database.

Investigators are going back three years to identify any doctors who may have prescribed the drugs inappropriately, even if it was not the fatal dose, and send them letters. Doctors who are found to have violated state law face public reprimands, probation, or even revocation of their medical licenses.

When Jacintho received his letter, his first reaction was grief. But then he grew afraid, then indignant. The letter seemed to presume he did something wrong — it used words like “complaint” and “allegation.” But when Jacintho reviewed the patient’s medical charts, he was convinced he didn’t.

Dr. Ako Jacintho was horrified to learn that a patient of his had died of an overdose and was surprised when the state started investigating him.

April Dembosky/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

April Dembosky/KQED

“This person had intractable pain,” Jacintho says, and at the time, methadone was a preferred treatment. Methadone is long-acting, and was considered to have less potential for addiction than other opioids. In particular, Jacintho says he takes issue with the board’s choice of words in the letter: “over-prescribing,” and “toxic levels.”

“Toxicity is a very subjective word,” he says. “What’s a toxic level for someone may not be a toxic level for someone else.”

It wasn’t until 2016 that the CDC issued guidelines for prescribing opioids, telling doctors to start with low dosages and increase slowly. And when possible, use ibuprofen instead.

But, back in 2012, doctors like Jacintho were being admonished to never leave a patient in pain. The California medical board’s own guidelines from 2013 advised doctors that for certain types of pain, opioids were the cornerstone of treatment and should be pursued vigorously.

“It actually says that no physician will receive disciplinary action for prescribing opioids to patients with intractable pain,” Jacintho says.

But now the medical board is using death certificates from 2012 and 2013 to discipline doctors.

The timing of the investigation really bothers Jacintho, because in the six years since his patient died, he’s totally revamped his practice. As a family doctor, he saw the opioid crisis coming. He had patients asking for more, stronger drugs, even though their pain stayed the same. So he switched gears, went back into training and got certified as an addiction specialist.

“If they’re looking for clinicians who are overprescribing, I’m the wrong doctor,” he says.

The executive director of the medical board, Kim Kirchmeyer says medical investigators take career changes like this into account, and they review medical records according to the standard of care that was in place at the time.

“We understand that just because a patient has overdosed that that doesn’t mean that the care and treatment provided was not appropriate,” she says. But anytime there may have been a violation of the law, she adds, “we do need to look into it.”

The board is only punishing doctors who actually broke the law, she says — those with a clear and repeated pattern of inappropriate prescribing.

“Individuals were prescribing drugs without even performing a history and physical exam,” she says. These doctors never did any kind of testing, they didn’t provide informed consent. “They don’t have a treatment plan or objectives. They just continue to prescribe and prescribe.”

Investigators have so far completed investigations for about half of the 500 doctors originally identified as possibly deviating from the standard of care. The majority were cleared of any wrongdoing, and the board filed formal accusations against 25 doctors.

But there are hundreds of doctors who are still waiting, more than a year later, to learn their fate.

Ultimately, the medical board is a consumer protection agency, Kirchmeyer says, and this is about patient safety, not doctors’ comfort. “If we save one life through this project, that is meeting the mission of the board, and that makes this project so worth it,” she says.

But it’s unclear if the overall effect of the project will be good for patients. Some doctors, including Jacintho, have been so frightened by the letters that they’ve lowered their patients’ opioid doses or cut them off completely. Some doctors are telling their chronic pain patients to find another doctor, according to the California Medical Association. This carries a whole new set of risks.

“It’s like leaving a pair of scissors in an abdomen after surgery,” says Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of substance use research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “If you’re just going to discontinue opioids, basically you’re ripping out the scissors and telling the person: ‘Good luck.’ Let them deal with the intestinal perforation on their own.”

The CDC’s 2016 guidelines on how to prescribe opioids are for patients who have never taken them before. But they include virtually no guidance on how to taper down doses for chronic pain patients who have already been taking high doses of opioids for many years.

Preliminary research from the San Francisco Department of Public Health suggests some patients who are weaned off long-term prescription opioids are twice as likely to turn to street drugs. That increases risk of overdose.

“Scaring providers into not prescribing opioids, I think that is not the ethically appropriate way to go forward,” Coffin says of the California Death Certificate Project.

Doctors in North Carolina reacted similarly — refusing to treat chronic pain patients — when the medical board there began proactively investigating doctors who had prescribed high levels of opioids, or who had two patients die of an overdose in the previous year.

A federal prosecutor in Massachusetts also sent letters to doctors who had prescribed opioids within 60 days of a patient’s death. While those letters were intended to be a “warning,” rather than notice of an investigation, they also sparked fear among doctors.

It was never the California medical board’s intention for doctors to simply stop prescribing opioids, Kirchmeyer explains, and it doesn’t want that outcome. She says board members have already learned some lessons on how to improve their approach: They’ve rewritten the letters so they’re less accusatory. And, they know they have to move faster with the investigations.

But the board is committed to the project. Kirchmeyer says after the board finishes examining the 2013 death certificates, it will start working on 2014.

House Democrats' Focus On Abortion Could Stymie Work With Senate

At an October news conference, the Congressional Pro-Choice Caucus called on President Trump to reverse the administration’s moves to limit women’s access to birth control. Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Colo., spoke at the lectern during the event on Capitol Hill.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Alex Wong/Getty Images

For the first time since the Supreme Court legalized abortion nationwide in its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the House of Representatives has a majority supporting abortion rights. And that majority is already making its position felt, setting up what could be a series of long and drawn-out fights with a Senate opposed to abortion and stalling what could otherwise be bipartisan bills.

Democrats have held majorities in the House for more than half of the years since abortion became a national political issue in the 1970s, but those majorities included a significant number of Democrats who opposed abortion or had mixed voting records on the issue. A fight among Democrats over abortion very nearly derailed the Affordable Care Act as it was becoming law in 2010.

This new Democratic majority is more liberal — at least on reproductive rights for women — than its predecessors. “I am so excited about this new class,” Rep. Diana DeGette, a Colorado Democrat and co-chair of the Congressional Pro-Choice Caucus, told reporters at a Jan. 15 news conference. “We are systematically going to reverse these restrictions on women’s health care.”

Indeed, the House has taken its first steps to do just that. On its first day of work Jan. 3, House Democrats passed a spending bill to reopen the government that would also have reversed President Trump’s restrictions on funding for international aid organizations that perform abortions or support abortion rights. As one of his first acts as president, Trump re-imposed the so-called Mexico City Policy originally implemented in the 1980s by President Ronald Reagan.

But the Senate, where Republicans still hold a slim majority, is not budging. If anything, Republican Senate leaders are trying to push further on abortion. On Thursday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell called a floor vote on a bill that would ban any federal funding of abortion or help fund insurance that covers abortion costs. Congress routinely adds the “Hyde Amendment” — a rider to the spending bill for the Department of Health and Human Services to bar federal abortion funding in most cases for Medicaid and other health programs — but McConnell’s legislation would have made the provision permanent and government-wide.

When the House was under GOP control, it passed similar measures repeatedly, but those bills haven’t been able to emerge from the Senate, where 60 votes are required. In the end, McConnell’s bill Thursday got 48 votes, 12 short of the number needed to move to a full Senate debate.

Organizations that oppose abortion were thrilled, even though the bill failed to advance.

“By voting on the No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion Act, the pro-life majority in the Senate is showing they’ll be a brick wall when it comes to trying to force taxpayers to pay for abortion on demand,” says a statement from the Susan B. Anthony List.

The Senate action Thursday was clearly aimed not just at House Democrats’ boast that they would vote to overturn existing abortion restrictions, but also at the annual anti-abortion “March for Life” held in Washington on Friday.

“I welcome all of the marchers with gratitude,” said McConnell in his brief

remarks on the bill, noting that they “will speak with one voice on behalf of those who cannot speak for themselves.”

But these first two votes are just a taste of what is likely to come.

At a breakfast meeting with reporters Jan. 16, DeGette, newly installed as chair of the oversight subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said that reproductive issues would be a highlight of her agenda.

Meanwhile, Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif., the other co-chair of the Pro-Choice Caucus, and Nita Lowey, D-N.Y., the first female chair of the House Appropriations Committee, announced they will introduce legislation to permanently eliminate both the Hyde Amendment and the Mexico City Policy.

In an odd twist, the abortion language in the Mexico City Policy bill passed by the House this month was taken directly from a version approved last June by the Senate Appropriations Committee. Republican Sens. Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, who generally support abortion rights, joined with the committee’s Democrats to approve an amendment overturning the policy in the spending bill for the State Department and other agencies. The full Senate never voted on that bill.

Still, neither side is likely to advance their cause in Congress over the next two years. The Republican leadership in the Senate can block any House-passed bills lifting abortion restrictions. But the Senate, while nominally opposed to abortion rights, doesn’t include 60 members who would vote to advance further restrictions.

Where things get interesting is if either chamber tries to strong-arm the other by adding abortion-related language it knows will be unacceptable to the other side.

That is exactly what happened in 2018, when the Senate was poised to pass a bipartisan bill to help stabilize the Affordable Care Act‘s insurance exchanges. House and Senate Republicans proposed a version of the bill — but with the inclusion of a permanent ban on abortion funding. Democrats objected and the bill died.

Sen. Patty Murray,D-Wash., who was one of the senators engineering the original bipartisan effort, said at the time, “This partisan bill … pulled the most worn page out of the Republican ideological playbook: making extreme, political attacks on women’s health care.”

It is not hard to imagine how such an abortion rider could be used by either side to squeeze the other, as Republicans and Democrats tentatively start to work together on health issues such as prescription drug prices and surprise out-of-pocket bills.

Abortion-related impasses could also stall progress on annual spending bills if House Democrats keep their vow to eliminate current restrictions like those limiting self-paid abortions for servicewomen or imposing further limits on international aid.

Abortion fights on unrelated bills are almost a certainty in the coming Congress, said Ross Baker, a professor of political science at Rutgers University. He noted that abortion not only complicates health bills, but also sank a major bankruptcy bill in the early 2000s.

“The only question is how it will emerge,” he said. “And it will emerge.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. You can follow Julie Rovner on Twitter: @jrovner.

Medical Students Push For More LGBT Health Training To Address Disparities

Sarah Spiegel, a third-year student at New York Medical College, pushed for more education on LGBT health issues for students.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

When Sarah Spiegel was in her first year at New York Medical College in 2016, she sat in a lecture hall watching a BuzzFeed video about what it’s like to be an intersex or a transgender person.

“It was a good video, but it felt inadequate for the education of a class of medical students, soon to be doctors,” says Spiegel, now in her third year of medical school.

The video, paired with a 30-minute lecture on sexual orientation, was the only LGBT-focused information Spiegel and her fellow classmates received in their foundational course.

“It’s not adequate,” Spiegel remembers thinking. By her second year, after she became president of the school’s LGBT Advocacy in Medicine Club, she rallied a group of her peers to approach the administration about the lack of LGBT content in the curriculum.

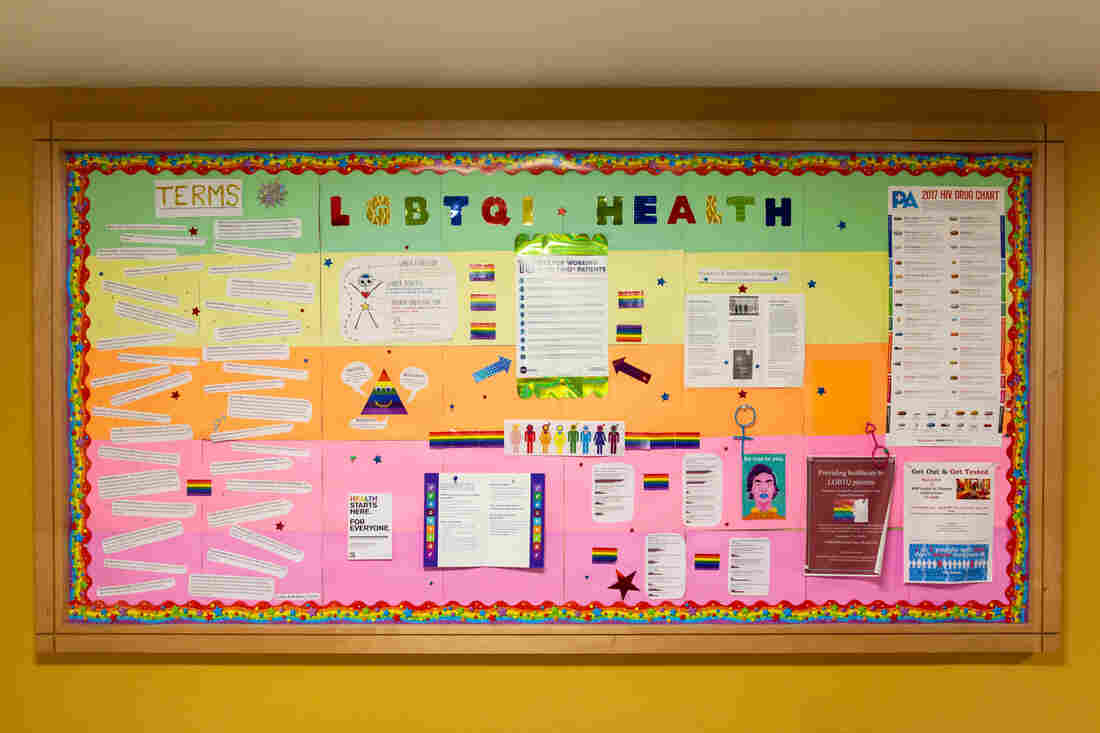

Spiegel and her friends created an LGBTQI health board of information which hangs in a hallway on campus at New York Medical College.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

Spiegel says administrators were “amazingly receptive” to her presentation, and she quickly gained student and faculty allies. As a result, the school went from one and a half hours of LGBT-focused content in the curriculum to seven hours within a matter of two years, according to Spiegel. Spiegel says she doesn’t think the change would have happened had the students not pushed for it.

According to a number of studies, medical schools do a poor job of preparing future doctors to understand the LGBT population’s unique needs and health risks. And, a 2017 survey of students at Boston University School of Medicine found their knowledge of transgender and intersex health to be lesser than that of LGB health.

Meanwhile, LGBT people — and transgender people in particular – face disproportionately high rates of mental illness, HIV, unemployment, poverty, and harassment, according to Healthy People 2020, an initiative of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. And a poll conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found 1 in 5 LGBT adults has avoided medical care due to fear of discrimination.

“The health of disparity populations is something that really should be the focus of health profession students,” says Dr. Madeline Deutsch, an associate professor of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Deutsch directs UCSF’s Transgender Care program, and she says medical schools already do a fairly good job of addressing some disparities, like those based on race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status.

But, she says, “Sexual and gender minorities have historically been not viewed as a key population, and that’s unfortunate because of the size of the population, and because of the extent of the disparities that the population faces.” (About 0.6 percent of the U.S. population – or 1.4 million adults – identifies as transgender.)

The extent of LGBT education medical students receive varies greatly, but a 2011 study found that the median time spent on LGBT health was five hours. The topics most frequently addressed include sexual orientation, safe sex, and gender identity, whereas transgender-specific issues, including gender transitioning, were most often ignored. And some medical students receive no LGBT education at all.

“There’s not really a consistent curriculum that exists around this content,” says Deutsch.

As a result, physicians often feel inadequately trained to care for LGBT patients. In a 2018 survey sent out to 658 students at New England medical schools, around 80 percent of respondents said they felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” with the medical treatment of gender and sexual minority patients.

Even at UCSF, which has long been at the forefront of LGBT health care, Deutsch says there’s still a need to insert more transgender health care into the mandatory curriculum. Right now, when medical schools teach about LGBT health issues, it’s usually through special elective courses or lectures taught at night or during lunch, and often by the students themselves.

“How do we take it out of the lunchtime unit?” asks Jessica Halem, the LGBT program director at Harvard Medical School. That question drives Harvard Medical School’s new Sexual and Gender Minorities Health Equity Initiative, a three-year plan to assess the core medical school curriculum and to identify opportunities to better instruct on the health of sexual and gender minorities.

“Students are getting the information. But some of them are having to do a lot of extra work to get that during their medical school experience,” says Halem.

The Harvard initiative, announced in December 2018, has been ongoing for about six months, says Halem, thanks to a $1.5 million gift from Perry Cohen, a transgender man. According to Halem, Cohen hopes that Harvard’s learnings will be shared with medical schools across the country, especially with ones with less robust LGBT health education programs.

Studies have shown that when medical students learn about transgender health issues, they feel better equipped to treat transgender patients. For example, when Boston University School of Medicine added transgender health content to a second-year endocrinology course, students reported a nearly 70 percent decrease in discomfort with providing transgender care.

And now, Halem says, each incoming class at Harvard Medical School is increasingly adamant that they learn about LGBT health.

“The main first driver truly was medical students organizing and saying ‘Hey, I need the curriculum to reflect the kind of medicine that I came here to study,’ ” Halem says.

The amount of LGBT education medical students receive varies greatly. A 2015 study found that, on average, medical students receive five hours of LGBT-focused education. The curriculum at New York Medical College went from an hour and a half of LGBT topics in health care to over seven hours.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

Those were the thoughts running through Spiegel’s head in her own preclinical years at New York Medical College. Shortly after becoming the president of her school’s LGBT health club, she joined The American Medical Student Association’s Gender and Sexuality Committee as the LGBTQ Advocacy Coordinator to bring curricular change to other medical schools in the New York area.

Conversations with her transgender partner also inspired Spiegel to introduce more trans-specific topics into her school’s curriculum.

“His experience definitely varied by how much providers knew,” Spiegel says. It was often as simple as getting his pronouns correct, she says, and even then, the same doctors’ office would mess that up again and again.

Spiegel says in the past couple of years, certain disciplines have added trans-focused topics into their specialties. In the school’s behavioral health unit, for example, professors have started to address how doctors can diagnose gender dysphoria – when a person feels their assigned gender does not align with their gender identity – in their lectures.

By contrast, some disciplines have been more hesitant to change, or add content to, their existing curriculum. Spiegel’s student task-force had more difficulty influencing the pharmacology department, for example. That’s the content area where hormone therapy might be taught, Spiegel says.

One course includes a lecture about the endocrine system, Spiegel says, when the professor talks about a drug to treat precocious, or early puberty. That drug can also be used for kids undergoing transgender hormone therapy. Therefore, Spiegel says, including transgender health in the lecture might be a matter of just saying an extra sentence.

“There’s an opportunity there – they would just have to mention that it could also be used for transgender kids,” says Spiegel.

But the professor says this secondary use of the drug was “off the book,” and thus, he wouldn’t include it in his lecture. So Spiegel researched the drug herself, and sent the professor the Endocrine Society’s guidebook that talked about how the drug can be used for transgender patients. He began including the information in his lectures.

Spiegel says her interactions with this professor exemplify the challenges that medical students all over the country face when trying to introduce changes to their schools’ curricula.

“We’re getting there, but it’s slow,” says Spiegel.

How Much Is That CAT Scan? Now You Can Check (If You Know Billing Codes)

Starting this month, hospitals must publish prices for procedures and services online. Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal of Kaiser Health News tells NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro it’s not very user friendly — yet.

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

If you go to buy a car, there’s a good chance you’ll do some comparison shopping. But if you’re going into a hospital for a CAT scan or a hip replacement, for example, good luck. That is until this month, when all hospitals were required by law to make public a list of procedures and prices and post them on the Internet. The new requirement is meant to help patients navigate the nation’s confusing health care billing practices. So how well are hospitals doing? Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal is the editor-in-chief of Kaiser Health News. And she has been advocating for something like this for a very long time. And she joins us in the studio. Welcome.

ELISABETH ROSENTHAL: Thanks for having me.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: So are hospitals complying with the new law?

ROSENTHAL: Well, yes. They’re complying. But basically, what they’ve done at this point is kind of a data dump. You know, here’s our price list. It’s hundreds of pages long. It’s in codes. It’s in abbreviations. So it’s not in a very user-friendly form, to say the least. But it’s an important first step.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: OK. Is it actually possible to comparison shop? And what are the pitfalls?

ROSENTHAL: I trained as a physician. I’ve spent, you know, decades covering health care. So I understand what these abbreviations mean. So I can decode some of them. And when you decode some of them, you see some crazy prices. Like, a bag of IV saline at one hospital could be $30 and at another $1,000. So I look through these all the time. And I see things that stand my hair on end.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: We had one of our editors who has been dealing with an ill relative – she went on the Washington State Hospital Association’s website. And she said it was quite easy to comparison shop. It is happening. What are the caveats?

ROSENTHAL: Well, the pitfalls – and I think the problem has been a lot of states have made efforts to say, you need to make it easy for patients to comparison shop. So they’ll say, OK, give us a price for an appendectomy – all in. The problem is that every hospital calculates that differently. Some will just say oh, well, that’s the OR fee. And the – and then you say well, you know, you said it was $4,000 on your website. And then the hospital goes, oh, well, that didn’t include the anesthesiologist or the scalpel. You know, it’s literally at that level.

So what we see at Kaiser Health News is that people are often caught in the dark with this. They say, well, I tried to comparison shop. And I went to this hospital. And they told me it was going to be $4,000. And then I get a bill for $25,000. So what gives? So I think the effort here is a starting point to say we need apples to apples comparisons.

Now, the data that’s been released right now is not very useful for patients generally for an appendectomy or for heart surgery because that’s a big procedure. And you’d have to add up hundreds of line items. But if you’re looking for something simple, like an MRI of your knee, you know, and you’re willing to put in the time to decode a chargemaster, that is pretty comparable – one institution to another. So it’s useful in a small way now. But I suspect having this data out there will make it useful in a much bigger way over time.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Some hospital administrators have said that the new law makes things more confusing because the prices don’t account for a person’s health care insurance or the fact that insurers pay a discounted rate. What do you say to that?

ROSENTHAL: Hospitals have made every argument under the sun to not release these prices. They’ve said, well, nobody pays that. It depends on your insurance. You know – but it’s all kind of smoke and mirrors to me. You know, yes, maybe it’s not directly relevant. But show us your prices. Show us what you’re charging. When I go to a hotel, I may be only paying $100 a night. But I can see on every website that the normal price for that room, the list price, is $500 or whatever. So these are list prices. They’re not directly relevant. But we deserve to know them. And hospitals should not be trying to hide them.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal is the author of “An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became A Big Business And How You Can Take It Back (ph).” Thank you so much.

ROSENTHAL: Thanks for having me.

(SOUNDBITE OF D.P. KAUFMAN’S “BRAVERY”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Federal Shutdown Has Meant Steep Health Bills For Some Families

Demonstrators affiliated with the National Air Traffic Controllers Association protested the federal shutdown at a Capitol Hill rally earlier this month in Washington, D.C.

Alex Wroblewski/Bloomberg/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Alex Wroblewski/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Joseph Daskalakis’ son Oliver was born on New Year’s Eve, a little over a week into the current government shutdown, and about 10 weeks before he was expected.

The prematurely born baby ended up in a specialized neonatal intensive care unit, the only one near the family’s home in Lakeville, Minn., that could care for him.

But Daskalakis, who works as an air traffic controller outside Minneapolis, has an additional worry: The hospital where his newborn son is being treated is not part of his current insurer’s network and the partial government shutdown prevents Daskalakis from filing the paperwork necessary to switch insurers, as he would otherwise be allowed to do.

As a result, he could be on the hook for a hefty bill — all the while not receiving pay. Daskalakis is just one example of federal employees for whom being unable to make changes to their health plans really matters.

Although the estimated 800,000 government workers affected by the shutdown won’t lose their health insurance, an unknown number are in limbo like Daskalakis — unable to add family members such as spouses, newborns or adopted children to an existing health plan; unable to change insurers because of unforeseen circumstances; or unable deal with other issues that might arise.

“With 800,000 employees out there, I imagine that this is not a one-off event,” says Dan Blair, who served as both acting director and deputy director of the federal Office of Personnel Management during the early 2000s and is now senior counselor at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “The longer this goes on, the more we will see these types of occurrences.”

While little Oliver Daskalakis is getting stronger every day — he’s now out of the ICU, according to his father’s local air traffic union representative — it’s unclear how the situation will affect his family’s finances.

That’s because out-of-network charges are generally far higher than being in-network, and NICU care is enormously expensive,no matter what. Those bills could add up, especially as the family’s current insurance plan has an out-of-pocket maximum of $12,000 annually. Because Oliver was born before the new year, the family could face that amount twice — for 2018 and for 2019.

And Daskalakis still isn’t getting paid.

“I don’t know when I’ll be able to change my insurance, or when I’ll get paid again,” Daskalakis wrote to Sen. Tina Smith, D-Minn., who shared the letter on Facebook and before her Senate colleagues last week.

Other families are also worried about paperwork delays, and the financial and medical effects a prolonged shutdown could cause.

Dania Palanker, a health policy researcher at Georgetown’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms, studies what happens when families face insurance difficulties. Now she’s also living it.

After arranging to reduce her work hours because of health problems, Palanker knew her family would not qualify for coverage through her university job. No problem, she thought, as she began the process in December of enrolling her family in coverage offered by her husband’s job with the federal government.

But there was a hitch.

“We could not get the paperwork in time to apply for special enrollment through the government and get it processed before the shutdown,” Palanker says.

Georgetown allowed her to boost her work hours this month to keep the family insured through January, but Georgetown’s share of her coverage will end in February.

Palanker’s treatments are expensive, so she is likely to hit or exceed her annual $2,000 deductible in January — then start over with another annual deductible once the family secures new health coverage.

“I’m postponing treatment in hopes that it is just a month and I’m back on the federal plan in February,” says Palanker, who has an autoimmune disease that causes nerve damage. “But I can’t postpone indefinitely, as my condition will get worse.”

Overseeing federal health benefits programs is within the purview of the Office of Personnel Management, whose data hub is operational, according to a spokeswoman. But getting information to that data hub to make the kind of changes Daskalakis, Palanker and others need depends on the individual agencies that employ government workers.

The OPM has told government agencies “that they should have [human resources] staff available during the lapse, specifically to process” such requests, which are called “qualifying life events,” the spokeswoman says.

In a written statement Wednesday, Smith said: “Oliver’s story is a powerful reminder that hundreds of thousands of real families have had their financial and personal lives turned upside down by this unnecessary shutdown.” The Minnesota senator called on the president to come back to the negotiating table.

For Daskalakis, there’s been some recent good news.

His union representative, Tony Walsh, says both the OPM website and Daskalakis’ insurer now indicate that the family’s request to change to an insurance plan that classifies the hospital as “in-network” will be retroactive to Oliver’s birthday — so the out-of-network charges may not play a role.

Just to be safe, “Joe is currently working on an insurance appeal based on no in-network care [being available],” Walsh reports in an emailed statement.

Still, the family has already received an initial $6,000 bill from the hospital, Walsh notes. He says that $6,000 does not include costs associated with Oliver’s birth or his stay in the intensive care unit — those charges likely are still to come.

Walsh says the shutdown is affecting a broad swath of employees in ways many lawmakers never anticipated.

The workers “are essential to the system,” he says, “and it’s unfair they are being treated this way.”

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service, is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation and not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Clinics Struggle To Resolve Fears Over Medicaid Sign-Ups And Green Cards

A migrant worker in a Connecticut apple orchard gets a medical checkup in 2017. A proposed rule by the Trump administration that would prohibit some immigrants who get Medicaid from working legally has already led to a lot of fear and reluctance to sign up for medical care, doctors say.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Last September, the Trump administration unveiled a controversial proposal — a policy that, if implemented, could jeopardize the legal status of many immigrants who sign up for some government-funded programs, including Medicaid.

The Trump proposal is still working its way through the public comment and evaluation process, and could go into effect as early as this year, though some state attorneys general say they would challenge any such policy in the courts.

In the meantime, some doctors and clinics are torn: They want to keep patients informed about the risks that may be coming, but don’t want to scare them into dropping health benefits or avoiding medical care right now.

“We are walking a fine line,” says Tara McCollum Plese, chief external affairs officer at the Arizona Alliance for Community Health Centers, which represents 176 clinics in the state. “Until there is confirmation this indeed is going to be the policy, we don’t want to add to the angst and the concern,” she says.

However, if immigrants do come to a clinic asking whether using Medicaid now might affect their legal status down the road, trained staff members are ready to answer their questions, McCollum Plese says. (According to legal specialists, the rule would not be retroactive — meaning it wouldn’t take into account a family’s past reliance on Medicaid.)

Other providers prefer to take steps that are more proactive to prepare their patients, in case the proposal is adopted. At Asian Health Services, a clinic group that serves Alameda County, Calif., staff members pass out fact sheets about the proposed changes, provide updates via a newsletter aimed at patients, and host workshops where anyone with questions can speak to legal experts in several Asian languages.

“We can’t just sit back and watch,” says CEO Sherry Hirota. “We allocate resources to this, because that’s part of our job as a community health center — to be there not only when they’re covered,” she says, “but to be there always” — even when that coverage is in jeopardy.

Currently, people are considered “public charges” if they rely on cash assistance (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or Supplemental Security Income) or need federal help paying for long-term care.

Trump’s proposed change to that rule, which is awaiting final action by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, would allow the federal government to consider immigrants’ use of an expanded list of public benefit programs, including Medicaid, food stamps and Section 8 housing as a reason to deny lawful permanent residency — also known as green card status. Medicaid is the state-federal health insurance program for low-income people.

If the proposed rule change goes into effect, it could force patients to choose between health care and their chance at a green card, McCollum Plese says. “And most people will probably not take the services.”

Already, some immigrant patients are skipping medical appointments out of fear stoked by the proposed rule, according to providers and advocates.

“For now, our focus has been on correcting misinformation, not necessarily raising awareness among those who haven’t heard about the potential changes,” says Erin Pak, CEO of KHEIR Center, a clinic group with three locations in Los Angeles. “This is a proposal that thrives on fear and misunderstanding,” she says, “so we wanted to be thoughtful about how and when to engage patients on the issue, given that nothing has passed into law.”

The Department of Homeland Security is reviewing more than 200,000 comments from the public before it issues a final rule. And it’s still possible the department won’t adopt the rule at all, legal experts say.

At KHEIR Center, most patients are immigrants from Korea. Many are highly aware of the proposed rule because of the coverage it has received in Korean-language media, according to Kirby Van Amburgh, the center’s director of external affairs.

Other groups served by the clinic, such as Latino and Bengali immigrants, have tended to ask few questions, Van Amburgh says.

Trained staff address patients’ questions one-on-one, she says, and hand out a fact sheet when needed.

Last month, L.A. Care health plan, which covers more than 2 million Medicaid enrollees in Los Angeles County, hosted a webinar on the topic for about 180 providers. David Kane, an attorney at Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles, led the webinar and urged doctors to tell concerned patients that nothing has changed yet — and that most immigrants would not be affected.

If the federal government adopts the rule, it would not be effective immediately, he notes; there would likely be a 60-day grace period before the changes take effect. After that, implementation could be further delayed or stopped in court.

John Baackes, CEO of L.A. Care, has been critical of the Trump administration’s proposal, and says his organization offered the webinar because of the estimated 170,000 clients — legal immigrants — who could potentially be affected.

“I think we’ve got to let people know what could come, and try to give them more accurate information so that they don’t act imprudently,” Baackes says. To do that, “we have to stay current.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.